Apple pursued AR as a way to sell premium hardware and to attract developers to iOS. Here's why Apple's AR vision uniquely succeeded despite opposition, naysaying, and competitive ideas — and why Google and its Android partners failed to do the same with smartphone VR.

The unexpected, 5 year failure of smartphone VR

As detailed in the previous segment, the concept of smartphone-based VR— introduced by Google's 2014 Cardboard initiative— was once widely hailed by the tech media as being the "next big thing" in mobile. Cardboard grew into Android's Daydream VR and induced parallel development by Samsung and Facebook to support the more sophisticated Gear VR platform.

Yet within just five years, Google, Samsung, Facebook, and everyone else who jumped on the 'cardboard bandwagon' of smartphone-based VR abandoned their efforts and dumped support for customers who bought their handset VR products. Along the way, none of those involved earned any significant profits from smartphone VR.

Various VR efforts also failed to drive significant numbers of buyers toward premium smartphone hardware. Instead, Google's VR-ready Pixel phones only languished along as a hobby-flop.

Unit sales of Samsung's upscale, Gear VR-compatible Galaxy flagships and phablets also slid sideways as the company publicly refocused instead on promoting sales of its cheaper midrange A-series phones.

Phone-based VR ended up an embarrassing, unmitigated commercial disaster worse than even 3DTV or 3D smartphones. With few exceptions, tech media writers and analysts of the mid-2010s completely failed to predict how badly VR would serve the mobile industry and its investors.

The unanticipated success of smartphone AR

While tech media personalities overwhelmingly cheered on phone-based VR right up until it was abandoned by its main proponents last year, there was less excitement and more scrutiny of AR, particularly of Apple's.

That's somewhat remarkable, because Google, Samsung, and Facebook had all failed at quite a lot of their initiatives in mobile— particularly in new hardware— while Apple had maintained a solid track record of consistently delivering hardware hits, with only a rare few misses with minor initiatives such as iTunes Ping and iAd.

By 2016, Apple's chief executive Tim Cook was regularly taking the rather unusual step of confidently commenting on the future prospects of unreleased technology, frequently sharing his take on AR and VR in at least general terms. That August, Cook told the Washington Post that he thought augmented reality was "extremely interesting and sort of a core technology."

In September, Cook said in an interview with ABC News, "there's virtual reality and there's augmented reality— both of these are incredibly interesting, but my own view is that augmented reality is the larger of the two, probably by far."

In October, Cook again touted the benefits of AR over VR, stating "There's no substitute for human contact, and so you want the technology to encourage that."

The next February, Cook again contrasted the two technologies in an interview with The Independent, stating that headset VR by nature only had a niche appeal because it "closes the world out" in a disassociated experience, while stating that AR as a core technology promised to broadly benefit a much wider audience.

Cook even claimed that AR could be as big of an opportunity as the smartphone itself had been. "I think AR is that big, it's huge," Cook said. "I get excited because of the things that could be done that could improve a lot of lives— and be entertaining."

Cook's unpopular take on AR

Cook's depiction of the relative merits of AR and VR as technologies as perceived within Apple was effectively the opposite of most other firms. Facebook and its content partners saw the development of VR experiences as the big opportunity, with less appreciation for what AR might deliver.

Without its own successful phone OS platform, Samsung similarly bet big on VR because it could deliver Galaxy VR hardware on its own. To deliver an AR phone product, Samsung would have to coordinate closely with Google, deferring to its leadership of Android as a platform.

That's something Samsung had soured on after its 2011 Galaxy Nexus collaboration with Google. Samsung had even attempted to launch Tizen as its own OS to replace Android in 2012, and by 2014 was using Tizen to power its Galaxy Gear watch. A year later it used Tizen, not Android, to power its smart TVs.

It wasn't looking to expand its dependence on Google's Android in future hardware, which helped blunt any interest in AR collaboration.

Microsoft similarly had no successful mobile platform to use in promoting AR like Apple. It had launched HoloLens as a standalone project to deliver various technologies related to AR and VR. However, HoloLens remained so isolated from reality and the consumer market that Microsoft didn't have to take any coherent, strategic stand the way Cook had been with AR.

Microsoft could promise everything while delivering very little. It even rebranded the world around it by referring to various technologies as "Mixed Reality."

So a large part of the reason Apple was on its own in touting AR was that it was the only company capable of delivering it on a large scale in a way that could have a significant commercial impact. While some sort of VR was possible even at the facile level of Cardboard, delivering functional AR would require a much greater and more sophisticated jump in technology, along with tight integration between various hardware and software layers.

VR presents the user with an immersive experience of computer-generated graphics that are wrapped around them. AR requires additional technology to convincingly anchor a virtual world on top of the existing world. "Augmented reality" is literally an augmentation of reality with the virtual, so VR is effectively a subset of AR technologies.

