Consumers vs. the Consumerization of IT

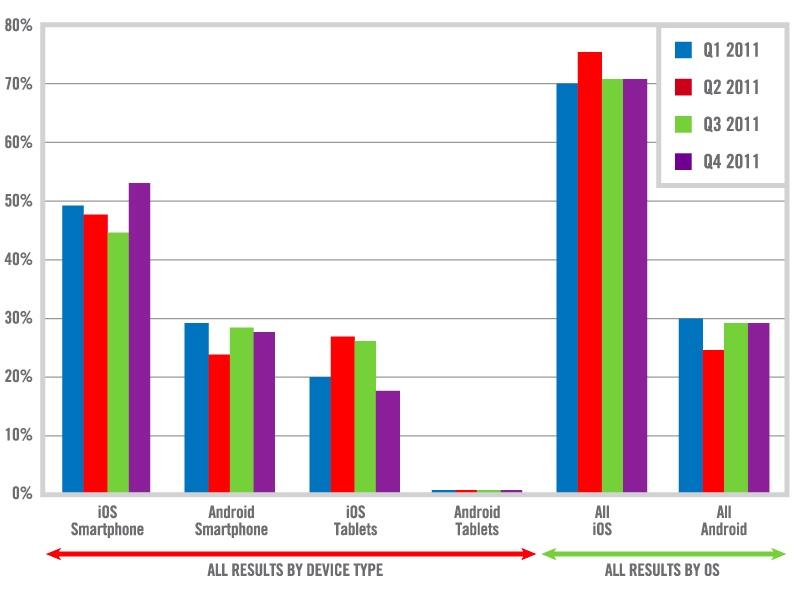

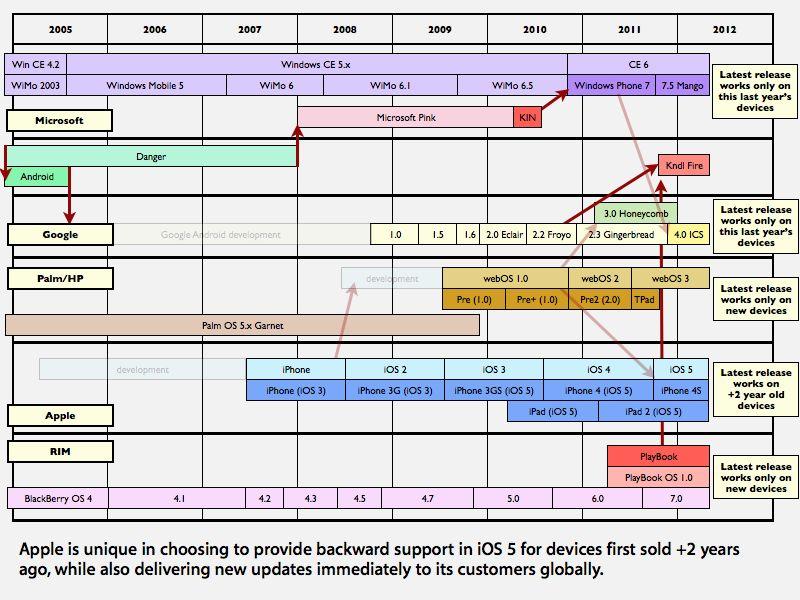

Over the past two years, Android has consistently mounted a strong promotional push early in the year: Verizon's Android 2.0 "Droid" campaign in early 2010, followed by the advertising blitz surrounding Android 3.0 Honeycomb tablets and a new generation of 4G, multicore smartphones early last year.

Both initiatives gave Android a big boost in mindshare among consumers who follow the mainstream tech media, particularly given Apple's silence surrounding its own competitive efforts. Outside of Apple's two iPad introductions, Android largely took over the mobile stage for the first half of both years.

Once Apple launched its response however, in the form of iPhone 4 in the summer of 2010 and iPhone 4S in the most recent holiday quarter, it became clear that Apple was still leading the industry. Super sized screens and LTE 4G data service haven't been enough to entice consumers away from Apple.

