The $69.3 million sale of digital artwork using non-fungible tokens — or NFT — has generated interest in the relatively new technology. Here's what you need to know about what the tokens are, and how they are being used to bring digital art sale dollars in line with paintings and sculptures.

On March 11, auction house Christie's sold a lot from artist Mike Winkelmann, known as "Beeple," for $69.3 million. As Christie's is a major auctioneer that deals with highly valuable art, this isn't out of the ordinary until you realize that the sale wasn't for a traditional artwork.

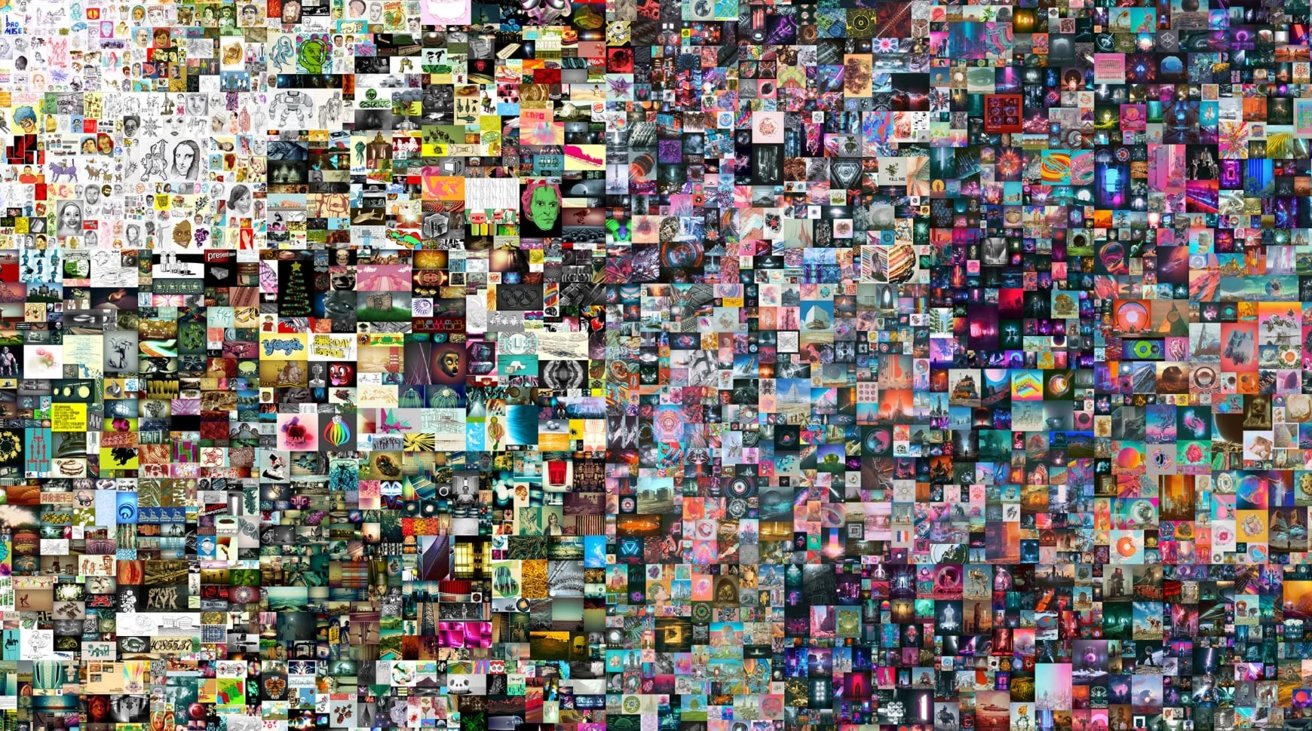

The sale of "Everydays - The First 5,000 Days" is claimed to be the first for a purely digital work of art via a major auction house. A collage of Beeple's daily digital art production, the work shows the artist's progression over multiple years, including changes in technique and style.

The auction winner was identified as "Metakovan," the anonymous chief financier of the NFT-centric fund Metapurse. For their $69 million, the winning bidder acquired the non-fungible token (NFT) linked to the artwork.

Beeple's art also earned the distinction of being the most expensive NFT ever sold, as well as the third-most-expensive artwork sold at auction by a living artist.

A portion of onlookers may be asking themselves what happened, and more importantly, what an NFT is in the first place.

What are non-fungible tokens

The work "token" in the phrase refers to a digital token, a cryptographic certificate for an object or item. Owning that token can infer ownership of something, be it one unit of a bitcoin or some other currency.

The "Non-Fungible" element refers to the token being completely unique and having properties that cannot be easily changed for another token that can be similar, but still different.

For example, a bitcoin is a fungible token as a person could sell one and buy another and it retains the same relative value of one bitcoin unit. More simply, if you change a $10 bill at a bank to two $5 bills, you still have $10 dollars on hand.

In the case of NFT, since the token is unique and there's generally only one available, it cannot be switched out with another of a comparable value.

This is the equivalent of having a magazine cover signed by Steve Jobs. Sure, you could trade with someone for another cover for the same magazine, but the one you would receive won't be the same as the one you traded away.

Since it's unique, there is no defined value to the NFT at all. While one bitcoin may be worth one unit of bitcoin or one dollar may always be worth one unit of dollars, the NFT can easily change in value and will always be priced based on other monetary systems, like dollars.

The ultimate value of an NFT can change over time, and in theory, become more valuable.

Blockchain keeps NFT unique and secure

People may be familiar with the term "blockchain," which is effectively a ledger of transactions.

For bitcoin and other digital currencies, the blockchain keeps track of token sales. This helps keep order in the digital currencies, as the log of transactions confirms the number of tokens in use, and potentially provides evidence of ownership to specific owners.

Due to the cryptographic nature of blockchains, any attempts to change one block will be spotted. This ultimately keeps blockchain secure.

In the case of NFT being associated with a blockchain, this can allow for parties to check the validity of the NFT. Typically this is built on top of one of the existing blockchains, such as Etherium.

The idea of an NFT can be applied in many different ways. For example, the sale of a ticket to an event could use an NFT for each ticket, which can help prevent it from being misused by others by keeping logs on the blockchain.

Digital artwork ownership: a problem is NFT trying to solve

While the sale of artwork has been a concept that has been around for centuries, it has pretty much existed only in the physical realm. Unlike a physical artwork sale where the original painting or sculpture can change hands, it is impossible to do the same thing with digital artwork.

Due to its very nature, it is relatively trivial to make an exact copy of digital artwork.

Though you can make prints based on a physical painting, the buyers of those prints know full well they aren't buying the original at all. This cannot be done with digital artwork using the original files, as those same files could easily be duplicated and sold again.

Since major art sales typically involve the original work, the last thing that a buyer wants is for the perceived value of their purchased artwork to be diminished. A second identical artwork lessens the value of the original as it's no longer unique.

NFT tries to work around that by effectively acting as a certificate of ownership for the artwork. While the digital artwork could be copied and distributed widely, there will only be one or a few valid NFTs that apply to the artwork.

Prints of the Mona Lisa may be hung up in frames around the world, but only one entity owns the real thing.

NFT "Ownership"

While the discussion of ownership is fairly straightforward for physical art pieces, the same cannot be said about NFTs. While the NFT infers the holder "owns" the artwork as presented, there's more to it than just that.

For a start, the NFT owner will be granted specific usage rights for the digital file from the artist, defining how it can be presented to the public, if at all. This can include limitations on venues where it can appear, or bans preventing it from being used in certain ways.

Artists may also elect to hold onto the ability to reproduce the artwork themselves despite selling the NFT, and can retain the ultimate copyright of the artwork too. It's even possible for the artist to earn a cut from a resale of an NFT beyond the original sale, depending on how the NFT is set up.

Furthermore, the ownership of an NFT may not necessarily translate to "ownership" of an entire work.

For example, YouTuber Logan Paul monetized a video stream where he unboxed Pokemon cards. Video clips of highlights were created, along with NFTs for each, and were sold off.

Each NFT would represent effective ownership of a specific video clip, but not the entire stream.

There's also the issue of uniqueness, as the artist doesn't have to create just one NFT. Instead, they could mint multiple unique tokens at the same time, with a limited number in circulation that won't be increased.

Using Logan Paul as an example again, he sold $504,990 in NFTs, which consisted of digital Pokemon cards using his likeness. The collection consisted of 945 "cards" with four levels of rarity.

Ultimately, buyers of NFTs through exchanges like Nifty Gateway or OpenSea receive an NFT they can store in a compatible cryptocurrency wallet, potentially an image or a copy of the digital file, and the knowledge that they "own" a creative asset.

Copyright and trust issues

Since NFTs can be generated based on practically anything digital, and that digital items can be easily copied, there's the potential for abuse. Specifically, there's nothing stopping anyone from creating their own NFT based on digital items generated by other people.

In one example reported by Decrypt on March 13, artist "Weird Undead" has found people stealing digital artworks from their tweets. The images were used to generate NFTs and were sold on an NFT marketplace, sales that the artist has tried to halt.

Weird Undead refers to the practice as "insane and pointless copyright infringement," one which only benefits the marketplaces and the people taking the images, not the artists themselves.

The practice isn't just limited to artworks. There have also been issues with people tokenizing tweets by others as NFTs and selling them. Again, the practice doesn't involve the person who wrote the original tweet, who would ultimately own the copyright for the text.

While it is entirely plausible for an artist or the creator of media to sue under existing trademark and copyright laws, the nature of how blockchain operates can make it difficult to find out who originally infringed to create the NFT.

There's also the problem of which marketplace to trust in the first place.

Multiple blockchain services could each claim they have records that a specific NFT is unique, and that they are the authority for the work. This is the equivalent of two auction houses claiming they are the venue of sale for a unique piece of art.

At this time, it seems that there is some cooperation between major marketplaces on the subject, though there is no guarantee things will stay that way in the future.

Add in that it is possible for people to set up their own marketplaces on blockchains, and it becomes harder to police the NFTs being put up for sale.

These are problems that will have to be addressed at some point, both to protect the livelihood of artists and to keep the sales of NFTs legal. For the moment, these problems haven't blunted the appetite for well-heeled buyers.

Why are NFTs popular?

The high-concept for using NFT is to provide a way for digital items to become sellable with ownership comparable to physical item sales. It accomplishes this by introducing a form of scarcity of ownership.

Just as there's only one original Mona Lisa that you can feasibly acquire, there are only one or a few NFTs for a digital artwork available to purchase.

As with other areas where there's only so much of a resource available, people potentially see value in an item and may acquire it.

This concept has surfaced countless times, with the rarity of items increasing their value over time, especially in areas where there are many things that could be collected. Examples include Beanie Babies, comic books, playing cards, and more famously, sneakers.

Naturally, this behavior can lead to enterprising individuals acquiring a commodity for future sale down the line. Much like art can be acquired as an investment, so can NFTs.

The difference here is that it effectively allows some ownership of a token connected to a work of digital art, an item that doesn't offer any guarantee of scarcity. This ownership, an effective certificate of ownership of digital art, is seemingly worth paying for by some people.

The value of an artwork is in the eye of the beholder, or realistically the eye of the market at large. If there is a perceived value, then that can translate into a transaction that gives the art actual value.

So far, it seems that NFT may be viable as an item for trade and retrade, and for profit, much like existing art.

An earlier NFT sale by Beeple for the artwork "Crossroad" fetched $66,666 originally. However, collector Pablo Rodriguez-Fraile sold it a few months later for $6.6 million.

Elsewhere, Twitter co-founder and CEO Jack Dorsey auctioned off his first tweet for $2.5 million. Companies are also capitalizing on the trend, with Taco Bell offering 25 NFT tokens, benefiting the Live Mas Scholarship.

Evidently, there is some value seen in NFT.

Given its flexibility and potential use on many different types of digital artworks and other content, it may be one that will stick around for quite some time. Its relative newness also makes it prime to grow, but only if its patrons continue to see future value in it.

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

-m.jpg)

Brian Patterson

Brian Patterson

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

16 Comments

Welcome to Bizzarro world, where information wants to be enslaved.

Time to fire up a random image generator and create some NFTs=Profit$

This reminds me of the Dutch Tulip bulb market bubble, and eventual crash in 1637. Something has value until it doesn’t...

In the US, artwork entering the country is duty free. I wonder if that also applies to digital art protected by NFTs, or whether someone importing NFT-protected art would have to pay duty when it entered the country.

Art has long been suspected of being a good way to launder dirty money. I would think NFTs would make it even easier.