Few things have drawn more attention to police brutality incidents than the unflinching eye of smartphones — with the iPhone in particular leading the way.

The ability of smartphones to capture and broadcast shocking images in real-time has increasingly focused attention on a longstanding problem of police brutality in America. Here's a look at why smartphones were needed to bring attention to the problem, along with Apple's complex role in both supporting police and in drawing attention to underlying problems in conduct among police officers.

Protection of businesses and property

Smartphones and other advanced technology likely wouldn't even exist without police serving to protect businesses from pirates, thieves, and other criminal elements. Apple employs its own security but also relies on the police when its retail stores are attacked by looters, robbers, or scam artists.

Originally, serving guard duty in a private policing force was seen as a thankless, undesirable job. The modern concept of a professional, public police force is "a relatively modern invention" first established in Boston in 1838 by shipping merchants seeking to transfer the expense of private security to the public as a socialized police force serving the "collective good," as noted by Olivia Waxman for Time

Initially, police largely served the interests of businessmen and elected politicians, who both paid their salaries and gave them the power to maintain "law and order" in a way that benefitted the affluent voting majority. That power was often flexed to marginalize and repress religious or ethnic minorities, as well as workers protesting for better working conditions. Brutal repressions of efforts to organize labor unions were common in the U.S. as business interests used the police to protect their profits.

Because local political parties typically appointed police captains, they too had the expectation of using the police to intimidate voters and collect bribes that would enable their political machine to remain in power. Into the early 1900s, American police often effectively acted as mafia for crooked commercial interests. During the Prohibition Era, politicized police groups routinely demanded protection money to look the other way for speakeasy operators.

It wasn't until 1929 that the ineffectiveness of law enforcement was scrutinized by President Hoover's appointment of the Wickersham Commission, resulting in efforts to divorce police precincts from the boundaries of political wards in order to minimize influence. But there was also another serious problem that had developed under the political influence of police: racism. This was often expressed in the brutal treatment of Blacks and other minorities, as documented by Smithsonian Magazine.

While police in urban centers of the northern United States had initially been established to protect shipping ports and businesses and crack down on drinking and prostitution, in the South, police militias had largely been organized to enforce the institution of slavery. Slave patrols in the early 1700s chased down people fleeing slavery and protected plantations from uprisings. After the Civil War, "many local sheriffs functioned in a way analogous to the earlier slave patrols, enforcing segregation and the disenfranchisement of freed slaves," Waxman wrote.

As police agencies began to professionalize over the last century, the problem of racism continued to grow as white majorities established laws and informal rules designed to maintain segregation. Even in states like California that lacked the South's history of slavery, it was commonplace for housing developments to restrict ownership by race under housing covenants that continued well into the 1960s. Black families routinely faced the threat of having their houses burned to the ground. Public policies including the construction of freeways commonly destroyed Black neighborhoods.

The birthplace of personal computing in California's Silicon Valley was shaped by racist policies that restricted who could live in specific neighborhoods. Yet the products developed there would eventually help to facilitate a shift in thinking and bring attention to longstanding racial problems.

Low cost entertainment

The effective segregation in California and much of the rest of the United States helped distract attention away from underlying race issues. The barriers that intentionally kept affluent areas white also often prevented those populations from seeing the realities of police brutality that often focused on communities of Black, indigenous, and other people of color.

One of those barriers was the reporting of violent police actions by members of the media who often based their narratives on official police accounts. Black newspapers that documented police violence against citizens across the first half of the century rarely reached white audiences.

Instead, mainstream audiences were presented with entertainment that presented narrow stereotypes of Blacks as criminals. In 1989, Fox began airing Cops, a cheap to produce show which presented edited footage of arrests that consistently presented police officers in a positive light and normalized the often rough treatment of the accused. Two decades later, it became the longest-running series on the network, while depicting only flattering portrayals of police to avoid any risk of losing access to the cameramen riding along with active duty police.

In 1991, an independent video camera recording from a balcony in Los Angeles captured a different portrayal of police conduct in the violent beating of Rodney King. That videotape sparked outrage, particularly after the police involved were tried on charges of police brutality but then acquitted. Subsequent riots resulted in dozens of deaths and extensive property damage. But without access to record continuous cases of similar law enforcement brutality during arrests or within jails and prisons, the positively spun presentation of entertainment shows like Cops continued to present a one-sided portrayal of police activity that only ever demonized the accused.

On its own, television failed to present the reality of racism in policing because accounts of police violence were often edited and filtered by journalists seeking to maintain a good relationship with police sources, who were allowed to shape the narratives being presented. That began to change when video cameras moved from bulky professional equipment into mobile devices.

Eye Phone

When Steve Jobs introduced iPhone in 2007, the new device was described as "an iPod, a phone, and an Internet communicator," all in one device. Although it could snap basic photos, it wasn't much of a camera and couldn't even record video at all. Yet over the next few years of rapid enhancements, Apple increasingly invested in improving its camera and making photography central to its marketing and ongoing development.

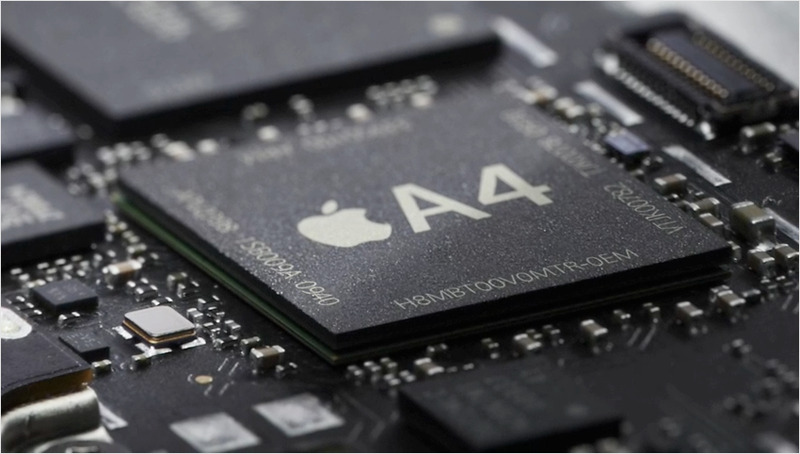

Apple's first custom mobile chip, A4, included a dedicated, custom image signal processor that turned 2010's iPhone 4 into a competitive point and shoot camera. Jobs even compared its form and styling to "a beautiful old Leica camera." Beyond simply taking photos and capturing video, iPhones packed in the processing power, memory, and networking required to share images instantly.

Various cameraphones had already existed for many years, but a distinguishing characteristic unique to iPhones was Apple's model of unlimited WiFi networking, along with the iMessage service it introduced in 2011. Unlike existing SMS and MMS 'picture messaging,' Apple developed iMessage as a way to allow users to send photos and videos without cost. Most mobile carriers were still trying to charge per-photo message fees, and some, including Verizon Wireless, even tuned off phones' mobile WiFi features to force users to slowly sync all of their data over the 3G mobile network so they could charge users per-minute networking rates.

Apple's iPhone effectively converted basic cellular telephones from "good enough, carrier friendly" devices offered for free by mobile carriers into a new class of powerful iOS devices that could share images and videos as freely as a desktop computer. Apple's "revolutionary" design of the premium, powerful iPhone rapidly turned the company into the world's most valuable tech company, while raising the minimum expectation of cellular phones and democratizing access to mobile-connected cameras that could instantly broadcast videos across social networks.

The original, fee-based cameraphone model optimized to serve mobile carriers quickly evaporated. Samsung, Google, and other Android partners were incentivized to shift their initial plans for simple phones offered through— and restricted by— mobile carriers into devices designed to work almost identically to iPhones. As a result, powerful phones with advanced cameras quickly became available to virtually everyone at affordable prices.

