Every year, complaints come from the usual suspects demanding to know when Apple will innovate, and specifically when it will launch a new, even more popular form factor than iPhone. Does "innovation" require iPhone to fail as a product?

Based on criticism, it might seem that for Apple to "innovate," it must get rid of smartphones and deliver some new, arbitrarily different product to take the place of iPhone. But Apple isn't competing against iPhone.

Apple is competing against the status quo that exists outside of Apple.

Apple's successful innovation on display

To innovate literally means "make changes in something established, especially in introducing new methods, ideas, or products." You'd have to be really intellectually lazy to think Apple isn't doing that.

In fact, reviewing the history of consumer technology, Apple has introduced the most profound changes in new methods for personal computing— with bold and often radically challenging new ideas — and its products have been some of the most exciting examples of fresh new takes that rival tired-out efforts by the established tech industry players surrounding it.

The results of its innovation are apparent in the market, where Apple creates and dominates demand for high-end notebooks, phones, tablets, watches, and— with AirPlay 2, HomeKit, HealthKit, and CarPlay — even broadly across premium home entertainment, home and health-related devices, and in the automotive space as a user interface.

The initial spark of Apple's innovation (1970-1990)

At its start in the 1970s, Apple was a conventional computer maker, differing mostly in the sense of selling more expensive gear that was often better built (outside of the ill-fated Apple III that was rushed to market).

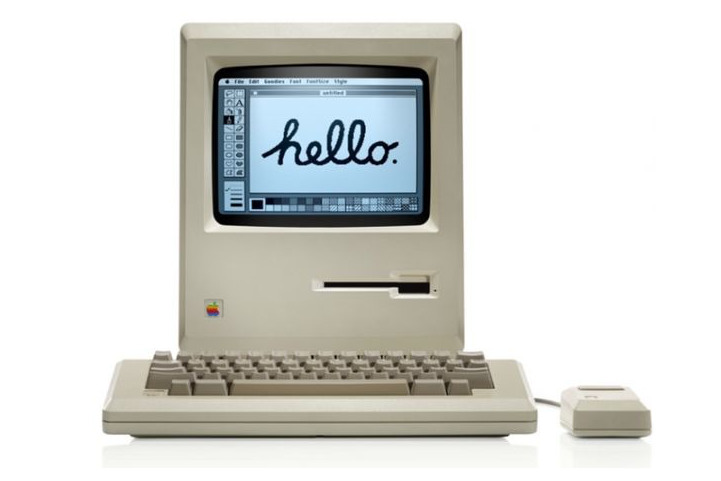

But Apple's biggest differentiator was the Mac, and its biggest innovation was applying research at PARC (the Palo Alto Research Center created by copy-machine maker Xerox) to revolutionize personal computing.

Xerox was afraid of introducing new graphical computing systems that might threaten its lucrative cash cow copiers, which required lots of billable time and effort to support and maintain. An easy-to-use computer system that dealt with virtual documents rather than physical papers would be the death of copy machine empires. In fact, it certainly was.

Today, emails even commonly request that you don't waste resources by printing them out on paper. Copiers still exist, but aren't the center of office life; computers are. Xerox is barely around as a brand anymore.

Apple entered into a partnership with Xerox to take a look at the new technology the copier firm didn't quite know what to do with; after a million-dollar investment from Xerox, Apple undertook the effort to adapt Xerox's windows of an on-screen, graphical user interface, driven by a mouse, as Lisa and then Macintosh.

Lisa was a first attempt to make use of existing technology to deliver a relatively high-resolution, dot-matrix display with enough storage and memory to work with virtual documents in the computing space. By the time it was released in 1983, its technology was still too expensive to catch on outside of a few shared machines inside major companies.

What was catching on was IBM's new DOS PC of the same era, which was cheap enough to put under everyone's desk, and even for many people to have at home.

Innovating unlike the industry

Like Xerox, IBM was also afraid of innovating too far with the PC and challenging its own bread and butter: bigger office minicomputers that again required large support staffs to set up and keep running. Unlike both of them, Apple was keen to ditch its entire existing lineup of Apple II's and deliver an entirely new generation of personal computing.

That explains why Apple went out and found a much more powerful processor in Motorola's 32-bit architecture 68000, while IBM purposely sourced a cheaper and more limited Intel 8088 — certainly not the best processor for the job, even from Intel. Just like Xerox, IBM was afraid to really innovate and end up with a smaller business empire.

As the Lisa's high price struggled to woo enough buyers, Apple was actually fostering internal, innovative competition with another project: a less expansive but still relatively powerful Macintosh, aimed at taking the place of the simpler but ubiquitous PC as well as the Apple II line.

