Consider Apple's release of a new music-oriented device priced higher than its perceived competitors— which have already established an enthusiastic audience base over the past few years. How can it possibly survive in such a difficult position? The answer was: by being better in key ways that matter to users. iPod went on to become a legendary franchise in personal audio. Now Apple is doing the same thing again in home audio with HomePod.

This all happened before

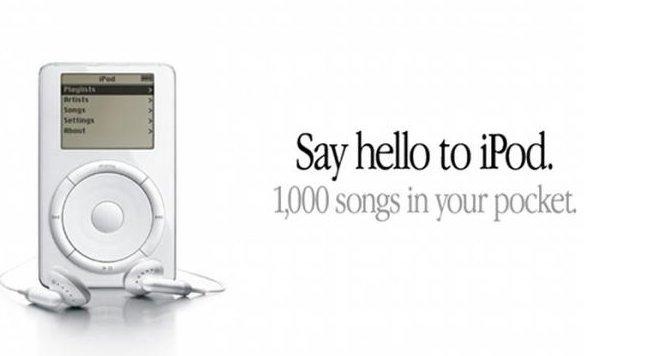

It's instructive to compare the current launch of HomePod with Apple's original mega-hit from 17 years ago: iPod. The first iPod wasn't actually that big of a seller. It took three years of sales before it accounted for over 90 percent of the market for hard-drive-based players.

From the start, however, it created a market and an ecosystem for a new kind of device that radically shifted the needle in personal audio players, unseating not just a new crop of MP3 players (from the "first" solid state MPMan player to the popular, mainstream Diamond Rio, and hard-drive-based MP3 players, including the Creative Nomad) but also derailing the 25-year-old incumbent Sony Walkman/Discman/MiniDisc franchise, and terminating the aspirations of the largest technology company of the day and all of its licensing partners: Microsoft's Windows Media Player initiative and later its Zune project.

Apple's iPod destroyed the big, entrenched mega corp; all of the small, nimble, independent innovators and the combined forces of all of the various global licensing partners of Microsoft at a time when the company itself was seen as beleaguered, a fledgling survivor of the Dotcom boom with no certain future — but facing major obstacles and entrenched competition from much larger rivals working in concert to kill it.

In 2001, at the iPod launch, Apple was barely making enough Macs (less than 1.4 million in the prior winter quarter) to matter, and those sales represented an annual decrease of more than 50 percent. It had just reported quarterly sell-through revenues of $1.6 billion, making Apple's entire business about as much of a commercially irrelevant niche as Microsoft's Surface operations today: whipped up, vocal fans who didn't buy enough of them to matter.

Critics portrayed Apple's new device as comically overpriced and missing important features. Slashdot, a once-influential web portal for nerds, famously dismissed the iPod announcement with the terse appraisal: "No wireless. Less space than a nomad. Lame."

How did iPod survive?

A 5 gigabyte iPod in 2001 was priced at $399. In 2018 dollars, that would be about $580 today, significantly more than the new $349 HomePod (which is wireless, and not only has far more local storage but can stream unlimited tracks from Apple Music and respond to voice commands).

Back in 2001, iPod wasn't just a relatively expensive new device; it was also priced far higher than its perceived rivals. According to the hive-mind chatting on Slashdot back in the day, alternative options included the MyDivaPlayer "offering a 128MB player that also accepts Flash memory for $135 after discount." The 6-gigabyte hard drive in the Creative Nomad Jukebox gave it more storage than Apple's iPod, and comments noted it "is like $250 MSRP (maybe $220 on the street)."

Another commented, "for half the price, you can get a smaller MP3 player and enough batteries and flash cards to keep most people happy, and which won't depend on the computer you use, and for the rest of the price you could get a low-end 3GB Digital Wallet [portable hard drive] for more storage. I can't offload my digital pictures to an iPod. I can't move files to any computer I want on an iPod. I can't use standard rechargeable batteries in an iPod. I can't find a reason to buy an iPod."

One person indicated he preferred to stick with 5-inch CD-ROMs. "$399 for 5GB? Screw that. I'd rather pay $100 for a Rio Volt. 700mb of songs per CD with an unlimited number of CDs, provided you change them."

It wasn't just cheapskate bargain buyers and techno-troglodytes who thought iPod was unnecessary and expensive. Once man commented, "I am both a shareholder and consumer of Apple products. When I read the announcement and specs I went straight to the Apple Store. At $199-$250, I would have bought two, immediately. Instead, at $399, I am buying zero, and expect that many other people will feel the same way."

In the end, it didn't matter that some people refused to buy an iPod. Those that did financed its continued development while enjoying a luxury product that made them happy. And those who saw how satisfied iPod-buyers were eventually lined up to buy one of their own.

