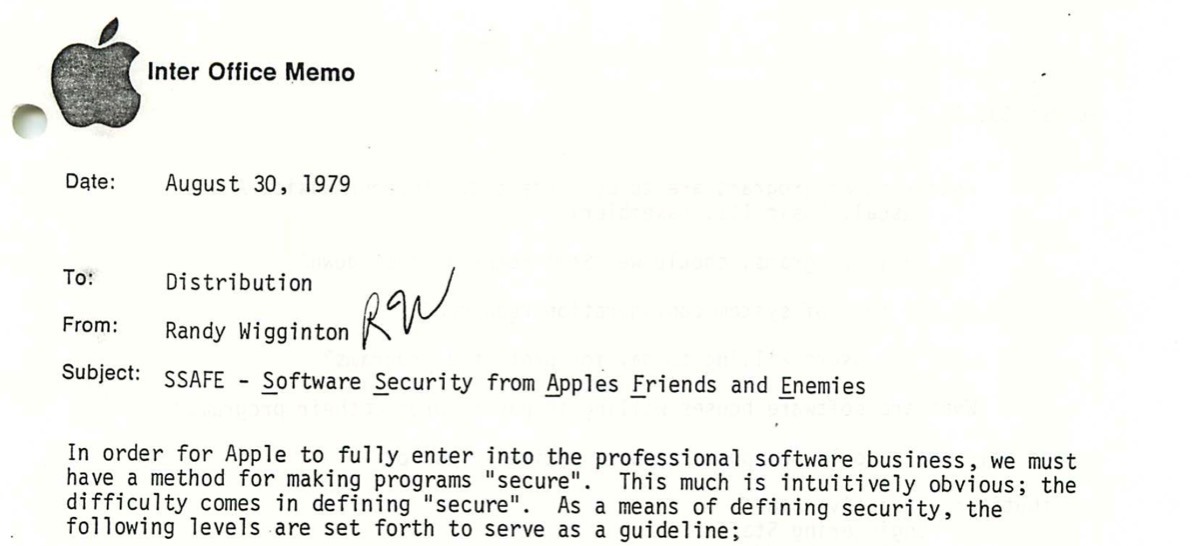

Published on Wednesday in a blog titled Applememos, the 116 pages of collected notes and memos details Apple's "SSAFE - Software Security from Apple's Friends and Enemies" initiative, to develop, implement, and ultimately sell copy protection routines for software. The memos, apparently belonging to Apple engineer and section leader Jack MacDonald, span from Jan. 10, 1979 through Jun. 25, 1980.

While apple co-founder Steve Jobs isn't mentioned in the paperwork, co-founder Steve Wozniak is on the distribution list. Early Apple engineer Randy Wiggington features prominently in the correspondence.

Based on the memos, the initiative was launched shortly after the release of Apple DOS 3.2 and the auto-boot capable Apple II plus, and deployed in part in DOS 3.2.1.

The notes cite the need for a protection system to preserve both business investment in hardware and software, as well as a way to continue the earning potential of developers. A hand-scrawled memo suggested that businesses selling software would be interested in paying "a lot!" for a workable system.

Apple apparently initially envisioned a system with several layers of security. Originally, the software prohibited users from using normal file system commands like RUN and CATALOG to duplicate software and diskettes.

Countermeasures were quickly implemented by the user community, with programs like Locksmith and Copy 2 Plus allowing for the protected software to be copied despite Apple's early efforts.

Very shortly after the initial, easily circumventable, security measures were implemented, Apple moved on to examining serial number validation. The measure was mostly dismissed as an Apple-provided solution, calling it "costly and error-prone" needing diskette customization during the mass-manufacture process.

As the debate, and the technology, marched on, Apple considered a "key module" approach, similar to that used for copy protection in the '90s with serial and ADB "dongles" authenticating users.

While the memos overlap the 1980 release of DOS 3.3, it is unclear what advances were made in the routines for future releases.

The routines appear to have remained mostly intact throughout the silent updates of DOS 3.3 through the Apple IIe years. Some routines followed into the Apple III SOS-derived ProDOS system, implemented in 1983, with a final official discontinuation in 1993 — but enthusiasts continue to improve the software.

Throughout the '80s, it mostly remained up to software vendors themselves to implement copy protection schemes. It is unknown exactly how many titles used Apple's protection routines developed for the SSAFE program.

Apple SSAFE Project by Mike Wuerthele on Scribd

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

11 Comments

Early copy protection - what a good subject. Software was pretty expensive back then. $25 or so for a game is more than I ever pay for a game now. Apple was right to protect the developers. Even in those days before the web, folks connected to BBSes to trade software. The 2(c) technique was relatively easy to defeat. The original disk would have a bad sector and the software would check the bad sector. If it wasn't bad, the software wouldn't work. When you copied the disk, you don't get the bad sector on the copy. On the Ataris at least, when you opened up the drive there was a potentiometer to control the drive speed. If you cranked the speed all the way up or down, you could write a bad sector with a sector editor (and then put the speed back where it belonged so you could read/write normally) and this would pass the copy protection check. More knowledgeable people would modify the code, of course.

I bought a C64 in 1986, chiefly because I had friends with stacks of copied discs. All you needed was a great willingness to swap discs in and out (and the copying software). (Why didn't one of us just bring our floppy drive with us?)

I worked for an educational software publisher in those days. We had an app where every grade level used the same app but used different data discs. And in those days, if you copy protected discs, you had to provide backups. So if a school bought a program for grades 1-6, they wound up with 12 copies of the application disk. They could have sold or given away 10 or 11 copies to other schools and made copies of all the data discs (which were unprotected because it was too expensive to provide backups of all those). So we used some hidden sector trick (I forget the details) that tied the data discs to the app disc the first time you used them, but the schools had to go through some procedure to set it up and they usually did it wrong and we'd have to "reset" their discs. We finally gave up and just trusted them instead.

While certainly some businesses used Apple II's, Apple was never really big in the business market and especially not after the first IBM PC was released. I remember trying to create a database system for my father-in-law who had an optometry business, but before affordable and practical hard drives, I couldn't make it work.

At the educational publisher, we had another program which was a test scoring and evaluation program. The second iteration of that program wound up having three different floppy disk types: the program disk, a disk with the test and prescriptive data and a diskette with student data. Even with double-drive setups, the users had to constantly switch disks. In retrospect, it was amazing people were willing to do this, but it did seem state-of-the-art at the time.

Apple did do very well in the education market and as has been told many times in accounts about Apple, the Apple II kept the company alive for a number of years after the Mac was released and was losing money.