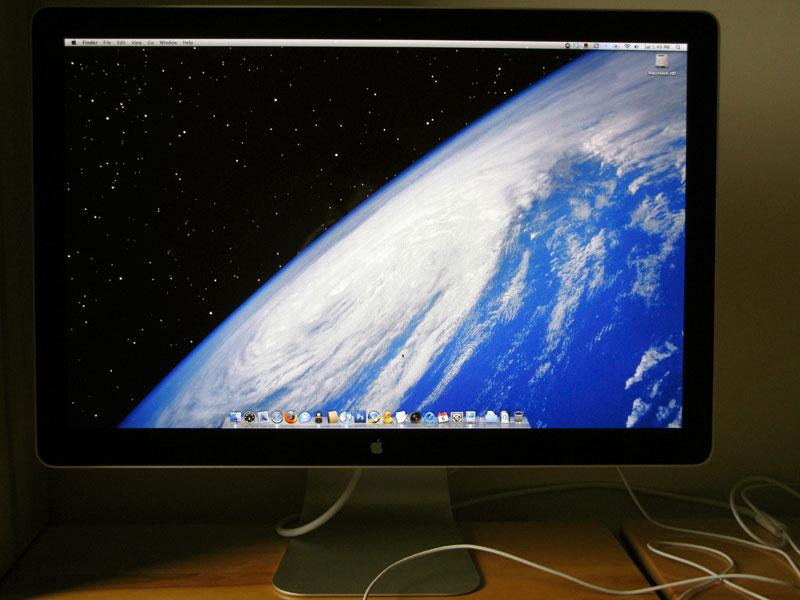

Apple's first major update to the Cinema Display line brings a much greener design and a raft of welcome feature updates, especially for MacBook owners. At the same time, a partial shift away from Apple's mainstay professional crowd makes one wonder where the company is going and whether it hasn't lost focus.

Despite being named after a movie theater, the Cinema Display was introduced in 1999 as a screen first and foremost for desktop-owning professionals; if you didn't have a Power Mac using the then-new DVI standard, you were effectively locked out of ownership. It resembled a painter's easel and had nothing but its video input for a connection, but its matte, undistorted, widescreen image was a boon for AV editors who needed both workspace and a more representative picture.

That all started to change in 2002, when the first DVI-equipped PowerBooks rolled out of Apple's factories. While the graphics hardware inside portable Macs was still somewhat anemic for a full dual-display setup to work well, it meant that PowerBook owners could buy a Cinema Display and use it as a desktop replacement. By late 2003, even the 12-inch PowerBook could make the pure digital connection to a Cinema Display — albeit through a bundled dongle.

Combined with the front-facing ports of the Power Mac G5, these more advanced portables helped shape the first complete redesign of the Cinema Display introduced in June 2004. Aside from a thinner and more adjustable aluminum enclosure, which was ultimately a hint at the design of the iMac G5, its biggest additions were a pair each of FireWire 400 and USB ports that made it infinitely more useful for not just peripheral-laden desktop users but also PowerBook (and later MacBook) users who wanted a permanent hub for their peripherals. At the time, it was embraced as a strong example of Apple finally answering longstanding requests.

After that, however, Apple fell silent. Beyond a quiet panel update in late 2005 and periodic price cuts, the displays had largely remained the same and increasingly felt like relics (which the 20- and 30-inch displays still do, as of this writing). In the meantime, third-party displays became increasingly less expensive even at the high end, where quality has improved as well; while there have been arguments made in favor of Apple's approach to color management, even Mac users have been known to joke in recent years that you bought a Cinema Display only to coordinate the fashion of your monitor with your computer. In some respects, the 24-inch iMac has been more suited to visual editing thanks to a significantly more modern LCD.

November of this year finally brought some relief through the LED Cinema Display, though this is the first instance in which a significant update to an Apple display hasn't represented a complete remake of the entire form factor; as we'll soon see, though, most of the real changes are on the inside.

