Apple has singled out Greater China— including mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan— as a primary growth center. AppleInsider took a trip to learn more, starting with a week exploring Taiwan followed by a week in Hong Kong and a week in Guangdong Province in the People's Republic of China.

Shenzhen, SEZ of China

Shenzhen is a rapidly growing city on the southern edge of mainland China's Guangdong province (formerly known in the West as Canton). The Shenzhen River separates the city from the peninsula and series of islands that make up Hong Kong to the south. Shenzhen is home to at least 12 million people— unofficially closer to 20 million people.

However, unlike the centuries-old cities of Hong Kong to the south or Canton (Guangzhou) to the north, the area that is now Shenzhen was a sleepy fishing village until 1979, when China radically reversed course by abandoning the failed Cultural Revolution of Chairman Mao Zedong to instead cautiously explore new experiments in market-based economics under the leadership of the more moderate Deng Xiaoping (pictured below in a billboard at Shenzhen's Futian financial district).

Shenzhen was defined as one of a select few "Special Economic Zones" that would be opened up to foreign investment, allowing both international and local companies to trade and invest without the same level of oversight and regulation of the Communist Party's centralized control over trade policy, taxation, land use and business approvals. Corporate income taxes within the SEZ are reportedly set at 15 percent, lower than Hong Kong's 17 percent and less than half of the 33 percent typically applied to companies across the rest of China.

In comparison, corporate tax in the U.S. is nominally 34-35 percent but most large corporations pay an average effective tax rate of 12.5 percent, varying on their level of loophole exploiting shenanigans. Apple reports that its effective U.S. tax rate is just above 26 percent. Google recently reported an effective tax rate of 15.7 percent, Microsoft reported "approximately" 19 percent and Samsung (in South Korea) reportedly pays corporate taxes in the low teens (12-16 percent).

Decades of Mao's massively destructive ideological efforts to rid the entire nation of any hint of capitalism and even the nation's traditional culture— Mao even killed Lunar New Year celebrations. Imagine LBJ canceling Christmas— while also dictating every aspect of the economy based on folksy hunches, diametrically opposed to any feedback or expert input.

China's post-Mao shift toward the adoption of more pragmatic, open economic policies rapidly turned a village into the massive city of Shenzhen, a vibrant economy funded by billions of dollars in foreign investment. As one of the world's fastest growing cities, Shenzhen is not just big but modern.

The entire area was plotted out and built within the last few decades, with large parks and "green belts" of urban trees, dense commercial districts and a web of underground metros stitching the city's districts together. It was designed for growth. The city was laid out with massive avenues accommodating not just many lanes of vehicle traffic, but also dedicated bus lanes and bike paths, as well as enormous pedestrian tunnels and broad overpasses to bridge the rivers of traffic.

"China's Silicon Valley" growth vs actual Silicon Valley: in metros

The scale and speed of Shenzhen's unfathomable growth is illustrated in the construction of its metro system, which didn't even get started until 1999. The first segments only opened ten years ago, but today it has more than 130 stations on over 100 miles of tracks. Original plans to nearly double that by 2020 were recently accelerated in order to begin new service in 2016. And by 2030, there are plans in motion to have 447 miles of metro and commuter rail track connecting the city, with direct links to not only the metro system of Hong Kong to the south, but also to the metro system of Dongguan to the north.

Because they are all brand new, the metro stations are pristinely clean and modern, with elevator-like gates that prevent anyone from entering the tracks or jumping in front of a train. Every metro station in Shenzhen had functioning bathrooms (almost as shocking as how easy it was to find a trash can or recycling bin; they're everywhere). Many stations also had x-ray machines for scanning riders' backpacks and luggage as a security measure to handle the incredible numbers of people using the system. They were so efficiently run that it was barely even an inconvenience.

