Twenty years ago today Steve Jobs introduced iMac, an ambitious new Mac aimed specifically at easy Internet access. It not only redefined the design and styling of tech products but charted a strategic course that would take Apple from being a minority PC maker to the world's most valuable tech company. Most importantly, iMac had an impact because it courageously made bold decisions that conventional thinking assumed to be wrong.

Back on Track with iMac

Just ten months prior to the iMac introduction (at the May 1998 event the company named "Back on Track"), Jobs and his hand-selected management team had taken over control of Apple and killed a series of projects and products to focus the company on two simple product lines: the 1997 white desktop Power Mac and a curvey black notebook PowerBook, both powered by a G3 processor. iMac was a unique opportunity for Apple to show off its core competency in making advanced technology widely accessible

Those two products were optimized for Apple's existing customers: mostly creative professionals attracted to Apple's intuitive, esthetic Mac software.

With iMac, Apple was taking aim at a broader market of individuals who wanted a practical, easy way to get on the Internet.

While that sounds basic today, in 1998 iMac was a unique opportunity for Apple to show off its core competency in making advanced technology widely accessible and attractive. That strategy would play out again with Apple's iBook consumer notebook in 1999, the iPod music player in 2001, iPhone in 2007, iPad in 2010 and Apple Watch in 2015.

To introduce why the world needed Apple's new iMac, Jobs first detailed what was wrong with entry-level consumer PCs: they were slow, using outdated processors; they were generally not ready to connect to networks and they used "old generation I/O," including PS/2 connectors for keyboards and manually configured legacy serial and parallel ports for other devices (requiring users to load software drivers for each device they installed). And they were ugly, Jobs pointed out.

A fast G3

Before unveiling the new iMac, Jobs outlined how it would be different. For starters, Apple was using a modern 233MHz G3 processor, the same chip it had used in its entry-level Pro Power Mac G3 just six months prior at a price $300 higher.

That new generation Power PC chip boasted a performance edge "up to twice as fast" as Intel's Pentium II processors at similar clock speeds, a line promoted by Apple in commercials portraying Intel's chip as a snail and its chip designers dancing in "toasted" bunny suits.

The iMac's new G3 also outperformed the high-end Power Macintosh 9600, which the company had just introduced a year earlier starting at $3,700 (about $5,700 in today's dollars, adjusted for inflation). The new iMac arrived just as the PowerPC architecture was hitting its stride, and it made the affordable machine fast and capable compared to other PCs.

Focusing on its unique performance edge was something Apple again repeated with the Firewire-based iPod in 2001, G4 and G5 processors in successive Mac models, and it turned into core strategy for Apple in mobile devices with its custom A4 chip in the original iPad and iPhone 4. Since then, Apple's aggressive enhancement of custom A-series processors have kept it ahead of the rest of the mobile industry.

Most recently, Apple has moved into custom memory controllers and its own mobile GPU development for iPhone 8 and X, and introduced W-series chips that give a silicon advantage to its AirPods and Beats wireless products. While Google and Facebook are applauded for talking about their plans to introduce custom chip development, Apple has long been doing its silicon work in secret and then introducing its advanced chip technology only after it has an edge to demonstrate.

Ethernet and USB

At a time when PCs generally needed an external modem to connect to the Internet over phone lines, the new iMac built in both its relatively fast modem (making it easy to connect by only plugging in a phone cord) and 100Mb Ethernet. That made it ready-to-go for education and for the emerging world of home networks and DSL internet service.

Jobs at the time noted that about "ten percent of homes in Silicon Valley were already being wired up for Cat 5," while also poking at consumer PCs, few of which had any provision for networking built in. Additionally, the new iMac "courageously" adopted an entirely new type of port developed by Intel: Universal Serial Bus or USB.

With USB, consumers could simply plug in a device and the system would configure itself to use it, in most cases selecting its own driver and adapting all the setup required on its own. And rather than having totally different cords and connectors for the keyboard, a printer, an external disk and a flatbed scanner, USB could serve a range of uses with one simple port, even chaining multiple devices in a hub.

USB ports had already appeared on PCs, but it generally sat unused because device makers kept building slightly cheaper products using RS-232 serial ports, PS/2 cables for keyboards and mice and Centronics Parallel ports on printers and disks. The inherent problem of legacy ports favoring "techy but cheap commodity" over "technically advanced, ease of use" were much easier for Apple to ditch because it could differentiate with a premium experience rather than competing only on price as most PC makers were.

The new iMac also included IrDA, a way to beam (like a TV remote) data using invisible light. It wasn't nearly as fast as the wireless technology Apple would roll out in the future, including Bluetooth and WiFi, but it offered an early way to transmit photos and other basic data without requiring cables at all.

Apple brought WiFi into the mainstream with iBook the next year and pushed out regular advancements to both WiFi and Bluetooth. It rapidly deployed BLE starting in 2011, before other platforms saw the value in it. Apple also pioneered the development of extremely easy ways to take advantage of wireless connectivity, including AirPlay wireless distribution and a suite of Continuity technologies including Handoff and AirDrop.

The company's aggressive pushing of wireless connectivity has enabled it to deliver ultra-thin mobile devices with just one connector, from iPod to iPhone and iPad, and most recently even entire computing platforms that lack any ports at all, including Apple Watch and the new HomePod.

Other companies have meekly sought to avoid rustling any feathers by holding onto old legacy ports and cords, including the most recent henhouse dustups involving the analog audio jacks on newer iPhones, the clucking about dongle-armageddon related to modern MacBooks and the sky-is-falling cock-a-doodle-do about HomePod's lack of auxiliary cable inputs. Yet over the last 20 years of irritated rooster crowing from the pundits, Apple's approach has appeared to lay all the golden eggs.

"The back of this thing looks better than the front of the other guys"

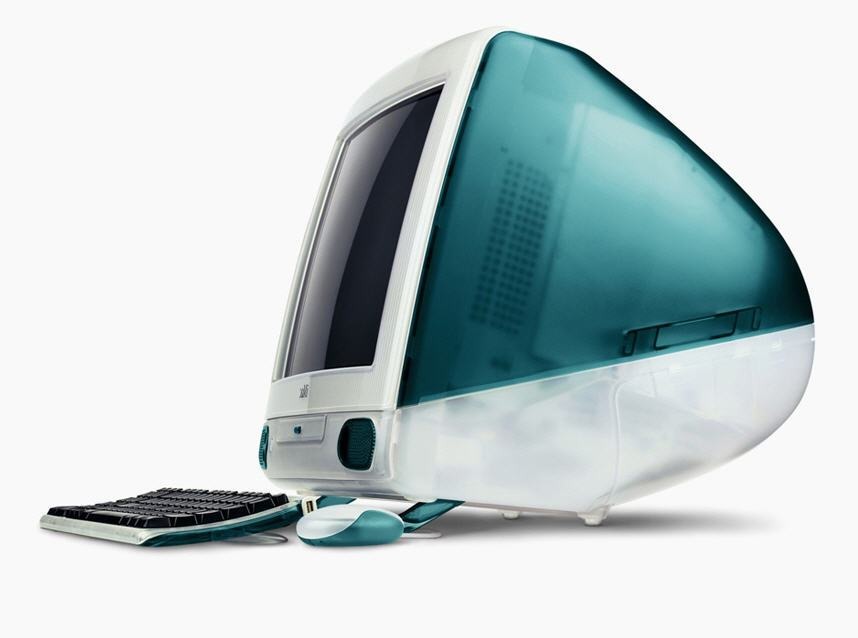

After detailing all of its technical achievements, Jobs then dramatically unveiled the new machine as an all-in-one enclosure built using translucent plastic inspired by the crystal blue waves at Bondi beach.

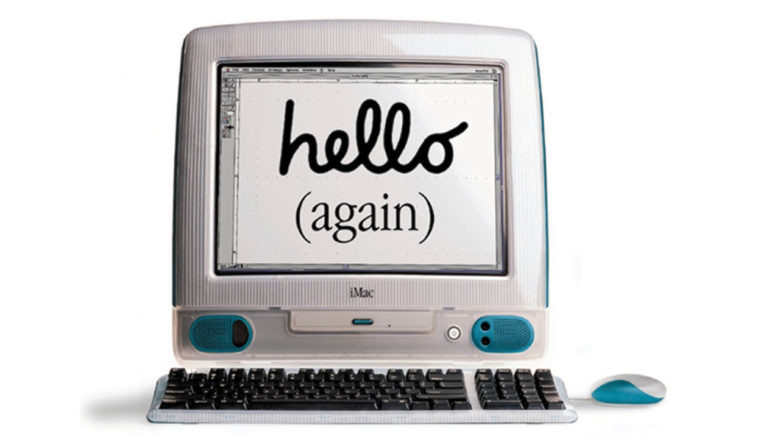

Jobs showed off the iMac's face with stereo speakers and a CD-ROM tray below its 1024x768 15-inch display (Jobs noted most PCs used low quality 13-inch screens) with a handwritten "hello again" (an homage to the introduction of the original 1984 Macintosh). He then had a wireless camera operator take two full passes around its sides and back, showing its concealed ports, see-through rear panel and a carrying handle.

"The back of this thing looks better than the front of the other guys, by the way," Jobs said as he detailed the thought that went into its design.

The End of Beige

Back in 1998, I was stuck at work behind a desk at San Francisco General Hospital during the iMac launch. There were no live event video feeds on the web. However, I did rush to load Apple's website to read up on what new stuff Jobs had introduced. For the iMac launch, the Apple.com site featured a then-novel animation of the new iMac, so when you loaded the page you'd see (after a moment of loading delay) the new machine rotating in space as it grew closer before it introduced itself as "iMac."oh no Apple... this is not conventional thinking

I was briefly struck with the sinking feeling that perhaps Apple had done something too risky. A translucent, rounded computer? A one-piece design that included a monitor? Don't people want to open up the side of their PC and plug-in expansion cards, and won't they want to replace the PC components faster than their monitor?

This moment of "oh no Apple... this is not conventional thinking" was one of the first times in my life where I had to step out of my comfortable understanding of What Had Always Worked Before and consider that maybe instead of being afraid of this new and different future unfolding in front of me, I could freshly evaluate whether it might actually be a big improvement over the status quo. Maybe the world was indeed ready for iMac's bright candy-colored translucency that could distinguish Apple from all of the look-alike PCs running Windows.

Computers had been beige boxes ever since Jobs had brought the Apple II into the mainstream in the late 70s with a foam-molded plastic case that evoked the appearance of a futuristic replacement for the typewriter. It stood out in an environment of industrial looking PCs in sheet metal cases with exposed screws and seams.

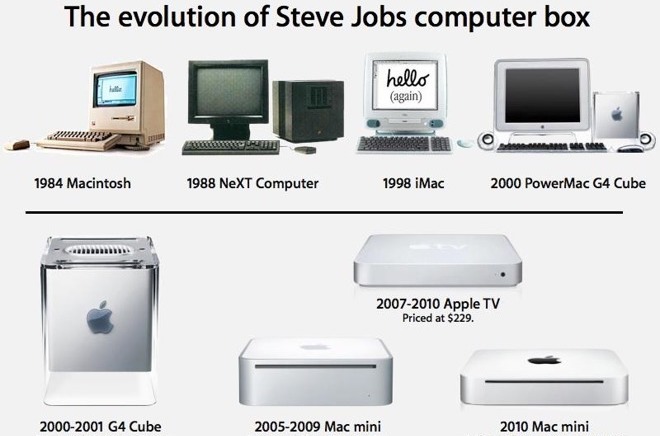

The boldest changes in the PC industry across the next two decades of personal computers also had Jobs fingerprints: the integrated Macintosh of 1984 with its small but accurate display and the stark black cube Jobs had introduced for NeXT in the late 80s. However, both products had shown that being advanced and distinctive wasn't enough to be wildly successful right out of the gate. And that fact likely helped keep the PC industry sheepishly boring.

The new Apple, with Jobs at the helm, was laying out a new strategy that sought to boldly attract attention while being technically competent, and at the same time also pragmatic, affordable and accessible to regular people.

My cautious optimism at the first sight of iMac was encouraged by strong sales and consumer satisfaction. And in parallel, my skepticism of the conservative group-think naysaying that routinely targeted Apple was kicked into hyperdrive as waves of pundits took turns explaining why iMac was a terrible idea that wasn't going to work.

iMac's Critics

Unsurprisingly, Windows PC-aligned critics thought iMac's price tag would be a non-starter, given that they could go out to Frys and buy a metal box and various components and spend the day assembling a machine with better specs and have enough money left over to buy a license for Windows.

But even the many pundits among the Mac Faithful were displeased by the iMac, quibbling that Apple should have built in legacy ports so that people with a mountain of ADB keyboards and GeoPorts and AAUI networking cables and MiniDIN RS-422 serial devices (what about the Palm Pilot!?) could be accommodated. Sound familiar? Those same voices today want the iMac's 20-year-old USB-A port on brand new MacBook Pros.

iMac also kicked off a vocal contingent who began preaching a gospel of the "Headless Mac," demanding that Apple sell a computer without a display, so the screen could be reused across many generations of this upgradable box. However, 20 years later iMac has served as Apple's most successful desktop Mac while headless Macs, including the Xserve, G4 Cube and Mac mini, have sold so poorly that they were all effectively discontinued.

There were also legit criticisms of iMac. While Jobs crowed during its introduction that it had "a great keyboard and mouse," actually "the coolest mouse on the planet" and even "the most wonderful mouse you've ever used," its round USB mouse (despite looking distinctive) was a frustrating design because it had no clear orientation, making it easy to grab off angle.

Apple eventually addressed that (after inflicting its "hockey puck" USB mouse on the next two years of Macs!) but has since released other "coolest! most wonderful!" devices with the same issue— including the Apple TV Siri Remote and iPhone X— both of which are easy to pick up upside down and require a glance to orient in your hand placement before using.

Unlike the iMac Mouse, Apple's more recent, perfectly symmetrical devices have compelling features that make it easy to get past such a First World Problem as having to briefly look at the technically advanced device you're using. For many users, the iMac's bundled USB mouse was annoying enough to spark a third party solution: buy an aftermarket pointing device that works the way you like.

This had the effect of inducing a new supply of USB devices specifically for iMac, driving down the price of USB peripherals (combined with the reality that legacy port devices in many cases simply couldn't be used with iMacs) and eventually helping the PC world to get on the USB train as well. This also helped Apple to deploy USB across its other product lines faster, and to eventually get rid of legacy ports there, too.

iMac Impact

In the two decades since Jobs first unveiled iMac as a stylish new fast computer for regular people to access the Internet, technical advancements have continually refreshed its design. Four years later, Apple introduced its first LCD-based iMacG4 using a distinctive "igloo" design and a complex hinge. This set Apple on the path of getting rid of environmentally troublesome CRT screens entirely.

iMacs also adopted WiFi, Bluetooth and Gigabit Ethernet, and by 2002 Apple shifted its Macs to the new macOS X platform, its advanced Unix-based operating system using advanced application development technology from NeXT.

At the beginning of 2004, I complained that the "Luxo Jr" design of iMac G4 "is awkward to carry, and worse to service. It requires a special foam mold to lay it on its side to prevent it from rolling around or stressing the display," and suggested that Apple "just take a Cinema Display and slap three inches of Mac on the back. Nobody cares how thin the Cinema Display is; it takes up the same space with or without that Mac backpack attached anyway. Schools would love it; designers would love it; shoot, anyone with a desk and no desire for a large tower underneath it would love it."

That's exactly what Apple did with the iMac G5. By 2006, Intel's processors had outpaced the potential of PowerPC, so Apple adopted its new Intel Core chips, starting with iMac. At the same time, Apple had been investing in a mobile future for the Mac platform, while also developing its iPod ultra-mobile devices. The next year, Apple shipped iPhone: a mobile-optimized version of what the iMac had been a decade earlier: a simple, affordable way for regular people to access the Internet.

As mainstream consumers have shifted toward mobile iOS devices to access the web and mobile-optimized apps, iMac has evolved into a higher-end desktop experience with speedy Thunderbolt connectivity (2011), an ultra-thin case using friction stir welding, fast SDD storage and larger displays— up to the incredible 27-inch screen of iMac 5K and its beefy partner, the 8 to 18 core Intel Xeon-based iMac Pro that Apple released last year.

The strategy behind the machine that defined the new Apple— and challenged the status quo— continues to show up across Apple's product line: its attention to good design, its speedy performance driven by premium components rather than commodity pricing, its intent to reduce port complexity and cable clutter, its super-simple ease-of-use and ready-to-go design are now trademarks of virtually everything Apple makes.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

53 Comments

Having bought many iMacs over the years, while the form of the Luxo lamp was brilliant and the current model is the most beautiful, I reckon the G5 design was the best, a proper balance of form and function.

The iMac G5 insides were easily accessible and repairable. People bragged about how it’s insides looked better than the outside of competitors.

People complain about today's Macs being hard to fix, but that first flatscreen iMac with the round base with a huge PITA to work on. The RAM was accessible, but the HDD was near the top of the base so you had to get though each layer of boards to get to it, as I recall.

Yes, the luxo lamp version was brilliant form but a PITA to work on. I once had the idea of putting a Mac mini inside one. Had to give up as I could not get the monitor to connect up.

I like looking back - my favourite era from then for another 8 years or so.

I'd have to disagree about the G5 iMac. Too many failed logic boards and power supplies have scarred my memories of it.

The Sunflower iMac was a great machine, I don't recall taking the drive out being too painful, but that may be wishful remembering :hushed: