In the decade and a half since the acquisition of NeXT, Apple was completely reinvented as a company, gaining new technology and direction from NeXT while being entirely rethought by a new management team led by Steve Jobs, including many executives and engineers from NeXT.

NeXT before Apple

Prior to Apple acquiring the company, NeXT Software had spent three tumultuous years trying to figure out how to sell its advanced operating system technology after abruptly jumping out of the hardware business in 1993 — after five years of failing to find a significant market for NeXT Computers in the late 80s and early 90s.

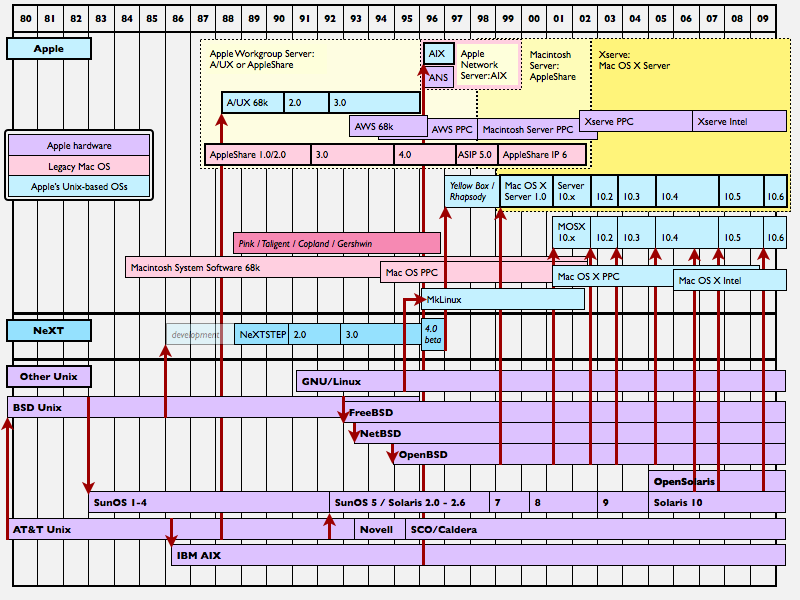

In its three year stint as a software company, NeXT announced plans to partner with Sun (and later HP) to create OpenStep, an open specification based on its NeXTSTEP operating and development environment, capable of running on top of other operating systems from Sun's own Solaris to Microsoft's Windows NT. Both partners ultimately backed out; Sun to focus on Java and HP to join Apple and IBM on Taligent, a project to essentially duplicate NeXT's technology.

NeXT had also developed WebObjects as a way to use NeXTSTEP's object oriented development tools to build dynamic web applications. Jobs began to view WebObjects as the company's primary asset, particularly in a market increasingly dominated by Microsoft, where there was no effective way to sell an alternative third party operating system.

Apple before NeXT

By 1996, Apple had ended up the only significant computing platform to survive the rise of Windows, kept afloat by sales of its Macintosh hardware as other alternative OS licensees, from IBMs' OS/2 to Sun Solaris to the BeOS to NeXTSTEP, floundered without a critical mass of buyers and developers in a PC market captive to Microsoft's exclusive licensing agreements.

While still in business, Apple was in rough shape, with its own efforts to modernize its classic Macintosh system software failing and time running out to maintain relevance in the computing industry. Apple had partnered with IBM (and later HP) to develop a NeXTSTEP-like system called Taligent, and had attempted to deliver its own Copland operating system, but neither effort materialized into a salable product.

Apple had started talks with Be Inc, hoping that the company's experimental operating system could breathe new life into its Macintosh line. While the BeOS could already run on Mac hardware, it was far from being ready to sell as a replacement to the existing Mac OS, and lacked core features such as a printing architecture.

After examining NeXT, Apple's then chief executive Gil Amelio, who had been brought in to turn the failing company around, realized that acquiring NeXT would not only give Apple a finished, proven desktop OS to replace the rapidly aging classic Mac OS, but also powerful the WebObjects, related development tools and a legitimate enterprise business.