Today isn't tomorrow

Despite all the logically-reasoned chat about why it couldn't possibly fool buyers into paying more for a better device that made them happier than the cheapest knockoff or a previous, clunkier version of technology, Apple's iPod found a base of enthusiastic users— even with its premium price nearly twice that of comparable MP3 players with more storage or solid state players with removable flash cards, and about four times as much as a basic, familiar CD-ROM player. Despite all the logically-reasoned chat about why it couldn't possibly fool buyers into paying more for a better device that made them happier than the cheapest knockoff or a previous, clunkier version of technology, Apple's iPod found a base of enthusiastic users— even with its premium price

Over the next several years, Apple continued to ramp up its iPod sales by offering more storage, faster transfers, broader compatibility and new features among those that skeptics were complaining about it lacking (including loading digital pictures and a disk mode for transferring files).

After crushing hard drive MP3 rivals, Apple launched a cheaper, lighter flash-based iPod nano and cleaned up in that market as well.

As years progressed, iPod dropped features that eventually grew irrelevant— including things like Firewire— which originally were key features. It also added car integration, video playback and workout-related features.

After iPhone appeared and shifted mobile electronics from basic media players to advanced computing devices, iPod was effectively turned into an app.

The concept of a portable assistant device also transformed into today's Apple Watch, and spawned new categories of wearables including Apple's addictive new AirPods.

Analysts line up to look foolish

As if they were literally born yesterday and can't read any archives of the internet offering a glimpse of how things have ever previously happened, thinkers of all kinds are offering their opinions on how a company that is now the largest and most successful maker and marketer of electronics on the planet — and which now has a global retail presence and massive, deep partnerships with every major retailer — won't be able to sell a new luxury home device priced so terribly high as the $350 HomePod.

As a frame of reference, HomePod is the price of a pair of Beats Studio3 headphones, about twice the price of AirPods, a third the price of an entry iPhone X and a bit less than an Apple Watch Series 3 with cellular (and significantly less expensive than a Link Bracelet or Hermes band, both of which are also sold in Apple Stores). It's also significantly less than the $500 Sonos PLAY:5, a wireless speaker that Apple already sells in its stores.

While analysts go nuts over the proprietary data Amazon collects on its buyers (giving it insight into what sells and what doesn't), none seem to appreciate how much insight Apple has on the buyers who fill its hundreds of stores globally, all making luxury purchases (rather just than shopping for bargains online). Perhaps Apple does know what premium buyers want, given that it has been selling them its own and third-party headphones, wireless speakers and home automation products for years.

Somebody tell CNBC, who trotted out BK Asset Management's Boris Schlossberg (never heard of him, just saying) to opine on Apple and HomePod: "I do think they're in trouble. I think they're making a huge mistake. They're basically betting on the fact that high expensive products can be sold at this point and it's clearly becoming evident that everybody has caught up to them in the marketplace."

I had to point out that these comments were specific to HomePod, and not made about iPods back in 2001, or iPhone back in 2007 (when Microsoft's CEO laughed at its price), or Apple Watch in 2014— years after the marketplace had 'established' that few people were willing to pay even $200 for an Android Wear or Samsung Gear smartwatch.

I should also point out that one reason I've never heard of Schlossberg is because he's not a technology or consumer products expert. He's billed as a foreign currency exchange expert. Yet he's talking about a home speaker and Apple's ability to sell luxury technology products, thanks to CNBC, which tied Schlossberg's comments in with the idea that iPhone X orders are being slashed due to weak demand.

Calling HomePod a smart speaker is like calling iPod an MP3 player

What was it that enabled Apple to sell an "MP3 player" for two to four times the price of other devices that could also play back lots of albums? Critics like to vilify Apple for using an attractive design, branding and marketing to sell products at a premium, as if this is a bad thing, like castigating the FBI for investigating. But there's more to it than Apple's showmanship.

If iPod's success were just the result of ads and fluff, why have Microsoft's billions of dollars invested in advertising and fluffing PlaysForSure, Windows Media, Zune, KIN, Windows Phone, Microsoft Band and Surface all such pointless, inconsequential disasters? After all, it was Microsoft that for years led the bullied demonization of Apple's "cute, luxury branding" before desperately seeking to copy it, without actually being able to.

A primary component of iPod's success was its attachment to Apple's ecosystem. Originally, iPod was a peripheral "pod" to the Mac, where users could organize their music and other media in iTunes. Apple's modern iOS devices have since become their own digital hub, with peripheral "pods" connecting to Apple Watch, AirPods, HomeKit, Bluetooth devices and via Continuity.

HomePod fits into that current ecosystem, allowing users to not just stream music from their iPhone or Mac, but to directly request playlists and songs from Apple Music using their voice. It also serves as a HomeKit hub, orchestrating lights, blinds, door locks and other home automation devices. This increasingly tight-knit integration offers a real challenge to other proprietary alternatives to AirPlay (including Sonos and Google Cast).

Apple doesn't need to kill off Sonos or Google or Amazon Fire sticks or all other wireless speakers to establish a solid business in high-end, easy-to-use and affordable home audio products. It sure didn't need to stop all sales of rivals' super cheap MP3 sticks and clunky hard drive players back in the days of iPod to establish global leadership in music players.

