Apple's Siri, Spotlight extend Google-like search inside iOS 9 apps, without tracking users

The biggest announcement at WWDC— with the most relevance to developers and end users— appears to be new Apple's Siri and Spotlight search services that deliver results including deep links within apps. Here's why.

Why in-app search is a big deal

When Apple introduced the iOS App Store in 2008, it was a bit like the early days of the Internet: you could only browse through catalogs of titles, guided by simple descriptions or perhaps word of mouth recommendations. Older readers may recall having browsed through a similarly simply index of Internet content available from services like Archie, Gopher and FTP.

In short order, Apple added curated lists of popular titles and hierarchical groupings by subject, bringing the App Store experience into line with the early web era of Yahoo listings, where you could search for websites, but only expect to get simple results based on metadata labels or name matches.

The new in-app search of App Store titles in iOS 9 achieves something new: a Google-like index where deeply buried content is surfaced by a Page Rank-style meritocracy of relevance and popularity— except that it's not being delivered by Google, but by Apple.

How iOS in-app search works

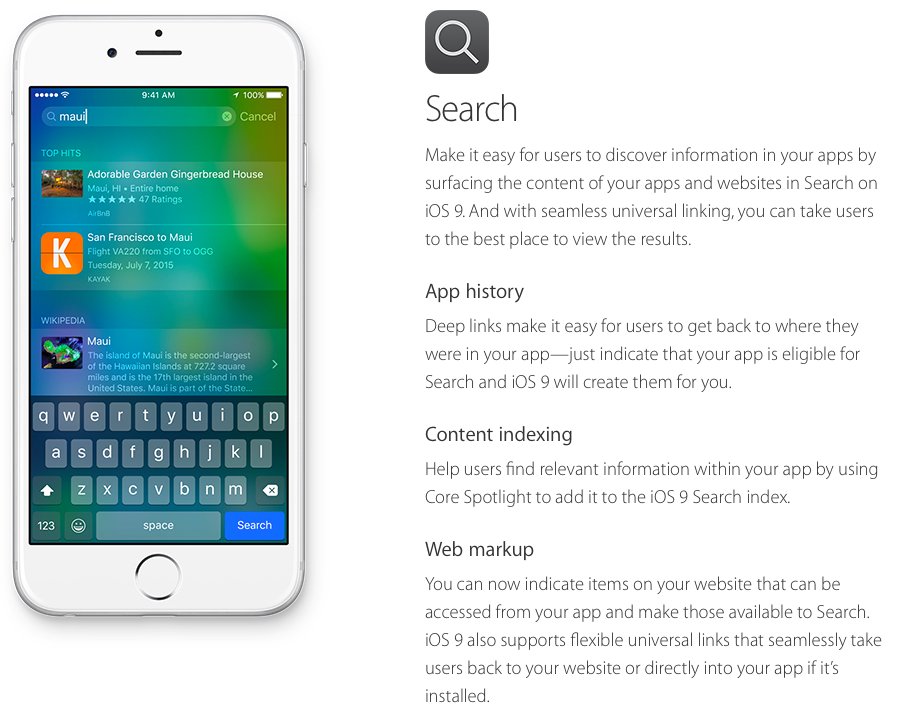

The way in-app search works in iOS 9 is based on a combination of two mechanisms. One is CoreSpotlight, which offers a way for developers to index content within their app (such as specific listings within Airbnb, an example Apple demonstrated at WWDC).

After a developer indexes their in-app content as public, once enough users perform local searches matching the indexed content (such as a specific Airbnb listing), those local search matches establish that a given result is popular enough for Apple to recommend publicly to users searching via Spotlight, or to automatically offer as Spotlight Suggestions, even for users who haven't installed the Airbnb app.

This percolates useful information that other users find relevant to the top of search results, similar in concept to how Google's Page Rank identified useful information in web pages by the number of incoming links pointing to it. By sharing popular search results publicly, this also provides a new level of exposure— in front of hundreds of millions of users— for valuable content within developers' apps, an idea greeted with lots of applause by WWDC attendees.

In addition to public content indexed by the app developer, Apple will also incorporate deep content from apps defined by NSUserActivity. That's the same mechanism Apple introduced last year as the foundation of Continuity's Handoff feature. For Handoff, it identifies an activity in progress on one device that can be replicated on another, such as migrating a web page the user has on their iPad to their desktop Mac.

For in-app search, the same "App History" process encapsulates a user activity that one person has performed, which other users may also find useful. For example, if you accessed a great recipe in an app, NSUserActivity could later help return you to find the recipe again in a Spotlight or Siri search. And once enough different users have performed the same search, arriving at that same recipe, Apple's global index would recognize that app's recipe as a valuable result for others searching for something similar.

In addition to a recipe, other relevant results might include a concert ticket in Eventbright, or treatment for a sprained ankle in WebMD. In-app search means that rather than searching for an entire app, users can search for just the content they are looking for, and get specific results, tied to an app they can download. And because the result incorporates enough context, the user isn't just left to search within the new app, but is taken right to the content within the app once it downloads.

