As Apple begins a new year of operations, a media narrative is unfolding that Apple must ditch its reliance on premium hardware— and particularly iPhone— to desperately scramble its way into Services for the scraps left behind Netflix in a world of commodity devices. But the reality is actually a lot less dramatic for Apple, which has already proven an unusual ability to deftly adapt to changes in the industry. Compare its position today with that of Microsoft twenty years ago.

Lessons from Microsoft in succeeding and failure

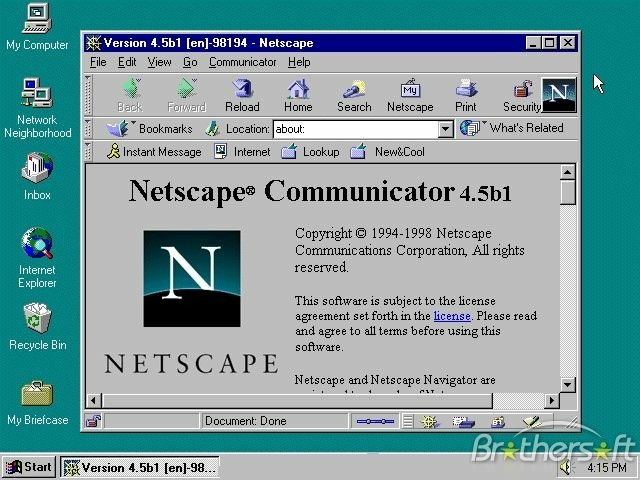

History is full of companies that either quickly corrected course to accommodate changes in the market, or drifted off into failure because they did not adapt. In the mid-1990s, Microsoft's then dominate Windows PC platform was challenged by Netscape, Java and other technologies that intended to make the World Wide Web an open platform offering a less restrictive, cheaper, decentralized alternative to Windows software.

Microsoft swiftly and radically changed its direction in response to the threat posed by Netscape Navigator. It used its existing position with Windows and Server to establish Internet Explorer as the de facto web browser, diverting much of the growing momentum behind Netscape and the open web to instead enrich its own Windows platform.

However, a decade later Microsoft was completely blindsided by Apple's iOS in phones and tablets. Additionally, Microsoft's parallel efforts to push into Google's search business largely failed. Today, Microsoft is enjoying more success in fighting Amazon for a slice of the enterprise cloud pie.

What made Microsoft successful— or not— in coping with various major transitions in tech might at first glance appear to be its leadership. However, a key factor in determining its level of success in navigating through a major market transition was also the quality of the technology it had available.

Netscape's goals in the 1990s were based on relatively simple web technology. Microsoft was able to acquire the same NCSA Mosaic browser code Netscape itself had sprung from to create its own IE browser. It then flexed its market muscle to tie IE into its existing Windows brand and platform in a way that was devastating to Netscape, a company that hadn't even yet figured out how it could competitively monetize its business.

However, a decade later Microsoft had no way to buy a copy of iOS. As Apple continued to rapidly build out its extremely profitable iPhone business, following up with 2010's similarly lucrative iPad, Microsoft was stuck with legacy Windows code tied to Intel processors— tech that was not competitive in either phones or tablets.

Efforts to build an "iOS-killer" from scratch (including Windows Phone and Windows RT) took far longer than anticipated. Neither could ultimately gain traction fast enough to derail the threat from Apple before iOS established itself as the commercial leader in enterprise and consumer mobility.

Microsoft couldn't buy iOS, so it burned through two years writing Windows RT while iPad took over the tablet market

Microsoft couldn't buy iOS, so it burned through two years writing Windows RT while iPad took over the tablet marketSimilarly, Microsoft's efforts to build or buy up search and surveillance technology to rival Google's wildly profitable, ad-supported online web services never managed to replace "Googling" with "Bing," despite massive, multibillion-dollar efforts by the company to diminish Google's position. The Windows and Mosaic technology that worked in the 1990s to keep the web tied to Windows PCs was not enough to keep Microsoft relevant in either mobile devices or in online search ads.

In cloud services, Microsoft's Azure is much better positioned to compete against Amazon and Google. That's resulted in a competitive market for cloud services that appears capable of supporting multiple successful companies. Investors today have assigned a high value to Microsoft despite the company having dropped the ball in mobile devices and search.

Yet, at no point did anyone seem to be concerned that Microsoft was making "most of its money" selling Windows licensing before it moved into applications and then servers and then cloud services.

Looking at Apple through the Microsoft lens

Apple naysayers like to suggest that the company is troubled because it relies on iPhone sales to make up most of its revenues. That's because smartphone sales overall are not rapidly growing anymore. It's also popular to say that the new markets Apple has built over the past decade, from tablets to wearables to home accessories to Services, are all "relatively nothing" compared to the company's $166.7 billion in annual iPhone revenues.

In reality, Apple's "other businesses" beyond iPhone and Mac currently amount to an additional $73.4 billion. That's nearly three times Apple's separate Mac operations that generate an additional $25 billion annually.

Add Apple's mostly new, post-iPhone businesses with the pre-iPhone Mac business it has maintained — and even grown despite about a 25 percent decrease in overall PC shipments over the last decade — and the total you get for Apple's non-iPhone business is significantly more than half the size of iPhone itself.

One can't say Apple's non-iPhone revenues are "nothing" unless they also say the same of Microsoft's or Google's entire revenues! Apple's $100 billion in annual revenues outside of iPhones is a gigantic operation, and the fact that such a massive business can be overshadowed by iPhone revenues says more about the scale of iPhone demand than of the "insignificance" of everything else Apple is doing.

Apple's largest and fastest growing new segment is Services, now a $37.2 billion enterprise annually that is growing faster than any of its hardware sales. But despite that parallel success, and the current weakness in the smartphone industry, Apple's iPhone revenues are not facing anything like the collapse of Microsoft's Windows licensing over the past decade.

That hasn't stopped some analysts from imagining a fantasy of iPhones being an imploding business that's melting under its own weight. Pundits also like to point to the examples of Blackberry and Nokia— both of which were once on top of the world in making mobile phones until demand for their products rapidly retreated into oblivion. Perhaps the same thing could occur to Apple!

But, that's really backward logic for multiple reasons. First, every marginally successful smartphone maker makes most of its revenues from smartphones. Samsung's IM Mobile division generates nearly zero profits outside of its smartphones sales, despite the fact that the group tries to sell a broader assortment of various other tablet, PC and wearable device hardware than Apple. Huawei, Lenovo, and BBK's Oppo, Vivo, and OnePlus brands clearly earn an overwhelming majority of their profits from phone sales because there simply isn't any comparable amount of money to be made in commodity tablets or PCs or other hardware.

In fact, the only companies that don't make most of their profits from phone hardware are the smartphone failures. If Amazon, Microsoft, Motorola, Nokia, or Google had been successful in challenging Apple's iPhones, they'd now be making most of their money from phone hardware too, simply because smartphones are a product that has been in high demand at prices capable of supporting large profits for many years now. Apple has simply capitalized upon that demand in a way that has been dramatically more successful than any other product category in the history of personal computing.

If Fire Phone hadn't flopped, would investors be mad most of Amazon's profits were coming from a smartphone?

If Fire Phone hadn't flopped, would investors be mad most of Amazon's profits were coming from a smartphone?Imagine if Jeff Bezos' Fire Phone hadn't been a flop. Would analysts be telling us that it was a big problem that all of Amazon's profits were now coming from sales of a successful new hardware product? It appears not. Even the Fire Phone's salvaged remains, which Amazon has used to power its Alexa service and loss leader Echo and Kindle Fire hardware, have been breathlessly praised despite accomplishing next to nothing for the company commercially or strategically and delivering a fat zero in profits, directly or through increased online sales.

Imagine if Microsoft's Windows Phone had taken off and the world had remained tethered to enterprise-demanded Windows, rather than being cracked open to consumer choice by BYOD policies. Would anyone be concerned that Microsoft was now making so much of its revenues and profits from smartphones, or that its acquisition of Nokia had worked out so well? No. The world of punditry is currently enthralled that Microsoft and Amazon are now each bringing in about $20-25 billion annually from cloud services. If they were earning Apple's $166.7 billion in iPhone revenues, would AWS and Azure be considered worthless because each is "only" about the size of Apple's Mac revenues?

Imagine if Motorola had been successful and had turned Google's $12.5 billion acquisition into a presciently strategic maneuver in stealing the smartphone business from Apple the way Android fans had hoped it would several years ago. Would anyone be upset that Google was earning far more from its global phone hardware than the $100 billion it currently brings in from mostly advertising revenues? They would not. And I bet the Wall Street Journal wouldn't be writing articles about how Google should just shut down its advertising and search business because they are 'so small in comparison.'

In 2015 Christopher Mims opined that Apple should "kill off the Mac," a business generating $25.5 billion in annual revenues

In 2015 Christopher Mims opined that Apple should "kill off the Mac," a business generating $25.5 billion in annual revenuesFear not for the company that can leap

The arrogant advice and troubling concerns that various pundits and analysts are voicing about Apple keep coming despite a solid track record of successfully navigating new transitions in tech. It seems beyond their grasp that Apple isn't just experiencing waves of luck that each manage to delay its imminent demise by a few more months.