By far the most obvious change is the black, glass-covered front, which is much bolder than it was in the past and clearly meant to give the impression of a seamless expanse rather than the conspicuous borders of the plastic and earlier aluminum models. It works and is useful for professionals who may previously have called out for black as a completely color-neutral backdrop for their work, but it has the unfortunate side effect of making the display slightly trickier to keep pristine; a careless grab at the edge is now likely to leave visible fingerprints, and dust is more conspicuous.

Most of the other visual touches are less noticeable but still pleasant to the eye. Although it's really just the same sort of trompe l'oeil that Apple has been using to give the appearance of a thinner design on virtually all of its 2008 products, the tapered back leads to a Cinema Display that no longer feels "fat" or simple in construction, especially with seamless edges that give the impression of a one-piece design.

This new shell is also more eco-friendly than in the past, as it scraps the plastic side fills of the sides and uses glass for the display cover. Apple also claims the screen is free of arsenic, brominated flame retardants, mercury, and polyvinyl chloride, though much of this is owed more to the LED backlighting than anything else.

Practically speaking, though, those who've had the opportunity to use the last-generation Cinema Display will feel right at home, for better or for worse. The "hanging" design isn't the most flexible and leaves portrait rotation and elevation out of Apple's display lineup. That said, we've never been especially uncomfortable with it in most conditions and still find benefits as well. It's easy to adjust the viewing angle or to turn the display (stand and all) to the right direction, and the space opened up beneath the screen is a convenient place to stow a keyboard or the debris that frequently accumulates during office work.

One caveat: in our experience, the MacBook's wireless reception strength dips significantly with the lid closed, so owners far enough away from their Wi-Fi base stations may see reduced speeds or occasional drops if conditions are sufficiently on the borderline.

Image quality and the gloss factor

Word has it that Apple isn't using the same LCD panel for the LED Cinema Display as in the 24-inch iMac, and we'd tend to agree; we've heard it may be a Samsung panel instead of the iMac's, which is virtually the same as for an NEC MultiSync display near-famous for its color accuracy.

Whatever the supplier may have done, the new stand-alone screen is still very close to the iMac in terms of day-to-day image quality. Colors still "pop," especially reds and blues; there's no noticeable grain, and viewing angles are still very wide (178 degrees from any direction) without producing the color inversion or washouts. Unlike the makers of some newer 24-inch displays that use cheap TN (twisted nematic) panels, Apple has chosen the higher road and is still using either PVA (patterned vertical alignment) or the top-end IPS (in-plane switching) for its display technology, both of which are much more comfortable and suited to color-sensitive editing. We're inclined to say IPS but will investigate further.

Significantly, Apple isn't using dynamic lighting to inflate its contrast ratio; that's unfortunate for gamers and movie viewers, but it's not as much of an issue for editors who may want a more consistent image.

Of course, the LED backlight is touted as one of the distinguishing features, and many other hardware vendors will say it improves color uniformity by lighting the screen more evenly. In our experience, though, about the only visible benefit — and the only one Apple trumpets — is the instant-on lighting, which doesn't exhibit the short warmup period you see with typical cold-cathode fluorescent backlights. If anything, the new Cinema Display is somewhat dimmer than the 24-inch iMac. Both are entirely bright enough, but the monitor-only unit often has to sit at two-thirds brightness or higher where the fluorescent iMac and the LED-lit MacBook are still very comfortable even at their lower settings. Either Apple has introduced more dramatic steppings to the brightness controls or else the LED isn't as powerful as it could be, even if it's perfectly fine for actual use.

With the use of a glass cover, though, Apple may have taken one of its biggest risks yet. The glass introduces a significant amount of gloss and, with it, reflections.

The impact of reflections is somewhat overstated by those most determined to avoid it; while you might notice at first, in everyday use with typical lighting conditions they're not often noticeable. Even at the bezel, where the always-black surface can act as a dull mirror, reflections are seldom distracting. We've even heard of artists or video editors consciously opting for the glossy displays, as the switch away from matte can actually produce a truer representation of the final color output and prevent someone using Adobe Photoshop, Aperture, or a similar suite from instinctively oversaturating the image before it's sent to the web or the printer.

