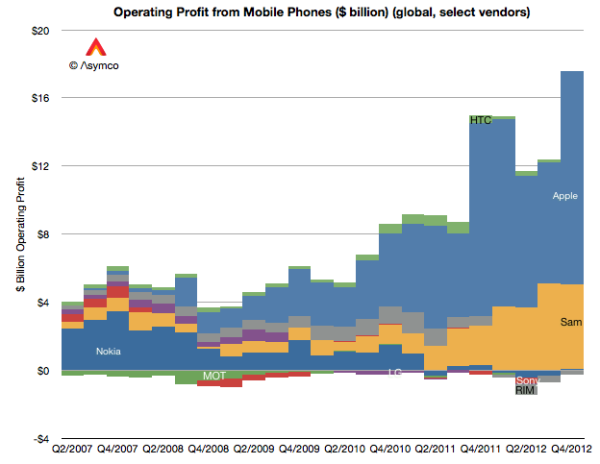

Over the last six months, Apple earned $22 billion on revenues of over $98 billion, while selling 85 million iPhones and 42 million iPads globally. The profits Apple is now earning in mobile dwarf the best mobile profit performance records set by Nokia in 2008 by more than a factor of three. Why are Apple's competitors not beating back its advances?

Source: Asymco

How is it possible that Apple has managed to rapidly sop up the majority of the entire mobile device industry's profits, and has since then continued to dominate the direction of the industry? The answer is an interplay of three factors: a product with clear value to a large audience; a platform that makes it sticky and resistant to competitive erosion; and its ability to fuel auxiliary sales among supporting partners.

Advent of the second coming of Windows

Ever since Apple introduced the iPhone, conventional wisdom has insisted that Apple "shouldn't" have been able to break into the smartphone industry to start with, let alone been able to outmaneuver the well funded efforts by a variety of established vendors for this many years, with no real end to its reign in sight.

Pundits have been watching for history to repeat with the emergence of a new "Windows of smartphones," first identifying Palm OS as a potential new Windows of smartphones, then Linux, then Windows Mobile, then Symbian Foundation, then Android, then Windows Phone (with some variation in sequence). Samsung has placed bets on each of these smartphone platforms.

While many members of the tech media have begun to agree among themselves that Samsung has now rivaled or perhaps bested Apple (at least in smartphone unit sales), the reality is, as Horace Dediu of Asymco recently noted in a tweet (accompanying the graphic above): "Samsung gained a level of profits equal to the industry 5 years ago. Apple created 2x value on top."

Apple isn't competing within a market that existed in 2007. It has built a much larger one around that "proto-smartphone" market, while Samsung has effectively taken over the old market for smartphones once dominated by Nokia.

If you're looking for a "history repeats itself" event, you could observe that Apple is playing the part of Microsoft this time around, while Samsung is playing the old Apple: one of the original PC makers who survived the onslaught of this new Windows and has wiped out the old competitors of the early era (the Ataris, Commodores and Acorns) to carve out a small niche, albeit one that's a lot less profitable than the business of the new larger, leader.

iOS is the new Windows

Essentially, Apple's iOS has become the Windows of our modern era. Pundits have desperately tried to instead link the iPhone to the fate of the original Macintosh, allowing them to then imagine who will be the modern day Microsoft to relegate Apple into a minority share, niche player. As a broadly licensed (and free!) platform, Android has been often suggested for this role in recent years.

The problem is that the principles (primarily the three listed above) that helped make Microsoft's Windows PC successful in the 1990s are now at work for Apple, not for the alternative platforms seeking to inherit the commercial success and longevity that the Windows PC enjoyed. In particular, these principles are not working to support Android.

While Android gets lots of ink for its success in spreading itself, it simply isn't generating the Windows-like profits that established Intel-based PCs running Microsoft's software as the dominant desktop computing platform for over a decade. Android has clearly become an important software project, much the same way that WebKit has. But Apple isn't amassing its billions for playing a key role in distributing free software for the world's web browsers.

Somewhat ironically, just as Samsung is now playing the role of the Old Apple of the mid 90s (the niche, sole survivor of the Windows 95 onslaught), Google's Android is playing the role of the Classic Mac OS: beloved by its supporters, distributed basically for free, and supporting a healthy business without any real hope of ever dominating profits comparable to the rival megaplatform that has grown up around it.

A product with clear value to a large audience

The first aspect of how Apple attained and maintains its current position explains how the company got its foot in the door. The iPhone, when it was first unveiled in 2007, so captured the attention of consumers that it figuratively sucked all the oxygen out of the mobile industry, immediately becoming a famous household brand worldwide.

It was a product with clear value to a large audience, a concept cleverly captured in a photo posted to Reddit comparing 1993 to 2013.

The iPhone's immediate, global superstar status as a new computing product had much less in common with Apple's own introduction of the 1984 Macintosh than it had with the megalaunch of Microsoft's Windows 95. The original Macintosh got some attention, but sales didn't immediately take off. It was relatively expensive, at a price that, adjusted for inflation, would today feel like a $5,655 price tag. It was clearly a product for eager, early adopters.

Ten years after the Mac's release, Microsoft could leverage all of the goodwill, desirability and value Apple had built around its Macintosh concept to sell a software package that, for existing DOS PC users (who were entrenched and widespread years before the Mac first appeared), what seemed like an extremely cheap way to have nearly a Mac without paying much for the privilege. Windows 95 was a product with clear value to a large audience.

Android does not replicate the high value/low cost proposition of Windows 95 because you could never just buy a retail box of Android and install it on your existing BlackBerry, Palm Treo, WiMo or Symbian device and get an experience that feels like the iPhone. You couldn't even hack it to work. In fact, throughout the history of Android, not only has it been difficult to get updates for existing Android devices, most users don't even seem aware that they need updates.

I've interviewed all sorts of fervent Android fans and casual users, few of whom even knew what version of Android they were using. None seemed concerned at all about it. The only common thread among adherents was that they wanted something that wasn't Apple. More casual Android users picked up a device because it was cheap, but these users, who make up the majority of the Android installed base, have nothing holding them to the platform.

Most Windows users weren't trying to avoid Apple; they were trying to get an Apple-like product without paying a lot for it. They then got locked into the sticky Windows ecosystem. Android's fans therefore have a lot more in common with original Mac or Amiga or OS/2 fans than the masses of Windows users of the 90s. They want something unique and interesting, not a simple product with clear value to a large audience. Non-fan Android users have very little loyal attachment to the platform.

Leverage and transform for disruption

Effecting disruption of an industry by introducing a new product with clear value to a large audience isn't easy. You have to capture the attention of an audience, while ramping up production to compete against the status quo. It certainly helps if you are the status quo to start with, and particularly if you're not operating under the shadow of someone else's existing success.

Microsoft's ability to transform itself from an MS-DOS licensee into a company offering a graphical desktop computing experience that was "like the Mac but better in some ways" (as Windows 95 was frequently described at the time) has far more in common with Apple's iOS over the last decade than the appearance of Android.

Like Microsoft, Apple had an existing, successful product it could leverage and transform. In fact, Apple had two: the Mac and the iPod. Google started out with the Android Linux/Java platform it acquired with Andy Rubin. The difference is that MS-DOS, Macs and iPods were all very profitable businesses with loyal users; Rubin's Android originated as a niche player with Danger, and Sun's mobile Java platform it was based upon, while widespread, had never generated much in the way of real profits and had established no loyalty among its customers.

MS-DOS was destined to fade away in the early 90s to be replaced with a graphical desktop. In the years before Windows 95 appeared, the overall industry had once bet upon Microsoft and IBM's joint OS/2 product or something new like IBM and Apple's joint Taligent project as replacing DOS. Instead, Microsoft leveraged and transformed its own position as the vendor of MS-DOS to introduce Windows, which became so successful that there wasn't any room left at the table for OS/2 or Taligent.