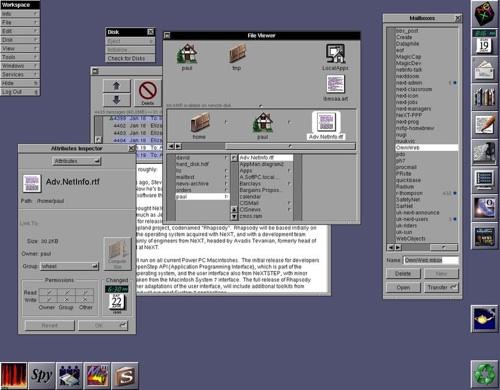

Mac users were less familiar with NeXT than Be, given BeOS's consumer/hobbyist focus and the fact that NeXT had been contractually prevented from entering the consumer market by Apple after Jobs left in 1985 to start NeXT with a variety of Apple engineering talent. Amelio was confident, however, that Apple could simply ship new Macs running NeXTSTEP within the next year, a strategy branded "Rhapsody."

Apple + NeXT

On December 20, 1996, Apple announced to the surprise of many that it would buy NeXT for $429 million in cash, along with 1.5 million shares going to Jobs, who would act as an ongoing consultant after the sale. NeXT's website described the acquisition as a "merger."

Virtually no one in the Microsoft-dominated personal computing industry saw Apple as a relevant player even after its acquisition of NeXT. While Apple quickly rolled out a public strategy for making its new NeXTStep operating system the new Mac OS and converting the OpenStep environment into a Yellow Box layer that could enable apps written for it to work seamlessly across Macs, Windows and enterprise Unix distributions, rather than being taken seriously Apple was shunned even by NeXT's existing customers.

Dell, a very visible client of WebObjects in its online store, abandoned its business relationship with NeXT and created a new online store with Microsoft. Sun and HP had also abandoned their OpenStep partnerships with NeXT, and few viewed Apple's backing of NeXT technology as commercially sustainable.

Apple began shifting its own goalposts as its Mac customers balked at adopting a more serious and complex Unix-based operating system. Even worse, Apple's principle Mac developers, including Adobe, Macromedia and Microsoft, indicated little interest in writing for Yellow Box, insisting instead that Apple merge the classic Mac OS and NeXT technologies to produce something modern that could still run their existing code with minimal changes.

What appeared to be a perfect merger between ideal partners began to look more like a mess. Apple was stuck in Mac OS licensing agreements with hardware makers that compelled the company to essentially give away its OS while also squandering its ability to sell its own hardware at a profit, as cloners were taking away its high end sales rather than expanding the Mac market as intended.

Apple was also straddled with retail distribution that simply sat its computers next to cheaper PCs without effectively demonstrating any differences between them. The company therefore had no obviously competitive products, no way to sell them, and no way to keep developers supporting its status quo or its intended future. Things looked pretty bleak for the Macintosh.

Apple's only other significant product was the Newton MessagePad, a tablet computer that was getting bypassed in the market by the much cheaper, simpler Palm Pilot while demanding a significant portion of Apple's attention and efforts.

On page 2 of 3: Jobs turns Apple Around, Apple goes open

The day after Apple purchased NeXT, Jobs wrote "Much of the industry has lived off the Macintosh for over ten years now, slowly copying the Mac's revolutionary user interface. Now the time has come for new innovation, and where better than Apple for this to spring from? Who else has consistently led this industry— first with the Apple II, then the Macintosh and LaserWriter? With this merger, the advanced software from NeXT will be married with Apple's very high-volume hardware platforms and marketing channels to create another breakthrough, leapfrogging existing platforms, and fueling Apple and the industry copy cats for the next ten years and beyond. I still have very deep feelings for Apple, and it gives me great joy to play a role in architecting Apple's future."

After first expressing a lack of interest in taking over management of Apple, Jobs announced the following July at the 1997 summer Macworld Expo that he would be acting as the company's interim chief executive until a replacement to Amelio could be found.

Jobs had led the effort to remove Amelio (both shown below, at Macworld Expo 1997), and immediately began undoing his decisions. That included Amelio's spinoff of Newton, which Jobs brought back into Apple just weeks after the new subsidiary had been created. Jobs then orchestrated a series of cuts that simplified Apple's product lineup and scope.

Key among Jobs cuts included the abandonment of the Advanced Technology Group, a research lab that had generated lots of products that weren't making any money, including QuickTime TV, QuickDraw 3D, OpenDoc, HotSauce, Macintalk speech synthesis and Newton handwriting recognition. Jobs also terminated the company's cloner contracts, enabling Apple to maintain control over the destiny of the Macintosh.

While cutting a variety of pet projects and bringing in Tim Cook from Compaq to similarly straighten out Apple's convoluted global operations, Jobs also built Apple a new online store using WebObjects, similar to the one Dell had abandoned. This enabled Apple to begin selling "built to order" Macs direct to users.

Jobs also slashed the number of Macintosh products down to just a tower and notebook G3, subsequently adding the iMac as an iconic new compact all-in-one the next year, followed by the consumer iBook notebook in 1999. While cranking out new hardware, Jobs also reinvigorated the classic Mac OS, adding what could be salvaged from the Copland project while working on Mac OS X (based on NeXTSTEP) as its eventual replacement.

Jobs' Apple also focused on how to grow Mac sales, launching an effort to begin building Apple-owned retail stores while also buying up key software developers to assemble a suite of Pro Apps and consumer counterparts in iLife, followed by an iWork suite of productivity apps.

Apple goes open

In addition to its continued work in developing proprietary software, Apple's NeXT-centric development team announced plans to make the core Unix OS foundation of Mac OS X an open source project named Darwin. Along with Apple's own open code, the company began funding open development of existing and emerging projects, ranging from an adoption of open specifications such as OpenGL (in place of Apple's proprietary QuickDraw 3D) to the purchase of and continued maintenance of CUPS, the open printing architecture used by Mac OS X and other free Unix and Linux distributions.

Apple also embarked upon building its own Safari web browser, developed under an open source WebKit program that would eventually shift the balance of power on the web from Microsoft's Internet Explorer to open source. Following the same development strategy underlying the open development of NeXTSTEP's BSD Unix core, WebKit has become the world's most popular web browser engine and the only significant browser among mobile devices.

Apple also began plans to completely replace the GNU Compiler Collection development toolchain of GNU/Linux (shared with Mac OS X) with an advanced new LLVM compiler architecture under development at the University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign, and offered under under a BSD style open source license. Apple added LLDB and Clang to the mix, dramatically shifting how the future of Unix-like software would be written.

In addition to backing OpenGL, Apple also created the OpenCL specification for using GPU hardware to run general purpose number crunching, acting as neutral intermediary to gain the support of competing graphics vendors. Apple also played a key role in advancing WebDAV, CalDAV and CardDAV as open standards for working with Internet files, calendars and contacts.

Additionally, Apple cracked open the highly proprietary worlds of audio streaming, video encoding and distribution by supporting MP3, AAC, and MPEG H.264, defeating plans by Sony and Microsoft to replace open audio playback with proprietary standards intended to lock down music. Similar efforts to control video playback streaming on the Internet by Adobe's Flash were dashed when Apple leveraged all of its market power to break the back of Flash, opening video to everyone.

On page 3 of 3: Jobs' golden decade of Apple, A world without Apple's NeXT, What's next for Apple

By 2001, five years after buying NeXT, Apple was ready to open its first retail stores, ship its first build of Mac OS X, and launch what would become its highly disruptive move into consumer electronics with the iPod. The iPod itself would become so important to Apple's business that it served to remove the "computer" from name of Apple Computer.

Jobs outlined a digital hub strategy that made the iMac the center of a variety of devices, a strategy that lasted throughout the 2000s as Apple continuously improved upon the core foundation of Mac OS X and progressively enhanced its hardware.

In the middle of the 2000s, Jobs directed Apple to switch from PowerPC chips to Intel, a move that enabled Mac users to run Windows, therefore making its machines more accessible to corporate users and others that still needed to work in the Windows world.

Around the same time, Apple also began work on developing a tablet computer, efforts that materialized in the iPhone in 2007. The iPhone and its scaled down version of Mac OS X, eventually named iOS, would become a much larger business than the Macintosh itself.

By the end of the decade, Jobs launched the iPad as a full priced tablet computer, with its road to revenues paved by the wildly successful iPhone. While the iPhone had entered a fiercely competitive, deeply entrenched market and embarrassed all incumbents while rocketing upward to become the top selling phone globally, the iPad, like the iPod before it, largely created its own market, one that competitors have yet to encroach upon.

Between 2001 and 2010, the market value of Apple's shares grew from a split adjusted $10 to $315, leaving the company the most valuable technology company on the planet, earning the most revenues and the most profit. Apple had broken out of its limited niche in computing, took over and transformed the market for music and movies with the iPod and iTunes, mastered the mobile phone industry (where its only remaining credible competitor is an open source project offering itself for free) and introduced a new mobile form factor in computing with the first successful tablet.

A world without Apple's NeXT

Without NeXT, and without the drive and creativity and vision of Jobs, the man behind the company Apple purchased 15 years ago, Apple Computer would likely have instead simply been bought out and dismantled before the 90s had even ended. The Macintosh would have become a footnote in history much like the Amiga.

The personal audio player market would likely have been dominated by Microsoft and its PlaysForSure system, which locked down songs and limited which ones users could burn to mix CDs at the whim of publishers.

Without Mac OS X, Microsoft would still be working on versions of Windows 2000 (not XP, which was named to coincide with Apple's product). There would be no Windows Vista/7 and its advanced GPU driven compositing graphics engine that was derived directly from Apple's pioneering efforts with Mac OS X's Quartz Compositing.

Without the iPhone, there would be no easy to use touchscreen mobile devices. Instead, Android would look just as it did before the iPhone: a button-centric alternative to PalmOS and Windows Mobile and the Blackberry, none of which would have changed much in the past four years. There would be no tablets. There would be no effort to build Ultrabooks just like the MacBook Air. We'd only have a wide variety of cheap, low quality netbooks to choose from.

The profits of Nokia, Microsoft, Nintendo, Sony, Palm, HP, Adobe and others would be largely unchallenged, preventing them from extending much effort to improve their offerings. Microsoft wouldn't be building a low cost App Store for its mobile and desktop platforms, and Google would still be focused on selling low end notebooks that can only browse the web. The companies that today are failing and don't know why or how to stop failing would still be running the tech industry.

What's next for Apple

While the world this year lost the man who founded both Apple and NeXT, and who managed to fix Apple after it strayed away from his vision, and who assembled a team capable of restoring the notion of greatness being at the intersection of technology and liberal arts, Jobs has left behind a clear legacy that begs to be followed, not just by his executive team at Apple, but by other companies around the world.

Apple is stronger than ever as a company. It has global retail operations in place, a strong position in mobile and desktop products, sits on the bleeding edge of research and development and is flush with cash, all things it desperately lacked 15 years ago.

But Apple also now has the ability to recognize when its failing and take action. Over the past 15 years, Apple has grown capable of backing out of efforts that were losing money, even if the strategy appeared to be right. Apple pushed into the server market with the Xserve, Xserve RAID and Xsan, only to find that simply offering a much cheaper alternative wasn't going to suffice in a market that demanded handholding customer service and support.

Apple has learned that quitting when you're in the wrong place is as important to success as pushing ahead when you're on the right track. Apple has similarly scaled back its Pro Apps to deliver powerful functionality for the mainstream, rather than trying to cater to tiny minorities of pro users that can be better served by specialist developers. And its executives regularly repeat the idea that Apple knows what not to do.

Just fifteen years ago, Apple couldn't say no, couldn't say yes, couldn't deliver upon its plans, and couldn't convince investors that it was worth believing in. It's been a remarkable decade and a half for the company that rediscovered its founder and reshaped the industry to fit his vision.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

68 Comments

Interesting read...

I recalled being in Hong Kong at the time reading the story from a Mac Performa at a retail store.

I agree, very interesting read. When programming objects I still see NS nomenclature that originated with NextStep. The NextStep prefix (NS) is used extensively on MacOS and even iOS programming.

Such as NSStrings, NSDictionary, or NSUrl. The list is very long!

Yes, very interesting, indeed. Where does DED get all of his history info from? A compilation from Wikipedia and other various sources?

Can't wait for the trollers to pick apart some of the statements in this article!

Very nicely written, DED.

I learned a lot and I appreciated the effort to add context. I hope that the facts are all accurate. But seriously, I think that the Feature format works VERY well. It allows a lot of latitude, and gives a lot of opportunities for original insights.Features seem to suit your style much more so than straight news articles. News doesn't allow for as much Why as feature writing does.