Assuming conditions are ideal, that is. While in our testing the background was never really an issue, there are certain circumstances in which the gloss is unavoidable. Viewing a predominantly black website or other document in daylight will also let you view yourself, for example. And if you're unfortunate enough to sit in front of bright spot lighting (chandeliers, fluorescent ceiling lights, and certain floor-standing lamps come to mind), it may be hard to escape the reflection short of moving the display itself.

These conditions are usually only minor inconveniences to everyday users, but they're potential deal breakers for certain creative professionals. For those who aren't clinging to limited palette throughout the entire workflow, visible reflections make it harder to gauge the exact color value a subject should use or whether a portion of the image too bright or too dark. It can also be a nuisance when trying to look for fine detail that might be obscured by the image of a window background.

As such, these experts have to either carefully manage their lighting conditions or else consider another display. It's not a disaster, but it's a hindrance that was never an issue with the previous generation. Most entertainment-minded users don't object to matte screens, but many artists do object to gloss. The environmental tradeoff of glass just wasn't entirely worthwhile here no matter how many in the broader public might like it.

Apple clearly sees at least the 24-inch model in its third-generation Cinema line as a chance to bring some of the iMac's all-in-one design philosophy to desktops and to lid-closed operation for desktops, and it's this which has pushed the company to make the unusual decision to include full audio and a webcam rather than reduce costs further still over the old 23-inch display.

The LED Cinema Display uses the iMac's trick of piping sound through the bottom and bouncing it towards you. Surprisingly, though, it's actually a 2.1-channel setup with a dedicated internal subwoofer instead of the iMac's 2.0-only design. For internal speakers, they're much more appealing than those on the iMac or for most any other display saddled with often significantly underpowered stereo speakers meant only to satisfy office workers who just need enough to hear voice chats.

The system does a surprisingly good job of producing clear, warm-sounding audio: treble is very distinct (albeit not stellar) and bass isn't lost in the mid-range as it might be otherwise. There are many users who could depend entirely on the Cinema Display's speakers for entertainment, and they're arguably better than many $50-70 external speakers that can't get at least this basic audio range down pat.

Those expecting an audiophile-grade sound system will be disappointed, however, though it's not necessarily something Apple can avoid. Due to the small space and the absence of close contact between the subwoofer and your desk, the bass won't have the punch of a full 2.1 system with a subwoofer close to an appropriate surface. There's also a slightly hollow-feeling sound that reminds you the sound is being pushed out of an aluminum casing and not a perfectly designed wooden shell. Thankfully, serious listeners can automatically override the built-in speakers by plugging speakers or headphones into an attached Mac's audio-out jack, though this also leaves a significant portion of the display's value wasted.

A more universally helpful touch is the built-in iSight camera, which lets owners with lid-closed MacBooks (and most likely, future Mac minis and Mac Pros) hold video conversations without the expense and ugliness of grafting on a third-party camera. There's not much to say about the quality beyond what most computers' integrated webcams offer; it's still not perfectly quick on the draw, doesn't have focus or zoom and induces visible noise in low lighting. But it's convenient and certainly no worse than what you'd expect.

About the only real quirk was the default volume. When we first fired up the camera, the recipient on the other end complained that our voice was too quiet; it turned out that the output volume in System Preferences defaulted to a very low 23 percent and had to be bumped up to around 75 percent before every bit of spoken dialogue was at normal volume.

Less kind words can be said about the reduced expansion options. Further rubbing salt in the wound from the 13-inch MacBook's abandonment of FireWire, Apple has also scrapped the two FireWire 400 ports found on older Cinema Displays. This is admittedly not the gravest concern — how many owners actually plugged video cameras or audio breakout boxes into their LCDs? — but it also comes at the expense of expansion, as technical reasons dictate that the three USB ports are now the sum total of the display's expansion. It's evident that the base MacBook and the MacBook Air were primary concerns in the design process, and we can't entirely blame Apple for wanting extra space for that iPhone or still photo camera, but it's a step back.

The refocusing of the Cinema Display as a notebook dock becomes obvious with the built-in MagSafe adapter, which is there solely to charge MacBooks. It's arguably the one feature of the LED Cinema Display that simply can't be replicated by other displays, and it's a tremendous benefit for frequent road warriors; you can now leave your MacBook's power brick in a bag and off the floor whenever you're in front of the larger screen, saving you just a minute or two of time but a whole lot of clutter.

What might surprise most is the absence of a power button. Keeping with Steve Jobs' seeming fear of buttons, the new display reacts automatically. Plug a powered device (even a sleeping MacBook) into the DisplayPort jack, and it turns on; remove the cable, and it turns off. There's a certain wonderful simplicity to this, but it also limits your choices for when the display will activate. You can't turn the display off with the computer still running, and nor does the button serve to put both the display and the computer to sleep at the same time. It also makes unplugging peripherals difficult when a connected system is asleep, as there's no way to elegantly do that without first waking the computer and the display at the same time.

Some might also be disappointed with the absence of dedicated brightness or speaker volume controls. We don't see it as much of a problem given Apple's Mac and peripheral lineup for the past year. Any of these have keys to adjust both brightness and volume themselves, while Mac OS X also has software controls. It could be a hassle with non-Apple keyboards, however.

A word on DisplayPort and copy protection

Like with the MacBook, the redesigned display marks Apple's first venture into using DisplayPort for video input. From a performance standpoint, it's functionally equivalent to dual-link DVI but adds two-way signaling; it's hard to tell if Apple is using this newfound interaction at all, but it has the potential for future uses.

The particular implementation doesn't adhere to the official standard; Apple is instead using its own variant, dubbed Mini DisplayPort. This design is actually very convenient and makes for a far smaller, screw-free connection than even full DisplayPort. However, it also locks the display out of any non-Apple computer at present, and only the current MacBook range at that (other Macs are coming soon). There are no existing adapters to convert full DisplayPort, DVI or HDMI to use the display, so those hoping to use older Macs or non-Mac hardware will simply have to wait until if and when peripherals make the link possible.

But in contrast to the at times notorious Apple Display Connector, Mini DisplayPort should at least have broader industry support. The company has recently started offering free licenses to hardware and software makers and may ultimately get backing from rival notebook and video card designers looking to put video outputs into very small spaces.

Some have already railed against Apple's use of DisplayPort as buckling to pressure from overly protective movie studios, as users have already encountered problems with being locked out of movies on external displays that don't support anti-piracy encryption using High-bandwidth Digital Content Protection, or HDCP. To some extent, that's true; Apple wasn't technically required to use DisplayPort and could have insisted on keeping DVI and left purchased iTunes videos with no extra protection. The company was recently forced to patch QuickTime to loosen its restrictions, which until then were actually harsher than what the studios usually demand.

Nonetheless, it's important to separate the technology from the content, and DisplayPort is still a move in the right direction. The LED Cinema Display won't have problems playing any HDCP-encrypted videos, whether they come from the iTunes Store or not. And while movie studios have often been fairly open with standard-definition videos, many of these been less than generous with HD playback rights regardless of the platform. Apple has influence in online movie rentals and sales, but it can't force studios to offer content without HDCP limits or control what happens with Blu-ray videos (should Apple ever adopt Blu-ray movie playback). DisplayPort at least lets Apple continue to offer support for playback on external displays no matter how the battle over copy protection pans out.

Deciding what to rate Apple's latest display has been particularly difficult precisely because its value is entirely dependent on your choice of hardware and your lifestyle.

As an external display for a MacBook, or for most users of future desktop Macs, the display is excellent. It produces a vivid picture and could easily be called a lifesaver for Mac portable owners tired of tripping over AC adapters or plugging in several cables each time they revisit their desks. Apple's design is quick to set up and easy to use.

But for everyone else, the situation quickly complicates itself. In the time-honored tradition of next-generation Apple hardware, the LED Cinema Display alienates not just older Macs but even systems that technically handle DisplayPort but haven't used Apple's format. It's entirely likely that at least this 24-inch model won't leave the store without a MacBook following at the same time. That's no doubt what Apple would like, but it also sacrifices sales to users of any platform who might be in between system upgrades.