Similarly, lots of people were observing around 2005 that the wildly successful iPod would run into competitive erosion from smartphones capable of playing MP3s. Instead, Apple leveraged and transformed its booming iPod business to launch the iPhone, and subsequently the iPad, which continue to syphon off most of the profits available in the in mobile market.

It was less apparent several years ago that Macs and PCs would increasingly be replaced with mobile devices. Back in 2000 a Japanese exchange student I lived with described how essentially nobody in Japan (particularly younger people) used desktop PCs anymore, instead preferring the mobility of sophisticated phones. I had a hard time believing that could be true, but sure enough, ten years later it was clear that lots of people all around the world were more interested in spending their time poking at smartphones than sitting at a desktop with a mouse or carrying around a notebook.

Having built the Mac back into a very popular computing platform, Apple had a second product with a significant audience it could leverage and transform to deliver the iPhone and later the iPad. Apple essentially combined its two products to create the iPhone: leveraging the compact mobility of the iPod as an integrated media-savvy device and the software development and OS platform of the Mac. There was no technical equivalency to Microsoft's 1995 Windows 95 replacement of plain old MS-DOS, but there was an close analogy. The pitch: "here's a new product that's better, it's affordable, and it packs readily apparent value."

While you really had to want a smartphone as an early adopter in order to have bought one prior to the iPhone, the iPhone was immediately seen as desirable to a broad spectrum of users who'd never been tempted by Microsoft's windowing WinCE experience or other smartphone platforms of the day.

Key to stoking that demand was Apple's strong product: it served clearly valuable purposes, notably being an iPod (which many users were already very familiar and comfortable with), being a very decent web browser (which users also readily recognized as a great thing) and being a cell phone (something that packed not just clear utility, but also brought with it a clear business case for a sale: you need a phone anyway, might as well get this super smart one rather than a complex, difficult to use one that wasn't great at serving as an iPod or browsing the web).

Had Apple just stopped there, the iPhone would quickly have been buried in a flurry of copycats or alternatives that learned how to also offer decent web browsing and play videos and songs. After all, Apple had also introduced laser printing with the LaserWriter in the mid 80s, brought tablets into the mainstream in 1994 with the Newton MessagePad, and launched the pioneering QuickTake digital camera in the mid 90s. It eventually lost dominance of all three new product categories to competitors.

What has changed that enabled the company to turn its more recent new product introductions of the iPod, iPhone and iPad into long term businesses, maintaining its dominant position across mobile devices?

A platform that makes it sticky and resistant to competitive erosion

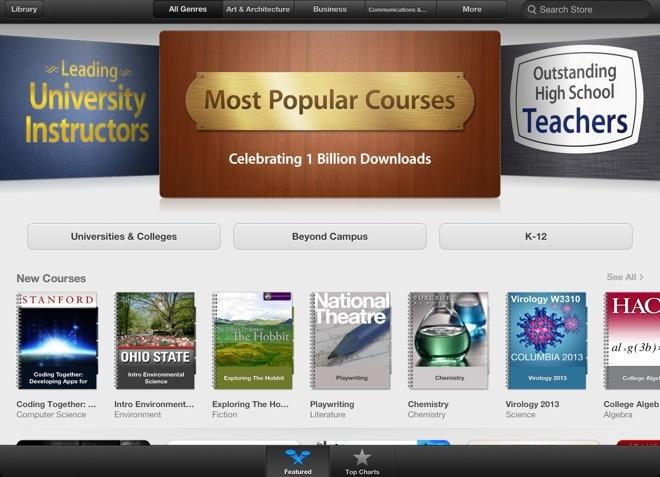

The second factor that helped iOS was the ecosystem Apple had already built around iTunes. This included a library and store of content in iTunes, the easy synchronization of content originally created for iPod, and specific efforts to drop anchors in important industries: things like iTunes U for education, support for Enterprise users, and a compelling app ecosystem that carefully curated (sometimes too carefully) the market for iOS software to ensure that developers could make money creating new value for iOS users and that corporations could customize private apps for their own internal uses.

This is much more difficult to achieve than Apple made it look for iOS, or as Microsoft made it look for Windows back in the 1990s. In fact, Apple had previously suffered through agonizing efforts to maintain the Mac platform and keep developers from all leaving for Windows in the 1990s. It knew all too well how important developers were to the platform. It's not just hard to build a new platform, it's exceptionally difficult to build one in the shadow of a very successful, larger platform.

Google, Samsung, Amazon and Microsoft are all working to build similar mobile ecosystems for their Android, Kindle, TouchWiz/Bada/Tizen and Windows Phone platforms, but they all have little to leverage and transform apart from minority segments of customers attracted to low priced hardware. These customers are not very valuable because they don't attract the kind of developer effort that reinforces the value of the underlying platform and ecosystem, creating a vicious cycle of failure. Complicating this is the fact that there's already one that's well established: iOS.

Once reason why the Old Apple could survive through the Windows era of the 1990s was because Apple had already created a niche status among customers ready to pay for premium hardware. While many PC users scoffed at anyone who'd pay more for a Mac, the reality was that those premium consumers kept the platform alive. Once Apple began trying to chase pure market share with low end models like the mid 90s Performa line, it began collecting an audience of low value customers that did little to shore up the value of its platform.

Similar efforts by Google, its Android licensees, Microsoft and Nokia to flood the market with low end, low profit devices enable those platforms to register an uptick in unit market share, but don't have a valuable impact on supporting ecosystem because those low end users are much less likely to pay for apps and content that supports the development of new apps and content.

Microsoft has even failed to leverage and transform its very strong position in desktop Windows PCs to create a platform that makes it sticky and resistant to competitive erosion. Metro was a effort to do this, but it has clearly failed. Google's lax management of Android's software platform has resulted in an app platform that isn't sticky enough to keep Android customers from upgrading to iOS.

Similarly, Google's lax management of Android's software platform has resulted in an app platform that isn't sticky enough to keep Android customers from upgrading to iOS. Even many satisfied Android smartphone buyers also buy an iPod touch or iPad to have access to Apple's iOS platform, rather than seeking out a Galaxy Player or Nexus tablet.

That's the kind of erosion that Apple's beleaguered 90s era Mac platform suffered at the hands of Windows PCs. Today, Apple's working hard to make sure that it's easier and more attractive to buy an iOS device than to shop around for alternatives on various platforms.

There's nothing too controversial or really novel about noting that Apple is doing a good business with iOS because it started with a good product and then built a rich, sticky ecosystem around it. But there's also a third component that is also helping Apple to maintain a lock on profits in the mobile industry.

The ability to fuel the auxiliary sales among supporting partners

When Microsoft copied the Mac's desktop environment to launch Windows 95, it leveraged its background as the vendor of MS-DOS to establish strong marketing partnerships with Intel and various PC hardware makers. Windows software was a killer app for hardware vendors who were trying to sell computers against Apple's Macintosh.

Microsoft was extracting the most profits from the PC industry, but it was also enabling Intel to sell chips and hardware makers to sell PCs. Both Intel and PC makers would also have made money selling Unix PCs or DOS PCs, but if they supported Microsoft Windows, they could earn even more money because they were tapping into a platform customers were asking for by name. That demand was enough to push Intel and PC makers to support Microsoft even when it wasn't in their long term interest, effectively making them Microsoft's indentured servants.

Eventually, PC makers couldn't afford to not sell Windows, forcing them to endorse Windows to their detriment and blocking them from supporting alternatives ranging from OS/2 to Linux to ChromeOS because consumers demand Windows. At the same time however, there hasn't been much criticism from Intel or PC makers (at least until recently) about the constraints and costs of Windows because it has fueled their sales. Now that Windows 8 isn't continuing to do that, they're starting to complain. Apple has stoked a demand cycle for iPhone that also fuels a critical demand for data service.

Somewhat similarly, Apple has stoked a demand cycle for iPhone that also fuels a critical demand for data service. Rather than partnering with hardware makers as Microsoft did, Apple has partnered with mobile service providers. So many customers were flocking to buy the iPhone by name that Apple could extort favors from the carriers it chose to do business with. AT&T willingly gave Apple control over apps and content sales, software updates and key services like Visual Voicemail because access to the iPhone had the ability to fuel the auxiliary sale of a killer app: expensive data service.

While Microsoft had the market leverage in 1995 to push essentially all PC makers to support Windows in one fell swoop, Apple had to slowly built out partnerships with select carriers worldwide. It didn't have an agreement with Verizon, the second largest carrier in the U.S., until its fourth year on the market. It gained the number three carrier (Sprint) and the support of several US prepaid carriers nearly a year later, and has only achieved support across the top five American carriers when it partnered with Tmobile and US Cellular in its sixth year on the market.

Imagine if Microsoft had only started selling Windows 95 with HP PCs, and wasn't able to sell Windows through Dell until 1999, and couldn't reach agreements with the majority of PC makers until 2001. Apple is just now reaching the point where most of the primary service providers carry the iPhone. It may be hard to believe, but Samsung, Nokia and BlackBerry still have established sales agreements with far more mobile carriers globally.

While Microsoft demanded co-marketing and exclusivity agreements from its PC partners, Apple has asked for more from the carriers: control over customers, handset designs and software and service features, and massive sales commitments, paid for up front. These demands were a tall order, explaining why it took so long for Apple to sign up the majority of US carriers as iPhone sellers.

Apple could only do this because it had the first two factors: a product with clear value to a large audience and a platform that makes it sticky and resistant to competitive erosion. Armed with a proven ability to sell customers lucrative data contracts, Apple can demand a lot from carriers.

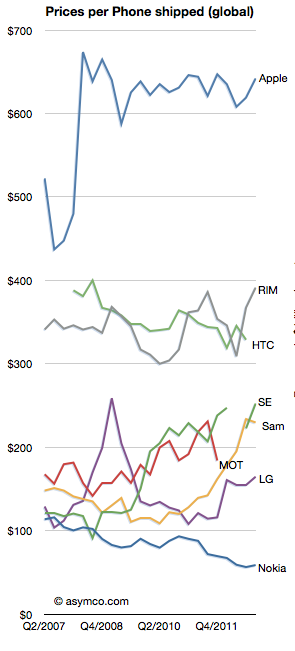

Highlighting Apple's leverage power is the fact that many carriers were adamantly opposed to partnering with Apple until they realized they had no other option. The iPhone is expensive for carriers (as noted by Dediu's average selling price chart for phones, above) in the same way that Windows was more expensive than DOS or Linux. But also like Windows, Apple's iOS attracts enough buyers to more than make up for the amount Apple asks from its partners.

After the failed launch of BlackBerry's iPhone-like Storm at the end of 2008, Verizon bet heavily on Android as a second attempt to duplicate the iPhone's ability to attract buyers and sell data contracts. Verizon mocked the iPhone in 2009 in an "iDon't ad" campaign and continued to assail iPhone 4 through the middle of 2010 in ads that promoted Motorola Droid X.

However, Android as a platform couldn't match the iPhone in attracting valuable customers to Verizon's network. As a result, Verizon embraced the iPad at the end of 2010 and added a CDMA version of iPhone 4 at the beginning of 2011. As a result, the company announced its largest launch ever.

Sprint and T-Mobile have similarly noted to investors that their inability to carry the iPhone were their top reasons for losing customers to rival carriers. After Sprint joined Apple as a carrier, it too announced its most successful smartphone launch ever.

At the end of 2011, Mary Dillon, chief executive the fifth largest American carrier U.S. Cellular told analysts her company had opted against carrying Apple's iPhone because of its upfront expense, describing the investment as "unacceptable from a risk and profitability standpoint."

A month later, Ted Carlson, the chief executive of U.S. Cellular's parent company TDS, revealed at the UBS Global Media and Communications Conference that the carrier was focused on building out its 4G LTE service first, before trying to offer the iPhone.

"We're never going to say never about the iPhone," he said. "The iPhone for us would need to be at the cutting edge of where we're going, and then there might be an opportunity to consider it."

Dillon has since followed Verizon, Sprint and Tmobile in changing her tune, recently stating, "we have a number of strategies in progress to increase loyalty and attract more customers, including our announcement today that we will begin offering Apple products later this year."

As noted in a tweet by Dediu, "U.S. Cellular promised to buy $1.2 billion worth of iPhones over three years, That's roughly 2 million phones."

In reporting the about-face, a report by AP noted, "In the 18 months since she talked about rejecting the iPhone, the company has lost 268,000, or 5 percent, of its customers on contract-based plans, which are the most lucrative."

Fated to go the way of Windows?

Apple, like Microsoft, has a huge platform advantage that it could lose if if fails to keep the iPhone a product with clear value to a large audience, and iOS a platform that makes it sticky and resistant to competitive erosion. It's also at risk if it loses the ability to fuel the auxiliary sales among supporting partners. There's no indication that Apple is yet slipping in any regard, but its clear that its competitors are aware of these factors, and are working hard to chip away at public perception.

Microsoft is actively losing its Windows platform dominance as the iPad erases the Windows PC's status as a product with clear value to a large audience. Windows itself is also losing its position as a platform that makes it sticky and resistant to competitive erosion. And increasingly, Windows is losing the ability to fuel the auxiliary sales among supporting partners. Apple now has a roadmap of "don'ts" to follow if it wants to avoid Microsoft's fate.

These include ignoring problems like Windows XP's security flaws until they became massive distractions; failing to update the platform for years and then introducing massive changes like Windows Vista; and spending billions copying competitors efforts (Zune, Slate PC, Surface) rather than identifying new, original businesses. So far, Apple has avoided these particular traps while Google's Android has fallen for each of them.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

225 Comments

Interesting article.

It goes to show the market is dynamic, and it's a matter of innovation. 10 years ago who would believe that M$ no longer is the dominant company, let alone being beat by a company that was ready to bankrupt at any moment?

Also, "Source: Reddit User Submission"?? Could you not attribute it to the actual reddit user?

http://www.reddit.com/r/pics/comments/1cbken/1993_vs_2013/

Some valid points.

Nice editorial, worth reading, but I do not agree with it.

Apple is losing market share worldwide and sales (numbers) are not growing at the pace of others. Yes, you may say that's because others make cheaper devices and some OEMs are on crisis and the market (worldwide) is far from saturated, but the fact is that even Apple's profits are down, so...

The conclusion is that they reached the maximum of the current business model, and that's a great business model. However, for iOS to be dominant, the leader, they need something else.

For me, it seems obvious that another premium high end line, with a bigger screen and software to take advantage of it, and even a cheaper line (250€) that offers something that the others don't (put an a5 chip, 2 year old components but just give it the same camera as the iphone 5, so it gives something that the competition can't offer at that price) are a fast, secure and solid way to create a platform that will dominate for years to come.

I want that, because for the first time the ones dominating are the ones that truly innovate.

Silly comparison.

"Apple is losing market share worldwide and sales (numbers) are not growing at the pace of others. " it's usual business for Apple. - anyway, the new Windows is Android. Same business, Same road, Same boring stuff.