After a surprise debut earlier in March, Apple's open source ResearchKit framework is being hailed by some as the future of distributed medical research. Dr. Stephen Friend, who worked on the project and now serves as a medical technology advisor at Apple, paints a picture of the tool's early days.

In an interview with Fusion, Friend said he first caught wind of what would ultimately become ResearchKit in September 2013, when he gave a talk at Stanford's MedX conference touting the benefits of open source health data.

Friend is well versed in medical research technology, having worked for pharmaceuticals giant Merck before cofounding Seattle-Based nonprofit biomedical organization Sage Bionetworks. He believes that the right mix of cloud computing and open health data collection would put a wealth of information at researchers' fingertips, profoundly affecting the field.

After the presentation, Friend was approached by Michael O'Reilly, another medical expert who was reportedly hired by Apple between late 2013 and early 2014. Prior to Apple, O'Reilly Was chief medical officer and executive vice president of medical affairs at pulse oximeter firm Masimo Corporation prior to Apple

After Friend's talk, O'Reilly approached the doctor, and, in typical tight-lipped Apple fashion, said: "I can't tell you where I work, and I can't tell you what I do, but I need to talk to you," Friend recalls. Friend was intrigued, and agreed to meet for coffee.

Friend declined to comment on whether his idea of collecting volunteer health data on a massive scale was the basis of ResearchKit, or if Apple had already formulated a similar plan before he joined the initiative. He did admit to making frequent trips to Cupertino and other cities to work on the ambitious program.

As for why Friend chose to help Apple's cause instead of competitors, he said it came down to patient privacy. Other tech companies "make their power by selling data...They get people information about other people," Friend said. "Apple has said, 'We will not look at this data.' Could you imagine Google saying that?"

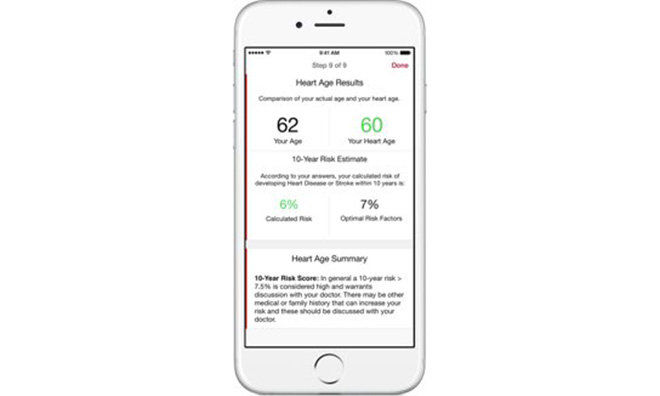

So far, ResearchKit has seen a good bit of success. For example, a joint Stanford University and University of Oxford cardiovascular study attracted more than 10,000 participants in about one day, a feat that would have taken 50 medical centers an entire year to reproduce.

Euan Ashley, a Stanford researcher who helped create the myHeart app that goes along with the study, told Fusion that he has been working with Apple on the project for more than a year.

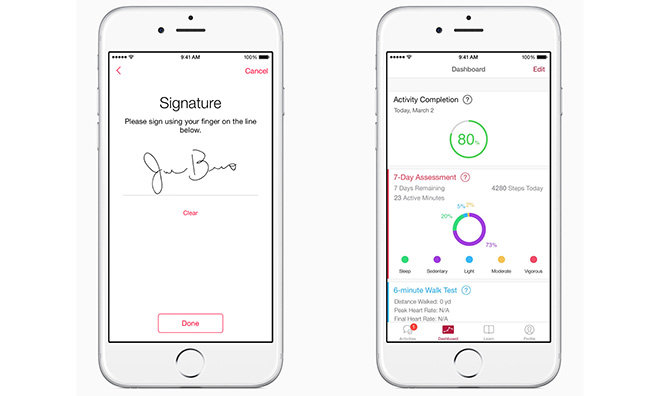

Alongside the heart study, there are currently four other active programs with apps in the iOS App Store, including an asthma self-management program from Mount Sinai, Weill Cornell Medical College, and LifeMap; a Parkinson's study from the University of Rochester and Friend's Sage Bionetworks; a diabetes analysis tool from Massachusetts General Hospital; and a breast cancer study from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Penn Medicine, and Sage Bionetworks.

In creating the ResearchKit framework, Apple has acted as a facilitator, leaving app development up to each research team, Ashley said.

The viability of data coming from ResearchKit has yet to be vetted, but some industry insiders feel Apple's platform is a model against which future mass-distributed open source medical research will be measured.

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

13 Comments

I thought 2014's ?Pay would be hard to top as the single most important service Apple brought to customers, but 2015's ResearchKit could very well trump that if it leads to healthier lives.

Research Kit is fucking huge, and it's clear that most people don't realize or understand the depth of it's potential. As time goes on, and it integrates more fully with Apple Watch, which will get even more health sensors, it will become even more useful and profound.

I would love to read an article about how a person interacts with a research app... both as a health data reporter, and then as a receiver of the data.

What are the implications of it being open source? - Ability for non-Apple employees to extend the APIs? - Ability to use it on non-Apple platforms? - others...?

Apple hirining people with rhyming medical researchers. The way of the future.