And similarly, Apple doesn't need to beat down, scuttle or race to duplicate the partnerships Amazon and Google are desperately trying to establish to enable home users to order an Uber, start their washing machine, turn on the shower, ask for a not-funny joke or formulate some difficultly parsed, general knowledge question using Alexa or Assistant. Apple also didn't need to copy Microsoft's licensing deals in Windows Media PMPs to get all of the world's consumer electronics firms to support it with iPods.

And Apple also doesn't need to release a $30 "Dot" version of HomePod that only listens for Siri, because it already has 500 million active devices using Siri— they're not in a kitchen being asked for jokes; they are already in CarPlay cars, on Apple Watch wrists, in AirPod ears and in the pocket of virtually all affluent users of smartphones, listening for simple things that a voice assistant can actually do quite reliably: take a note, skip a song, get directions and launch an app.Amazon and Google are desperately seeking to build a voice-platform that can rival the smartphone for attention. Apple already has the smartphone platform, and it already has voice integration

Amazon and Google are desperately seeking to build a voice-platform that can rival the smartphone for attention. Apple already has the smartphone platform, and it already has voice integration.

One can shout from the rooftops that Alexa and Assistant might occasionally be able to do things Siri can't, but the obvious answer is that Apple Maps has plenty of grievous shortcomings but it's still the most used mapping app on iOS, the platform that matters— despite valiant efforts by Google to make its own maps app better in key ways.

And more importantly, when an iOS user uses Google Maps or Amazon's Alexa service, it doesn't hurt Apple in the slightest. Instead, it reaffirms that iOS is the mobile platform that matters. As the market buys into Apple's ecosystems, HomePod will have the same ability to adapt and change to fill new roles just as iPod evolved across its lifespan, launching new product categories and services along the way.

On top, as anyone who uses them knows, Alexa and Assistant are not actually as genius and flawless as their anti-Siri cheerleaders make them out to be, as spoofed in a popular viral video.

HomePod is product. Alexa & Assistant are surveillance services.

But perhaps the primary reason why HomePod will attract a valuable base of buyers is that Apple makes products to delight its users. That's how Apple makes virtually all of its money. It doesn't sell ad placement by offering advertisers insight into when, where and how certain users will be most vulnerable to their messages. It doesn't line up sellers with the tools to extort higher prices from buyers by shifting prices around at different times or to different demographics. HomePod is being sold to buyers straightforwardly as a great audio product, just as iPod was 17 years ago

HomePod is being sold to buyers straightforwardly as a great audio product, just as iPod was 17 years ago. Amazon Alexa (across all of the devices it's sold with) is not a product sold to users to benefit them. It is a service provided to users nearly at cost in order to herd them toward other sales and take advantage of all of the information it can collect on how they shop, what they do and what, when and how they do it.

Google's Assistant is just a knockoff of Alexa. If anyone "missed the boat" on voice assistants, it's not Apple (which brought Siri into the mainstream as Google and Microsoft publicly denigrated the idea of voice assistants on a smartphone). It's Google, the company that boasts of 'organizing all of the world's information' for paid placement of ads, which sat there while an online warehouse company beat it at installing an intelligent tracking cookie in the homes of its customers.

In the real world, Google is an ineffective, bungling giant corporation with a toxic culture that is sitting on a monopoly of intellectual property that funnels it money regardless of how badly it actually performs in new initiatives, from tablets to robots to watches. Just like Blackberry, Nokia and Qualcomm. You don't need to be a technology historian to know how that will turn out.

Or alternatively, the greatest boat-misser is Microsoft, which had a vast installed base of PC users that it failed to convert into a monetized source of tracked, surveilled ad sheep with its own belated Alexa-ripoff, Cortana. We don't even need to consider the whole missed boat regarding mobile devices to point out what a huge failure Microsoft's voice surveillance efforts have been just on the Windows PC.

But no, let pretend it's Apple that "in trouble" because it supposedly can't sell premium products in a market saturated for years in cheap alternatives, when that's the only thing Apple has done for 40 years.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

79 Comments

It really is true. I owned a Sony mini-disc player, a Rio MP3 player, AND the CD-player sized Nomad prior to buying the original iPod. Once I used the iPod, those other products quickly became irrelevant. It also helped that I had been using Soundjam for MP3 rips and that's what Apple acquired as the initial basis for iTunes software.

I only buy Apple designed products...if Apple doesn't make it, I prefer to do without. (TV, printers being the notable exceptions.)

I refuse to buy "Costco-esque" junkie, clunky, 'plastic' devices.

I"ve passed on the whole Home automation scene, much like I passed on MP3 players until the iPod Shuffle came out.

Good article. I love the history Daniel brings to the table! :)

I do ask myself the question “why now?”

With iPod it was an opportunity given by the small form factor hard drive that let them build a box the size of a packet of playing cards that could hold 1,000 songs (and more, in my experience)

What has HomePod got stashed away in there, hardware or software, that was previously not possible? Apple’s last attempt at innovative speaker technology- the Apple HiFi- was clever but did not become a hit.

Counterpoint: