How iCloud helped convict Paul Manafort

The former Trump campaign manager has reached a deal to plead guilty to federal charges, cooperate and avoid a second trial. How the longtime political fixer's misuse of Apple products and services, and poor operational security, helped bring about his downfall.

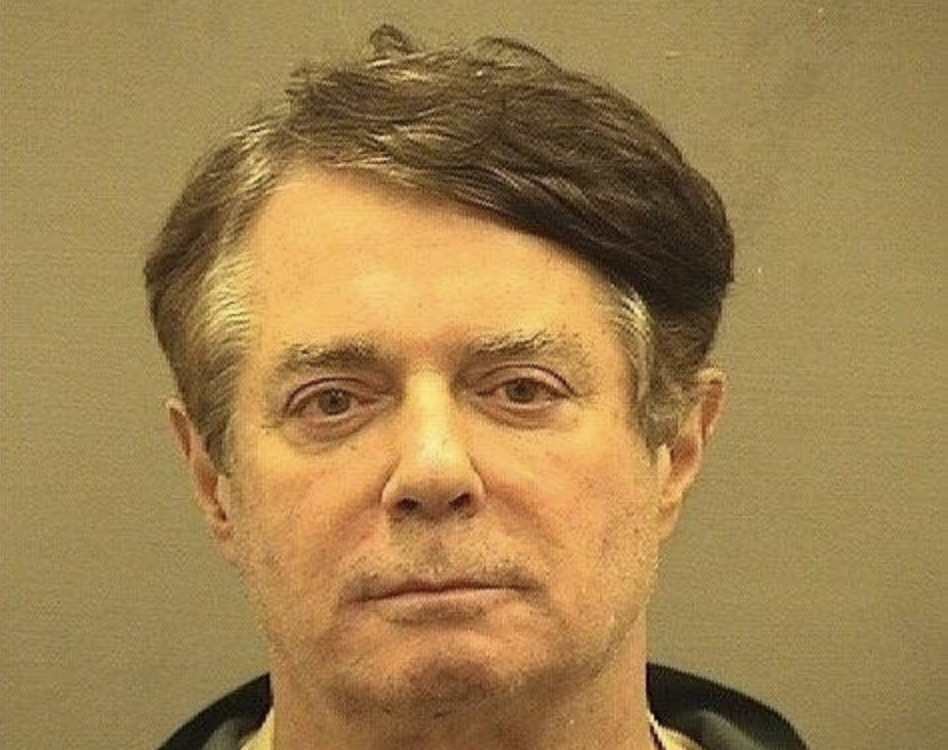

Paul Manafort, the longtime political adviser who for a time in 2016 was the chairman of President Donald Trump's presidential campaign, agreed to a plea bargain last week with the office special counsel Robert S. Mueller.

Manafort, who was convicted in August on eight counts of bank and tax fraud, has agreed to plead guilty to one count of conspiracy against the U.S. and one count of conspiracy to obstruct justice, CNN reported, citing court documents.

The agreement means Manafort will avoid a second trial, which had been scheduled to begin this month, while also agreeing to cooperate with Mueller's investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. It also means that Manafort has agreed to surrender $46 million from various accounts, an amount which is more than the entire cost of the Mueller probe itself up until now.

The obstruction count, in particular, stems from an unlikely source, Manafort's poor operational security in regards to his iCloud account. But that's only one way Manafort's enthusiasm for Apple products has surfaced in the case.

"20 Apple devices"

According to a motion filed by Manafort's attorneys, when federal agents raided Manafort's condominium in July 2017, they seized a large amount of electronic devices, including at least 7 iPods.

The document stated that the raid included seven iPods, four iPhones, one MacBook Air, one iMac (including one Solid State Drive (SSD) and one Hard Disk Drive (HDD)), two iPads, and single iPods and iPhones, which are listed separately. The motion had argued that certain devices were taken improperly, and that the Special Counsel had promised not to introduce evidence taken from the iPods "in this case."

National Security journalist Marcy Wheeler noted a semantic inconsistency, that the Counsel's office had only agreed not to use the iPod evidence "in this case," while making no such promise about other cases.

Now that Manafort has agreed to cooperate, "fully, truthfully, completely and forthrightly," and has agreed to turn over all relevant documents and materials, we may very well find out exactly what was on those iPods.

However, it's Manafort's use of iCloud that likely landed him in even more trouble.

The iCloud backup blunder

In June, after Manafort had already been indicted on several charges and was out on bail awaiting the first of two planned trials, he was jailed after being hit with additional charges of witness tampering. Manafort, prosecutors said, had improperly contacted two potential witnesses via WhatsApp. That Manafort had done so was discovered by the FBI via an unlikely source: His iCloud account. It turned out Manafort had been backing up his encrypted WhatsApp messages to an unencrypted iCloud account, which investigators obtained a court order to view.

Now we know Manafort has paid the price. The witness tampering count, to which he pled guilty on Friday, was connected directly to his iCloud blunder.

Most of the coverage in the tech press at the time pointed out just how sloppy Manafort had been with his operational security, appearing to commit crimes that were easily discoverable through unencrypted communications.

"What about San Bernardino?"

But in the months afterwards, an alternative talking point began to emerge: That Apple had done something improper by granting the FBI and Mueller probe access to Manafort's iCloud account. It was further argued that Apple is guilty of hypocrisy, in that they famously refused to create a backdoor for unlocking the iPhone belonging to one of the shooters in the San Bernardino terrorist attack.

This view was most clearly articulated in a Fox News segment from commentator Steve Hilton, which aired on Aug. 10.

On that show, Hilton floated a conspiracy theory that Apple's Tim Cook — as part of "the swamp" — was helping Mueller to "screw" Paul Manafort, and therefore the president. The evidence? Mueller formerly worked for a law firm that represented Apple. And Apple, in 2016, had refused to unlock the iPhone belonging to one of the accused San Bernardino terrorists.

"Another of [Mueller's] post-FBI clients was Apple," Hilton said. "Which among other things zealously guards its reputation for guarding users' privacy. Its pompous, sanctimonious, and hypocritical CEO Tim Cook has said that privacy is a human right, it's a civil liberty."

Hilton went on to bash Apple for refusing to comply with the order to open the iPhone in the San Bernardino case, and to charge them with hypocrisy for complying with a court order in the Manafort case.

"[Mueller] asks Apple for private information from its iCloud service, information relating to one Paul Manafort. So what does Mr. Privacy, Tim Cook, do? Sure Robert, we'll hand it over. The Apple iCloud data led directly to criminal charges against Paul Manafort. That's how it works- for Apple, for Mueller, for all of these swamp creatures."

This theory, perhaps needless to say, had quite a few holes in it.

"No collusion"

The lawfully executed warrant, signed off on by a judge, for Paul Manafort's iCloud data was not some outrageous overreach or civil rights violation. It was a completely unremarkable legal maneuver, one that uncovered clear evidence of a federal crime to which Manafort has now plead guilty, among other crimes of which he's been convicted. It also doesn't appear that Manafort's legal team ever challenged the legality or legitimacy of the iCloud warrant.

When a customer signs up for iCloud, they're agreeing that law enforcement authorities can get a warrant for information there. It's right there in the iCloud terms of service, to which Manafort and every other iCloud user agrees:

"You acknowledge and agree that Apple may, without liability to you, access, use, preserve and/or disclose your Account information and Content to law enforcement authorities, government officials, and/or a third party, as Apple believes is reasonably necessary or appropriate, if legally required to do so or if Apple has a good faith belief that such access, use, disclosure, or preservation is reasonably necessary to: (a) comply with legal process or request."

Apple has specific policies about complying with subpoenas for iCloud data. In this case, as in most like it, Mueller's team sought and was granted a court order to gain access to a customer's iCloud data. When that happens, obtaining the data from Apple isn't a matter of a special favor — they're actually required by law to comply. It's completely routine, and not the sort of thing that would require special intervention by Robert Mueller to Tim Cook. It's no different from a local police department having probable cause for a warrant to search a house for drugs or illegal guns, and then finding them.

Mueller did indeed work for Wilmer Hale, the law firm that has represented Apple for many years, most notably in relation to its protracted patent litigation with Samsung. But it's unclear whether Mueller ever personally did any work for Apple, and Mueller's name has certainly never been closely associated with any lawsuit, trial or other major legal dispute involving the company.

As to the comparison to San Bernardino, that case consisted of a completely different set of circumstances and issues. In that case, Apple was asked to develop a workaround to allow law enforcement to unlock a locked iPhone. An extraordinary measure to bypass its own security to get around an encrypted phone, is certainly very different from a request for unencrypted iCloud data.

There's one more, rather large inconsistency in Steve Hilton's argument about Manafort and iCloud. On Aug. 10, the very same night that segment aired, Cook was in New Jersey — having dinner with President Trump and the first lady. In fact, Cook has almost certainly spent more time in the last couple of years with the president he's allegedly conspiring against than he ever has with Robert Mueller.

Lessons of the fall

There are several lessons regular users of iCloud learn from what happened to Manafort. First, don't commit federal crimes. Second, if you're going to commit federal crimes, don't take a job as high-profile as campaign chief of a candidate for president of the United States. But if you feel compelled to do both, don't back up evidence of your crimes on your personal iCloud account.

Stephen Silver

Stephen Silver

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Michael Stroup

Michael Stroup

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele