Articles in this series:

Inside Google's Android and Apple's iPhone OS as core platforms

Inside Google's Android and Apple's iPhone OS as business models

Inside Google's Android and Apple's iPhone OS as advancing technology

Inside Google's Android and Apple's iPhone OS as software markets

Previous articles in this series have examined the underlying core technology and business models used by Apple and Google to create their smartphone platforms. This segment looks at how each platform manages software updates and delivers platform advancement in the form of new operating system features and bundled apps.

Software updates: iPhone

Apple's software updates for the iPhone have followed the pattern of one major new reference release each summer, with regular minor updates released about every month or two in between. All updates install on all versions of the iPhone dating back to 2007. Any software features that require new hardware support are simply missing on earlier models, with abstracted functionality that falls back to work on the available hardware.

After the release of iPhone 2.0, Apple issued a final update for devices running 1.0, primarily for iPod touch users who needed to pay a nominal fee in order to download the 2.0 update. With the introduction of iPhone 3.0, the company signaled the intention to avoid any sort of backwards compatibility conflicts between app developers and the OS version by forcing all third party titles to certify their compatibility with iPhone 3.0.

This helped to cleanly move all iPhone users to 3.0 quickly, negating any reason to maintain support for the previous 2.x platform. This frees Apple from having to split its efforts between different versions, and works to keep the platform feature-progressive and yet simple. Users don't have to think about their phone or app software versions, it all just works.

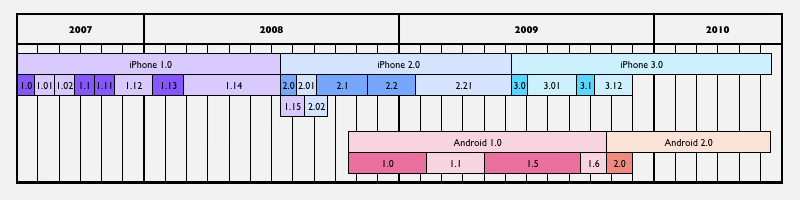

In the chart below, updates introducing significant new features are indicated in darker colors while bug fix and performance improvement releases are lighter. Apple has delivered three or four new feature updates per year, each padded by three or four general improvement updates. In its first year, Android shipped two feature updates and two general improvement updates; that's half the pace Apple set for the iPhone in its first year.

Software updates: Android

Once a new Android update becomes available, users will need to obtain it themselves or wait for their mobile operator to deliver it. Because mobile providers and hardware makers can make significant, proprietary changes to the standard Android software, the platform's users don't all have a single, simple way to install the latest version of Android.

In other words, in order to get the HTC-specific or Verizon-specific or model-specific version of the latest Android release, users will face the same issues that RIM BlackBerry, Symbian, and Windows Mobile users are all familiar with: a waiting game that involves lining up the platform vendor with the hardware vendor and then rollout by the mobile provider.

Sony Ericsson just announced its Xperia X10, a new Android model it expects to release early next year, but says it will ship with Android 1.6 rather than the latest 2.0 version. Verizon's Droid (by Motorola) and Droid Eris (made by HTC) currently ship with Android 2.0 and Android 1.5 respectively.

This is mind boggling to users familiar with Apple's updates, but again it's common practice among other smartphone platforms. Users who want to upgrade to Android 2.0 themselves will have to figure out on their own how to get Sony Ericsson's or HTC's custom user interfaces and other modifications to support their model's unique hardware until the vendor decides to adopt the most recent version. Among other software platforms, this process can take months after an update is originally released.

Additionally, depending on the hardware specifications of a given Android phone, future Android updates that Google releases may or may not install at all, or may require hacking to scale back or drop features so that they fit on the phone.

For example, Google has warned that the original, year-old T-Mobile G1/HTC Dream doesn't have enough built-in memory to accommodate future Android updates. Somewhere along the line, the software platform developer (Google), the hardware manufacturer (HTC) and the service provider (T-Mobile) delivered a phone without thinking about how it might accommodate future updates released within the next year or two.