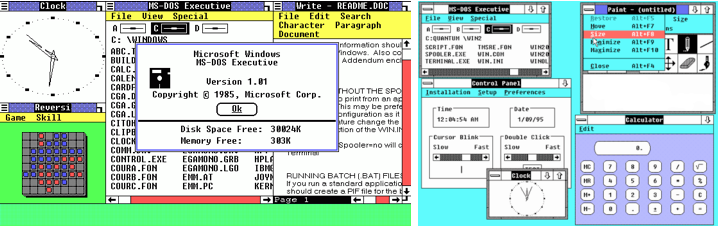

Like its partner IBM, Microsoft was also worried about something that might dethrone the lucrative empire tax it had managed to establish on PCs by licensing its proprietary MS-DOS software to IBM. While rushed to market "first" to beat Apple's release of the internal development of Macintosh (as Microsoft was developing software for it), nobody seriously used Windows 1 or 2 because they were not any better than MS-DOS.

Unlike Lisa and Mac, Microsoft's first stab at Windows couldn't even support overlapping windows.

Years after it embarked on its own initial efforts to copy the Macintosh, Microsoft didn't widely deploy Windows until Apple's Macintosh graphical UI had established a clear advantage over text-based computing. Windows wasn't bundled on new PCs until its third version in 1990.

A second spark of Apple's innovation (1990-2000)

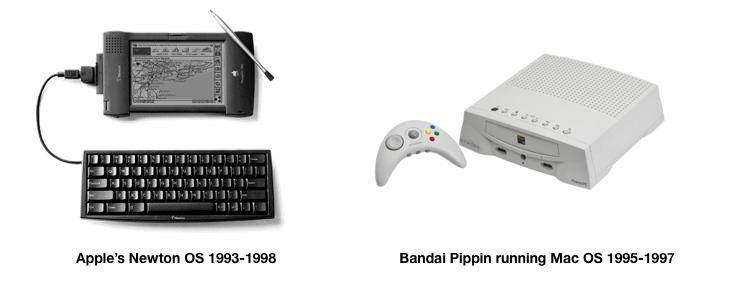

Apple of the 1990s is perhaps most famous for its unsuccessful effort to launch the Newton MessagePad, an ambitious effort to deliver "pen computing" on a small tablet device. Like Lisa, this effort turned out to be "too new" in both its hardware and software and also too expensive to justify significant sales.

Apple also tried to license the Mac the way critics had long demanded, which also ended up disastrously.

As with the Mac, Apple went shopping for a powerful new CPU that could drive Newton and — after failing to find anything good enough — ended up working with desktop chip maker ARM to deliver a new mobile chip. That new chip architecture grew to great success and is now the world's most successful globally, driving virtually everything outside of legacy WinTel PCs.

While Apple teetered on failure in the late '90s, Steve Jobs was able to sell Apple's joint stake in ARM for over a billion dollars and rescue his company in the way that wags like to pretend Microsoft's $150 million investment somehow did.

But Apple's big success of the '90s wasn't some entirely new form factor that boldly invented some vastly different product category. Nor was it the ill-fated Mac licensing that pundits lauded as precisely what would save Apple because Microsoft had already demonstrated it worked.

The very same kind of critics who castigate Apple's every move today were also doing it back then when they imagined that innovation was just doing what everyone else was doing— the opposite of innovation! They didn't get it then and they still don't get it.

