If you listen to groupthink critics on Apple, you'll hear that the company is deeply troubled by too much reliance on iPhone sales, aging Mac Pro and Mini offerings that haven't been updated in years and a stagnating market for iPads that has fallen precipitously since Peak iPad occured in 2014. They're wrong, here's why.

A visit from an insane time traveler

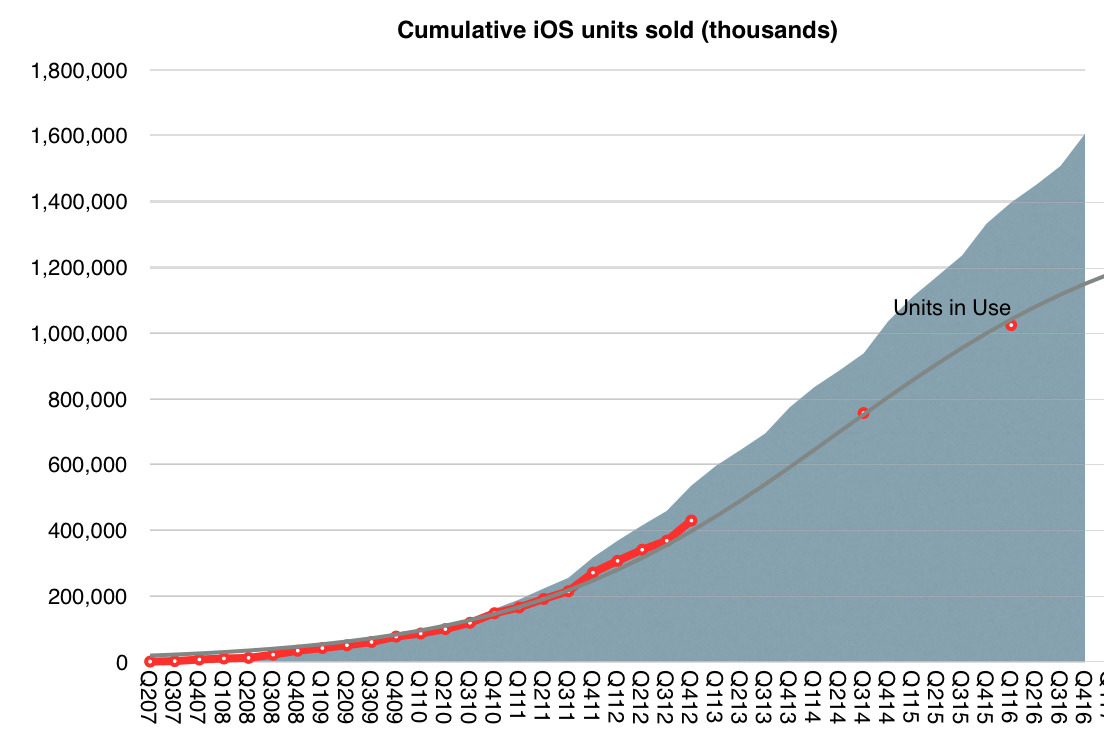

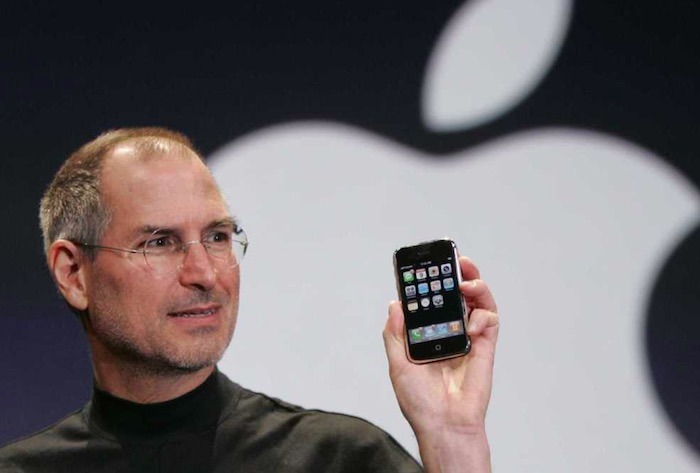

Imagine it's 2007 and you've just witnessed Steve Jobs introduce the new iPhone. Suddenly a time machine appears and a person from ten years into the future jumps out. Naturally, you ask whether Jobs' intended goal to reach 1 percent of the global smartphone market ever materializes.

"Never mind!' the person from the future says. Instead he gravely warns you that, "in ten years, iPhone will account for about 60 percent of Apple's revenues! Apple will be incredibly reliant upon iPhone profits!"

"Holy cow," you reply. "iPhone will be contributing sixty percent of Apple's $19.32 billion dollars in annual revenues in a decade? That means iPhone will grow into an $11.6 billion business!"

"No dummy, in ten years Apple's annual revenues won't still be today's $19.32 billion, it'll be $215.64 billion. But that's the problem: most of that growth will come from expanding iPhone sales. Conventional Mac computer sales will only grow from today's 5.3 million per year— $7.4 billion worth— to 18.5 million Mac ten years from now, $22.8 billion worth of Macs. Apple will be bringing in $136.7 billion in revenues from iPhone! It will be so terrible. Warn your friends!"

"That's bad?" You ask. "So in ten years, Apple will be bringing in far more revenues from phone sales than anyone else ever has, while also tripling its current sales to reach $22.8 billion worth of computers ten years from now?"

"No dummy," the time traveler says. "Apple will sell $22.8 billion worth of Macs. It will also invent a new lightweight tablet computer called iPad, and in fiscal 2016 it will sell $20.6 billion dollars worth of those. So in total, $43.4 billion worth of general purpose computing devices a decade from now, plus $136.7 billion worth of phones."

"Well it sounds like Apple does pretty well with both computers and phones," you say.

"Hardly!" The time traveler snaps. "Ten years from now, nobody is buying Xserves, nobody buys the cheap Mac mini, and desktop 'Pro' Macs virtually disappear from the radar. Demand for desktops is so light that by 2017 Apple hasn't significantly updated its slowest selling desktop Macs for years.

"Instead, it will ship a premium-priced MacBook Pro that's super light and thin, featuring a Touch Bar that replaces the top row of function keys with a dynamic touch screen that suggests things you might want to type next! It's terrible, people want to see an updated Mac Pro they're not going to actually buy, not another update of a product that will actually sell by the millions."

"It sounds like you are totally deranged," you observe.

"You just don't get it!' he screams. "Apple might be making money and developing products people will actually buy, but the reality is that— in unit sales— Apple sold more iPads in 2014 than in 2017. It turns out that Apple could make more money selling people big iPhones than from small iPads. Once the big screen iPhone goes on sale, the numbers of iPads sold also goes downward, dangerously inflating the numbers of iPhones sold. It's like Apple doesn't even care about unit sales and its only focused on building products that make money!"

"What's Apple's future stock price?" you ask as you look up the company's current valuation in the Wall Street Journal, because you don't have an iPhone yet and the phone you have lacks WiFi or a data plan because they are all just too expensive in 2007.

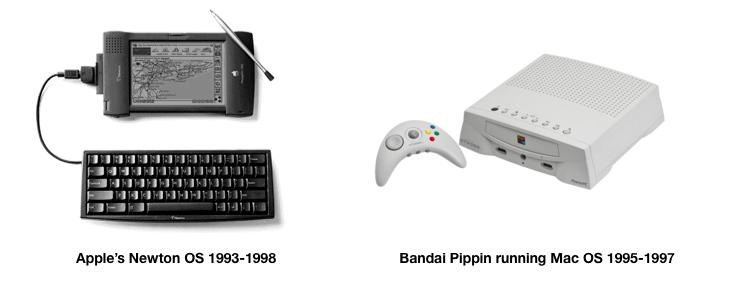

"Sorry, I have no time left," the time travel says. "I have to go back in time even further to warn people in 1997 that Apple is getting rid of QuickDraw 3D and that Pippin and Newton PDA sales are going to go away completely, replaced by a new ARM-powered computer that does little more than play music from a hard drive. Can't wait to see the terror on their faces! Plus I need to buy some more Apple shares to finance this time machine. It's expensive to maintain!"

This time traveler story is not actually true. However, the insanity he spews is exactly what the tech media is reporting today. From bloggers at The Verge to The New York Times to clickbait generators at Forbes, Business Insider and other surveillance-ad content mills to even analysts seeking to say something of merit about the company that will make them look smart, virtually everyone in tech is merely saturating the web with stale, vapidly ignorant observations about Apple that are purely ridiculous. The best question, however, is: why?

Balloon logic

The tired tropes of Apple's "troubling" situation are a form of balloon logic; ideas that seem substantial until you scratch the surface and realize that there's nothing really there but a thin bit of rubbery garbage stretched out around captive air.

Apple does face some significant challenges ahead in its efforts to maintain and expand its position and profitability in personal computing. However, the general consensus among Apple's critics fails to maintain a firm grasp on what these actually are.

There's a simple explanation for why analysts, pundits and journalists regularly doubt the capacity of Apple— the most consistently, commercially successful tech company ever— while exercising a doe-eyed credulity in the promises of every potential new competitor that announces itself. Analysts, pundits and journalists needn't be consciously biased against Apple to repeat fiction about the company; they only need to be selectively informed by Apple's rivals and lack any capacity for critical thinking or any valid insight into the market.

Analysts, pundits and journalists needn't be consciously biased against Apple to repeat fiction about the company; they only need to be selectively informed by Apple's rivals and lack any capacity for critical thinking or any valid insight into the market.

Apple loves the darkness

It's not just Apple's competitors that are contributing toward the murky, delusional picture of Apple's current status. Apple itself benefits from secrecy and a public kept ignorant to its intentions and strategies by a lazy media.

It's much easier to surprise and delight audiences with products they don't see coming. That's why Apple didn't outline in advance the various features of its 2016 product introductions until they were nearly ready to sell, and doesn't print out a detailed technology roadmap of where it's headed.

Nobody was detailed well in advance on Apple's Continuity strategy for linking Macs and iOS devices using Bluetooth and WiFi, and few even comprehended the significance of this when it was unveiled. Even fewer— not even yours truly— foresaw that Continuity would also expand as a platform glue to deeply integrate Apple Watch features, or to associate new wearables like AirPods into Apple's magically hyper-connected ecosystem of devices.

By not outlining what it was doing and why, Apple gained a huge competitive advantage that it could incrementally roll out without its competition copying its moves.

Microsoft apparently thought it was matching Apple by rolling out Continuum, a way to turn a smartphone (something Microsoft is struggling to sell) into a desktop PC (something few people need anymore). Google introduced its own concept for merging Android (its mobile platform of low quality app titles) to run on ChromeOS (its unpopular Linux netbook that it struggles to give away).

The media praises both of the latter with standing ovations while failing to even grasp that Apple's Continuity is the only one of the three that offers the ability to sell new hardware by facilitating new capabilities that people will actually want, rather than just promising to do something that pundits rooted in the past can nod their heads along with, but which makes very little actual commercial sense.

Writing for The Verge nearly two years ago, Tom Warren crowed of Continuum: "Microsoft turning phones into PCs feels like the future!" Right, nothing says "future" like Windows Mobile phones and desktop PCs.

Before realistically examining Apple's current position in personal computing— a market that involves Macs and iOS devices including iPhone and iPads— consider how consistently backward and incorrect the general perception of Apple has been across the last several years, and— most importantly— why people were wrong.

Statistical fallacy has resulted in foolish advice and incorrect predictions

It's not difficult to create persuasive arguments by massaging figures in the model of IDC, Gartner and Strategy Analytics, or to artfully chart out data points in the manner of say, Business Insider. However, no matter how plausible a story might seem, or how incontrovertible a series of data points appear to be, if they predict an outcome that doesn't actually occur, it's pretty clear that something was wrong in that logic. Even a minor change in one variable can frequently result in a totally different competitive environment

Mainstream technology reporting— and even many tech-specific blogs— have been incredibly bad at predicting trends in the industry. So bad, in fact, that almost everything they predicted is, in retrospect, laughable.

One of the core problems in predicting the future path of technology is that even a minor change in one variable can frequently result in a totally different competitive environment going forward. This results in not just the wrong answers to given question, but in asking the wrong questions entirely.

@BenedictEvans on 1964's idea of what the future would bring. https://t.co/JqOlUN6LfG

— Jack Shafer (@jackshafer) January 15, 2017

Another factor that many future predictions often fail to account for in their logic models is that while history might repeat at times, everything that happens invites a competitive response by those witnessing the events. For example, when Apple introduced the Macintosh in 1984, it triggered a series of competitive responses, most notably (in retrospect) from Microsoft Windows. When Apple introduced iPhone, something similar happened. History repeats, but intelligent systems learn and adapt in tandem

However, Apple's executive team itself responded differently because it was informed by the past.

Much of the tech media identified one pattern (thinking that Apple's product would again be threatened by a commodity platform) but completely failed to anticipate how Apple might respond differently to this threat after having narrowly survived the previous one. History repeats, but intelligent systems learn and adapt in tandem. Evolution demonstrates how one small change can have a huge impact on competition going forward.

2007: Apple figures out smartphones and "walks right in"

With Apple's iPhone recently reaching a ten year milestone since its introduction, it's particularly easy to review what people said about that product and contrast this with the known history of iPhone.

Initially, many perceptions of Apple's potential (or lack thereof) in smartphones largely aligned with the iconically misguided comment made in late 2006 by Palm's chief executive Ed Colligan: "PC guys are not going to just figure this out. They're not going to just walk in [and take over the smartphone industry]."

Colligan wasn't an idiot. He'd run Palm quite successfully from its early PDA days into the blossoming of PalmOS smartphones. Palm had also worked closely with Microsoft and with the "PC guys" of the day (notably Sony) to license technology in both directions (from Microsoft, and to Sony) and to partner in building the emerging notions of what a mobile computing platform should be.

However, Colligan ended up being very wrong about Apple, which very much did "figure out and walk in," not just with smartphones but also in tablets with iPad. Conversely, Colligan was eventually right in the sense that "PC guys" wouldn't be able to "walk in" ...on Apple.

With iOS and the App Store, Apple changed the rules so drastically that Microsoft, PC makers and even Palm itself couldn't "figure out" how to reenter the smartphone market— now redefined by iPhone and iOS.

2009: Palm itself fails to "walk right in"

Palm's response to iOS, named webOS, was introduced just a couple years later but failed to launch its own iPhone-like success with Palm's Pre phone hardware. The webOS team also couldn't find traction for its iPad-like TouchPad tablets. Not even the world's largest collection of "PC guys" at HP could figure out how to put things back together again after acquiring Palm in 2010.

The failure of Palm and webOS wasn't a simple matter of Apple's people being inherently genius and non-Apple companies being full of idiots. Palm's webOS team had actually recruited away tons of talent from Apple's iPhone team, and its development was lead by Jon Rubinstein, who served as Apple's Senior Vice President of Engineering across the decade that introduced iPod and turned Mac sales around. It would be an incredible understatement to say that Rubinstein had deep insight into what had worked at Apple, and he shared a particularly close working relationship to Steve Jobs.

Despite all that, Palm's webOS earned little more than exuberant praise from the media. The ambitious project failed to return Palm to greatness, and ended up doing nothing for HP (or LG, which later acquired it). Apple talent, Apple insight and Apple executives weren't enough to cultivate an independent Apple-like success at Palm, and weren't even enough after being combined with the well funded companies that subsequently took turns trying to make it work.

However, few in 2009 predicted that Palm would fail, and many saw Palm's subsequent acquisition by HP as a strong parallel of Steve Jobs returning to Apple (Rubinstein had originally started his career at HP; also, he left Apple for Palm, announced webOS in January 2009, then in quirky homage to Jobs, was named the CEO of Palm in the summer 2009, replacing Colligan). With the prospect of HP's money funding a webOS future, the idea that Palm + HP would most likely end up in failure wasn't a very popular viewpoint.

To most, it appeared that history was clearly repeating, this time with Rubinstein playing the role of Jobs, but in a way that would destroy Apple rather than save it. That's such a tantalizing story that it gets regularly repeated. Every executive (or engineer, or even a designer) that leaves Apple is hailed the same way, despite the fact that departing Apple employees far more often than not end up with failures.

This all happened before

Rubinstein's fellow iPod Senior Vice President Tony Fadell left Apple to create the multifaceted failure of Nest, which Google acquired and lost tons of money on without being able to turn things around despite pouring in tons of additional investment. Ron Johnson, famous for designing and building out Apple's incredibly successful retail stores, similarly blew it trying to fix things at JC Penney. But there's an even greater, high-profile example of an Apple icon leaving to replicate the Apple magic elsewhere without success: Steve Jobs.

Rather than working out like Jobs' return to Apple, Rubinstein's webOS project ended up much more like Jobs' departure from Apple in 1986 and his subsequent formation of NeXT Computer. Jobs had similarly recruited away a team of some of Apple's best engineers and tasked them with building a more advanced "NeXT" successor to the Mac.

Like webOS at Palm, NeXT's engineers (two decades earlier) developed a variety of advanced, innovative ideas that were superior in some significant ways to what Apple was currently selling. But also like Palm, NeXT ended up not being commercially successful. A decade later many of its key executives, architects and other workers ended up back at Apple, along with many of the innovative things they had built outside of Apple. Much of the underlying technologies in macOS X and iOS were salvaged from NeXT.

Incidentally, Rubinstein himself had led engineering of NeXT's hardware in 1990, and was personally recruited by Jobs to Apple in 1997 to fix the existing mess of the Mac's various product lines. So of all the people who could leave Apple and replicate what was working there somewhere else, Rubinstein should have been the ideal candidate: he'd already taken many of the lessons of what had worked at NeXT and brought them to Apple.

Consider these examples (Jobs, Rubinstein, Fadell, Johnson) the next time you read about how any Apple employee leaving the company (for any reason) is destined to replicate Apple's success and destroy Apple in the process. Its the kind of lazy, contrived sensationalism that Wired now excels at.

Deep pessimism for Apple, shallow credulity for Apple's competitors

Many pundits initially agreed with Palm's Colligan in 2006 that the iPod maker would face impossible headwinds in entering the entrenched, hyper-competitive smartphone industry (at least right up until the iPhone began making history). Once Palm's webOS appeared, many loudly hailed the new platform and the company's Pre hardware as being more innovative, more visually appealing and technically superior to Apple's iOS

However, once Palm's webOS appeared, many loudly hailed the new platform and the company's Pre hardware as being more innovative, more visually appealing and technically superior to Apple's iOS (among other things, it featured support for multiple-core processors, a factual first that maintained an exclusive marketing point for a couple months).

After first being wrong about Apple's ability to move from iPods into the entrenched smartphone market, tech thinkers and journalists were again left looking foolish for imagining that anyone else could "walk right in" the same way they'd just watched Apple do it. And again, much of this was fueled by the idea that Palm's webOS and hardware were being led by Rubinstein, known principally for being Apple's 'iPod father," an incredible contradiction of logic.

Why were they so perpetually wrong at every turn? Because they didn't see or understand the full story, just the part Apple's rivals were feeding them. Among other things, they didn't know (or couldn't imagine) that the company that was profitably selling billions of dollars worth of iPhones could match Palm's (commodity!) multiple-core chip, or adopt some of the other original features Palm's webOS introduced, that Apple couldn't hire away talent itself, or more importantly, that Apple had wildly more important strategic advantages than a few novel features that were all relatively easy to reproduce.

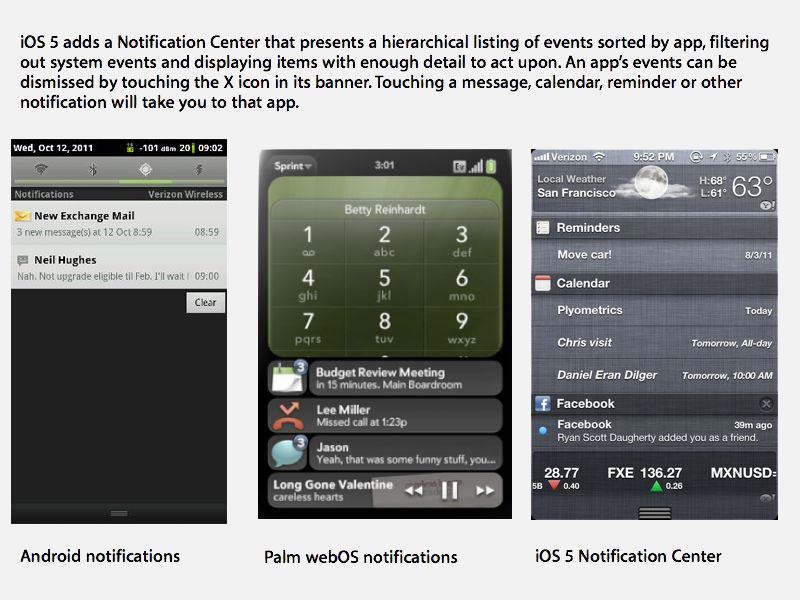

One example: after HP acquired webOS, Apple hired away Rich Dellinger, who had developed Palm's non-intrusive banner notification system, widely regarded as one of the best features of the new platform. It subsequently introduced Notifications Center in iOS 5 (below).

If tech advocacy-journalists really knew anything about the industry they write about, they'd be out creating billions of dollars of wealth themselves, rather than writing up the latest treatise on why Apple is about to wither up and blow away.

The secret of how Apple "walked right in"

While many were fully convinced by the overwhelming "facts" and excited hype supporting webOS— and by the familiar historical pattern of disruption they expected to work against Apple— the reality was that by 2009 Apple had already achieved a strong beachhead in smartphones with iPhone.

Apple was selling phones profitably with a variety of global partners after first having jumped through a narrow window of opportunity with AT&T that had enabled Apple to take a unique, strong position in customer ownership with iPhone buyers.

In 2006, AT&T (then Cingular) had just delicately emerged from a merger of American GSM carriers in an industry dominated by CDMA carriers: Verizon and Sprint. The best phones of the day (in the U.S.) made use of superior CDMA 3G networks; AT&T and its slow 2.5G EDGE had difficulty recruiting phone makers to build desirable American GSM phones. AT&T's network was also different enough from European GSM networks to complicate simply reselling these phones in the U.S.

For these reasons, AT&T gave unprecedented concessions to Apple's iPhone that helped it redefine what a smartphone could be. But by 2009, that window was effectively closed. AT&T already had a strong exclusive with iPhone that was attracting high value smartphone subscribers, so it didn't need to give other phone makers similar concessions. AT&T gave unprecedented concessions to Apple's iPhone that helped it redefine what a smartphone could be

Verizon and Sprint both wanted an iPhone-like offering, but they weren't in desperate enough circumstances to be willing to give Palm the same leverage, freedom and commercial backing to create one. Mobile carriers also helped hobble Windows Mobile and Blackberry— which like Palm were already operating under carriers' rules and therefore had little leverage to change things.

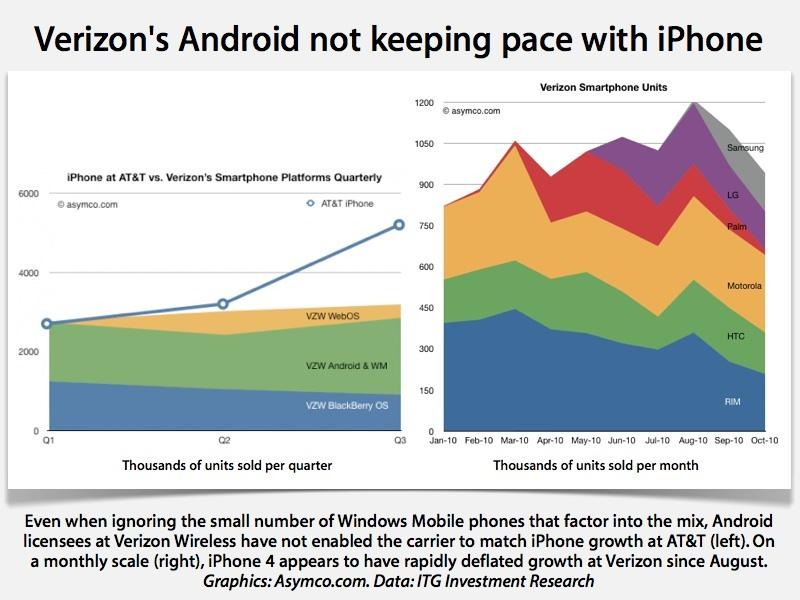

Blackberry tried to "walk in" with its touchscreen Storm at Verizon throughout 2009, but it failed to deliver an iPhone-like draw of valuable subscribers. In 2010, Verizon next banked on Android to provide an iPhone alternative, but Android also failed to attract high value customers.

The inability of Android to attract higher end subscribers seemingly should have been obvious to any observer, but journalists and bloggers alike were fooled into thinking that there was no difference between the candidates, so they voted to support Android because change seemed like a nice idea and so much critical propaganda had assailed Apple and its iPhone as being crooked and borderline criminal, blamed with various farcical sins ranging from making money to killing workers in China via suicide. This delusion, however, lost the popular vote to iPhones.

By the beginning of 2011, Verizon had partnered with Apple on 3G iPads and was ready to launch a CDMA iPhone on its network, extending Apple the same concessions AT&T had in order to get in on iOS business that Palm, Windows Mobile, Blackberry and Android had all failed to deliver.

Apple continued to leverage its unique relationship with carriers that traded iPhone exclusivity for co-marketing and customer access. That included the ability for Apple to directly update the software of its iPhone users, and to regulate and manage how iOS apps were sold. This ended up being monumentally important, but was rarely discussed by tech commentators because nobody who did comprehend what was happening had any real motivation to spread the news of why Apple was commercially winning in smartphones.

