In order to run the new macOS Mojave, Macs must have graphics hardware capable of supporting Metal, Apple's modern low-level, low-overhead software that provides access to graphics processing.

Editor's note: The furor about why Apple is deprecating OpenGL has flared up again with the release of Mojave. This piece originally ran in June, but remains accurate and relevant today

Apple's list of Mac hardware supporting the new macOS Mojave is identical to its list of Mac computers that support Metal. More specifically, Metal is Apple's hardware-accelerated 3D graphics and compute framework, standard library and GPU shading language.

Mojave will require at least a Late 2012 iMac or Mac mini, or a Mid 2012 MacBook Air or MacBook Pro. It also of course runs on any new 2017 iMac Pro or new Retina MacBooks (released in 2015), and supports all of the black cylinder Mac Pros (released since 2013). It also supports the earlier "cheese grater" Mac Pro models back to Mid 2010, if equipped with a Metal-capable graphics card.

Why Mojave requires a Metal-capable GPU

Lack of support for Metal graphics is why some of the Macs that are supported in today's macOS High Sierra can't be upgraded to run Mojave. This includes 2009-2011 ("non slim") iMacs; 2010-2011 Mac minis; 2009-2010 plastic non-Retina MacBooks; and 2011 or earlier non-Retina MacBook Pro and MacBook Air models.

The new Mojave drops support for a couple years of non-Retina models, but still supports some non-Retina Macs, as the problem isn't their display resolution but rather their GPU capabilities. Older Mac Pro models dating back to 2010 can be outfitted with new Metal-capable GPUs to run the new release, making it clear Apple isn't just dropping legacy machines to force new purchases.

Drawing a line at Metal-capable GPUs allows Apple to optimize graphics performance— particularly for entirely new software features including multi-user FaceTime and other new iOS-familiar UI features. If you've owned a Mac for 8-9 years, Mojave offers a good reason to upgrade your hardware and join the modern Metal party.

The new Mojave release will officially ship this fall alongside a new iOS 12, watchOS 5 and the new tvOS, following what has been Apple's regular schedule for OS updates for several years now. In advance of this, Apple is offering a Mojave Public Beta program where users can opt in to download prerelease software, test out its new features in advance and report any bugs they discover to Apple.

Metal replaces OpenGL

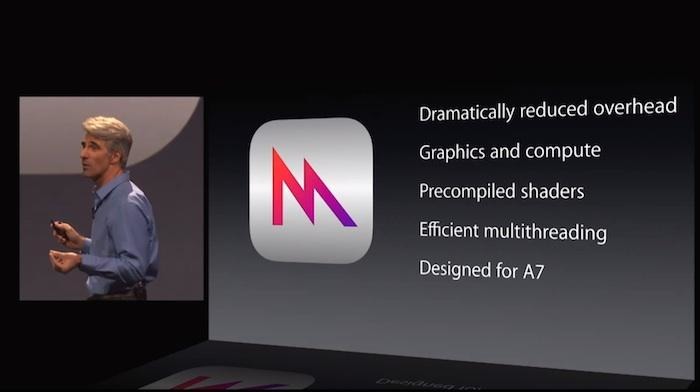

Metal was first delivered in 2014 for the previous year's iPhone 5s to take full advantage of the graphics capabilities of its custom A7 'System on a Chip,' which bundled a 64-bit CPU and independent GPU.

The performance gains from Metal come largely from its optimizations to reduce CPU load, enabling software to much more efficiently make use of the power of the GPU. Metal achieves this using explicit synchronization and shared memory space between GPU and CPU; lower driver overhead, precomputed shaders and up-front state validation; and efficient multithreading, where every CPU thread can send commands to the GPU.

Metal gets its name from its low level of hardware optimization, as it runs on "the bare metal," rather than hovering over a large hardware abstraction layer in the model of cross platform graphics frameworks like OpenGL, which were designed to support a wide range of processors.

Apple initially moved to OpenGL in the late 90s after Steve Jobs announced plans to abandon the company's own QuickDraw 3D, an early project to build support for software graphics rendering into the Mac. At the time, moving to OpenGL allowed Apple to take advantage of existing work already done to build software that enabled hardware acceleration on a variety of different GPUs.

Fifteen years later, however, Apple's iOS had become the largest platform of uniform mobile hardware. In parallel with Metal, Apple launched the first 64-bit custom-ARM CPU, and was also optimizing the generic GPU design created by Imagination Technologies. Going forward, Apple knew that all of its iOS devices would get a 64-bit CPU and an advanced GPU.

Outside of iOS, Android and Windows Mobile licensees were using a wide variety of processors and graphics hardware. They were fated to be years behind in 64-bit CPUs and were beleaguered with cost effective "value engineering" that required devices to ship with underperforming graphics.

