Apple's transition away from Intel to Apple Silicon was a difficult gamble to undertake, with a profile of Johny Srouji revealing challenges including an internal debate over designing components, as well as the timing of the COVID-19 pandemic.

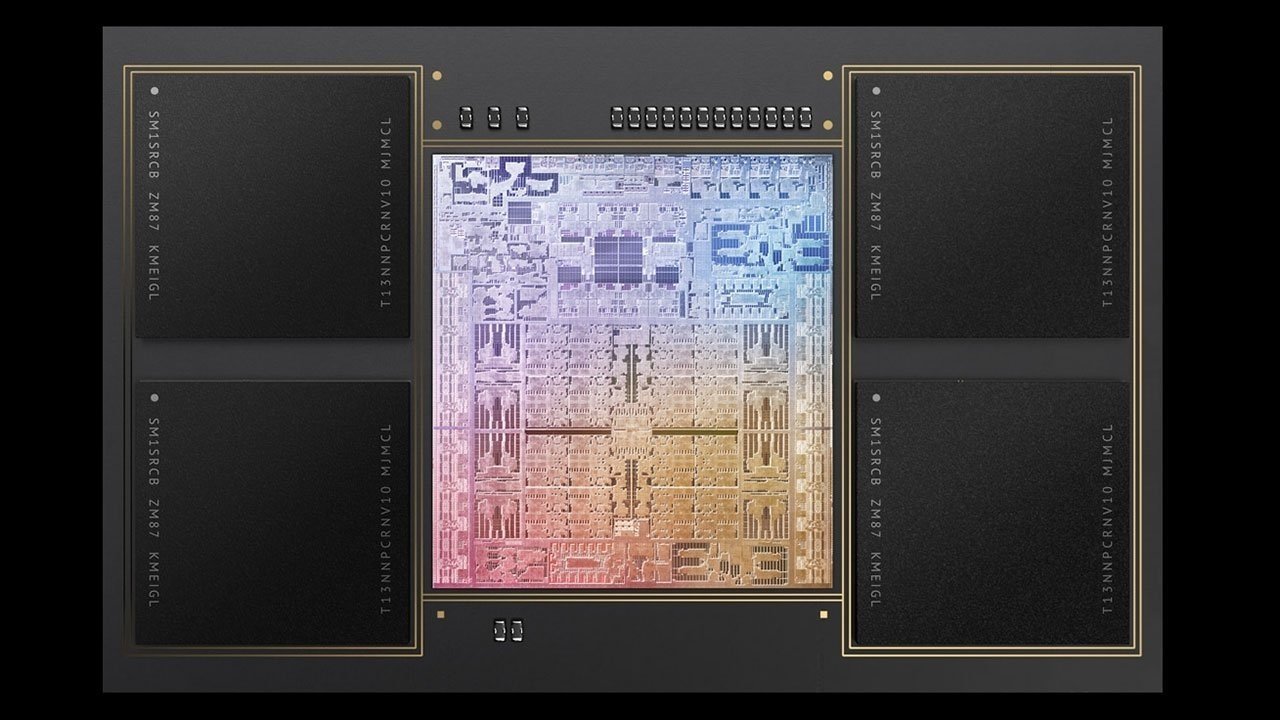

Apple's resurgence of the Mac and MacBook lineup is largely down to its creation and implementation of the M1 chip lineup, with its Apple Silicon components able to outpace its rivals. In a profile of Johny Srouji, Apple's SVP of Hardware Technologies, more light is shed on the design thinking behind the creation of Apple Silicon.

Apple had built a team up to include thousands of engineers working on the company's silicon for iPhone and iPad. Limited by the constraints of working from a battery, the team's designs also enabled deep integration with the hardware, to complete tasks that designers wanted its ranges to do.

However, a flashpoint occurred in 2017 when tech bloggers talked to executives, reports the Wall Street Journal, with Apple apologizing for shortcomings in its professional Macs. After continued complaints about low performance through using Intel chips, Apple stepped up its efforts to shift away from the chip maker.

The change prompted debate within Apple, Srouji confirmed, since computer producers don't tend to design such important components in-house. The move was considered risky, in part because the team had to design a chip architecture that would work from the cheapest Mac mini to the most expensive Mac Pro.

"First and foremost, if we do this, can we deliver better products?" said Srouji about the debate. "That's the No.1 question. It's not about the chip. Apple is not a chip company."

The team then had to work out whether it could deliver the chip, at the same time as increasing its numbers to deal with other projects and technological changes. "I don't do it once and call it a day, "Srouji adds. "It is year after year after year. That's a huge effort."

The process prompted Apple to expand its chip strategy to Macs, complete with a scalable architecture. A former engineer told the report Srouji's team had suddenly become a central point of product development, increasing Srouji's influence over time.

COVID-19 became a potential issue for Apple Silicon's development, with remote-work mandates impacting chip validation before production commenced. Rather than the usual process of having engineers view chips through microscopes in a facility, Srouji helped implement a process where cameras were used to perform the inspection remotely.

The rapid deployment was necessary to avoid any delay in production, but was quick due to the size and spread of Srouji's team. Spread around the world, the group was very familiar with working via video calls across time zones.

"What I learned in life: You think through all of the things you can control and then you have to be flexible and adaptive and strong enough to navigate when things don't go to plan," said Srouji in an interview. "COVID was one for example."

Apple is currently preparing to hold its WWDC event in June, one that could see the company introduce the next generation of its Apple Silicon strategy. Rumors have proposed Apple is working on introducing M2 chips in an updated MacBook Air and MacBook Pro later in 2022, which Apple may tease at the developer conference.

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

-m.jpg)

55 Comments

Out of all the desktop/laptop OEMs out there Apple was the only one with the balls to strike out on its own. As the article points, with tremendous risk and challenges. The rest remain locked down to whatever Intel or AMD does or does not have to offer. But since the debut of the M1 suddenly other OEMs are investigating producing their own SOCs.

One thing is certain for those of us who keep riding the Apple log flume, it’s a thrilling ride and you never know what’s around the corner, just like an Indiana Jones movie.

every time some shift like this happens, I go back and reread stories about NeXT and Jobs' wilderness years away from Apple. It's astonishing that he and the NeXT team followed the technology and seemingly lost every battle until he (and they) ultimately won the war. Learning to port NeXTSTEP OS to other chip architectures in the early 90s is still paying dividends today on a scale they couldn't have possibly imagined when they were just trying to survive. shocking success story, really.