Apple itself certainly saw no need to brag up why it was winning. The company would prefer to see its rivals busy patting themselves on the back rather than copying what it was doing. By the time Microsoft and Google realized they should be copying Apple, its tight integration in iPhones and its strict control and regulation of the iOS platform, it was too late.

Not even massively expensive acquisitions of Nokia ($7.2 billion) and Motorola ($12.5 billion) were capable of turning Microsoft and Google, respectively, into a viable vertically-integrated competitor to Apple with enough clout to seek strategic concessions from carriers. Further, the initial efforts both vendors made to create broadly-licensed alternative platforms to iOS undermined and contradicted their belated efforts to deliver a credible integrated mobile platform running on their own self-branded hardware.

Android's PC guys are going to walk right in!

Prior to dumping its "open" strategy to copy Apple's integration, Google's Android promised end users "openness" while also promising carriers, app vendors and manufacturing licensees with the "freedom" to meddle in how various aspects of the platform worked. It was easy to predict that this would result in a mess, but pointing this out was commonly considered a sacrilegious departure from received wisdom.By empowering everyone, Android empowered nobody

Pundits and even legitimate journalists were virtually all hoodwinked into believing a narrow line of propaganda they were fed by Google and Android's proponents: Android was going to be empowering to users, but also to software developers, and independent app stores, and hardware makers, and mobile carriers... all of which actually operated in competition for power. By empowering everyone, Android empowered nobody.

In the same way that 1950's Communism promised to erase the need for government— but only after installing a repressive, onerous form of government to achieve this utopia, Android portrayed itself a selfless collective of open development aiming to create innovative and trailblazing new hardware paired with software secured by "all the eyes" of the developer community, while actually delivering nothing but imitative copycat hardware saddled with insecure software that nobody in the community could actually fix— or even possessed any motive to fix.

Could not be more wrong

In 2011, Google's chairman Eric Schmidt promised that Android would quickly become the first platform that mobile developers targeted, and that developers would be better able to sell their content to Android buyers. Both were wrong.

Google originally insisted that Android would enable third party hardware makers to be more profitable than they had been when they maintained their own proprietary platforms or licensed Microsoft's. More recently it outlined a future where Project Ara modularity would trump Apple's tight integration. Those were also both wrong.

Google also outlined a future where TV would look like a PC internet browser, where video game console titles would be built by a vibrant community of small homebrew indie developers, where Android would enable people to walk around with its search engine strapped to their faces via Glass and where advertising would magically make virtually everything nearly free. Those also turned out to be wrong.

Google not only failed to maintain any control over its platform partners, but couldn't even keep its own promise to use Android to build low cost smartphones. Last year, Google unveiled its "pure, true vision" for Android smartphones in the form of very expensive Pixel models priced the same as an iPhone but missing significant features and running slower.

The same people who acted as a dutiful conduit for all of these fictions about Android are still telling anyone who'll listen that Android is winning because of market share, even though Google and its ads and apps ecosystem has been locked out of China (the world's largest smartphone market) and that Google remains in contention with Samsung, its largest Android licensee by far, while also slipping domestically in U.S. smartphones, much of Europe, and has been isolated into minority share by iOS in technically-savvy Japan of all places.

Also embarrassing for Android is the fact that Samsung has directly worked against Google's Android Wear to establish its own rival Tizen smartwatch platform, even as Apple has devastated both with its own Apple Watch product introduction. So much for selfless Android community solidarity all lined up against Apple and its selfish pursuit of capitalism.

However, the biggest bit of evidence undermining the "grand success of Android" is that across the same period that Apple has earned nearly $1 trillion from iPhone, Google has effectively earned next to nothing from all of its valiant efforts to replace Symbian, Linux or Java ME with Android code, particularly when considering the monumental expenses Google has invested in maintaining and promoting Android.

Source: Asymco

Source: AsymcoCalling Google the leader in smartphones is like saying the U.S.S.R. won the Cold War because it afflicted the greatest number of individuals with its disastrous policies, because its ideologies warmed the hearts of a certain group of intellectuals, and because it achieved a variety of technical firsts, including Sputnik. How incredibly, briefly impressive, yet what incredible cost and misery.

Future windows of opportunity

The unique, limited window of opportunity that AT&T's circumstances offered in 2007, which allowed Apple to redefine the smartphone market with iPhone, didn't last long and won't likely ever occur again in other places. Today however, Apple is in the position of building its own windows of opportunity.