Developing the State of the Art in mobile GPUs was an expensive and risky proposition that had pushed one-time mobile GPU giants AMD, Texas Instruments and Nvidia out of the smartphone business entirely.

Apple's goal for iOS was to build extremely high performance graphics capable of rapidly ratcheting up performance and then just as rapidly scaling it down to conserve battery life. It needed the ability to optimize support for upcoming products— notably the higher resolutions of iPhone 6 and 6 Plus, and future models of iPad that would demand more graphics power than most PC laptops had.

Android and Windows licensees had far less ambitious plans. Samsung introduced new high resolution panels but shipped these with basic GPUs running standard Android software. The focus was on bragging specifications, not on actual usability or performance in gaming, creative or computationally intensive software.

In 2015 Apple brought Metal support to recent Macs (with GPUs dating back to 2012, including Intel's HD 4000 and Iris Graphics; AMD's Graphics Core Next GPUs; and Nvidia's Kepler-based GPUs) in macOS El Capitan.

Metal 2 focuses on the ML, AR, VR future

Last year, Apple announced Metal 2 for macOS High Sierra, with improvements including a new shader debugger and GPU dependency viewer for more efficient profiling and debugging in Xcode; support for accelerating the computationally-intensive task of training neural networks, including machine learning; lower CPU workloads via GPU-controlled pipelines, where the GPU is able to construct its own rendering commands and schedule them with little to no CPU interaction; and support for Virtual Reality.

Metal 2 is also supported in iOS on devices using the new A11 Bionic: iPhone 8, 8 Plus, and X models. This chip also launched Apple's first independent GPU of its own design, even more tightly optimized for not just accelerating graphics but also accelerating machine learning and Augmented Reality (which includes applications such as VR and face tracking).

Apple is no longer trying to work within a commodity-graphics community where its own product is just a proprietary variant of an Intel PC, outfitted with one of a several proprietary GPU designs that must all be abstracted to look similar to developers trying to make use of them.

Today, Apple is building its own highly customized silicon— including its own CPU, GPU and Neural Engine, and has to develop bare Metal software to run these both efficiently and at their maximum capacity.

Android and other platforms have begun supporting a community-developed Vulkan framework for graphics that makes improvements over the 1990's era OpenGL, but they don't share the same attainable goals as Apple. Most Android makers are focused on high volume sales of basic phone devices that sell on average for around $200.

The OpenGL deprecation

Earlier this month, Apple's developer documentation advised that active development has ceased for OpenGL and OpenCL on the Mac, and that the APIs will only get "minor changes" going forward.

"Apps built using OpenGL and OpenCL will continue to run in macOS 10.14, but these legacy technologies are deprecated in macOS 10.14. Games and graphics-intensive apps that use OpenGL should now adopt Metal. Similarly, apps that use OpenCL for computational tasks should now adopt Metal and Metal Performance Shaders," the company noted.

In software, "deprecation" means that a feature has been superseded and that while the old version should still work for the time being, it's advised to stop using it moving forward and to prepare for a future where it is removed entirely.

This created a knee-jerk reaction of clickbait warning that "developers" were revolting and waving pitchforks about the announcement. However, the main uses of OpenGL and OpenCL (the GPU-computation framework that Apple originally developed and shared with the OpenGL community) are in porting low level code between Linux, Windows and Macs.

Most modern games with 3D graphics are not hard coded using low-level OpenGL. Instead, developers make use of higher-level graphics "engine" frameworks such as Epic Games' Unreal Engine 4; Blizzard's WoW and SC2 Engine; or Unity Engine. Like Apple's own higher level graphics frameworks such as SceneKit, SpriteKit and ARKit, these already make native use of Metal under the scenes.

That means the games you play today— and the new titles you'll look for in the future— won't really be impacted by the deprecation of OpenGL. They will, however, be greatly accelerated by Apple's latest advances in low-level silicon and the nearly as low-level Metal plated on top. Additionally, Metal is also supporting the deployment of advanced new applications including multiuser FaceTime in the macOS Mojave Public Beta.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

-m.jpg)

137 Comments

Very informative, thanks.

Question, what is the impact on the latest Macs running Windows 10 and beyond under Boot Camp, I assume none and Window will just continue as is, even on the latest Macs?

Can someone with deeper insight tell whether older GPUs are that bad that they could not support Metal if "anybody" would made drives? Or count with them when coding Metal? Older versions MS DirectX is running on much worse HW I woudl say.

This still makes no sense at all. There is no reason why Apple can't support their native SDK (Metal) and OpenGL. Microsoft has been doing this for decades with DirectX.

The majority of game developers won't bother with creating Metal versions of their rendering engines. There won't be enough customers to justify it.