Innovation takes the Mac mobile

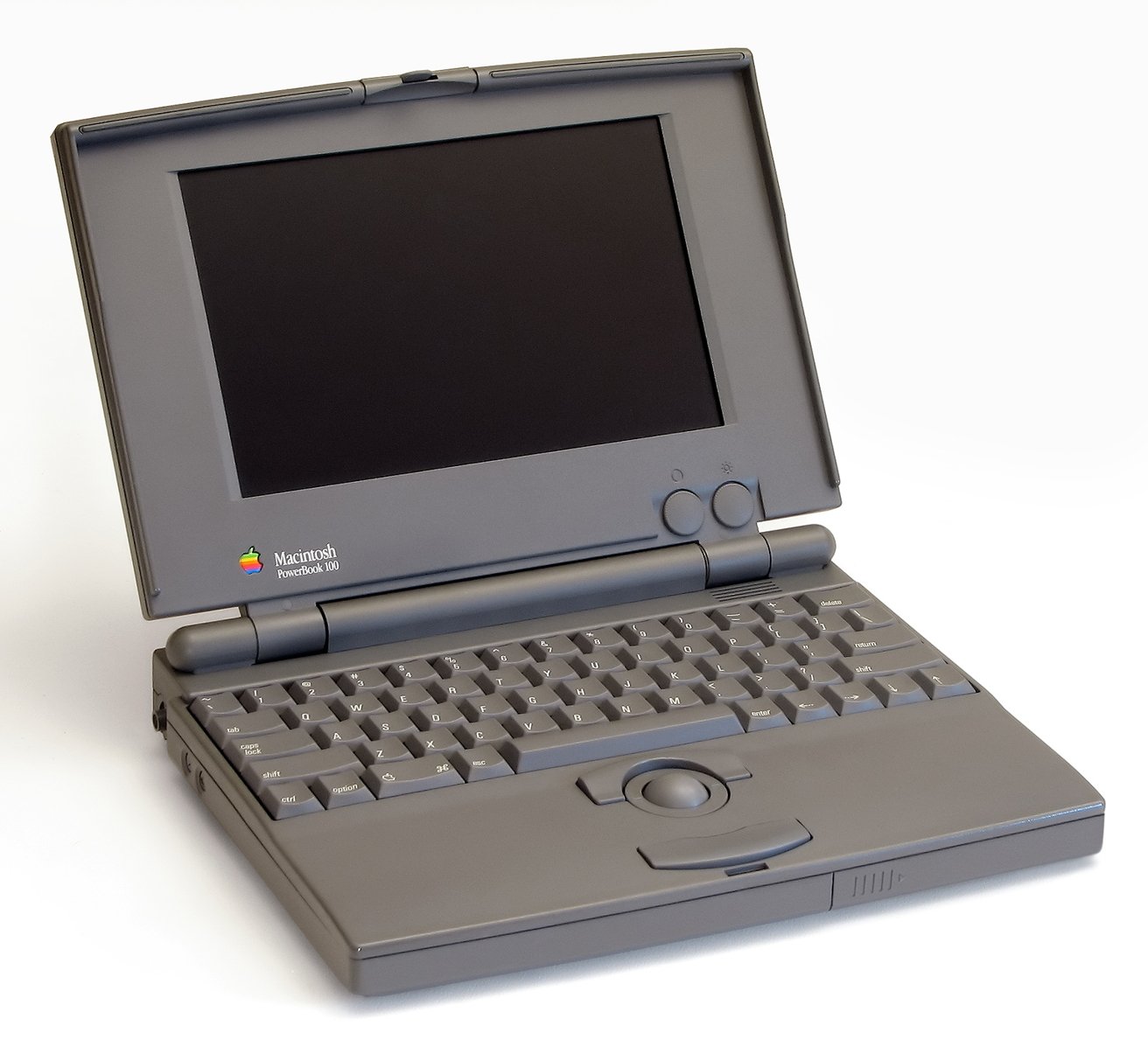

Apple's big success of the '90s was actually an incremental advancement of the Macintosh. It was the PowerBook.

Leading up to the PowerBook's 1991 introduction, Apple decided its "luggable" Mac Portable wasn't enough to bring the Macintosh into the rapidly expanding market for notebooks. The company's internal Apple Industrial Design Group initially began working with Sony to miniaturize the components and design of the Mac to fit in a notebook.

But Apple also didn't just make a conventional PC notebook running Mac software. PC laptops of the day were oriented around text-based DOS software and applications. Because Apple's PowerBook would run the Mac's pointer-oriented, graphical UI, Apple relocated the trackball — effectively an upside-down mouse — front and center, leaving palm rests on the front edge and pushing the keyboard back towards the screen.

Like the Mac's UI itself, the result was controversial at first, but after catching on, it eventually became the layout with which virtually all notebooks were designed, even today, over 30 years later. If you get it right the first time, you don't have to blindly make new, arbitrary changes just to change things around.

Innovation should be driven by improvement, not pure novelty.

Apple had dutifully made regular changes to the Mac and PowerBook to use new technologies, from better screens to better mice, even replacing them with the superior trackpad. Apple also went shopping for chips again and this time settled on a new 64-bit architecture jointly created by Apple, IBM, and Motorola: PowerPC, used in new Macs starting in 1994.

Yet at Steve Jobs' return with the 1996 acquisition of his NeXT Computer, the Old Apple wasn't innovating on all cylinders, and its market results reflected that. Consumers were flocking to the Windows PCs and notebooks, which weren't really innovating as different or better but were cheaper. Newton was floundering as the cheaper, simpler Palm Pilot gained traction.

A third spark of Apple's innovation (2000-2010)

Jobs surveyed the market to identify where it could innovate into a new space. There were many potential options, some of which the Old Apple had already tried to muscle into. That included laser and inkjet printers, CD-ROM players, and digital cameras — which Apple brought to market with Kodak but couldn't dramatically usher into the mainstream because like Newton, they were too new to be practical.

Apple had been unsuccessfully trying in so many areas that Jobs went on a slashing spree to rid it of all this deadwood. He even pared back the Mac and PowerBook lines into a much tighter array of products. Sometimes the most innovative thing you can do is say no and focus on what you're good at.