But that's not how many in the tech industry have viewed it. Instead, pundits and analysts often spoke of VR as an obviously exciting technology that was easy to demonstrate, while speaking of AR as if it were a less impressive concept that would be harder to sell to consumers as valuable and desirable.

Google, however, did know this. In 2014 it began publicly working in both fields: alongside its Cardboard VR project that had originated as an employee's side project, the company also launched Project Tango, its independent effort to develop an AR platform. Tango originated within Google's advanced technology labs as a serious research project, not as a mere side hobby.

Both Cardboard/Daydream VR and Tango AR continued at Google over the next few years with participation from various Android partners, but neither resulted in much more beyond small scale, experimental tinkering. Google's Tango was first to market with many parts of the AR technology puzzle but failed to convert its advantage into a salable product.

Apple sneaks out AR to the masses

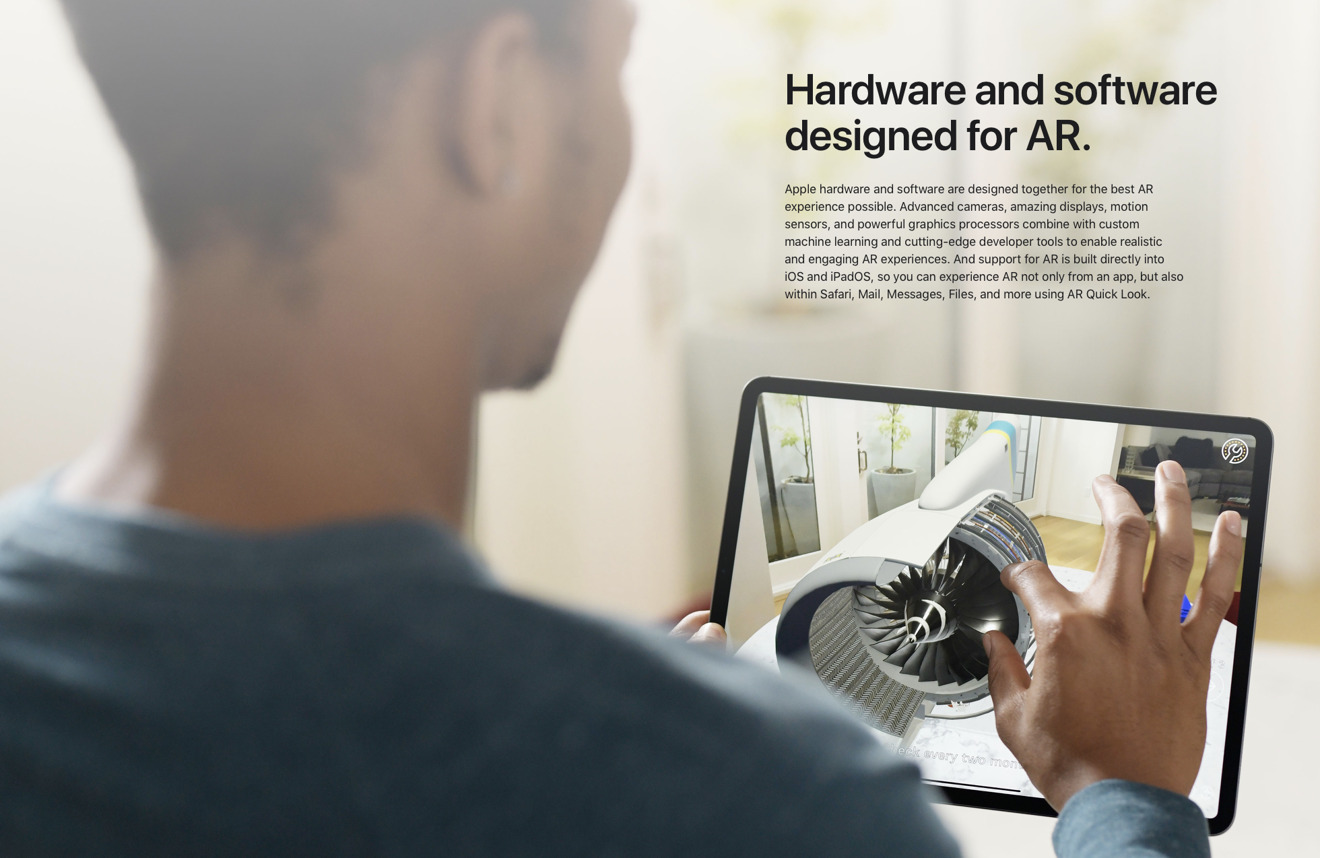

Three years after Google floated out Tango, Apple unveiled ARKit at WWDC17, opening up its new AR platform to developers with an addressable installed base of hundreds of millions of iOS 11 users. It could immediately boast that it had launched the world's largest AR platform. Later that year, it launched the new $999 iPhone X and iPhone 8 Plus, both of which featured the company's new Portrait Lighting effects.