Among corporate users however, Android has had far less of an impact. On the surface, this might be puzzling given the strong trend toward BYOD or "bring your own devices," a consumerization of IT that has pushed corporate IT departments to support the devices their executives and employees want to use, rather than the devices the company selects for them.

How Apple entered IT

Historically, IT departments have selected the platforms and devices they are willing and able to support and have simply ignored alternatives, in some cases banning their use altogether as a potential security threat or a support burden adding unjustified expense. This long served as a natural barrier protecting the market for Intel-based PCs running Microsoft Windows and the Internet Explorer browser.

Over the past ten years however, a series of events conspired to open up the enterprise to new platforms and devices. Among these were the resurgence of Mozilla's Firefox as an alternative browser, combined with the growing stagnancy of Microsoft's own. Another pairing of events was Apple's introduction of the Unix-based Mac OS X just as Microsoft Windows began suffering a malware epidemic, which Apple capitalized upon in its "I'm a Mac" ads.

These pairing of flaws in the status quo and superior alternatives outside of it helped question the notion that a centrally standardized-upon monoculture was the best strategy in making technology decisions. It was the introduction of the iPhone, however, that really began to accelerate Microsoft's fading status as the brand "nobody got fired" for buying. While many people in IT continued to respect Microsoft's Windows, Server and browser products, nobody ever had much regard for its Windows Mobile offerings.

When the iPhone appeared as an easy to use, powerful mobile device with the world's first exceptional mobile browser, maps, Internet standard email with attachments and other features, it simply blew away Windows Mobile. Apple even began to make inroads into a business RIM's BlackBerry had long established as its own.

Microsoft helped accelerate Apple's ascent, licensing its Exchange ActiveSync protocols to Apple for use in 2008's iPhone OS 2.0 release, in an effort to establish credibility for its own Exchange Server for corporate push messaging at the expense of RIM's competing BlackBerry Enterprise Server.

Apple leveraged Exchange Server to gain entrance to the enterprise market, but didn't stop there. The company also worked to deliver a secure mobile development platform that met the demands of corporate users, along with adding support for corporate VPNs and proxy servers. By the 2010 introduction of iPad, Apple was already deeply entrenched among corporate users who needed mobile devices with more flexibility than RIM's text-centric BlackBerry platform and more power than the increasingly archaic alternatives running Windows Mobile 6.

The introduction of iPad expanded the iPhone's success from smartphones into an ARM-based tablet device that could challenge conventional WinTel PC with a cheaper, lighter, simpler alternative. The impact of iPad has been felt across the PC industry; its competitors are scrambling to follow Apple into both tablets and higher end Ultrabooks.

While Google immediately attempted to duplicate the iPad's successful formula, its Android 3.0 Honeycomb initiative clearly failed over the last year, paralleling the same reasons Google hasn't been able to find much adoption for Android among corporate users.

Consumer-centric devices not necessarily welcome in IT

A variety of exhibitors marketing cross platform, mobile device management solutions at this week's MacIT conference noted that Android remained a relatively small segment of the devices they support for clients, despite an apparent near tie between iOS and Android in the consumer smartphone market.

While Apple appears to have become wildly successful in winning over corporate users through the backdoor of attractive consumer-focused devices, the reality is that Apple has also devoted significant efforts to make its consumer products more attractive to corporate users. Mac OS X has progressively added support for features such as 802.11X wireless authentication, Exchange Server messaging, Active Directory and related networking sharing protocols. Apple's iOS has similarly made enterprise security and device management a key product focus.

In contrast, Google's Android platform, Palm's webOS and Microsoft's Windows Phone 7 have all focused on catching up with Apple in the consumer arena, particularly in courting developer support for apps and games as well as in delivering an exciting user interface that consumer pundits can describe as interesting, fresh and novel. Android has managed to position itself as the primary consumer alternative to iOS, becoming virtually indistinguishable to the average consumer looking for a smartphone that can play MP3s, take photos, watch YouTube and play Angry Birds.