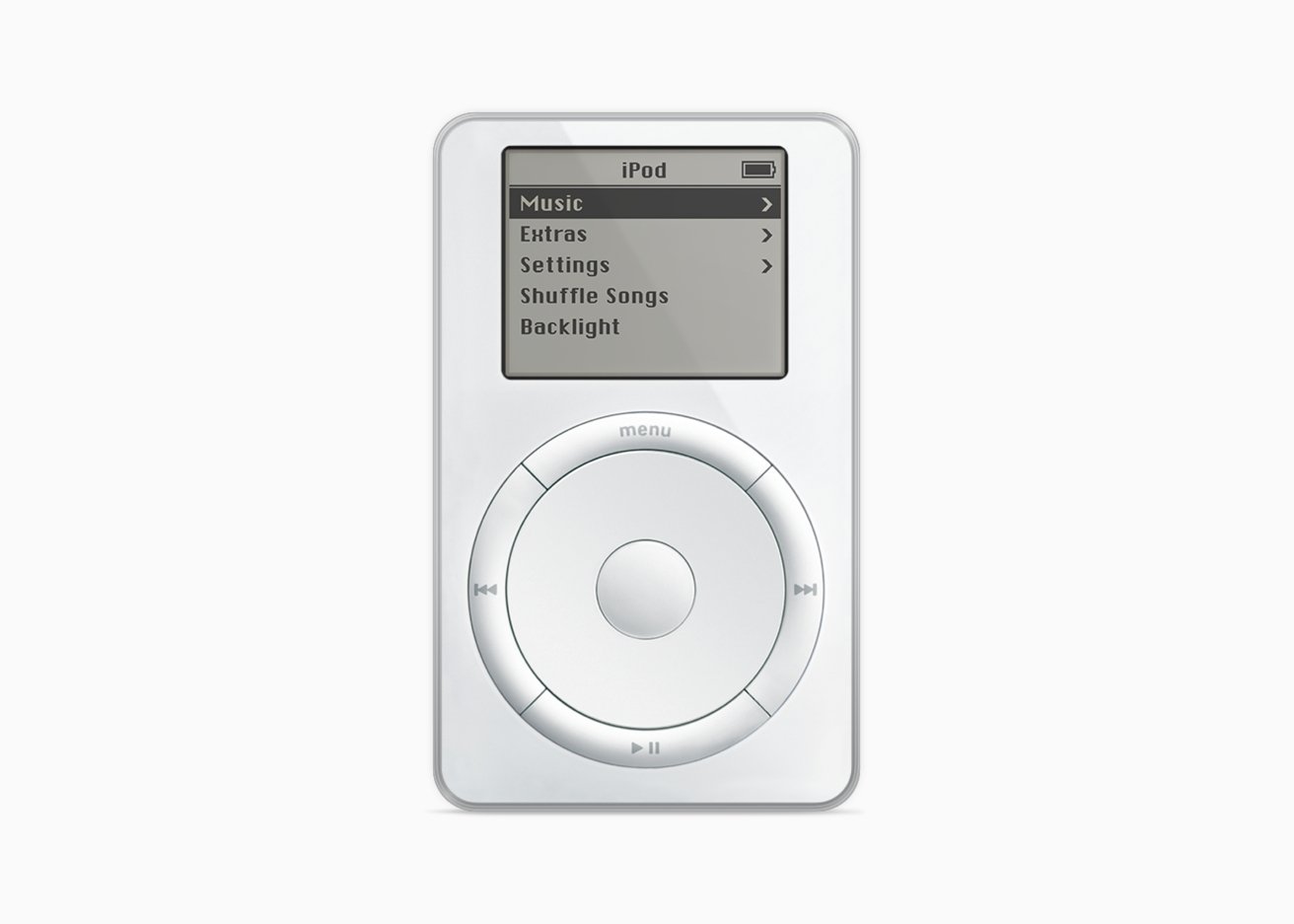

But Jobs also delivered a new hit with the iPod. MP3 players, unlike cameras and disc players, were not dominated by established players that would be hard to unseat.

They were largely experimental, somewhat impractical, and ripe for the same kind of innovation Apple had excelled at before with the Mac: a great dot-matrix UI that could display anything.

Jobs' Apple again went shopping for powerful mobile chips and found the best one was the ARM chip it had started work on a decade prior. As with Sony and the PowerBook, Apple largely licensed the handheld internals and focused on adding what it was good at: a dot-matrix display and very usable controls.

A keyboard wouldn't fit and wasn't necessary. Instead, Apple adapted the trackpad into a circular selector and button that could be used to spin through an efficient set of menus to play hundreds of songs, instantly from a hard drive.

Many reviewers famously hated it and its price. The market responded by rapidly making Apple a profitable company and setting it up to launch its next major spark of the decade with the iPhone.

Apple's successive generations of iPod became more and more powerful until they were offering to handle your calendar, contacts, notes, and even play videos and simple games. The industry and its pundits broadly imagined — or perhaps dreamed — that MP3-playing smartphones would arrive and derail Apple's iPod by doubling as an MP3 player.

There was much salivating and a loud smacking of lips that Apple's iPod success was destined to dry up and blow away.