Apple was criticized for not supporting video capture on earlier models in the iPhone 3.0 update, despite those phones actually lacking the processing power to deliver quality recording. Will Android users make excuses for Google once they find that they can't even install the latest software at all?

If this sounds familiar, it should be. These kind of issues were pandemic on Windows Mobile, where the part of Google was played by Microsoft. WiMo 5 introduced an entirely new memory design that instantly made nearly all previous phones ineligible for upgrade. WiMo 6, 6.1 and 6.5 have similarly introduced hardware/software integration obstacles that either complicated or completely blocked users from installing the latest version of their platform's software.

Today's Android phones are typically the same devices running a free alternative operating system by a vendor that exercises even less control over the platform; the Motorola Droid, HTC models, and Sony Ericsson's Xperia were all originally developed as Windows Mobile phones.

Google's Android software platform is more modern and capable than Windows Mobile (which was originally developed to run simpler PDAs), but the core problems facing Windows Mobile aren't particularly due to technology limitations; they're linked to its fractionalized, poorly integrated hardware and software model, where apps aren't guaranteed to look good or perform well and different form factors, hardware specifications, and OS versions introduce complications that are simply difficult to manage. Android's better operating system technology at less cost and with greater licensing freedom does nothing to solve these these core problems.

Platform advancement: iPhone

In addition to the problems of users just obtaining the latest updates, Android also lacks Apple's integrated business model which provides a strong motivation for delivering compelling new features. Apple's regular major updates are designed to sell hardware and keep user satisfaction high. Apple makes enough money from hardware sales to reinvest considerable efforts to keep its software platform fresh and innovative, just as it did with the iPod.

Progressive software updates were so core to Apple's business model that it changed how it accounted for iPhones in order to ensure that its planned software updates would be quickly adopted by users without any cost barriers. The result has been a rapidly advancing platform that introduces novel features and quickly matches new advances appearing on other platforms.

Even in areas where Apple has chosen not to support a particular technology, such as third party background apps or Adobe Flash Player, it has introduced alternatives that blunt the impact of those missing features, such as its centralized Push Notification Server or support for H.264 YouTube streaming.

Again, Apple's centralized control over the iPhone platform allows it to introduce new features that work across all iPhone models and then push these out to all users quickly, ensuring that new operating system features are broadly available to developers. That results in a cohesive, advancing platform that can quickly shed legacy issues while rapidly deploying new system-wide functionality.

Platform advancement: Android

Android lacks the same financial motivation. Google only wants to give phone makers and providers enough code to allow them to deliver their own customized, distinguished products so that it can continue its core business of selling ads and paid search to mobile users. Those partners actually want to have control over differentiated, compelling features that they can use to sell their Android phones in competition with other Android makers.

So rather than Android being a platform being pushed forward by Google, it will largely be advanced by Motorola, HTC, Sony Ericsson, and other makers who all have a history of making dozens of phones with terrible user interfaces and bizarre bundled apps and hardware features that are poorly implemented.

The commonality between these devices will be that they all run Dalvik bytecode and have an open source kernel, something that few Android users will care anything about. Essentially, Android isn't Google's phone platform, it's an open alternative for failing hardware makers to use in place of Symbian, Windows Mobile, and Linux to create the same type of convoluted, fractionalized, and poorly integrated products they're already making. This is also why Symbian, Windows Mobile, Motorola, and Sony Ericsson are all failing commercially.

Google's primary and most significant contribution won't be any major innovation in the core Android platform but rather in its own bundled apps, where Google plans to earn its revenues from via, to put it bluntly, adware and spyware. It should not be a surprise to see that Google is motivated to do things that advance the company's profitability rather than create free value for other companies at monumental expense to itself.

Google has no interest in making Android phones work well with a media app like iTunes because it doesn't have one; it has no motive to develop hardware integration with home theater or WiFi products because it doesn't sell them; it has no need to line up major software vendors or games developers for Android because it doesn't make any money selling hardware, and there's really very little money involved in creating and maintaining a third party software store.

This all happened before

This was the same issue with Microsoft's PlaysForSure strategy, which similarly hoped third party MP3 hardware makers and music store vendors would contribute major efforts to create an ecosystem around it so that Microsoft could then tax the platform as its core software vendor.

The problem was that there wasn't much money involved in running music stores and the margins on hardware were impacted by Microsoft's licensing fees. The only difference in Google's case is that the company isn't planning to levy a software tax for the platform itself, and instead will only try to make money from ads and paid search. But those sources provide even less revenue that can be used to advance the platform.

In effect, with the iPhone Apple acts like a club promotor funding a party for which it collects a cover charge from people who want to attend; Google has invited companies to pay for various elements of the party, each collect their own cover charges, and manage all the promotional elements among themselves even as they each compete for credit and customers and revenues. That's not going to result in a very well orchestrated nor popular party. Additionally, because Google also wants its same apps on the iPhone, there won't really be anything unique about the Android experience compared to the iPhone.

Bundled Apps: iPhone

Apple shipped the original iPhone with a series of bundled apps and no provision for third party software. Apple's own apps set a high standard for iPhone software, astronomically higher than anything that had ever existed in the mobile space before.

Rather than trying to be a small desktop computer (like previous attempts by Microsoft in its Handheld PC, Pocket PC, Windows Mobile, and UltraMobile PC offerings), the original iPhone presented a series of functional but simple apps for primarily viewing local and Internet data, including a new gold standard for the mobile web browser, a central Maps app based on the Google Maps service, a universal YouTube player, a universal QuickTime player, Office and PDF viewers, a rich email client, and the typical organizer apps: Contacts, Calendar and widgets like Calculator, Stocks, and Weather.

Apple enhanced and expanded its bundled apps over the first year, incorporating support for Skyhook Wireless' WiFi geolocation in Maps and direct media downloads from the iTunes Store. With iPhone 2.0, Apple added official support for third party apps; it has continued to bundle its own new first party apps in releases since, including push features for Exchange ActiveSync and MobileMe, the addition of Nike+, Google Street Views, and iTunes features such as Genius playlists.

iPhone 3.0 introduced new bundled apps including Compass, Spotlight search, Voice Memo and Voice Control and broadly upgraded all the existing apps with multimedia copy/paste, video recording, and accessibility features. Bundled apps are updated in the same software updates as OS releases, because they all come from Apple. There's no interference or delay from the service provider, and of course, there's also no variety in hardware makers to manage.

In most cases, Apple has advanced bundled app features ahead of Android, simply because the company started more than a year earlier. However, Google has also demonstrated unique new Android features in advance of Apple. Last year, it showed off compass-activated Street Views on the T-Mobile G1, a feature that was rolled into the iPhone 3GS.

This year, Google debuted Maps Navigation, a turn by turn directions enhancement to the company's Maps. This feature will be even easier for Apple to adopt on the iPhone, as it does not require hardware upgrades. Because Google is advancing its new features to sell search rather than its own phones, there is no reason for the company to deliver unique features exclusive to Android phones, and it has shown no desire to do so.

On the other hand. Google has tried to release features that aren't supported on the iPhone, such as a native Latitude app that allows users to constantly report their location to Google. Apple doesn't currently allow third party developers to install listening or reporting software in the background. Apple also blocked Google Voice, an app that takes over the iPhone interface to supply an alternative, ad-supported phone service that competes with the iPhone's subsidizing mobile partners.

This indicates that Android users will have unique feature access to certain types of apps that Apple blocks third parties from delivering, even in cases where Google would like to make them available to iPhone users. The next segment on third party apps will look at this issue in greater detail.

Apple also offers additional apps that are available alongside third party apps in the App Store, including the free Remote and iDisk, and the $5 Texas Hold'em game. All of Apple's bundled apps are closed and proprietary. All bundled iPhone apps also run on the iPod touch, unless they require some hardware feature unique to the iPhone. Service providers are also capable of offering their own third party apps via the App Store, but can't push software directly to their subscribers.