Unlike Apple however, Google has not focused on delivering robust support for a set of features that are important to corporate users. Android still lacks the ability to connect to IPSec VPNs and has spotty support for Exchange Server. More importantly however, Android lacks strong support for management tools that corporate users can employ to monitor, manage and police the enforcement of their desired policies.

The fragmentation of Android means that managing Android devices is nearly as difficult as deploying custom software that can reliably run across a wide range of Android devices. Individual Android licensees have responded to this issue by creating their own efforts to support management features on select models.

However, this means that Motorola, HTC, Samsung and other brands of Android hardware all work differently, support different management features and use unique implementations, fractionalizing Android into various hardware-specific flavors. These code customizations also introduce issues that slow the rollout of updates and critical patches, while some carrier and vendor customizations actually expose new security vulnerabilities.

Rather than offering a cohesive platform suitable as a potential alternative to iOS, Android offers a complex array of individual support options that, together, lack the critical mass Google's platform is supposed to offer. This makes Android-branded devices as problematic for corporate users as the incompatible variations of JavaME-based smartphones they replaced. The non-integrated "open" development of Android does not appear focused on solving this issue.

Instead, Google has allowed its hardware partners to develop their own device management solutions while it focuses on delivering support for initiatives like NFC Google Wallet, which are more directly tied to revenue-generating opportunities. This indicates that Android's smaller and shrinking share among corporate users isn't likely to reverse its course any time soon. Instead, it will continue to meet new competition in the corporate arena from Microsoft's Windows Phone 7 smartphones and its Windows 8 tablets later this year or in early 2013.

Challenges facing Apple in the enterprise

Meanwhile, Apple continues to gain ground in the enterprise, both at the expense of alternative smartphone platforms and the conventional PC, which is getting hammered on the high end by Apple's Thunderbolt-equipped MacBook Pro and MacBook Air while also losing ground the affordable and mobile segment due to the dramatic uptake of iPad among corporate users who want a simple, manageable platform that's easy to support and develop custom software for.

Apple also faces challenges of its own. If the company wants to capitalize upon its initial success in the enterprise, it will need to continue to deliver top tier support for the features that matter to corporate users. The company appears to be backing out of the Mac OS X Server business, something that could eventually give Microsoft an edge with its alternative Windows Phone and Windows 8 platforms if it chooses to prioritize support for its own platforms ahead of iOS in future Exchange Server features.

Apple has historically also trailed PC makers in providing the kind of product support enterprise IT users expect to have available, including on-site support. From his background in operations (and his prior position at Compaq), Apple's new chief executive Tim Cook appears to have a greater appreciation for the real world, often pedestrian needs of corporate IT departments than Steve Jobs, who enjoyed the luxury of being able to develop custom IT solutions at Pixar, NeXT and within Apple as he turned the company around.

Cook, along with Apple's iOS head Scott Forstall, now face the parallel tasks of keeping Apple's devices fresh, exciting and appealing to consumers while also keeping them reliable, manageable and well supported for IT departments. Right now, the company faces little real competition matching its efforts in either arena, but history indicates that Apple's largely unchallenged market position isn't likely to last long.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

-m.jpg)

86 Comments

No, this post is wrong. slapppy told me so.

No mention of the iPhone Configuration Utility. This is important to Apple's seriousness when entering the enterprise back in 2008. Along with licensing of Exchange ActiveSync they created a tool that worked on both Mac and Windows OS right from version 1.0.

Corporate IT departments are used to managing PCs, and with it's enterprise feature set, the iPhone is closer to a PC than Android, closer to what they're comfortable with. But I wonder what will happens if MS ever get their act together in this area (e.g. Win 8)

No, this post is wrong. slapppy told me so.

I keep telling you guys, Slappy is an Apple plant here.

Tiny error in the graph, all Windows Phone 7 devices are upgradable to Mango.