Apple again does the opposite of the industry

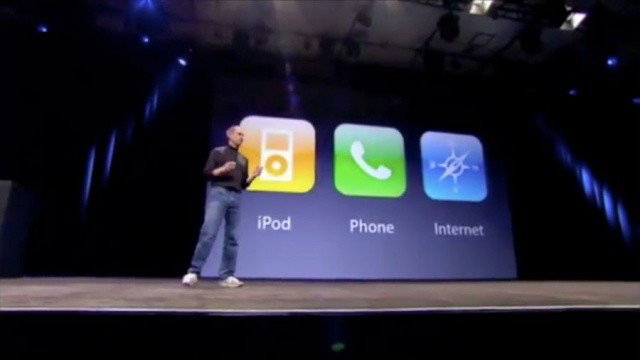

Instead, Apple went to work to innovate beyond the iPod. Rather than just adding a phone, Apple instead borrowed the computing platform of the Macintosh to deliver a mobile computing device that could also act as a phone and an MP3 player.

Jobs didn't call it a mobile Mac. Instead, he focused on its three strongest features at the iPhone's introduction.

"Today we're introducing three revolutionary products of this class. The first one is a widescreen iPod with touch controls. The second is a revolutionary mobile phone. And the third is a breakthrough Internet communications device.So, three things: a widescreen iPod with touch controls; a revolutionary mobile phone; and a breakthrough Internet communications device. An iPod, a phone, and an Internet communicator. An iPod, a phone... are you getting it? These are not three separate devices, this is one device, and we are calling it iPhone."

Apple's 'three-in-one solution' wasn't afraid to cannibalize the iPod; it aimed to! In fact, while Apple continued to offer iPods for some time in the wearable space, it also delivered a version of iPhone without the phone, called iPod touch. It boldly migrated the entire iPod into the very platform that would replace its existing MP3 system.

While the new iOS platform of iPhone was gobbling up the conventional iPod, Apple was also preparing to radically reinvent the Macintosh. It didn't need to replace the Mac, but it did need to equip it for the future.

Outside of the Mac, the PC industry only imagined cheaper products. PCs and notebooks were all getting cheaper, flimsier, and less powerful as the bloat of new iterations of Windows taxed them to death. The answer to many was Netbooks, a dirt-cheap soft-of-notebook scaled down with a bargain-basement price. Perhaps it wouldn't even run Windows!

Microsoft was clearly afraid of a future PC form factor that failed to pay a Windows tax, so just as it had done with its pen-computing concepts, its Palm Pilot concepts, its SPOT watch concepts, and its smartphone concepts, it also delivered "ultra-portable" concepts wedded to a slimmer variant of software branded as "Windows."

Bill Gates failed to deliver innovation in most of the categories where Microsoft tried

Bill Gates failed to deliver innovation in most of the categories where Microsoft triedYet outside of the conventional PC market, Microsoft Windows wasn't making serious headway in slates, PDAs, watches, tablets, or netbooks, and its market results reflected that.