That meant that anyone could record what was going on, and broadly share their first-hand experience unfiltered to wide audiences.

Black Lives Matter

In 2014, smartphone footage depicting police killing Eric Garner in Staten Island using a lethal chokehold in an arrest related to selling untaxed cigarettes brought new attention to the use of excessive force. Without the "I can't breathe" video of Garner's death, the public would likely have never heard of the incident. Further, the fact that the officer who choked him to death was never indicted caused reporters to rethink the nature of the system that would allow such a killing to take place without any consequences.

The next year, Walter Scott was killed in a police shooting following a traffic stop over a broken brake light in South Carolina. Initial media reports echoed police statements that claimed Scott was shot only after taking the officer's stun gun away and threatening to use it, and that officers attempted to perform CPR on Scott afterward. But then smartphone footage of the incident appeared showing that was not true. The video revealed that the officer rapidly unloaded his gun into Scott, then handcuffed him face down and didn't even attempt CPR. The story rapidly escalated to national news, further revealing the vast difference between official police accounts and reality.

Smartphone video of Walter Scott being shot and left to die face down challenged the offical police account

Smartphone video of Walter Scott being shot and left to die face down challenged the offical police accountIn 2016 Philando Castile was pulled over in Minnesota, also for a traffic stop. The officer approached and immediately shot Castile seven times. The driver's traumatized girlfriend streamed the aftermath of the shooting from her smartphone via Facebook, which subsequently depicted officers arresting her while failing to offer any medical attention to Castile even as he sat dying. Instead, other officers comforted the officer involved in the shooting.

A regular series of similar shootings by active-duty police, by off duty police, and by citizens pretending to be police — often recorded by smartphones — have established unmistakable patterns of brutality often targeting minorities far out of proportion to their population. Efforts to draw attention to and address the causes of such events by groups such as Black Lives Matter have often been met with ridicule and the defense of law enforcement regardless of the circumstances.

BLM has also directed attention to lethal excessive force against whites by police, and to the violent, military-style attacks on protests against police brutality commonly directed against minorities, occurring in stark contrast to how police routinely exercise restraint when dealing with armed, anti-government protestors who are white.

This year's rapid shift from coverage of COVID-19 lockdown protestors confidently marching with guns into the Michigan statehouse in April, followed by the recent violent crackdown on unarmed protests against police brutality— as well as police attacks on journalists and medics — were all captured by smartphone users, creating evidence of unequal treatment that is impossible to ignore.

International audiences watching the treatment of civilians protesting police brutality in the United States are increasingly seeing conditions as being just as bad as China's attacks on citizen protests in Hong Kong and elsewhere. And in both countries, Apple faces the difficult task of working with governments and police to help solve crimes, stop fraud, investigate thefts, and secure users' privacy, while also facing the reality that those same governments are demanding dangerous encryption backdoors and other unconscionable requests to continue cooperation.

Ultimately, we have to demand and create a material change in how our fellow citizens are treated.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Bon Adamson

Bon Adamson

-m.jpg)

6 Comments

Very well said. Thank you.

*Applause*

Thanks DED for this article, I have often told people that BLM would not exist without the technology of the smart phone and particularly the advent of the iPhone. Thanks too for the historical perspective on policing as well. It reminded me about the book by Mike Davis, City of Quartz. In that book he puts forth the argument that the LAPD existed first and foremost to patrol black neighborhoods and contain them.

I am becoming aware that 2nd amendment beliefs are similar to attitudes on polcing in our country. The California laws on open carry were a direct result of Black Panthers carrying guns and Republican fear and not because of “liberal do-goodism” an obvious double standard.

We have to get control of partisanism and tribalism in this nation and find a new civic order.

“Few things have drawn more attention to police brutality incidents than the unflinching eye of smartphones -- with the iPhone in particular leading the way”.

How does one determine that from an online video?