And of course, certain professionals or especially demanding home users simply won't want the display at all due to the gloss. Again, it's not terrible, but to exclude a significant portion of Apple's bread-and-butter pro market from considering an ideally-sized display is effectively throwing money away. Even if a future 30-inch display goes with a matte cover, those prospective buyers aren't likely to be upsold to the bigger offering — they'll buy elsewhere instead.

There's also the matter of priorities. A Cinema Display with speakers, a webcam and MagSafe isn't necessarily what people want. Without having a component pricing chart, it's impossible to say just how much Apple could have saved by stripping these features. However, in a fiercely competitive market for computer displays, dropping the price to $799 could potentially have picked up owners who wanted the least expensive color-accurate display possible.

As such, AppleInsider's rating shouldn't be used as an absolute gauge of quality, but rather a median point to help you know what to expect. If you're Apple's target user, you'll probably love it and may well rate it half a star higher or more. If you don't need the extras or you don't like the tradeoffs, the display could be strictly average or mediocre. It also won't appeal to buyers who are willing to exchange some image quality for a lower price tag.

From a purely technical standpoint, we like it. The picture is vivid, the sound is great for the class, and the design is both eye-catching and at times handy. We just hope that more Macs and Windows PCs can recognize Mini DisplayPort and that Apple doesn't end up sacrificing a large chunk of its display sales to high-end customers in the name of those few mainstream buyers who can spend the money Apple would like.

Rating 3.5 out of 5

Pros:

Good image quality at or near 24-inch iMac level

LED backlight is green and instant-on

Strong built-in sound

iSight is handy for video chats

Built-in MagSafe charging for MacBooks

Easily rotated/pivoted design

No external power brick

Cons:

Glossy display will scare away some (not all) buyers

Mini DisplayPort currently a MacBook-only standard

Expensive for those who don't need the audio, video or power features

No FireWire; one less port in total

No hardware power or brightness controls

Katie Marsal

Katie Marsal

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

198 Comments

sun + matte screen = unvisible dusty image

sun + glossy screen = reflective but visible image

also:

My current 20" cinema matte display is collecting dust in the outer corners. Impossible to wipe it off. And I can't imagine using my hoover to suck the edges clean!

The new 24" CD with its seamless edge display seems to be a sustainable blessing for keeping your screen tidy

So my question is about brightness control. Can the user change the brightness with the dedicated Apple Keyboard buttons? It just doesn't have an ambient light sensor?

AI feeds a lot of misinformation. First of all, the Cinema Display in 1999 did not have a DVI connection. It used Apple's ADC connector, which connected to the Power Macs and G4 Cube. You needed a $99 adapter if you wanted to use an ADC display with DVI. Later models of the Cinema Display switched to a standard DVI connection.

Second, AI claims that Apple could have used the DVI connection to avoid HDCP protection. Wrong again. ANY digital connection is subject to HDCP. The point of HDCP is to prevent the HD signal from being copied in its pure digital form. I guess people at AI don't own HDTV's. My first HDTV in 2003 featured the "new" DVI input for HD signals and it was HDCP compliant. Now that Apple is offering TV shows in HD, that is why HDCP is an issue, because the motion picture industry requires it. If Apple used an HDMI output on the MacBook/MacBook Pro, it would still have HDCP. Most importantly, who would want to watch their HD content purchased from iTunes on Non-HD equipment? If they think they see an HD image on Non-HD equipment simply because they bought the HD version, they are really dumb.

So my question is about brightness control. Can the user change the brightness with the dedicated Apple Keyboard buttons? It just doesn't have an ambient light sensor?

Of course. Reviewers just complain because they think there has to be a physical button for everything, and then they claim the product is somehow flawed because of that.

Of course. Reviewers just complain because they think there has to be a physical button for everything, and then they claim the product is somehow flawed because of that.

Yes but doesn't this also mean that if you use it in a dual display mode, you can't adjust the brightness of both displays individually? Cause that seems stupid...