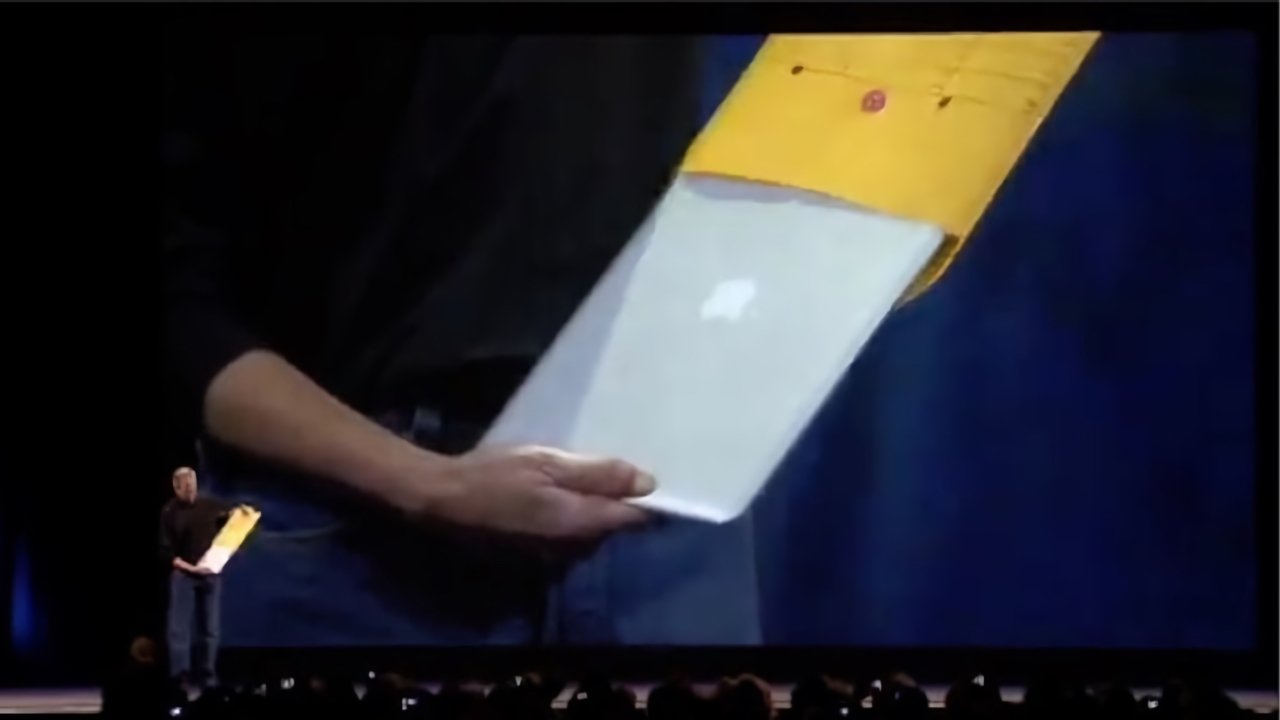

When PCs went cheap, Apple went premium

Rather than making a Mac netbook, as so many wanted, Apple looked at the MacBook (the new name PowerBook got when Apple went shopping for a better alternative to PowerPC chips and settled on Intel's x86 for Macs and MacBooks) and decided to fundamentally revolutionize and upgrade the physical, core architecture of its platform by ushering in the future.

The 2008 MacBook Air unveiled a new architecture that could make use of new "methods, ideas, and products." That included Apple's new Unibody construction for building a slim new case with unparalleled strength and rigidity.

It also included the innovation of moving the Mac to solid-state drives. In the last article, I erred in stating that MacBook Air only used SSD. As a commenter correctly noted, it was initially offered with a spinning disk as a cheaper option.

Yet the MacBook Air did indeed introduce SSD before it was broadly affordable, demonstrating the clear advantage of an emerging new technology that could instantly launch apps and open documents, and could last longer and handle aging more gracefully than a failing mechanical hard disk. Like many other innovations, SSD was initially prohibitively expensive for consumers before it became commonplace; that occurred because Apple saw the potential past the price.

The MacBook Air also debuted new controversy by encasing the memory, drive, and battery and gluing them inside in a way that wasn't user-serviceable. Apple's goal was to deliver lighter and thinner devices that didn't require space for latching mechanisms and didn't invite users to pull out drives and memory and replace them with something cheap that might fail, as was a common problem.

Selling MacBooks as sealed products delivered innovation that made products better, more reliable, and simpler, at the cost of riling up critics who didn't want anything to ever change, and confused their cheap neanderthalism with innovation.

While PC and even Linux netbooks appeared to be successful for a hot minute — or perhaps 15 minutes — they aren't really around today. What is around today are copies of the MacBook Air, which virtually every PC notebook looks exactly like. Most of these also now use SSDs and Unibody-like construction.

A fourth spark of Apple's innovation (2010-2020)

Jobs' last major impact at Apple was iPad, the 2010 device that quickly crushed netbooks and rendered them pointless. If you're going to accept limitations for being cheap, why not get a nice device that isn't just flimsy e-waste? The market agreed.

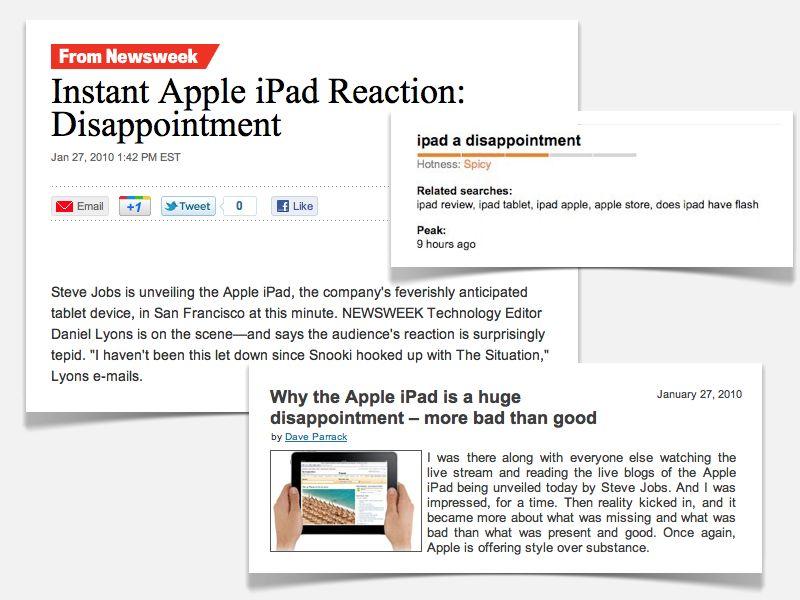

While critics eventually recognized iPad to be a worthy new "innovation" from Apple, at its debut there was controversy inside and outside the Apple flock, where many expected the tablet to be a pen-based Mac. Instead, it was a "big iPod touch," or you might say, an iPhone without the cellular phone, in a larger size. After its initial introduction, Jobs reported feeling annoyed and depressed at the disparaging hostility critics flung at it.