By way of comparison, San Francisco (which proudly calls itself "Transit First") began construction of its 1.7 mile Central Subway project five years ago, aimed at adding just 4 new stations. There is still no plan for when the subway might actually reach the end of its initial tunnel segment in North Beach, let alone any future expansion, but the project hopes to begin initial service to Chinatown by 2019. The project has so far budgeted over $1.5 billion, making it one of the most expensive subways projects in the world, despite being value engineered into a limited capacity line that can't handle more than two short cars per train.

San Francisco's existing 5.5 miles underground Muni metro (connected to 66 miles of street rails) haven't previously been expanded since the 1980 opening of the Market Street Subway tunnel (which Muni shares with regional BART). San Francisco's metro is also unreliable, insanely overcrowded, falling apart, regularly delayed by jumpers or tunnel trespassing, and has shut down all public bathrooms in stations, resulting in many of its escalators failing to work because they are clogged with human excrement.

By the time America spends about $1 billion per mile to build a perfunctory subway segment in San Francisco by 2020, China will have spent just $130 million per mile (around $13 billion) to complete another 100 miles of new metros in Shenzhen, serving 102 new stations on four additional lines. That's an expansion similar in total track length of the entire regional BART system, but with 2.5 times as many stations. Meanwhile, Silicon Valley will just be starting its construction to extend BART 5 miles into San Jose, at a cost of at least $4.7 billion (again, about $1 billion per mile).

That means growth and commercial activity in Shenzhen will continue to move as fast as people can walk, while one of the most innovative, affluent and commercially successful regions in America will have most of its labor force (along with its executives) still wasting multiple hours every day unproductively sitting in traffic on congested freeways that have no room for expansion, while the crumbling transit alternatives incur delays and breakdowns related to their advancing age and obsolete train control system technology.

Apple's manufacturing in Shenzhen

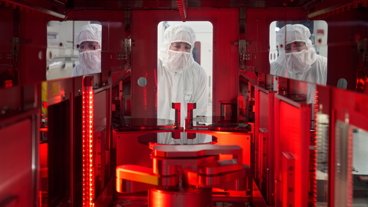

The influx of foreign capital into Shenzhen, combined with a vast supply of labor and the infrastructure support of the Chinese government— along with the city's proximity to Hong Kong for global shipping— rapidly built Shenzhen into a manufacturing center. By 2001, Apple had few competitive options for building its notebooks and iPods other than Taiwan's Hon Hai, which since 1988 had been operating in the Shenzhen SEZ as Foxconn.

Intel similarly contracted its motherboard business to Foxconn in 2001 in order to focus on its domestic production of silicon chips. Other Western firms including BlackBerry, Cisco, HP, Dell, Motorola, Nokia, and even Japan's Sony, Nintendo and Toshiba and Taiwan's Acer were all contracting their manufacturing work out to Foxconn because not only was it inexpensive to build in Shenzhen, but the economies of scale in manufacturing there were driving technical, operational and sociological capabilities that few other places in the world could match.

When U.S. President Obama asked Steve Jobs in 2011 how America could win back mass production manufacturing jobs from China, Jobs reportedly countered, flatly, "Those jobs aren't coming back."

Obama invites tech leaders to dinner, 2011The issue wasn't cheap labor, but rather that three decades of large scale investment in building entire supply chains to support large scale manufacturing in China were not something that the U.S. could simply flip a switch to copy, any more than America can suddenly match the construction of the roads, metros, high speed rail and vast stretches of commercial towers that China has been building while the U.S. deferred maintenance on its existing infrastructure and canceled public transit projects over political ideology.

In 2013, Google's Motorola subsidiary announced ambitious plans to assemble Moto X smartphones in the U.S., but even with a limited production targets and all the power of Google's capital, the initiative failed miserably, losing billions of dollars and, somewhat ironically, resulting in the sale of Motorola to a Chinese company.

Apple has recently emphasized the component manufacturing it sources within the U.S., including display covers built by Corning in Kentucky and processors manufactured in Austin, Texas, along with a variety of other domestic suppliers. Apple has also used domestic factories to build limited production numbers of its new Mac Pro towers and continues to assemble build-to-order Macs in California. It also funded an ambitious sapphire plant in Arizona that failed, which has since been retargeted for use as a data center.

