Why Apple is betting on Light Peak with Intel: a love story

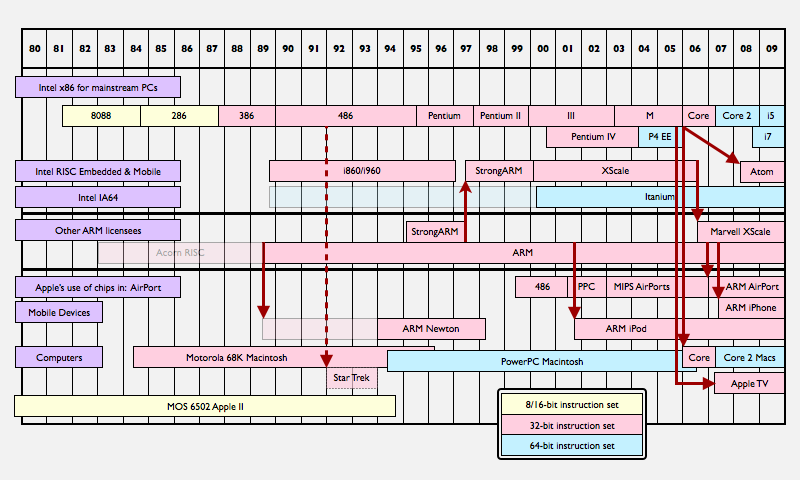

Apple and Intel rarely crossed paths in their early days. In the 80s, Apple used chips from MOS and Motorola while Intel powered the IBM PC juggernaut. In the 90s, Apple worked with Acorn to deliver mobile ARM processors for its Newton Message Pad, and then with IBM and Motorola on Power PC, a modern new architecture aimed squarely at replacing the Intel x86 PC.

Apart from the secretive Star Trek Project, a brief collaboration exploring the idea of porting the classic Mac OS to Intel in 1992-1993, Apple rarely ever even caught Intel's eye. Then suddenly things changed.

In the late 90s, Intel failed miserably in trying to get its new 64-bit Itanium off the ground, only to run into a dead end with its Pentium 4, which ran blazing hot but only delivered lukewarm performance. Meanwhile, PowerPC was largely only finding real success in embedded applications, leaving Apple ignored by its increasingly disinterested chip fab partners.

Apple wanted a strong provider ready to flex some muscles on its behalf, and Intel desired a sexy darling of industry it could parade into market. Thanks to the technology it had acquired from NeXT in 1997, Apple could now run its Mac OS platform on virtually any chip architecture and still support existing third party apps with relatively minimal changes. Apple and Intel were ready to look at each other in a whole new light.

Is this thing still on?

To the casual observer, Apple's sudden romance with Intel in 2005 (and the resulting shotgun wedding of Mac OS X with Intel's x86 Core processors in the transition that began in 2006) has since lost some of its initial warmth. Outside of its Intel-based Macs and Apple TV, Apple has retained the use of ARM processors in its iPod, iPhone and AirPort base station product families. This has been bad news for Intel's low power, x86-compatible Atom chips, which the company hoped Apple would grow to love in place of ARM.

Sources familiar with Apple's plans say the company decided against Atom in favor of continued use of ARM processors in its mobile devices due to the better power management and maturity of the ARM architecture compared to Intel's fledgeling Atom chips. But rather than waiting around for Atom to catch up with ARM, Apple has invested deeply in building up an ARM's race to power its future hardware.

In April of 2008 Apple acquired fabless chip designer PA Semi, with the expressed intention to develop new mobile chips for use in the iPhone and iPod line. That purchase brought a highly esteemed crew of veteran chip designers under Apple's wing, including PA Semi founder Dan Dobberpuhl, who developed DEC's trailblazing Alpha followed by its highly efficient StrongARM mobile processors.

Somewhat ironically, Intel had acquired StrongARM from DEC in 1998, rebranded it as Xscale, and invested fantastic sums of money into it, only to then sell the chip division at a massive loss to Marvell in late 2006, right before Apple signaled its intention to dive into smartphones and other sophisticated mobile devices like the iPod touch. (Incidentally, Apple had canceled its StrongARM-based Newton handhelds in 1998 just as Intel jumped into the mobile chip business).

Intel, having rid itself of its poorly-performing mobile chip business that has licensed technology from ARM, instead focused on converting its x86 processor family for use in mobile applications in a project that resulted in Atom. Those chips weren't anywhere near ready for the iPhone, so Apple continued along its ARM-centric roadmap it had been on since the original iPod in 2001.

Apple plays the field

On the heels of its 2008 PA Semi acquisition, Apple also fleshed out other new ARM-related deals. Throughout 2008, AppleInsider reported and then confirmed that Apple was the 'mysterious licensee' involved in quietly lining up broad rights to use Imagination Technologies's PowerVR mobile graphics technology, the popular GPU complement to ARM CPU cores in "System on a Chip" processors designed for for mobile devices.

Apple has also hired a variety of other chip gurus, including a key developer of IBM's POWER architecture, Mark Papermaster, last fall; Bob Drebin, who formerly served as chief technology officer of AMD's graphics products group; and earlier this spring, Raja Koduri, who initially replaced Drebin's post at AMD before following him to join Apple.

It would appear that Apple is asserting its independence from Intel, a reversal of Apple's 2005 decision to liquidate its in-house VLSI engineering talent in favor of delegating all of its chipset design work to Intel. In addition to its own in-house work aimed at mobile CPUs, Apple also forged a partnership with NVIDIA last fall to migrate its Macs from Intel's chipsets to NVIDIA's 9400M integrated chipset with advanced graphics, a choice that helped inflame tensions between Intel and NVIDIA over the pairing of NVIDIA's chipsets with future generations of Intel's CPUs.

At the same time, shortly after the PA Semi purchase was announced, Steve Jobs told the Wall Street Journal "We have a great partnership with Intel. We expect that to continue forever," and added, "We’re very happy with Intel."

On page 2 of 3: Intel's fatal attraction.

Apple's desire to maintain an open relationship with Intel has been a source of frustration and jealously for the chip maker. Last fall, Intel's Shane Wall and Pankaj Kedia made dismissive remarks about the iPhone and its ARM CPU at the company's Intel Developer Forum.

"If you want to run full internet, you're going to have to run an Intel-based architecture," Wall told the gathering of engineers. He said the "iPhone struggles" when tasked with running "any sort of application that requires any horse power."

"The shortcomings of the iPhone are not because of Apple," Kedia added. "The shortcomings of the iPhone have come from ARM." Other handset vendors face the same problem Kedia said, adding that their smartphones are "not very smart" because "they use ARM."

The comments were met with an apologetic correction from Anand Chandrasekher, Intel's senior vice president and general manager of its ultra-mobility products group, who "acknowledged that Intel's low-power Atom processor does not yet match the battery life characteristics of the ARM processor in a phone form factor and that, while Intel does have plans on the books to get us to be competitive in the ultra low power domain - we are not there as yet. Secondly, Apple's iPhone offering is an extremely innovative product that enables new and exciting market opportunities. The statements made in Taiwan were inappropriate, and Intel representatives should not have been commenting on specific customer designs."

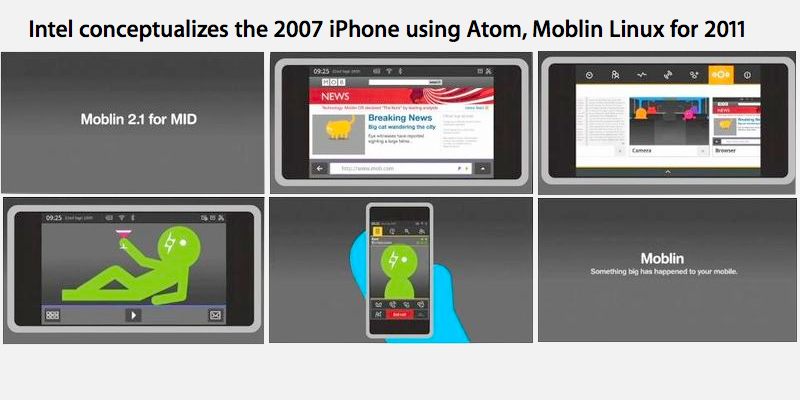

At this year's IDF event held just last week however, Intel CEO Paul Otellini spoke of the future of Atom-based mobile devices in the 2011 timeframe as if the 2007 iPhone hadn't ever existed, presenting a video portraying a futuristic device looking a lot like a simplified iPhone but using a future Atom chip and running Moblin, a Linux distro Intel began promoting in 2007.

This summer, Intel also paid a whopping $884 million to acquire Wind River Systems, a company which sells VxWorks (a proprietary real time embedded operating system that runs on both x86 and ARM) and its Wind River Linux distro (most famous for being the software that was supposed to power the aborted Palm Foleo).

Intel now owns three operating systems for Atom, but it's pretty clear that the company really lusts after Apple's iPhone OS on its Atom chips. Intel's efforts to popularize its Atom chips without Apple's help looks a bit like a shotgun attempt to the enter the mobile space any way possible so that someday Apple will have a reason to reconsider.