Apple actually created its iPad prototype first, in an effort to deliver the concept of a highly mobile, one-piece, wirelessly connected display that delegated some of its computing utility to the cloud. Yet selling such a device would be Newton-style difficult because nobody really knew they needed it yet.

So Apple's real innovation here was to add a cellular phone to its iPad prototype and shrink it down to be usable as a mobile phone. Many could see some benefit to having a smartphone, if only they were easier to use. Cellular providers were also able to subsidize the price of an amazing, data-hungry handset more than the price of a potentially-successful tablet.

So when critics only count Mac, iPod, iPhone, iPad, and maybe Apple Watch as The Innovations and ignore Apple's more blockbuster shifts of the industry— things like UI, construction, silicon, OS, controllers, and components— it gives away that they don't know what they're talking about. Throughout the 2010s in particular, they certainly didn't.

Apple makes smart watches popular

And speaking of Apple Watch, which debuted under Cook in 2015, it too was like iPhone in the sense that it replaced an existing iPod. Apple actually pulled its wrist-wearable 6G iPod nano off the market and revamped it into being an iOS-based, purpose-designed, fashionable new product category with an entirely new input system based on the Digital Crown, again with a dot-matrix display.

And yet, despite all of its newness, critics like to disparage Apple Watch as not really a big deal because it didn't replace iPhone as a communicator. Apple would have to be monumentally stupid to hope to displace iPhone, nearly as foolish as the critics who outright demanded it.

Recall that also in 2015, the Wall Street Journal insisted that Apple also get rid of the entire Macintosh line and focus on iOS-based devices. Wow, it is spectacularly and profoundly inept to think Apple should dump entire massive categories of its business for no good reason, just to look 'innovative' to people who can't grasp the concept.

Apple did discontinue iPods, but only after delivering the more capable iPhone, iPad, and Apple Watch lines, all of which can also play MP3s and videos, making them better iPods than iPod. But Apple had no need to discontinue the Mac after launching iOS because the macOS does things iOS doesn't attempt in order to be ultra-mobile.

Apple has also launched other products and initiatives that take iOS in new directions. HomePod in 2017 basically created an iPod for your house using iOS, and replacing a controller with your voice; it only has one simple button and no real dot matrix display for perusing menus or any sort of complex, graphical UI.

While it's hard to compare HomePod to Apple's big hits, the problem isn't the product; it's that there isn't a similar potential demand for home iPods or even a home iPad. Nobody else who tried to sell voice first home devices has delivered any sort of commercial hit, unless you count Amazon and Google giving away devices as commercial activity.

Stationary Voice First tablets for the home are even less popular, indicating— just like curved smartphones and 3D TVs— that there isn't always a huge demand for a product category when you invent something "new," just because.

And the reason why Apple's premium innovations are so much more successful than rival smartphones, tablets, and watches is that Apple built its products to be better than the status quo, not just reach a minimum viable product.

Measuring Apple's innovative success against iPhone's popularity is deceptive because there is naturally a larger market for a handheld smartphone (who are we kidding, it's a computer-camera that can text) than there is for just an MP3 player, or for a large tablet that doesn't need replacing every year or two, or a desktop or laptop Mac, which also lasts longer than an iPhone.

Apple could also make gimmicky folding phones (Why? To show off displays it doesn't desperately need to sell?), or PCs that turn into tablets (Why? To sell fewer units and earn less?), or even smart-toaster-refrigerators (Why? To attempt selling a distracting array of products nobody needs?) but it's concentrating on delivering the best new products it can, and for which have some clear, potential use that will justify their development.

A long history of rarely appreciated innovation

Having reviewed Apple's biggest sparks of innovation over the past forty years, leading up to today's Vision Pro as tomorrow, today, it becomes clear that Apple isn't merely innovating in new product categories' with new marketing names.

Depending on how you look at things, Macs and MacBooks could be "one innovation," when they now encompass several product categories and markets all named Mac. Is that a lack of innovation? Apple's Macs are and have been at the forefront of innovative thinking so bold it has frequently risked controversy and often raised the ire of critics.

But you could also say Apple's entire iOS, iPadOS, watchOS, and homeOS are also really just optimized variants of the macOS they descended from, and therefore all of its product categories are really Macs under different names. Certainly, that doesn't make them examples of a "lack of product category innovation."

Even different iPads in Apple's range serve broadly different purposes and audiences! They wouldn't be more innovative under widely different marketing brands. Apple was at its least innovative period back when it had the most sub-brands and product categories!

And just because iPhone, Apple Watch, and HomePod eventually replaced iPods as a product category, doesn't mean Apple's other product categories have to be replaced to deliver "innovation." Certainly not the cash cow iPhone!

A better understanding of the often invisible work Apple has done with its user interfaces, its OS platforms, its silicon chipsets, its graphics, its Neural Engine, and its physical hardware gives you a deeper appreciation of the real innovation Apple has achieved, even as the overall industry has clung to legacy and desperately tried to preserve it to avoid the expense of innovating and the potential opportunity cost of delivering new, real innovation that threatens its existing status quo.

I'll work to deliver a closer look at examples of these in upcoming weeks.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Bon Adamson

Bon Adamson

-m.jpg)

24 Comments

Tim Cook can’t lead Apple to produce innovative products because he’s an operations guy. He knows how to sell price points tied to feature sets, not innovative products. That’s why we have two sets of AirPods 4. We only need one, we should only have one, and all of the innovative features of AirPods could have been boiled down into one strong, focused product…But we have two, because Tim couldn’t make AirPods 4 and AirPods 4 Pro because there‘a already AirPods Pro and that would be too confusing, so he split them into AirPods 4 and AirPods 4 with Active Noise Cancellation. Y’know, because Active Noise Cancellation is a feature tied to a higher price point so Apple has to remove it for one set of AirPods to get you to spend more money…again, Tim likes price points tied to features, not products.

Innovation at Apple is dead so long as Tim Cook is the CEO.

…You can even look to the Apple silicon transition. We finally had an opportunity to give all the devices new powerful chips and drive down the cost of products by keeping everything in house. Yet, after M1, Tim leveraged the new chips to make every single product line more expensive. So expensive in fact, that they can introduce new products like the MacBook Air 15 inch that replaced the price point of the MacBook Pro 15 inch…because that’s now a 16 inch MacBook Pro and is over $1000 more expensive. Remember when the MacBook Pros got a $500 price increase because of the Touch Bar, and then they killed the Touch Bar and the product prices remained the same?

I love these deep dives into Apple and the history of computing. I've been a big fan for decades and have read every new article Daniel publishes with focused intensity. Highly recommend!

Today's Apple still swings big, but Tim Cook doesn't use the products the way Jobs did. Jobs was a perfectionist who had no problem calling out problems with Apple products that weren't good enough for him, by either demanding a re-design or killing the bad ones outright. Project Titan (Apple Car) is a great example. It needed to be killed sooner, or better focused so that something resulted from that massive investment. It's not like there isn't room for innovation in the automobile industry. Since DED referenced it early in the article, HomeKit is a great example. Why is it so darned bad? The interface is very un-Apple. Non-standard, glitchy and non-intuitive. Products like the HomePod sound good if you can get them to work, but connecting them is a pain. Even the AppleTV interface is still really clunky and frustrating. Steve would be so pissed that this stuff, which has potential but isn't ready for prime time, has the Apple name on it. It's now looking like Tim's big gamble on turning Apple into a movie studio is being scaled back. In this case, the content is often very good, but I don't think Tim realized how brutally expensive it can be, especially when a big investment is a flop (See and Foundation are two good examples). So, to get back to the thesis DED proposes, yes, it is easy to get complacent when the cash is rolling in. That's why it took Apple so long to react to the emergence of streaming when they were focused on iTunes downloads. Having billions means you can sometimes buy your way out of a mistake, but I still shake my head at the cost of buying Beats and paying off Dr Dre and Jimmy Iovine. Apple is still a distant second to Spotify and may never catch them. The Vision Pro is another example of a product that should not have been released. So yes, keep innovating, but let the ideas come from your talented teams, not the top. Tim's a great manager, not not a vision guy. I will give Apple props on the M-series chips. Who could have imagined that Apple could make better chips than Intel? But the products aren't exciting the way they once were, and the design of things like the new macOS system preferences pane is a great example of how mediocrity is tolerated. I'm sure there are more Tony Fadels and Scott Forstalls in the lower ranks at Apple. Let them do the innovating. Not the top brass. Tim needs a deputy who will demand perfection and promote innovation while he sees to the business side.

This article author has failed to grasp technology innovation from the big picture perspective.

It can explain it in ONE sentence: consumer technology innovation is driven by the smartphone, the primary computing modality of consumers today.

Unfortunately this is so typical of many technologists: they can't see the forest for the trees. All of the major tech innovations we see in our lives today stem from the ubiquity of the smartphone. Wireless communications (cellular, WiFi, Bluetooth, RFID), NFC contactless payment, advanced cameras, biometric identification, display panel improvements, battery technology, and machine learning/AI. All the wearables and accessory devices are rooted in smartphone innovations. That's just the tip of the iceberg.

To look at the computer sitting on your desk as the focal point of the discussion of consumer technology is antiquated. It has been for over a decade.

This excessively long winded article is full of cute little snippets of computing history which shows he clearly doesn't grasp the fundamental nature of where innovation is happening today.

If I had to pick one specific moment and/or device that Apple invented (after the iPhone) that was the game changer/mic drop moment, it would be the A7 SoC (launched

Like a handful of others at the time, I speculated that Apple was working on chips that could be used in a computer. Seven years later, Apple announced Apple Silicon, the M-series SoCs for Macs (and later iPad Pro and now presumably in their proprietary cloud servers).