However, the very large scale manufacturing of tens millions of iPhones and iPads remains impossible to move to the U.S. both because the country lacks available skilled assembly labor and the industrial engineers to orchestrate them, and because there's simply no infrastructure supporting vast supply chains of both basic and specialized parts, and the tooling experts required to assemble them in massive, automated production facilities.

Westling with China: Apple's WAPI War

Manufacturing in products in China was far easier than selling goods there. While Apple began building iPhone in 2007, it negotiated on and off with the state run carriers, including China Mobile, for years without reaching any partnership agreement because the carriers refused to agree to revenue sharing and demanded control over apps, among other issues. Apple's first store in China opened in Beijing in the summer of 2008 without the iPhone.

That November, the smaller state-owned carrier China Unicom agreed to begin carrying a specialized version of iPhone 3G and 3GS, albeit with support for WiFi removed. Since 2004, China had banned standard 802.11 WiFi, ostensibly over security concerns, as it launched its own "WAPI" wireless standard that it hoped would give it domestic control over emerging markets without having to pay royalties to Western patent holders for their intellectual property (much like Google's VP8, WebP and Android). Rather than supporting WAPI to appease the state, Apple produced "official" iPhones for China Unicom without WiFi or WAPI

Implementing WAPI-style wireless networking on products sold in China requires a joint partnership with one of a select few domestic manufacturers; Western companies were not allowed to see the details of the wireless specification. That made WAPI a mandated technology perfect for opening access to state surveillance, as well as an effective restraint on trade that forced outsiders to manufacture in China while blocking imports, splintering global economies of scale and offering a substantial advantage to members of China's emerging domestic tech industry.

Rather than supporting WAPI to appease the state, Apple produced "official" iPhones for China Unicom without WiFi or WAPI. In the short term, it appeared to be a failure. Those models didn't sell very well; imagine being stuck on a 2008-era, slow AT&T-like GSM network with no ability to use WiFi as a backup.

However, the demand for iPhones among affluent Chinese residents simply induced grey market imports through Hong Kong, which not only brought in a flurry of standard iPhones that supported WiFi but also skirted state sales taxes. This, along with the ISO's refusal to approve WAPI as a standard in parallel with WiFi, helped convince China to abandon its WAPI-only policies, just in time for launch of iPad.

That spring Apple gained the certification to sell a special iPhone 3GS model supporting both WiFi and WAPI, a move that rapidly increased Apple's revenues in China by shifting official, domestic iPhone sales from a few thousand to more than 2 million units per year.

After 4 years of making iPhones, China gets 11 stores to launch iPhone 5

In July 2010, Apple opened a second store in China: its Pudong Shanghai flagship featuring a distinctive glass cylinder entry. In September, Apple launched iPad, also with support for standard WiFi, along with two additional stores in Shanghai and Beijing.

A year later in September 2011, Apple opened another store in Shanghai and its first store in Hong Kong, at ifc mall (pictured below). The new Hong Kong location was the company's first official storefront within about 1,000 miles (1,500 km) of its primary production site for Phone and iPad in Shenzhen.

ifc mall Apple Store, Hong KongIn early 2012, Apple's three year exclusive deal with China Unicom expired, enabling it add China Telecom. Like Verizon Wireless in the U.S., China Telecom used a CDMA network. Apple had launched a CDMA iPhone 4 with Verizon one year earlier in early 2011, and then launched iPhone 4S in October 2011 on both Verizon and Sprint. The first Retina Display iPhone to sell in China arrived in early 2012 in the form of a specialized iPhone 4S with support for WiFi and WAPI, providing both GSM support for China Unicom and CDMA for China Telecom.

That winter, Apple opened a blitz of stores in Greater China, starting with Festival Walk in Hong Kong, another store in Beijing, its first store in Shenzhen just across the border (detailed later in this article), its first in the middle of the country in in Chengdu, and finally its third store in Hong Kong at Causeway Bay (below). All of the stores were opened in time for 2013's Lunar New Year, assisting a strong launch for the first Retina Display iPhone to be officially sold in mainland China.