Over the three years since, however, pundits and analysts have largely failed to grasp what was going on. This March, Lucas Matney penned a puzzling, dismal take on the prospects of Apple's AR in a TechCrunch article titled, "Can Apple keep the AR industry alive?"

As clickbait generators worried about Apple "keeping AR alive," developers like IKEA deployed commercially relevant AR apps

As clickbait generators worried about Apple "keeping AR alive," developers like IKEA deployed commercially relevant AR appsIt suggested that the only thing behind AR was "Apple's enthusiasm," stating that "the company's ARKit development platform has brought out some interesting use cases, but app developers have scored few resounding victories." The TechCrunch piece complained that Apple has "been slow to bring AR functionality into its own stock apps" and that "consumers just don't see anything they want yet."

That was not an unpopular opinion. Many industry observers seem to think that the only AR application Apple has launched to date has been Measure, the app that uses ARKit's Visual Inertial Odometry to estimate the dimensions of real-world objects. And of course, while being criticized for delivering ARKit as a platform that largely delegates AR app development to third parties, Apple also caught flack for daring to release Measure because it infringed upon the potential of third parties to sell their own AR measuring apps.

The alternative reality of the tech media

Yet between 2017 and 2020, Apple sold hundreds of millions of its high-end iPhones— every year— at an average selling price of nearly $800. The most popular iPhone of 2018 was Apple's new iPhone X, followed by its iPhone XR replacement the next year and then iPhone 11 this year. On top, Apple was also selling millions of ultra-premium iPhone XS and then iPhone 11 Pro models, also in volumes no other Android maker was even coming close to selling with their own premium-priced flagships.

Year after year, Apple inhaled virtually all of the revenues from high-end phones, augmenting its profits on a scale no other handset company could touch. Something was magically separating iPhones from commodity Androids.

Beyond Apple's brand and reputation, it appeared to be the App Store and iOS, although pundits were insisting that apps didn't matter either. They explained that Android had plenty of apps and claimed that in China nobody even used apps anymore because of WeChat.

Pundits were so out of answers on why Apple was still in business that they began to announce that the reality everyone was observing was simply wrong. The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, and Japan's Nikkei Asian Review all regularly reported to their audiences that iPhone X was a "disappointing," "overpriced" product with "weak" sales, and that consumers were certainly not excited about it at all.

This bizarrely continued the next year, when Yoko Kubota and Joanna Stern of the Wall Street Journal portrayed Apple's very popular iPhone XR as "The Phone That's Failing Apple" and "The Best iPhone Apple Can't Sell."

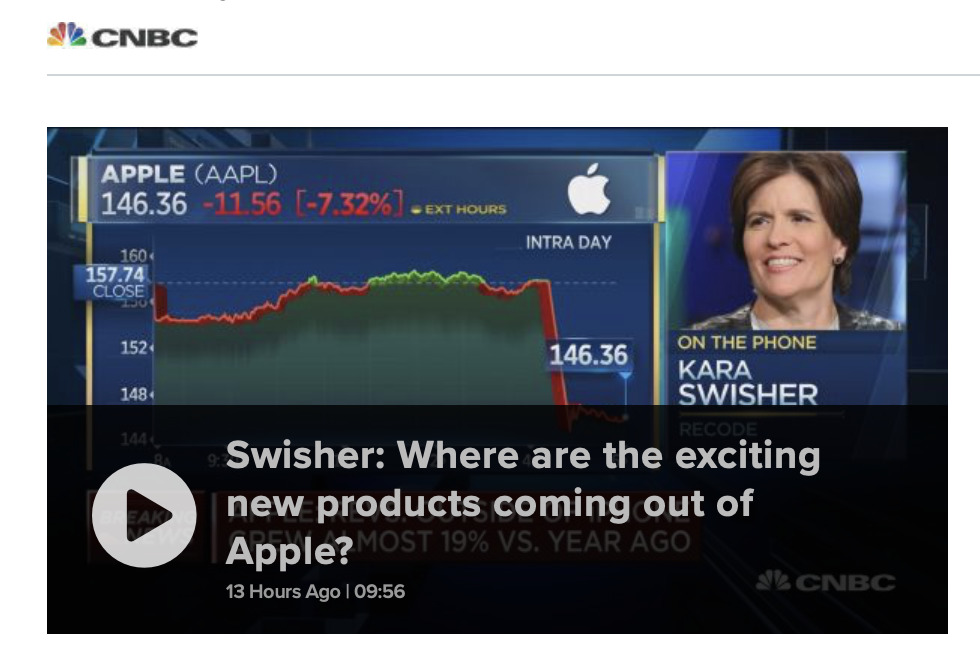

At the same time, Kara Swisher of Recode appeared on CNBC to advance the idea that Apple's had an "innovation problem," stating that "the innovation cycle has slowed down at Apple. Where is their exciting new product, and where are their exciting new entrepreneurs within that company?"

The most bizarre thing was that these journalists well all very much well aware of the "exciting" products Apple was introducing and the talent that the company was recruiting. They were being invited to Apple's events, being handed simple technology overviews, and were even writing about Apple's notable AR-related hires in parallel.

In 2017, Mark Gurman wrote a report for Bloomberg detailing various industry researchers that Apple had recruited to work on AR under the title "Apple's Next Big Thing: Augmented Reality."

All of these journalists should have grasped the power of AR. After all, they were all augmenting reality with their own fantasy virtual world they had created on their computers and projected into the views of their audiences.

AR Software Sells Systems

Certainly the preference for Apple's iPhones among affluent buyers, even at a significant price premium, has been the result of a lot of factors. But one notable feature driving sales of Apple's best iPhones over the past three years was the very thing that TechCrunch just recently claimed to be a slow, struggling effort with an uncertain future: AR.

Computational photography is undoubtedly driving high-end smartphone sales; the ability to take flattering selfies and portraits is extremely popular among buyers. Apple's most notable camera feature of 2017 was Portrait Lighting, along with iPhone X's new TrueDepth effects that enabled photorealistic effects in third party apps such as Snapchat.

Both of these are actually examples of AR, developed using Apple's ARKit development tools.

So rather than rolling out AR and ineffectually pawing at it for five years without accomplishing anything, Apple delivered attractive features using AR that immediately helped it sell its most expensive iPhone ever to enthusiastic audiences globally— before the public realized it was even using AR.

Note that this occurred the same year that Samsung was struggling to sell its Galaxy S9 with or without Gear VR, after four generations of Gear VR trying to establish some reason for Android buyers to opt for Samsung, and specifically one of its higher-end models.

Cook had been right: AR was already having an immediate and significant impact on smartphones in a way that phone-based VR had failed to achieve across years of trying. And while John Carmack of Facebook's Oculus group outlined in retrospect that the friction of using Gear VR had kept smartphone users from staying engaged with VR experiences more than a couple of times on average, the simple and attractive benefits of features like Portrait Lighting were being regularly used on iPhones.

AR helped to contribute toward Apple's computational photography features in a way that blunted Google's pointed attack in pushing its own sophisticated AI-driven camera features on its Pixel phones. That gave Apple the ability to match and improve upon Google's own innovative night mode feature before Google could copy Apple's AR-based Portrait Lighting features.

This is even more remarkable when you consider that Google had been working on its own version of AR in public, with industry collaborations, for several years before Apple introduced Portrait Lighting or its ARKit development tools.

And rather than being ignored by third-party developers as TechCrunch implied, Apple's ARKit has enabled significant new opportunities ranging from video games to enterprise markets, with particular success stories in education and in online retail. Last year at WWDC19, Apple's ARKit 3.0 brought Microsoft on stage to demonstrate Minecraft Earth playing in AR with the new People Occlusion feature.

Apple effectively used AR to bolster its sales of high-end iPhones at a time when it was ostensibly "common sense" that nobody would pay $999 for a phone, and certainly not when there were cheap Androids available. Cook also rather masterfully positioned AR as his personal vision and successfully delivered a massive home run with AR even as his leading rivals failed to do much with AR, "Mixed Reality" or VR. Apple's work has also embarrassed pundits and analysts who tried to advance their careers by portraying the company as having "run out of innovation."

But Apple's long term, focused investments in AR have also accomplished something else, as the next segment will detail.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

32 Comments

I don't know that AR is really any more popular than VR... I've seen much more hype about AR than VR. I think AR is probably more useful, but VR is more impressive so gets more press coverage. In any case both are pretty cool, but I am yet to see a particularly compelling AR app that has me coming back for more. It's more a tech demo of "look what this does", never to be used again.

I hadn’t seen that AR was already something that I was using. But to put it more simple, Apple has the (money)power to play the long game. And that is apparently needed to realize a truly working business case, where AR is broadly adopted as enhancing the way we look at things.

Also not really sure where DED gets the idea that the portrait modes on iOS are AR, they use AI to do their job, but not AR. The link takes you to AppleInsider's AR page, which only mentions AR in the context of using the lidar sensor for better 3D maps.