Apple and Samsung on Wednesday at last concluded their long-running fight over several iPhone patents, with both parties agreeing to settle remaining claims and counterclaims.

As a result the court has denied Apple's motion for supplemental damages, as well as pre- and post-judgment interest, according to documents filed through the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. Samsung, for its part, is giving up motions to invalidate Apple's '915 patent, seek alternative relief, and toss a recent verdict.

Exact terms of the deal have not been made public.

The last retrial

After days of deliberating, a federal jury handed down its most recent decision regarding the Apple v. Samsung case on May 24, declaring the South Korean tech giant owes $533,316,606 for infringing on Apple's iPhone design patents. Another $5.3 million was awarded for two utility patents.

Samsung lawyer John Quinn told Judge Lucy Koh he had some issues with the verdict that would be addressed in post-trial motions. Based on the filing, it appears that Quinn's concerns have either been addressed or dismissed.

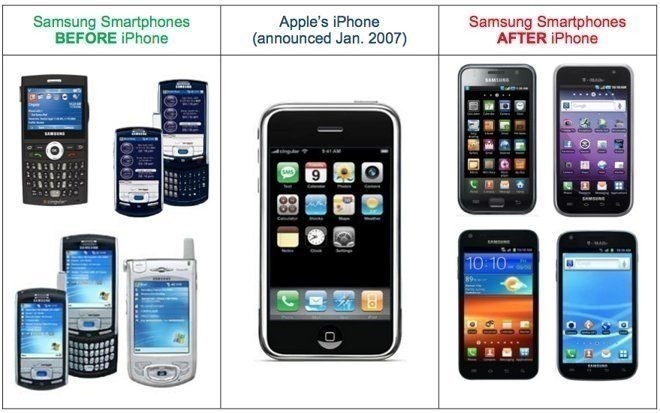

The trial is a continuation of the courtroom battles between the two tech giants, which first took place in 2012, a time when Apple was awarded $1 billion in damages. It was found by the court that Samsung had violated a variety of Apple's patents, including those for the "Bounce-Back Effect" and "Tap to Zoom."

A settlement appeared to be reached in 2015, reducing the amount to $548 million, while the case continued to go through the appeals process.

In late 2016, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously in Samsung's favor in December 2017, deciding that design patents only cover individual smartphone components and not the entire mobile device. The ruling meant the case was sent back to a lower court for a damages re-determination.

As part of the new trial, the burden was not on Samsung to disprove the entire smartphone is an "article of manufacture," but instead, Apple had to defend its assertions. The iPhone producer had to convince the court that the infringed patents apply to the whole product, not individual components.

In the latest retrial, the jurors determined how much Samsung had to pay Apple as part of the infringement, rather than whether the infringement took place at all. While Apple wanted a full $1 billion for the infringement, Samsung had previously advised it was willing to pay $28 million.

The first witness in the trial was Apple marketing VP Greg Joswiak, testifying that design was an important part of the company, critical even before the 2007 debut of the iPhone. Apple attorneys showed the jury photographs of products including Macs, iPods, Powerbooks, and MacBooks to drive the point of design being "in the DNA of the company."

As Apple was "betting the company" on launching the iPhone, Joswiak noted this caused Apple to file for a vast number of patents to protect its design and other elements, such as communications techniques.

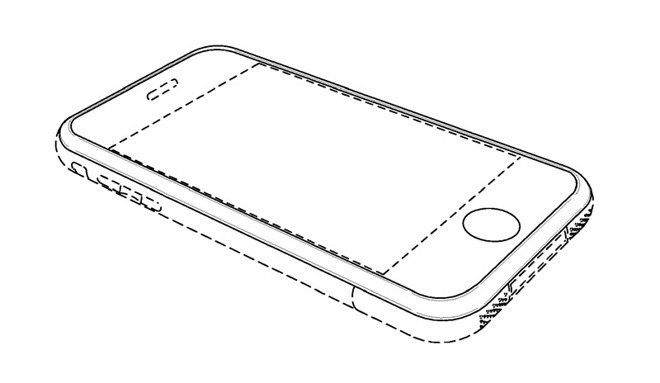

Apple expert witnesses Adam Ball and original Mac designer Susan Kare argued the merits of Apple's patents. Importantly, the pair sided with Apple's legal team in viewing three granted designs as applicable to iPhone's "articles of manufacture."

Samsung's lawyers did manage to get concessions from both Ball and Kare, acknowledging smartphones are made from individual components. Kare admitted "I get that a display screen is a thing," and agreed that Apple's patent illustrations included dotted lines that, while providing a complete picture of the iPhone concept, are not necessarily covered in its claims.

Ball conceded the iPhone could be dismantled into parts, but stressed the Jury should keep focusing on the final design. "Just because you can take something apart doesn't mean it was designed to be that way," said Ball. "If you replace [a component], you're trying to get back to that thing that you bought."

Samsung's expert witness, accountant Michael J. Wagner, largely discussed the Korean giant's accounting practices. Asked by Apple counsel Bill Lee if Samsung balances its sheets by tallying profits from components, Wagner said "no" to each item.

Lee's questioning seemingly tried to prove that Samsung also believes that, from a financial standpoint, an article of manufacture is the whole device and not individual parts.

Wagner also confirmed Samsung made $3.3 billion on the sale of 8.6 million smartphones that were found to have infringed Apple's design patents, but that figure is based on taking the entire mobile device into consideration, not specific infringing components.

In the closing arguments, Apple lawyer Joe Mueller reiterated expert witness points, declaring "the fact you can pull apart a phone means absolutely nothing. The question is what did they apply those designs to. It's not a pane of glass. It's not a display screen that doesn't show a GUI. It's the phone."

By contrast, Samsung lawyer John Quinn told the jury "The Apple design patents do not cover anything on the inside of the phones. They don't even cover the entire outside. Under the law, Apple is not entitled to profits of any article of manufacture to which the design was not applied."

Roger Fingas

Roger Fingas

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

39 Comments

So does Samsung pay Apple anything? This article doesn’t say either way. Might this settlement indicate Samsung really wants to get the manufacturing contract for the A12? Is this a win-win or lose-lose for the parties?

update: other websites are saying the terms of the settlement have not been released so we may never know. Let the rumor mill run wild.

AI Apple critics: Samsung won. Evil Apple.

AI Apple supporters: Apple won. Evil Samsung.

I guess the big question is how little did Cook settle for? They will probably need it for when they pay up to QualComm. Apple seems to have a losing Track record on legal issues ( maybe under performing would be better.). Cook should have gotten rid of Jackson ( after Cue) but maybe she knows where too many skeleton’s are in Apple’s closet.