The opening of five new major flagship stores— including two entirely new cities in China— in such a short period of time was particularly noteworthy because Apple had also just fired its retail chief John Browett after only seven months on the job. Prior to Browett, Apple Retail had been running itself without a designated executive for a year following the departure of Ron Johnson.

China and LTE necessitate a dozen model variants for iPhone 5c & 5s

The "world band" UMTS/CDMA 3G support in iPhone 4S only required two models globally (the second one tweaked for China), but 4G LTE support in iPhone 5 required four regional versions, essentially: AT&T (later tweaked to support T-Mobile's launch), Verizon, China, and Elsewhere (the Verizon model with CDMA turned off).

The follow up launch of iPhone 5s not only involved the development of Touch ID and a new 64-bit A7 processor, but also required a new set of model variants to support an expanded number of carriers' LTE bands worldwide. Apple also partnered for the first time with China Mobile, which expanded LTE not just to new bands, but also China's alternative WAPI-like version of patent-skirting LTE known as LTE-FDD, as well as its custom variant of CDMA known as TD-SCDMA, neither of which pays royalties to Qualcomm for using its technology.

In addition to the six flavors of iPhone 5s— basically: AT&T LTE (Verizon model with CDMA turned off); Verizon CDMA/LTE; China Telecom (Verizon CDMA without active LTE), Non-Verizon CDMA/LTE; European GSM/LTE; China Unicom GSM (no official LTE); Asia GSM/LTE; and China Mobile (TD-SCDMA/LTE-TDD)— Apple also relaunched iPhone 5 in the colorful case of the new iPhone 5c, paired with an identical six regional model variants.

Angela Ahrendts returns to opening a flurry of new Apple Retail stores in China

To launch the new iPhone 5c and 5s, Apple opened two new stores in Greater China: its fourth in Shanghai and its fourth in Beijing; both opened in time for the Lunar New Year in 2014. And again, both stores were opened without Apple Retail having any dedicated executive at the helm. That's no doubt why the company's chief executive Tim Cook was so excited to introduce the hiring of Burberry's Angela Ahrendts in late 2013.

Angela Ahrendts poses with Apple fans at the Omotesando, Japan Apple Store's grand opening. | Source: Mac Otakara via Twitter

Angela Ahrendts poses with Apple fans at the Omotesando, Japan Apple Store's grand opening. | Source: Mac Otakara via TwitterAfter taking over Apple Retail the next spring, Ahrendts presided over the opening of two more stores in China last summer: Apple's first in Chongqing, in the middle of the country, and one in Wuxi in the urban periphery of Shanghai. Over the last quarter, Apple opened another six stores in China: its first in east-central Zhengzhou; its first in Hangzhou just south of Shanghai at West Lake (featured at the company's Spring Forward event); its second and third stores in central Chongqing; its first in Tianjin just south of Beijing; and its first in Shenyang, just north of border with North Korea.

That activity resulted in twenty stores being open for the 2015 Lunar New Year at the launch of iPhone 6 and 6 Plus. Incidentally, advances in the Qualcomm MDM9625M Baseband Processor and radio circuits have enabled Apple to reduce the number of global model variants to just four: AT&T, Verizon, International and China Mobile. That reduction of model variants also made room for the same four variants required by iPhone 6 Plus.

Entering the People's Republic of China

Honestly, just a few months prior to visiting China I realized how little I knew about the country. For starters, I didn't even know that half of the land area within the familiar outline of China is nothing. Much of the western side is consumed by the Taklamakan Desert in the northwest and below that, the permafrost of the southwest's Tibetan Plateau, an area larger than Alaska and Texas put together, at an average altitude of nearly 15,000 feet. So there really aren't very many people living west of the middle of China, as can be seen really quickly by looking at a map of where the cities are.

That means while China has nearly the same land area overall as the United States (3.7 million square miles, compared to America's 3.8 million), the vast majority all live in the eastern half. China also has a population 4.25 times greater. If you live in the U.S., you can visualize four times as many people living where you do, then push them all into just one half of your neighborhood.

On top of the raw population figures, you also have to factor in that centrally planned polices have concentrated potential job opportunities in cities, where the infrastructure is. And in the background, you have a history of decades of the Cultural Revolution, an effort by the police state to eradicate original individual thought and even people's traditional culture as part of a massive political experiment.

So while I'd ventured into the Chinatown of a variety of American cities, and had twice been to Taiwan and now to Hong Kong, I was actually pretty terrified of entering Actual China, even before considering that I don't have even a rudimentary, entry level grasp of Chinese language. And I was traveling with an aerial drone. And I didn't have a visa.

While I'd read that obtaining a visa was more difficult for Americans (you're supposed to apply at your home consulate, not in Hong Kong, and I'd heard it could take several days just to obtain a single-entry visa), it turns out that the the frosty reciprocation of visa handicaps and hardships traded between China and the U.S. have eased recently. I was given a 10 year, multiple entry visa overnight (for a fee). All that was left was taking the metro an hour north of Hong Kong to the border, where you walk through the station and into customs.

I breezed through, along with my drone (which is actually built in Shenzhen, come to think of it). I then took the virtually identical Shenzhen metro (also operated by the same MTR that Apple featured as an enthusiastic client of iOS products) to my hotel in the Luohu District along the sprawling Shenzhen Central Park. My next stop, necessitated by technical issues I'll discuss later, was Shenzhen's Apple Store.

Apple Retail in Shenzhen

Fortunately, the only Apple Store within almost a thousand miles (at least within mainland China) was just several stops away on the metro. It's in the Holiday Plaza mall in the Nanshan District, a region that includes High-Tech Industrial Park (which serves as the headquarters for both Apple's Chinese social media partner Tencent and its smartphone competitor ZTE).

I inadvertently took the scenic route from the metro station through the entire downmarket mall (past its ice skating rink and endless small shops) before realizing that the Apple Store was at the more prominent opposite end, opening out into a pleasant plaza area with its own, more direct entrance to the metro.

The store itself is a cavernous single level that opens both into the mall and to an outdoor area with a perfectly centered water feature. Both the store and the plaza were full of people, even though I arrived just a few minutes before the store closed. There were a few people who stuck around afterward to continue using its free WiFi hostspot. I returned later to take more photos of the location (it was even busier then), but my first visit has been dedicated to finding a local SIM card for my phone.

Unlike the Hong Kong Apple Store, which could sell me a very cheap (about $10) SIM nano card providing a week of unlimited data and a local phone number for my iPhone 6, the Apple Store in Shenzhen had to refer me to a local carrier to buy one. When you do buy a SIM card in China, you have to provide your passport, a step that's also required when buying train tickets.

Across the road (and metro station) from Apple's Shenzhen store is "Window of the World," a theme park that includes copies of a variety of landmarks, including the Eiffel Tower. Just down the road is "Splendid China," another tourist attraction that similarly supplies a series of scaled-down copies of famous landmarks within China, such as the Great Wall.

Surprise City

In addition to tacky landmark copycat parks, there's also a variety of actually quite interesting areas in Shenzhen, such as the OTC Loft (below), a block of old factories that were converted into artisan galleries and small restaurants like the handmade noodles place I ate at while watching the noodle making in action. It was excellent, and very inexpensive.

Riding a couple stops past the Apple Store metro station at Window of the World takes you right up to the nearby coastline, where you can see the north edge of Hong Kong across the bay (and the vast Shenzhen Bay Bridge that connects to it). There are massive luxury glass condos here, a vast golf course, and huge tracts of land being prepared for new rows of skyscrapers to the east in the direction of Futian.

Further west (below), there's another expansive strip of Nanshan's very new towers— a city unto itself— with a stadium and lots of other things to do, reaching out toward "Sea World," another local tourist attraction centered around a half-buried cruise liner converted into shops (I didn't explore it, but I did fly over it).

None of this felt like anything I had expected to see in China. It felt like it could be San Diego. The weather felt like it could be, too: Shenzhen is coastal and moderately tropical. It was a comfortably cool 68 degrees, albeit with more humidity than I'm used to (this was in the last week of February). The severe pollution issues that many cities in China are struggling with are less of an issue in Shenzhen, in part because the ocean blows the pollution away (as in San Francisco) rather than sealing it in under an inversion bowl (like Beijing, or Los Angeles).

Part of the reason much of Shenzhen doesn't feel like China is because it's a melting pot of diverse foreigners, particularly obvious in certain expat-dominated neighborhoods and nightlife districts. These aren't particularly American, nor British, nor anything else easily identifiable. I met artists performers from Ukraine, a family from the Netherlands visiting their soccer-teaching son, an English teacher from the UK, and students studying in Shenzhen from a variety of different places. There are also ethnically Chinese people living in Shenzhen from all over the rest of China.

Given that most of Shenzhen itself is barely 30— and an incredible amount of it has been built just since the iPhone debuted in 2007— it's kind of hard to define anyone here as being "local." If anything, the nightlife of Shopping Park (which appeared to be an old mall development converted into a massive string of connected bars and clubs) felt like Berlin: a mix of new and old, internationally cosmopolitan and working-class affordable.

A typical night started at what seemed like a cafe crossed with a convenience store, where you can walk in and pick from a wide selection of single bottles of beers from around the world, then pay a couple dollars for it, open it up and drink it right there in the outdoor patio area. Drinks in the club were less than $5, you can avail yourself of a cooked-to-order, late night BBQ snack-feast right on the street. Things weren't shutting down at 5 AM when I threw myself in a cab (they are extremely cheap, and strictly regulated) for a ride home.

I started having some doubts about the regular reports we've been getting that Shenzhen is a filthy hole where Apple enslaves underage teenagers to build devices that nobody who lives there can afford. Because in realty, virtually everyone riding the subway or relaxing in one of the vast green parks carried a smartphone, and a surprising number of them were holding an iPhone 6. I met iPad assemblers from Foxconn, not outside the gates of Foxconn City as Mike Daisey claimed to, but out in the middle of Shenzhen's sunny green parks, which are a quick metro ride away (a trip that costs less than $1) from those factories.

Of course, I also witnessed a lot of poverty, in the sort of crowded, crumbling high rise tenement projects that existed before technology and foreign investment began gentrifying the region's Mao-ed down collective farming villages into high rise towers and high end malls, middle class theme parks and extensive open green spaces.

I have followup reports on my observations in the People's Republic of China examining its distinct culture, technological surprises, and Apple's current operations and future prospects, within what is already a vast consumer electronics market seriously rivaling that of the U.S. If you have any specific questions, ask in the comments and I'll try to address them in future segments examining Apple in Greater China.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

37 Comments

Top article I feel like I've been there. Ironically I was in the Brisbane CBD Apple store today and while the outside of the building is very elegant the back where the tech area is, was reeking of bacon that seemed to be coming in the rear entrance. I hope they don't plan on selling the edition watch there. It was incongruously nauseating.

Another very good read (although I thought the 3 paragraphs denigrating BART were out-of-place).

Please continue this series of articles about other world regions!

Obama and Tech Leaders and Steve Jobs "in 2012," a year after Steve's Death? I think not!

DED, good article... but you need to correct that quote "When U.S. President Obama asked Steve Jobs in early 2012 how America could win back mass production manufacturing jobs from China" Steve died Oct, 2011 - I know that question you're referring to, I remember it, I think it was either early 2011 or late 2010.. not sure..

A very good piece. You should visit Shanghai next time. Surprised to hear Tim Cook to announce there will only be 40 stores by mid 2016. It should be around 100 stores. Apple is moving too slow in China.