A report chronicling Apple's history of handling government data requests says the company received, and willingly complied with, its first court order to help unlock an iPhone in 2008. Apple continued on that path until around 2014, when the wider tech industry began clamping down on product security in light of revelations regarding government snooping operations.

According to a Wall Street Journal report published Thursday, the first court order requesting Apple access one of its own devices is believed to date back to the prosecution of child sex offenders Amanda and Christopher Jansen in 2008, approximately one year after iPhone debuted.

The Watertown, N.Y., case is thought to be the progenitor of numerous FBI requests for iPhone unlock assistance, which Apple now actively resists. A Justice Department filing lodged last year in a separate Brooklyn case involving a drug trafficker's iPhone details the 2008 prosecution that relied in part on evidence recovered from an impounded iPhone. Specifically, prosecutor Lisa Fletcher said in her 2008 request to Apple that no statute exists to compel assistance from a company like Apple. Foreshadowing the FBI's recent San Bernardino investigation, Fletcher did point out that the court could invoke the All Writs Act to force Apple's compliance.

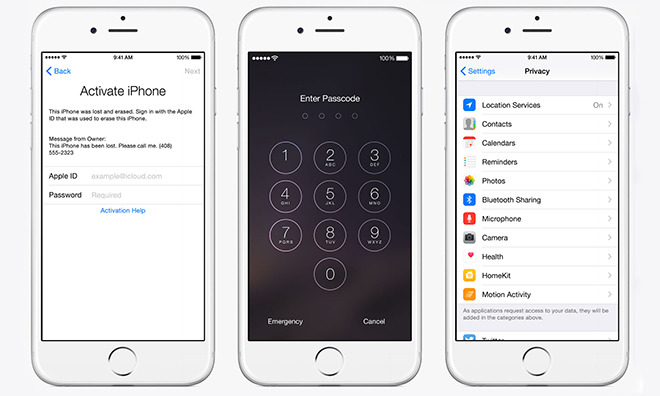

Unlike San Bernardino, however, Apple said it would offer assistance as long as the Justice Department furnished a proper court order. Perhaps ironically, Apple helped draft the order that was then signed by U.S. Magistrate Judge George Lowe, thus enabling the company to bring the target device back to California and bypass its passcode in front of a New York State Police investigator, the report said.

In all, Apple helped the government access more than 70 devices without much public ado, certainly nothing close to the vehement opposition displayed in San Bernardino.

When the Watertown iPhone was accessed, smartphones were still niche devices; handling of government data requests was virgin territory for the courts and manufacturers alike. As consumer interest in smartphones grew, in large part thanks to Apple's iPhone, so did the amount of data being produced and stored on these devices.

Rapid smartphone proliferation left law enforcement agencies like the FBI with little choice but to adapt decades of traditional physical evidence gathering techniques to a world ruled by digital information. Attorney General Loretta Lynch in March said data procurement is now a key facet of nearly all modern investigations, and law enforcement officials might, at times, need to seek assistance from device manufacturers. Initially, Apple and other tech companies willingly complied with data requests — not necessarily assistance in unlocking hardware — as long as they came with a proper warrant.

Everything changed when former NSA contractor Edward Snowden leaked sensitive documents detailing an surreptitious government surveillance program in 2013. In the ensuing fallout, tech companies felt pressure to tighten security as public outrage boiled over, resulting in the implementation of advanced encryption protocols.

Apple, with an iPhone customer base numbering into the hundreds of millions, was particularly sensitive to Snowden's disclosure. Sources familiar with the matter claim top Apple executives resolved to bolster iPhone encryption in 2014, the NYT reports. That effort bore fruit in iOS 8, the first operating system with encryption even Apple couldn't crack.

Over the past few years, government agencies have employed a variety of data extraction techniques, either developed in house or purchased from forensics tool vendors, in a cat-and-mouse game with consumer tech companies that continues today. In 2014, however, Apple obsoleted a number of existing methods when it introduced on-device encryption with the A7 SoC, a processor that features Secure Enclave technology.

The broader encryption issue came to a head in February when the FBI filed an All Writs motion to compel Apple's assistance in unlocking an iPhone tied to San Bernardino terror suspect Syed Rizwan Farook. Apple resisted the order, arguing that hundreds of millions of iOS devices would be made vulnerable by the requested software workaround.

Last month, an unnamed third party came forward with a viable data extraction method, prompting the FBI to withdraw its legal pursuit. The agency has reportedly shared details of the exploit with high-ranking U.S. senators, but has no current plans to disclose the same information to Apple. FBI officials refuse to comment on whether or not data gleaned from Farook's iPhone is useful to its investigation.

Most recently, FBI Director James Comey today said the working exploit is limited to iPhone 5c models and older, suggesting Apple might soon find itself back in court fighting off another AWA order.

Mikey Campbell

Mikey Campbell

-xl-m.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

6 Comments

Back in 2008 Apple had the ability to unlock phones so there was no issue.

There don't have a problem with helping law enforcement when they have the ability.

It's a whole different issue when law enforcement demands that they do hacking work for the government, work to break their own product or design and build in a security weakness to give the government a backdoor. Doing these things is unreasonable and puts everyone's security and privacy in danger. Unlocking a phone help law enforcement when you have the key is not unreasonable.

Apple has never unlocked iPhones for anyone. http://techcrunch.com/2016/02/18/no-apple-has-not-unlocked-70-iphones-for-law-enforcement/

So the bad guy enabled an optional passcode, available on the 3G anyway? Not entirely shocked.