Law enforcement agencies are taking advantage of Google's collection of location data generated by its iOS apps and Android devices to determine potential suspects of crimes, an investigation into the practice reveals, but the misuse of a database has led to innocent iPhone users being dragged into cases just from being relatively nearby to an area of interest.

Google is well known for its data collection activities, which it primarily uses to serve advertising to its users, but the harvesting of location data has become what is considered an invaluable tool for law enforcement officials to search for perpetrators of crimes. Equipped with a warrant, requests can be made to Google that could lead to the identification of people who were in an area at the time of an event, with the criminal potentially in that group.

Despite the potential of a privacy-infringing database, an investigation by the New York Times suggests the potential for false positives, or simply misidentification, could cause innocent parties to be accused of crimes despite not being aware of them taking place.

An example given in the report is that of a murder investigation in Phoenix, where suspect Jorge Molina was questioned in December about his whereabouts nine months prior. Molina was summoned due to his mobile device coming up in a list from a Google-targeted search warrant for location data, as well as some elements of his life matching up with circumstantial elements.

After spending nearly a week in jail, Molina was released after investigators discovered new data, which led to the arrest of his mother's ex-boyfriend. It was found the boyfriend had sometimes used Molina's car.

Despite being innocent, the arrest at his place of work led to Molina losing his job. Molina's misfortune didn't stop there as his car, which was impounded for the investigation, was then repossessed.

After the first use of the technique by federal agents in 2016, and initially reported in 2018 based on its use in North Carolina. After its usage in that state, law enforcement in California, Florida, Minnesota, and Washington are also issuing warrants to Google for data, with the practice reportedly rising to as many as 180 requests in a week.

The database, known to Google employees as Sensorvault, contains the location records of "hundreds of millions of devices worldwide." The database also holds records on a historical basis, with some data almost a decade old.

The warrants themselves as known as "geofence warrants, as they define an area and a period of time that is of interest to law enforcement officials. Google scans records for devices in the area, applies an anonymous ID to the data, and passes it over to investigators.

After examination of the data's locations and movement patterns, suspicious ID numbers are sent back to Google for more information about those particular devices, including user names and other data that may be beneficial to the investigation.

In a statement, Google director of law enforcement and information security Richard Salgado advised the search company tries to "vigorously protect the privacy of our users while supporting the important work of law enforcement, and that it only hands over identifiable information only "where legally required."

While potentially valuable, the rise in requests has caused the Google team working on the database to have trouble keeping up, to the point that it can take "weeks or months" for law enforcement to receive a response. In one 2018 case in Arizona involving a spate of bombings, police received the data six months after receiving the warrant.

Even though it can take time for data to pop out, the request is still a prized data trove to police. Brooklyn Park, Minn. Deputy Police Chief Mark Bruley declared "It shows the whole pattern of life," in that it reveals how people go about their business every day, including when and where they go. "That's the game changer for law enforcement," added Bruley.

Investigators advised to the report that they made requests to Google only, and did not provide such geofence warrants to other firms. Even so, the ubiquity of Google's services may mean law enforcement only needs to ask the search company its requests.

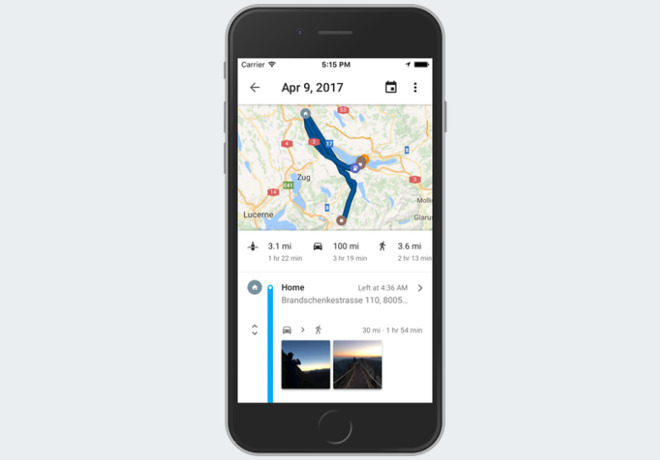

Apple has advised law enforcement that it does not have the ability to provide such location data, as it does not keep it, which is in line with the iPhone maker's long-held and public policy of holding minimal data on its users, and anonymizing it where possible. Despite this policy, Google's apps are still able to collect enough data to effectively make iPhones traceable under Google's system.

Even so, iPhone users may have less data collected in general. One trial in August 2018 revealed idle Android devices could send nearly ten times as much data to Google than iOS devices do to Apple's servers. It was however suggested in the study that location data accounted for 35 percent of all traffic back to Google.

Intelligence analyst Aaron Edens of the San Mateo County sheriff's office explained that, in the data of hundreds of phones seen by him in his work, most Android devices and some iPhones he had seen had provided the trackable data to Google.

While the potential for false positives and the long delay for results are issues, current and former Google employees say that there are other problems making Sensorvault unfit for the job. The database wasn't designed for the needs of law enforcement at all, and served a different purpose at the company.

The cache is also somewhat unreliable as not every mobile device's data is collected within it, meaning not all potential suspects are showing up in results. There is also the issue that, while location data may be recorded every few minutes, the timing and location of each recording may not necessarily correlate with where and when a crime took place.

The practice is also questionable on a legal standpoint, as privacy is a concern in some instances, suggests University of Southern California law professor Orin Kerr. For example, while the data of innocent people may be collected for cases, not every state keeps the information sealed.

One Minnesota case involved the release of the name of an innocent party, identified in a police report because he was within 170 feet of a burglary. A local journalist contacted the man, who was surprised by his identification, and it turned out was probably in the area due to his job as a cabdriver.

There is also the question of whether it is constitutionally sound to perform such searches, as the Fourth Amendment dictates a warrant must be limited in scope and establish probable cause that evidence will be discovered.

A review of warrants showed the range of searchers varied from a single building to multiple blocks in size, but while most only covered a few hours in time, some instances requested data spanning across a week.

While a Supreme Court ruling in 2018 decided a warrant was required for historical location data over weeks, the ruling did not seem to answer the legitimacy of geofenced searches. Google itself determined it should require warrants for the requests before the ruling, as well as producing the anonymous data procedure in-house.

There is also a question mark over whether there should be multi-step warrants, with one covering the initial anonymous data request and another for specific ID numbers. Depending on the jurisdiction, an investigator may be required to return to a judge in order to acquire the identifiable data, which can extend to include the contents of emails and months of location patterns.

Google's location data collection has come under fire from its critics numerous times, such as the revelation in August the company's data collection policies permitted the collection of location data even if a global "Location History" setting was disabled on an account. Not long after the discovery, Google was quickly slapped with a class action lawsuit over the constant tracking, under the claim it breached the user's privacy.

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

-m.jpg)

6 Comments

Let's say I don't use any Google's apps not even Google Maps. Google still collects geolocation through Safari and other apps that use Google Ads, which is tied in to Google analytics that carries geolocation data?

So, WHICH of the b****y google apps on the iPHONE/iPAD pass data on ?

Certainly only the ones that you allow access to location data.

Google Maps exited my life the day Apple Maps came online (and I haven’t missed it). TIme to delete Google Assistant as well. Everything else Google might touch is behind a VPN or doesn’t require location data, so they’re not getting much from me. Feels good.