Bundled Apps: Google

Google similarly delivers a series of closed, proprietary apps for Android. These are an optional install for hardware vendors and service providers, so these may or may not appear on Android devices. If they do, they can't be modified under the terms of Google's license, or distributed without Google's permission for use on unauthorized versions of Android firmware.

Essentially, Google's bundled apps are to Android what Office is to Windows: it may come bundled on a new system, but it's not part of the core platform. When Android is described as "free and open source software," this only pertains to the core OS; much of the value Google offers to Android comes from its bundled apps, which are not free and open source. These bundled apps are referred to as the "Google Experience," and include Google Search, Google Calendar, Google Maps, and its Gmail client. When an Android phone is advertised as "with Google," it means that it is bundling these apps.

Google also develops additional apps that are available alongside third party apps in the Android Market, and often also ports these apps to the iPhone App Store (although Apple has blocked features or complete apps on occasion, from background updates in Google Latitude to the entirety of Google Voice). This means that the majority of the core value that Google delivers for Android is not unique to Android. The only features that are unique to Android and not the iPhone are those few Google apps that Apple does not approve for the iPhone.

In addition to Google's "experience" apps that are optionally bundled with Android, hardware makers and mobile operators may also install their own closed, proprietary apps (or may include FOSS apps of their own or from other sources). These can be used to replace or augment Google's experience apps, creating flavors of Android phones that have next to nothing in common apart from their underlying platform.

If Google's apps are Androids's "Office suite," this mobile provider or hardware maker software is the platform's "preinstalled junkware," although Android phones have yet to establish their reputation for being loaded up with bloated adware, trialware, spyware and other efforts by various parties to cash in on having some control over the user's experience.

The last decade of Windows PC makers' experiences in trying to differentiate themselves before the sale and then to cash in on having claimed the eyeballs of their customers after the sale should provide plenty of evidence that Android hardware vendors will do the same kinds of things. The only difference is that Microsoft attempted to strictly limit what OEMs added to their own Windows PCs; Google is wide open to finding out how far its partners will go to load up their smartphones with advertising revenue potential.

Third party software solutions

These out of the box issues related to the business models of Apple and Google are already evident. The iPhone ships with a full complement of bundled apps that are optimized for the device, and along with the iPod touch, all devices from Apple ship with the latest version of all bundled apps and core software and can update to new versions as they become available.

Android phones such as Verizon's Droid by Motorola ship with apps that don't consistently take advantage of core operating system features (such as multitouch gestures), and don't look right on the device's unusually high resolution screen because they were designed to run on Android phones with a different display.

Droid's camera has impressive software and hardware feature specifications, but it doesn't take good pictures because the hardware and software weren't optimized to work well together. Verizon's Droid Eris, which is made by HTC, ships with an entirely different platform version: Android 1.5, with different features and fewer bundled apps. It's not clear how, when, or even if older or cheaper phones will be able to be updated to the newest Android releases.

Beyond these integration issues related to the differing business models and development motivations of Apple and Google, the two platforms also have an array of third party titles available through their mobile software markets. In both cases, the expandability and forward utility of iPhone and Android phones will be impacted by how rich and diverse and interesting their third party offerings are. The next segment will take a look at how the two mobile platform's software markets compare.

Prince McLean

Prince McLean

-m.jpg)

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

56 Comments

Now that's an understatment if ever there was one.

Check this out- Apple's latest victim:

http://earthlink.com.com/8301-13506_...part=earthlink

Does Google have a censor board as well?

Check this out- Apple's latest victim:

http://earthlink.com.com/8301-13506_...part=earthlink

What is Voice Control?

Something that a lot of us would like to use on you.

Something that a lot of us would like to use on you.

Touche

Now that's an understatment if ever there was one.

Check this out- Apple's latest victim:

http://earthlink.com.com/8301-13506_...part=earthlink

Does Google have a censor board as well?

yes, Google has removed apps from the android store

Perhaps you meant "endemic to" instead of "pandemic on"? Although, overall this series is better written than most AI stuff.