One example of that is its major effort to design and build custom Application Processors, memory and display controllers and other embedded silicon. These efforts are allowing Apple to develop products with features that are difficult for rivals to replicate or undercut on price.

Another window of opportunity Apple is pursing involves corporate partners in software, who build custom iOS apps for their enterprise clients. This includes IBM, Cisco, SAP and Deloitte Consulting.

By working with huge global enterprise developers to create new software that automates industries and creates new efficiencies in business workflow, Apple is creating new markets for its iOS devices that are unlikely to ever switch to rival platforms, the same way that Windows users were hesitant to adopt other platforms a decade ago.

Closing a window on opportunity costs

Beyond seeking out ways to own or control the principle technology in its products— from pure hardware and software to integrated technologies such as Continuity and Apple Pay— Apple also carefully considers the opportunity cost of developing new products in ways many of its competitors don't.

For example, despite currently being the world's largest vendor of tablets, Apple only builds three form factors of iPad. Samsung has created a smooth gradient of tablet sizes stretching from tiny to huge, but that hasn't resulted in leading popularity or profitability. If anything, that busywork appears to have been a distraction.Apple decisively quits developing products that are not successful

Apple also decisively quits developing products that are not successful. Some were abandoned quickly, such as Jobs' iPod HiFi speaker system. Others, like basic iPods after the launch of iPhone, were scaled back and updated less frequently. iPod touch was initially a strategic product that served as training wheels for users of featurephones, or those who were tied to Blackberry or Symbian but wanted to try out iOS without changing their phone. That "window of opportunity" has effectively closed, making it much less important to sell a product that was once very strategic.

The same can be observed of desktop Macs. A decade ago, Final Cut Pro, Logic and Aperture were seen as essential in propping up demand for the Mac as a Pro platform. However, as consumers moved to smartphones for photography and professionals showed a preference for pro apps from third parties, Apple's own offerings have waned in importance. Along with that, Apple's core revenues no longer come from powerful, higher-end desktops. Those models have fallen off of Apple's radar the same way Xserve and Xraid did a few years ago.

It may be that Apple revisits pro Macs with specifications that can't be delivered in the light, thin outline of MacBook Pros or iMacs. But it's at least equally likely that Apple just abandons high end workstations and focuses instead on selling lower cost iPad Pros to a much larger potential market of mobile professionals. Apple could also reevaluate the potential for licensing macOS to other workstation vendors to allow third parties to build higher end Mac hardware in lower volumes than Apple cares to itself.

Some of these changes may be sad to those with a nostalgic history of working with a specific product. But there's plenty of precedence for this: Apple dropped its Apple II line to focus on Macs as a platform with much greater potential (although it took over a decade to completely end sales of the Apple II).

The company similarly slashed away significant efforts in software (including Hypercard, QuickTime VR, AppleWorks and Aperture) to focus on things it excelled at. It spun off FileMaker as an independent subsidiary, and could someday do the same with Logic and Final Cut Pro.

The company long ago backed out of digital cameras and printers, and more recently has apparently given up on selling Apple-branded displays and speakers. Instead, Apple has moved into new markets where it can offer truly differentiated products— notably with Apple Watch and AirPods.

Even within successful hardware product lines, Apple has shifted its resources to focus on products that are either more popular or profitable. While iPhone 5c was successful relative to Android flagships, Apple discontinued it to focus on larger iPhones, then effectively brought it back years later in the low cost, higher end form of iPhone SE. And while iPad mini sold in massive volumes for a couple years, Apple has since focused most of its iPad efforts upon building differentiated, higher-end iPad Pro models that are more profitable and more clearly different than basic small tablets.

Some of this strategy is not obvious in reports of total unit sales. Some of it generates critical opinions and triggers emotional responses. But compared to its peers, Apple is far better positioned to survive 2017, and really faces little threat from Google's expensive Pixel, Microsoft's niche desktop and hybrid Surface PCs, or the generic commodity offerings of Samsung and other PC vendors.

Even if it loses another employee from its current cast of 110,000.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

130 Comments

As somebody who's interested in the products, not the financials, and actually owns an old Mac Pro, I'm still allowed to want an up to date Mac Pro, right? Or should I just shut up about it, because I should care more about Apple's profitability?

Another excellent article by Daniel, that blows the bullshit away, that many other tech writers spew, when they write about Apple. I love reading Daniel’s articles, because he does such a great job of illustrating how wrong those tech writers and pundits have been in the past, about Apple.