Intel follows Apple into the post-PC world

Unlike the generic PC market, smartphones and mobile devices aren't at all bound to Intel's x86 platform. The vast majority all run ARM, including Palm, Android, Symbian, Windows Mobile, BlackBerry OS and Apple's iPhone and iPods. Those devices also have no compelling reason to run on an x86 processor, unlike netbooks using the desktop version of Windows, which is tied to the x86 CPU platform.

In addition to predicting the iPhone years after Apple shipped it, Otellini also seemed to be repeating another idea that Steve Jobs presented back in 2007, when Apple Computer announced it was dropping the Computer to become just Apple, Inc. Otellini's version was worded as, "Intel is going to be using the continuum opportunity as an ability to move from personal computers as a company to personal computing." If Intel wants to stay on top of computing as it moves from the PC toward mobile devices, it has to get somebody significant interested in Atom.

Intel isn't bothering to court Windows Mobile, it knows it has little chance with Symbian and other typical smartphone operating systems, and it looks a lot like nobody else can sell a general purpose Internet device outside of Apple. Fortunately, Intel has something Apple is interested in, and that might possibly give Apple additional reasons to consider hawking Atom chips in the future.

On page 3 of 3: Apple, Intel and the ports business.

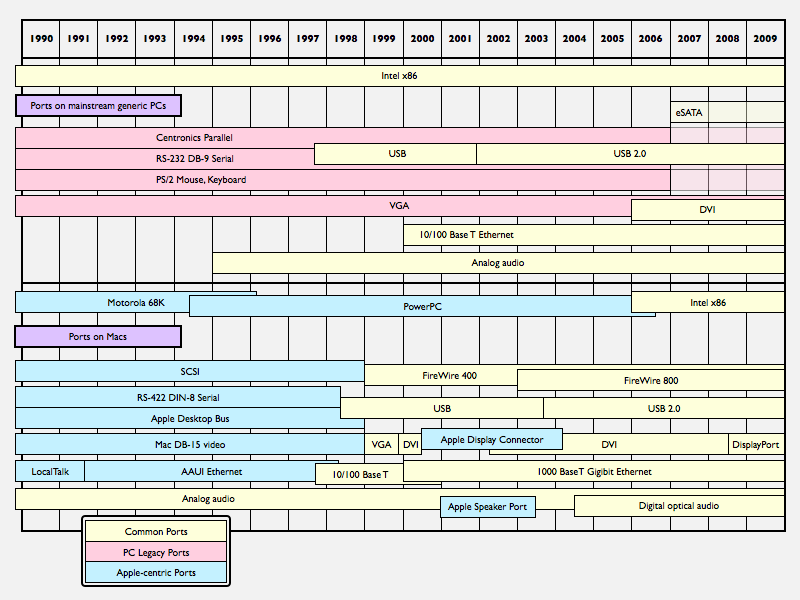

What Intel has and Apple lacks on its own is the ability to garner widespread adoption of new cabling schemes and the economies of scale that follow. Back in the 80s, Apple largely just ignored the generic PC world and its third-rate port specifications. While PCs shipped with RS-232 serial ports and Centronics parallel ports for printing and slow disk drives, Apple gave its Macs an improved RS-422 serial port that was backwardly compatible but offered the ability to accommodate AppleTalk/LocalTalk networking.

On the other hand, Apple also adopted the high performance SCSI interface for hard drives and printers and scanners, something that was deemed too luxuriously expensive for mainstream PCs. That subsequently kept SCSI and its interface support chips relatively expensive to manufacture.

Steve Wozniak's Apple Desktop Bus was adopted by Apple in 1986 for connecting together a variety of input devices and serial peripherals, from keyboards and mice to stylus tablets, barcode scanners and video cameras. Despite some use outside Apple by Sun and NeXT, ADB similarly never caught on among generic PCs, which continued using two PS/2 connectors, one for the keyboard and one for the mouse. That similarly helped keep ADB peripherals relatively expensive.

Apple then developed FireWire as a high speed cabling system that could accommodate the future needs of digital video and replace SCSI with simpler cabling. This too was slow to broadly catch on among PC makers. Intel delivered its own USB specification as a slow, ADB-like peripheral connection standard to replace RS-232 serial, Centronics parallel, and PS/2 connectors on PCs. While it didn't initially gain much attention among PC users, Apple adopted USB as a way to jettison both ADB and serial ports on the iMac, and kickstarted the market for low speed USB peripherals.

Intel then upgraded the USB standard to 2.0, a move that encroached upon the performance of FireWire (without actually delivering many of the features FireWire was designed to provide). This effectively killed any mainstream market for FireWire outside of niche markets, and again subsequently kept FireWire relatively expensive to implement.

Stronger together

On their own, Apple and Intel had limited success in promoting new standards into the mainstream; together, the pair seemed to be very complimentary partners. Intel acts as the establishment insider, holding down prices with high volume mainstream production, while Apple serves as the vanguard, pushing new technologies into an industry notoriously resistant to change.

Things don't always happen according to plans, however. In 2005, Apple and Intel began working with other partners on a replacement for VGA and DVI video ports which would complement the HDMI standard emerging in home theater applications. The new specification, called Unified Display Interface, intended to essentially be a variant of HDMI for use in computer applications.

Instead, PC makers such as Dell, HP, and Lenovo began adopting VESA's competing DisplayPort specification instead. Realizing that its main customers were lined up behind DisplayPort, Intel pulled out of UDI and backed DisplayPort in 2007. Apple jumped on the DisplayPort bandwagon last fall in its new line of unibody MacBooks.

With Light Peak, Apple and Intel are investing in a major project to deliver a unified new high speed cabling system that remains backwardly compatible with existing protocols and leverages state of the art technology while hitting a mainstream price point. Getting Light Peak to work requires a joint fusion of the core competencies of both Apple and Intel. Its success will benefit the entire industry, and solve a number of existing problems.

Port overload

Many port specifications overlap with others enough to make them redundant for mainstream users. For example, with USB and FireWire already on most Macs, Apple has ignored eSATA, a way to connect external SATA hard drives directly. Even USB and FireWire overlap enough to make it impractical to include both in some applications; Apple eventually dropped FireWire on its iPod line when USB 2.0 became popular enough to use and cheap enough to make FireWire a luxury. Apple also attempted to drop FireWire on its entry-level MacBooks, but recanted after customers complained.

In some cases, multiple signaling protocols can be combined in a single port. For example, DVI ports also supplied analog VGA pins. Apple also combined the MacBook's analog audio jacks with mini-Toslink digital optical ports to create a hybrid jack that can work with either kind of cable. The iPod dock connector combines component and composite video signals, audio, USB, and simple serial signaling into a single port. Apple once bundled DVI, USB and power together on a single cable called Apple Display Connector for its Cinema Displays. The company even developed a specification for supplying FireWire signaling over the same RJ-45 connector used for Ethernet networking, although it hasn't ever shipped on a production Mac.

With Light Peak, Apple asked Intel to develop a single data port that could supply multiple, high speed streams of data capable of carrying virtually any type of signaling: networking protocols like Ethernet and Fibre Channel; standard audio and video signals such as S/PDIF, HDMI and DisplayPort; and serial interfaces such as FireWire, USB, and eSATA. Using optical signaling, Light Peak can achieve very high data speeds over relatively long cables that can be very thin; copper cables have problems with signal attenuation, electromagnetic interference, and bulk.

Light Peak offers the capacity to upgrade existing signaling protocols to work over high speed optical cables driven down in cost by volume production. Additionally, with any type of signal available through a single optical port, both notebooks and smaller mobile devices can shed today's overlapping variety of limited capacity ports for a single pipe that delivers virtually any kind of data at extremely high speeds. This would allow a laptop to plug into a monitor via one thin cable, and then allow the display to offer standard jacks such as USB and Ethernet networking. Currently, Apple's displays need to plug into both DisplayPort/DVI and USB, which together results in a larger, more complex and expensive cable.

Teamed up with Intel, Apple can get a cheaper connector for its future systems, with development costs spread across the industry; Intel can get a partner ready to promote and rapidly deploy the new standard. Additionally, by working with Apple to develop a low-power mobile version of Light Peak, Intel can stay in the mobile business and hopefully someday impress Apple with its roadmap for Atom. Whether Atom can ever catch up to and surpass the industry momentum behind ARM remains to be seen.

Daniel Eran Dilger is the author of "Snow Leopard Server (Developer Reference)," a new book from Wiley available now for pre-order at a special price from Amazon.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

113 Comments

Very Cosmopolitan!

Read the article on CNET today. Their sources tell that this is purely Intel's tech.

Hahah super fast data transfer here we come lol. Can't wait as time capsule backup will be sooo fast

back in the 1990's Intel made money on the early adopters. they would release a new CPU generation that ran on existing motherboards. 6 months later they would release the new motherboards and chipsets. some people would spend almost $1000 on just the CPU to have it first.

in the current decade everyone wants a laptop. Apple makes almost all their computers with laptop parts and the enthusiast market is so so. So Apple and intel get to together and Intel now has a source of big margins since PC margins are falling every year.

Intel entered into the motherboard market in the 1990's but still doesn't control the entire board. I guess light peak is an attempt to control the entire PC except for the case.

$600 PC from Dell, most of the money goes to Microsoft and Intel.

USB was nice and cheap. WIth this it looks like you will need a separate LightPeak router to plug everything else in. until it comes out i really don't see the point of being the first one to buy it

This new innovation, if they roll it out, sounds very promising.