The reality is that Apple was once relying on Macs to make the majority of its revenues, but when demand for Macs appeared to stop growing, it introduced iPod. Shortly afterward, the majority of its revenues were coming from personal audio devices. Eventually, it appeared that they wouldn't be growing anymore. That's when the company introduced iPhone. Nobody in pundit-land predicted iPod, and none saw any world-changing prospects for iPhone— until they became undeniable in retrospect.

Given that Apple has been the only company in the consumer electronics industry to deftly and successfully transition from one primary revenue source to the next, wouldn't it seem likely that if there is something that's about to replace iPhone, that Apple would probably be the one to do it?

Across the last few years, there have been two fronts in the War on iPhone: one being the ambitious replacement of smartphones with a futuristic AR/VR wearable along the lines of Google Glass or Microsoft Hololens or an advanced smartwatch wearable, the other being a more pedestrian replacement of Apple's aging iPhone with an all-new rival phone design featuring a full-face display with minimal bezel, typified by Andy Rubin's Essential phone. Yet both iPhone attack wings ran out of resources before they could take flight.

As they fell from the sky, Apple launched its own vision for the future: the Face ID driven iPhone X with a front facing depth camera tuned to make AR a selfie-focused feature of smartphones, rather than a premature replacement of the smartphone in the form of goggles. Apple had also successfully developed and deployed Apple Watch as the only successful watch product and moved on to AirPods before any other watchmaker or alternative wearable could gain any traction.

So Apple has trampled every potential iPhone replacement from companies big and small, while continuing to make— and radically modernize— its own iPhone. At the same time, it added Apple Watch and AirPods as significant new businesses that entrench rather than cannibalize its iPhone business. Why was Apple able to win every battle in the War on iPhone? It had to do with technology.

Leaping with what you know

In 2007, Steve Jobs announced that Apple Computer would change its name to simply Apple, Inc. in recognition of the fact that it was now building more than just conventional personal computers. That occurred just prior to the peak of iPod sales, right at the introduction of iPhone. But Apple didn't stop building Macs, and iPods didn't really go away; instead, the music player morphed into a software feature of iOS devices.

Additionally, iOS devices themselves were really a mobile-optimized version of Apple's Macs. Apple's ability to take its existing primary product category and technology portfolio and optimize it to serve a larger, broader market has consistently been key to its survival and dramatic growth.

Apple's ability and capacity to refashion its desktop Mac platform to power a new set of iOS mobile devices aimed at non-technical users wasn't a fluke. The fact that it took the company from sales of a few million Macs per year to the mass production of more than a quarter billion computing devices annually is also not a mistake or an intractable predicament, even if most of those devices are currently branded as "iPhones."

Peak iPhone is no more of an end for Apple than the apparent reaching of Peak Mac sales in 2001, or the Peak iPod occurring in 2008. The iPhone installed base will continue to grow, previous products will continue to expand or morph into new ones, and entirely new product categories will develop— we have more reason to believe that Apple will continue to deliver home runs than we have supporting the idea that Apple's failed competitors will whip up some surprise sauce that will turn any significant number of Apple's loyal customers into devoted buyers of a Pixel, Surface, Essential, MiPhone, Galaxy or a OnePlus.

Apple's adept ability to adapt its existing technologies is what enables it to keep winning these War on iPhone battles. So why do so many analysts and pundits express so much blind faith in companies that have repeatedly failed to beat Apple, and exercise such cynical doubt in Apple? They've been broadly saying that Apple was one mistake away from failure for a solid twenty years now. That's a long time to repeat the same incorrect prediction.

Apple's unique set of leaps

Apple's ability to leap to new product categories is particularly notable when you consider that other companies were wholly unable to make these leaps. Various PC makers, including the PC platform giant Microsoft itself, were unable to repurpose their existing PC technology portfolio into successful mobile devices despite far more years of trying, far greater initial resources to work with compared to the Apple of 2006, and broad industry participation. Pocket PC, UMPC tablets, Tablet PC, Windows Mobile, Slate PC, Zune, Windows Phone and Windows RT were all massive failures.

The open source community — partnered with such titans as Intel, Nokia and Samsung — also failed to successfully take desktop Linux into the mobile world. LiMo, Maemo, Moblin, MeeGo, Firefox OS, Sailfish, Tizen, KaiOS and Ubuntu Touch were all well-intentioned efforts that have really gone nowhere in either personal or enterprise mobile devices.

Google's Android wasn't based on an existing desktop platform, but rather on Sun's mobile Java ME middleware. Android makes use of the Linux kernel the same way Tivo did. But the Android application platform is not Linux; it's Dalvik byte code. And conversely, Google has been unable to successfully take its Android/DEX model into new computing form factors including tablets, media devices, game consoles or wearables despite a decade of intense but ultimately failed efforts.

Apple's mature Mac development frameworks and scalable operating system gave the company the ability to rapidly innovate its way into a smartphone market that was thought to be essentially impossible to enter due to the competitive threats of so many large, entrenched rivals. On the other hand, Android merely replaced licensed platforms like Symbian, Java ME, and Windows Mobile with software that was free.

The companies that couldn't compete with iPhone using those earlier platforms (including Blackberry and Nokia) are not harbingers of Apple's upcoming fate. Instead, they foreshadow today's set of companies making use of the Android platform, which is similarly just "good enough" for today's smartphones but lacks the capacity to successfully support what's next. iOS, on the other hand, has already successfully created massively new businesses in tablets, home appliances, and wearables— even as the original Mac is still generating leading profits in the conventional PC space.

Android is still shipping on lots of units, just as Java was once shipping on lots of units from Nokia and Blackberry. But in both cases, the underlying technology is not creating successful new products the way Apple has spawned multiple, multibillion-dollar new product categories from iPad to Apple Watch to AirPods.

Apple lept from Mac to iPhone, then brought its iOS experience to iPad, vast leaps no other platform has successfully made

Apple lept from Mac to iPhone, then brought its iOS experience to iPad, vast leaps no other platform has successfully madeThe Mobile Mac

The fact that Apple called its product iPhone and not "Mac Mobile" created an arbitrary boundary in many people's minds that the two were unrelated. But in reality, iPhone was as closely related to the Mac as a mobile device and desktop PC could be, albeit using a new set of interface guidelines, policies and design changes imposed to make it successful as a mobile device for the mass market.

In comparison, Microsoft's own "Windows Mobile" was radically different from its desktop Windows in virtually every technical respect apart from carrying forward the same old PC desktop interface, its software market with no security for users or developers, and its other legacy ties to the 1990s PC world that held it back.

So from the 2000's past to the recent present of the 2010s, Apple has proven capable of exercising its rapidly lithe, innovating ability to take its existing technologies and create new computing forms that retain its influence over the most commercially successful and strategically important markets— not through monopoly licensing but by making the products that most people want to pay a premium for. That winning strategy of the past also appears to be the best suited for the future.

Consider Apple's future in PCs and iPhone, detailed in the next two segments of this series.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

39 Comments

A lot of the "doom-and-gloom" surrounding Apple is nothing more than social media drama deliberately created. Apple will push the boundaries of what we consider as personal computers. John Srouji is doing great work hardware-wise when it comes to Apple Ax chipset. The only thing Apple has to do is keep evolving iOS into a more robust mobile operating system and unlock more features that we know it can handle. I really look forward to a day when I can do all the work I would usually do on my PC right on my iPhone XS Max or iPad.

It is always a question of expectations. For some, “surviving” means literally not going out of business, for others, it means being profitable, and for others again to maintain the most valuable brand etc.

Will Apple remain on the top of market cap, perceived as innovative, market share in certain markets? Maybe. Likely not forever. Actually, I think that the next number one companies for the time to come in terms of market cap will be Facebook and amazon - whether I like it, or not. Would that fact as such render Apple any less meaningful, or “good”? Exactly. It wouldn’t.

This article does not provide any support for its premise that "a media narrative is unfolding that Apple must ditch its reliance on premium hardware." The only article it cites, the Mims article, argues that Apple should shift its focus from Mac to iPhone, iPad, and other consumer products (not services). The Mims article even suggests against a shift to services, noting the failure of Apple's contemporaries to capitalize on a services shift, and that Apple's "traditional weakness . . . is cloud services."

Apple has been the one pushing the services story, and working to shift the focus of investors from hardware to services, which has included discontinuation of reporting unit hardware sales. Whether Apple can successfully pivot to services remains to be seen, but based on Apple's previous efforts in the services arena, the odds are not great.

Apple is a great hardware company, but its services offering have not been good at all. Even its operating systems have started to become bloated, with security issues and bugs occurring at higher rate than ever before. Those of us who used iOS and MacOS in the mid to late 2000s remember a time where bugs were a rare occurrence.

While there may be some publication out there that has asserted that Apple must shift away from hardware, the consensus is more an expression of doubt as to whether can pull off a shift to services, rather than a united call for Apple to shift to services as this article alleges.

The real consensus in the media is that Apple must continue to focus on making great hardware, while monetizing that hardware through services.

Excellent article, as usual. Thanks