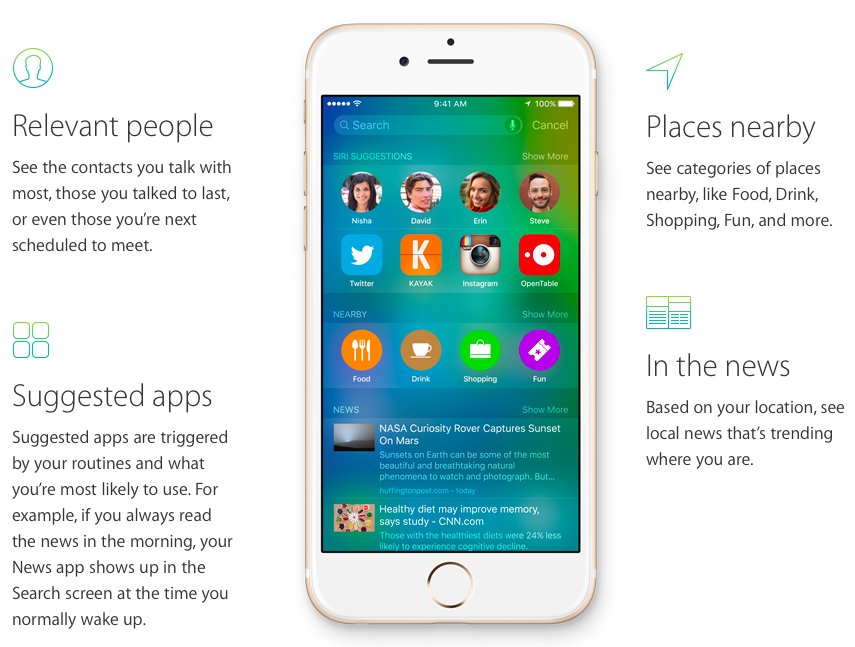

This opens the door for much more natural language search, as well as Intelligent Spotlight Suggestions that can anticipate what a user may be interested in by context, location and patterns of behavior. Apple also provides developer tools to make search results rich and actionable, supporting result listings that include images, audio, video, ratings, and prices, with buttons to perform tasks such as dialing an phone number (for an Airbnb listing), presenting a map (of a business contact), or playing media content (for a movie trailer within an app, or a song within iTunes).

Augmenting these two index populating mechanisms is a third: Web Markup. This allows web site administrators to reference their iOS app from the web, enabling Applebots to pick up deep links to apps and also add these to its index. That allows users to search for content in Safari and see results that can open natively within an app.

Because Apple is indexing in-app content for its search results, it can more easily suppress "Search Engine Optimization" malicious content or link spamming, as relevancy is tied to user engagement. If few users find a search result worthwhile, it can fade from relevance.

Apple follows Google Now, with a twist

Many of the new search-related features Apple debuted for iOS 9 and OS X El Capitan bear a strong resemblance to some of predictive search features first introduced by Google starting back in 2012 as part of Android 4.1, branded as "Google Now."

Since then, Google has introduced "app indexing," a related feature designed to make the company's web-style search more relevant to mobile users by delivering results that can open within local apps. For example, a recipe might open within a cookbook app, rather than just presenting the same information on a web page or dumping users into the app to find the recipe on their own. The most profound difference between the two companies' approach to in-app search is that Apple does not monetize its search with ads

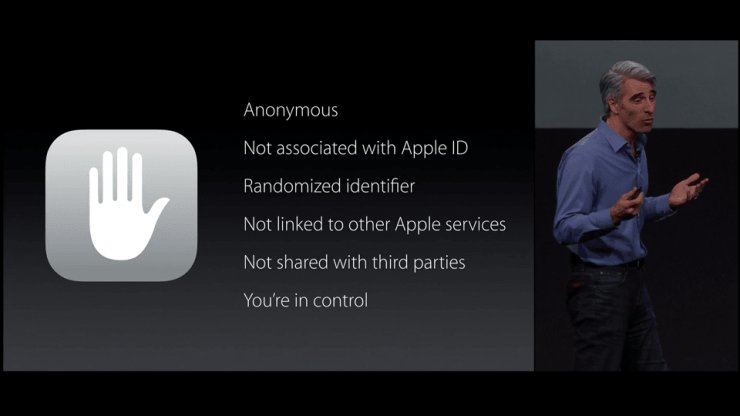

The most profound difference between the two companies' approach to in-app search is that Apple does not monetize its search with ads, and therefore has no need to capture and store users' data and behaviors for future profiling, tied to a persistent user and device identifier that individuals can't easily remove.

Apple's head of software platforms Craig Federighi emphasized in his WWDC presentation that the new predictive, proactive search services in iOS and OS X would be anonymous, not linked to the user's Apple ID or to other Apple services, use a randomized identifier, and not share data with third parties.

Is Apple protecting user privacy to a fault?

A flurry of pundits and analysts have suggested that Apple's "privacy by design" approach to in-app, proactive Intelligent search puts the company at a disadvantage to Google.

For example, an article by Kif Leswing for International Business Times worried that there was a "distinct possibility" that Apple's new search services unveiled at WWDC "may turn out to be inferior to Google Now because of the simple reason that Apple doesn't collect as much data as Google."

The article cited IHS technology analyst Ian Fogg as saying, "Essentially what Apple is aspiring to do is deliver an experience as smart as the opposition while having one hand tied behind their back."

The piece even imagined that Apple's policy of encrypting Mac and iOS users' Messages— rather than collecting users' conversations for analysis— was "a win for user privacy, but a loss for Apple's technological potential."

The problem with this logic is that Apple's iOS devices have plenty of access to private data (including the user's contacts, their precise location and even the context within a document they are working on) that they can use to shape search results or suggestions, without ever reporting, recording or linking that data to an individual in a database. In fact, much of iOS 9's Intelligence is grounded in private data, it just keeps it private.

Two companies, motivated by money in two different directions

Google's appetite for identifiable user information linking across all of its properties, platforms and services is directly tied to its primary revenue source, the same way Apple's desire to make faster, thinner, more elegant hardware is directly tied to its primary income source. Nowhere is that contrast more obvious than in Apple's efforts to erase the persistent links between advertising identifiers, the identity of end users and the unique hardware identifier of their devices.

Apple's Spotlight search uses a temporary, anonymous identifier that refreshes every fifteen minutes. Under iOS 8, devices also randomize their hardware MAC address so that WiFi network scanners can't maintain an identifying lock on users over time. And in iOS 7, Apple introduced a user-erasable Advertiser ID and began enforcing App Store policies that prevented apps from tracking users for any purpose other than to display relevant advertising, while enabling users to opt out of even that by reseting their Ad ID at anytime.

While Google has copied elements of the iOS Advertising ID in principle, and also offers some controls to users to opt out of its services, by default the company collects and correlates incredible amounts of data that is personally identifiable by design. In fact, the entire intent of Google+, an initiative the company has aggressively forced upon its users, is to build a persistent profile of as much personally identifiable information as possible.

That's not for relevant search results; it's aimed at optimizing extremely targeted advertising.

Google outlines that it collects and links lots of personal data

Google's privacy policy states, "We collect information about the services that you use and how you use them, like when you watch a video on YouTube, visit a website that uses our advertising services, or view and interact with our ads and content," adding in a footnote, "this includes information like your usage data and preferences, Gmail messages, G+ profile, photos, videos, browsing history, map searches, docs, or other Google-hosted content."

It adds, "We collect device-specific information (such as your hardware model, operating system version, unique device identifiers, and mobile network information including phone number). Google may associate your device identifiers or phone number with your Google Account."We collect device-specific information (such as your hardware model, operating system version, unique device identifiers, and mobile network information including phone number). Google may associate your device identifiers or phone number with your Google Account

The company explains, "When you use our services or view content provided by Google, we automatically collect and store certain information in server logs. This includes: details of how you used our service, such as your search queries; telephony log information like your phone number, calling-party number, forwarding numbers, time and date of calls, duration of calls, SMS routing information and types of calls; Internet protocol address; device event information such as crashes, system activity, hardware settings, browser type, browser language, the date and time of your request and referral URL; cookies that may uniquely identify your browser or your Google Account.

"When you use Google services, we may collect and process information about your actual location. We use various technologies to determine location, including IP address, GPS, and other sensors..." the page continues in detail about the company's use of 'unique application numbers, local storage, cookies and similar technologies.'

"Information we collect when you are signed in to Google may be associated with your Google Account," the company states, adding, "We may use the name you provide for your Google Profile across all of the services we offer that require a Google Account. In addition, we may replace past names associated with your Google Account so that you are represented consistently across all our services. If other users already have your email, or other information that identifies you, we may show them your publicly visible Google Profile information, such as your name and photo."

"If you have a Google Account, we may display your Profile name, Profile photo, and actions you take on Google or on third-party applications connected to your Google Account (such as +1's, reviews you write and comments you post) in our services, including displaying in ads and other commercial contexts."

Just from those excepts, that's a lot of data, likely far more than most users are aware is being stored about them.

Search— and even relevant ads— don't require a surrendering of privacy

Given the frequent and serious security lapses of Google's Android platform, it's not just Google's storage of vast networks of private, personally identified information that its user have to consider. If it's that easy for Google to collect massive amounts of data on its users, imagine how easy it is for third parties— including rogue malware app developers— to intercept, collect and link data using many of the same mechanisms.

What Apple's own search services are showing is that robust, rich, relevant search results don't necessitate massive data collection programs, unless they sit upon a business model of advertising that does. Additionally, Apple is also showing with iAd that even effective, high value advertising doesn't require massive data collection of personal, device specific private data.

Apple is further showing that it increasingly is not dependent upon Google for its search, maps, cloud storage or advertising services. That's a big problem for Google, because its 75 percent of its mobile advertising revenue directly relies on Apple. That's particularly an issue as its greater dependance upon desktop PCs continues to plateau.

What remains to be seen is how many users can be convinced that their privacy doesn't matter, when the overt lack of privacy on Android increasingly offers few unique advantages over the enhanced privacy Apple secures for its customers on iOS.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Michael Stroup

Michael Stroup

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele