Articles in this series:

Inside Google's Android and Apple's iPhone OS as core platforms

Inside Google's Android and Apple's iPhone OS as business models

Inside Google's Android and Apple's iPhone OS as advancing technology

Inside Google's Android and Apple's iPhone OS as software markets

Android vs. iPhone: Restrictions vs security

Platform vendors, in this case Apple and Google, have to balance various factors to create a desirable environment for consumers. On one hand, users want a phone that works reliably and does everything they might want it to do without artificial restrictions or limitations put in place by the vendor.

At the same time, users also want a progressive platform that offers them new features as they become available and want to be protected from security threats such as malicious viruses causing data theft or loss, annoying adware, spyware and spam.

The problem is that adding lots of new features tends to result in bloat, slow performance, and the inadvertent introduction of bugs, while imposing vigilant security measures results in a certain amount of inconvenience and limitation for users. Balancing these factors is an engineering art. How well Apple and Google can do this is closely tied to the business model of their smartphone platforms.

Business model: iPhone

Apple's iPhone platform has a pretty simple business model: everything is run under the tight direction of one company to deliver what it hopes to be the most desirable offering possible, in order to sell the most iPhones to users.

The iPhone's software platform is knit into Apple's own hardware design and is tightly integrated with iTunes for setup, software updates, backups, media syncing, application management, and Apple's optional MobileMe cloud sync services.

The iPhone is exclusively tied to official mobile providers who must agree to certain user-friendly concessions (such as supporting iTunes rather than pushing their own expensive ringtones and music services and software). However, Apple's carrier deals also currently limit users' options in many markets such as the US, where the iPhone can only be used on AT&T's network.

Apple also maintains rigid control over where the iPhone is sold, and manages nearly all support issues itself. There's absolutely no passing the buck on user troubleshooting, hardware problems, or software issues like security flaws or poor performance. If there's a problem with the iPhone, it's squarely Apple's fault.

On the other hand, you can't get the iPhone OS from any other source, you're not allowed to modify the core software, you can't install apps that Apple determines to be of poor quality, incompatible with its design goals (including background operation of third party apps), or damaging to its platform (such as Adobe Flash) unless you take it upon yourself to hack the iPhone via a jailbreak, something that Apple discourages and works to prevent. In some cases there's simply no way to shoehorn in features that Apple doesn't want to support or allow.

Business model: Android

Google's business model is more complex in some respects and yet also simpler. The company doesn't make money selling phone hardware or even in licensing the core Android software (which is free and open source). Google makes money selling ads and tracking users' preferences, which it does through its own Google-branded, bundled apps (which are not free nor open source).

This results in Android software only being as tightly integrated with hardware as third party vendors might choose to deliver (or are capable of producing). Hardware makers can add features that Google doesn't fully support (such as multitouch gestures or unique user interfaces), and Android can offer features that aren't implemented in certain hardware devices (such as compass support).

Unlike the iPhone and iTunes, Android phones aren't integrated into a central desktop app of any kind, so users with different mobile providers and buying from different hardware makers will all face unique configuration circumstances because setup, updates, backups, media sync, software management and cloud sync services can all be implemented in different ways on different Android-based products.

How exclusively a specific Android phone is tied to a given provider is also negotiable. Some models may be unlocked and used virtually anywhere, while others are locked down just as tight as a Verizon feature phone, with disabled hardware and non-removable VCast.

There's little leverage for Google to seek concessions from mobile providers the way Apple does, as the company is not the hardware vendor. Android is supposed to arrive on a flurry of new devices from various makers early next year, but nearly every vendor is promising to deliver a customized experience to differentiate their offering, making the Android platform nothing similar to the cohesive, global experience of the iPhone (or for that matter, Windows on the PC).

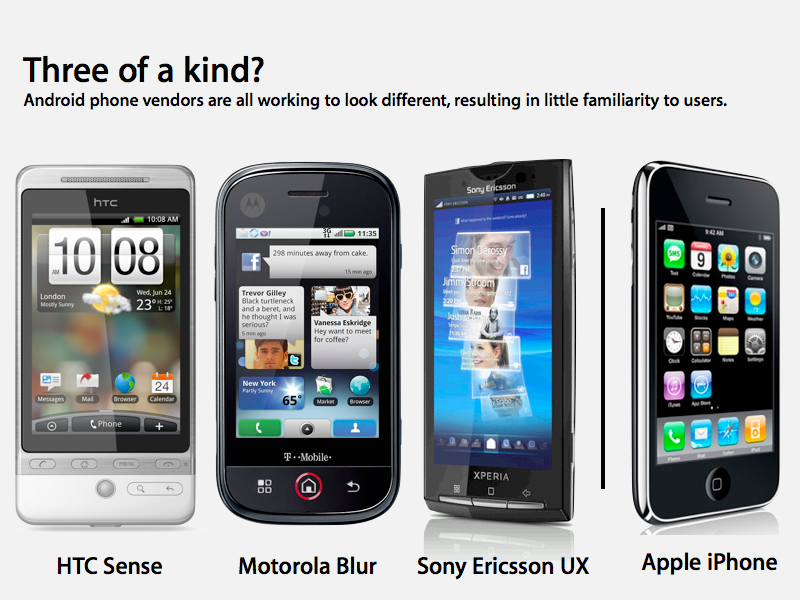

HTC markets its unique look and feel as Sense, Motorola sells its own user interface as MotoBlur, and Sony Ericsson is calling its interface for the upcoming Xperia X10 "Rachael" or UX. Other vendors are guaranteed to create their own layers of unique user interfaces.

Imagine if Dell and HP made Windows PCs with completely different desktops and user apps: would most users even recognize them to be Windows? It would be more like Linux PCs, where there's so many choices that no significant number of users makes any one of them, resulting in little commonality for software developers, user training or support resources to target. Microsoft worked very hard to force PC makers to present a unified desktop look so that consumers would know to ask for Windows, and so PC makers could present a familiar product with known features.

Many Android users won't even realize they're using an Android phone, and won't even see that much familiarity between it an an Android phone from another vendor or mobile provider. That's because there's no standardized branding, no enforced minimum feature set, no consistent user interface nor any standards on how things look, how touch gestures should work, or where physical buttons are.

The brand that wasn't there

Unlike the iPhone, Android presents no significant limitations on which apps Google will list in Android's software market, but there's also no requirement for software signing or other security restrictions in place to prevent users from being spied upon or attacked by malicious apps or hassled by adware, nor any app quality guidelines.

And while customers might not have any complaints with Google's lax brand management of Android, it will impact how the market receives Android products, and in turn, how widely adopted and competitive Android phones are, and subsequently how much software is available for the platform.

As an example, while Apple has one carefully-guarded iPhone brand worldwide, Google allows any device to call itself Android. If one vendor makes a terrible Android phone, it has the ability to taint the perception of the Android platform itself. This is another reason why Microsoft worked so hard to create a minimum standard and consistent desktop for Windows PCs.

Google has no experience in managing a platform, and does not appear to have even examined what factors helped make Microsoft successful on the PC. But Google also seems to have no sense of brand management, a curious problem for a company with a name that has become the verb for web search and with widely known products including Gmail

Google doesn't seem to be advertising the Android brand to mainstream consumers at all. Instead, it allows its partners to co-opt the brand in various ways. For example, Verizon is now branding specific Android models it carries as Droid; those same hardware devices can be from different vendors ("the Droid" is made by Motorola, while "Droid Eris" is an HTC product running a completely different user interface on an older version of Android and running on slower hardware), and those models must be named something else on other providers (Motorola's Droid will be sold as Milestone elsewhere, and the Droid Eris is HTC's Hero on other carriers).

This completely stifles any ability for Motorola to market its new Android phone globally, or for HTC to leverage the goodwill it creates with one provider to other markets. It also hijacks users' perception of Android to associate it with Verizon, despite the fact that the first Android phone sold via T-Mobile, and that all US mobile companies will likely be selling Android phones next year.

Imaging Apple allowing some carriers to exclusively sell the iPhone as "iPho" and the brand confusion that would result. Or imagine Apple trying to market the iPhone under completely different names in different markets globally. The whole point of a brand is to create awareness of a product and establish a trade name that customers recognize and associate with a strong reputation.

Google is allowing its partners to fight over the Android brand, invent competing and confusing sub-brands, and to create different experiences associated with its brand. The result will be a series of short lived flashes that fail to leave any mark in the minds of consumers, the same way LG's Prada, Vu, Viewity, Venus, Voyager, enV Touch, Cookie, Dare, Secret, Arena, Xenon, Cyon, Shine, Incite, and Renoir (all identical or very similar touchscreen models sold in different markets or by different providers) have failed to establish any sort of competitive mindshare against the iPhone during the same period of time on the market.

If there's a problem with an Android phone, users might be pointed at their mobile provider, or at the hardware vendor, or to the Android open source community, none of whom can take full responsibility for the whole widget even if they wanted to, and none of them have any real reason to want to. This results in Android being a fantastic platform for hobbyists and hackers, but one which presents series of terrible scenarios for mainstream users who want things to just work consistently and intuitively, with adequate and appropriate security and yet still offer plenty of viable commercial potential without compromising convenience and usability.

Software integration in consumer devices

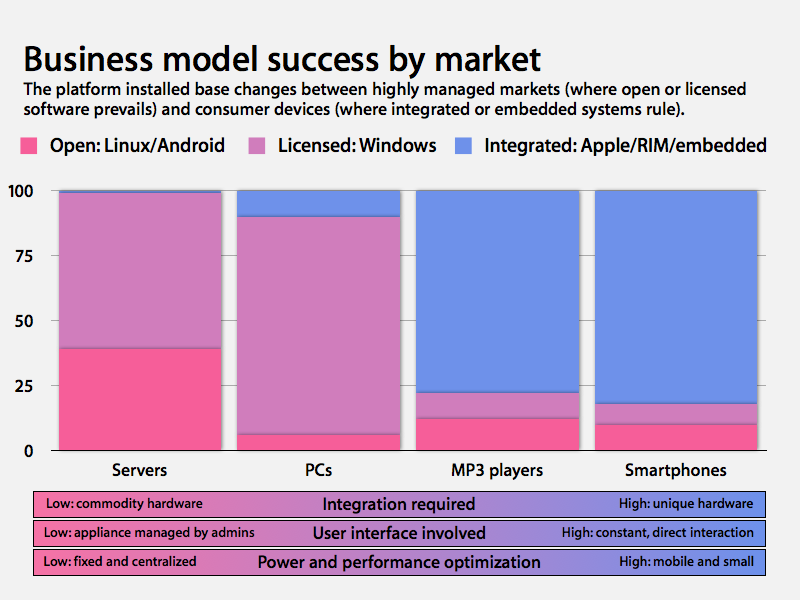

Many of the issues negatively affecting Android are related to Google's business model, which happens to be very similar to Microsoft's Windows Mobile and PlaysForSure. Unlike its very successful Windows on the PC, Microsoft's efforts in mobile devices have been colossal failures, largely because the hardware/software integration issues that impact PC users are not nearly as critical as those affecting handheld devices that involve more direct use and include power management, performance and user interface issues that require much more integration work than desktop PCs.

Microsoft's software licensing model works best among servers and PCs where users are supported by professional IT staff, the same place Linux is most popular. In PCs, Microsoft's control over the user experience helps it edge out any real encroachment from Linux among mainstream users, but has not stopped Apple from eating into PC market share with its more integrated, cohesive Macs. However, in mobile devices, Apple's strict control of the user experience has enabled it to excel with the iPod and iPhone, two markets that neither Microsoft nor other broadly licensed open software platforms have managed to crack.

The best success story in mobile licensing has been Symbian, but this was largely a partnership between major phone makers who simply shared work on kernel development. Nokia, Sony Ericsson and NTT DoCoMo each maintained its own version of Symbian tightly integrated with that company's phone hardware.

Faced with competition from even more integrated phones from RIM and Apple, Symbian's share has slipped rapidly and dramatically, and Nokia has since worked to turn it into an open source foundation giving away shared code. There is yet no evidence that this will stop Symbian's share of the smartphone market from its slide in the future. The failure of both Windows Mobile and the once widely-licensed Palm OS also provide some perspective on how well this model works in mobile devices.

In addition to their differing business models, Android and the iPhone platform also differ how the core software platforms are developed and advanced, what first party software is bundled with the phone, and what third party software is available after the sale. Upcoming segments will look at how Android and the iPhone compare in these respects.

Prince McLean

Prince McLean

-m.jpg)

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

143 Comments

Gee, a Dilger article that should be entitled "Why Product X Sucks and Apple's Product Y Rocks".

Color me (un) surprised by this sudden turn of events.

iPhone's is proven, Android's has yet to be proven.

Simple as that.

Nope. When OS 3.0 was having issues keeping connections to AT&T's 3G network, I had an Apple store employee tell me the issues were with AT&T and I needed to contact them. I was told the same thing from the Apple phone support.

The problem was subsequently fixed when 3.0.1 was released, so the problem was indeed not with AT&T (at least not soley)

To Apple's credit, this was after a replacement phone was issued and the problem still existed, but to say that Apple takes full responsibility for iPhone issues is disingenuous at best.

Gee, a Dilger article that should be entitled "Why Product X Sucks and Apple's Product Y Rocks".

Color me (un) surprised by this sudden turn of events.

I thought that too.

I looked at the picture and thought "multiple options gives me choice" rather than what that image's title was. I also thought the iPhone OS interface looked a bit tired in comparison.

iPhone's is proven, Android's has yet to be proven.

Simple as that.

You are so correct. Froma consumer level Apple has the race won and just needs to keep updating the iPhone every so often as they have been and no one with come close to their market share.

What I would like to see and purley from a business corporate level is Apple along with AT&T produce a application interface that would let corpoations have limited control over the the platform. To be able to do what can be done with a BB. To be able to remotely manage the iPhone in a simple stand alone solution. That would include being able to handle encryption, changing the PIN, activation, remote wipe. If they did this they sky would be the limit in the Corp environment.

But then things are going pretty well right now!!! :-)