Apple's remarkable success in iTunes and its App Stores bears striking similarity to another example of a platform developer investing in its own ecosystem: transit Value Capture. App Store Value Capture has changed the game for Apple, and is now fueling a faster rate of revenue growth for the company than all of its hardware segments combined.

Apple gets trained to leave the station

The term Value Capture applies to rail and transit operators that are given the rights to develop the land around their stations. America's intercontinental train routes were developed by railroads that were deeded land along their planned rail lines. These plots were then sold off or developed, capturing some of the value added by the fact that that land was adjacent to the transportation service the railroad had built and was operating.

Today, while most of America's current transit systems (from Amtrak to BART) are now on the brink of failure and are often in worse shape than what you find in third world countries— despite the high tax subsidies paid to sustain them— there are many examples around the world of public and private transit operators performing extremely well simply because they were given the rights to develop the land around their stations, leading to extremely lucrative revenue sources that sustain their operations and growth while they provide efficient transportation services to the public.

With iTunes, the App Store, iCloud and Apple Music, Apple has similarly effectively captured some of the value its hardware platforms have created. This ecosystem of content is about to get a lot larger as Apple ventures beyond third party music and movies and begins creating its own digital content.

We know this because we've already seen what happens when Apple moves from selling other people's content (iTunes music, movies and Audible books) to creating a new native form of content that it can sell exclusively: software.

Selling or reselling apps has been fantastically more lucrative for Apple than reselling licensed content that already exists and can be bought in many other forms. It's not hard to see why Apple is now aggressively engaging in TV and film content production to sell new content exclusively to its platforms spanning more than a billion premium device users.

Blinded by Windows

As the world began to notice the success Apple was seeing with iTunes and iPod in the early 2000s, established players all scrambled to get into (or regain control) of both hardware devices and media content stores. Fifteen years ago, tech media writers almost unanimously agreed that then-giants Sony and Microsoft (and even minor players including iRiver, Creative, Napster and Microsoft's PlaysForSure licensees) would trample Apple out of the music business. Why? Because Windows had beaten the Mac a decade earlier.

Those writers were as wrong then as they are today, largely because most of what passes as "journalism" in the tech world is really just rival companies' press releases paraphrased by people who can't get real jobs and have no actual experience working in the industry— or apparently even observing what's happening and what has recently occurred.

Once a columnist or pundit is indoctrinated into an ideological corner by some firm's PR department, they will believe in their personal Stockholm kidnappers no matter what nonsensical, contradictory gibberish they are told. One example: at the height of Apple's iPod, Microsoft told the media that it was launching Zune in such a way that it would somehow not compete with its own PlaysForSure partners' device sales (only Apple's iPods!) and the press gobbled it up and dutifully syndicated it out to their audiences, essentially without criticism.

Despite being plagued by a series of real problems, the tech media largely believed that Zune could successfully compete with iPod without hurting Microsoft's parallel PlaysForSure business.

Despite being plagued by a series of real problems, the tech media largely believed that Zune could successfully compete with iPod without hurting Microsoft's parallel PlaysForSure business.When Apple began replicating its iTunes success in the iPhone App Store, the same set of writers all again assumed that Microsoft, Palm, Google, Nokia, Sony, Samsung and everyone else that was selling phones and phone software prior to Apple would regain their positions and push Apple out of business because "look back at the 1990s and see how the Mac was sidelined by Microsoft's Windows PCs."

The Schtick

When Google told its sycophant media partners that it was building its own Google-branded devices that would somehow (just like the Zune) compete with Apple's iPhone while having no negative impact on its Android partners, the press again gobbled it down like a dog eating up the toxic vomit that had just caused it to throw up a minute ago.

Even more remarkably, the various teams of media writers carrying water for Google have repeated the idea that every Google-branded phone was somehow "the first real Google Phone" over and over across the last decade, from the HTC G1 to the Nexus One to the Moto X 1 to the Pixel 1 and every model in-between.

Fool me once, shame on me. Fool me literally every time you release a phone between 2008 and 2018, and it's obvious that I'm willfully playing along in this game of fooling people.

When Google slashed the prices of its poorly selling Moto phones, tech media luminaries pretended this was a genius strategy to hurt Apple's profitability rather than a clear sign of inept failure by buffoons

When Google slashed the prices of its poorly selling Moto phones, tech media luminaries pretended this was a genius strategy to hurt Apple's profitability rather than a clear sign of inept failure by buffoonsWhen it became clear that a decade of Nexus, Moto and Pixel introductions had zero impact on Apple's iPhone and iPad sales, the tech media again turned to hear Google explain that despite its fantastical billions in hardware investments, it wasn't really trying to do anything anyway, so it had succeeded in failure and the whole exercise had really been such a fun adventure— an insane idea that was met with the kind of worshipful applause usually only heard by a naked emperor in a land of morons.

The same people also construct illogical loops that insist that Google's massive multi-billions of dollars plowed into boondoggle acquisitions like Motorola and in building and maintaining teams of engineers who create everything from custom silicon to advanced software and cloud services— all specifically to support Google-branded devices that end up as total failures in the market— are a good use of resources because Google has so much extra money laying around it can afford to burn $5 billion here and $12 billion there and then pay a $5 billion EU fine without blinking— the same way that it was no big deal that Samsung had vaporized at least $5 billion in its Galaxy Note 7 battery supernova imbroglio.

They then turn around and audibly gasp that some nobody constructed an estimate that assumed Apple may have spent as much as $5 billion across the last decade building its permanent Apple Park facilities, and wonder how long the company can possibly hope to stay in business when it arrogantly spends piles of money on itself like that.

And then they wagged their fingers at Apple's +$200 billion cash hoard, and explained that investors don't like the idea of a public company sitting on that much money without gaining a significant return on that capital. And then (it never stops) they point at the $3 billion acquisition of Beats and complain that Apple has no business expanding its audio hardware offerings and pushing into music streaming because good-god that's a lot of money to spend on a profitable brand with popular products that sell far better than any Google-branded phone ever has.

Half of the puzzle misses the big picture

Many of these ideas are based on classic tenets of conspiracy theory: "doubt the facts you know, and worry about possibilities that are unlikely, because what if they are true?" The notion that Apple is dangerously close to failure stems from "its entire business is predicated on doing what it has successfully, consistently done for years, but what if it can't do it forever?"

There are two problems with the supposedly irrefutable logic of "commodity always wins." One was the idea that hardware is easy, and the other was that software is easy. In reality, both are extremely hard to do well, but also hard to sell— and often can be difficult to even give away. Perhaps hardest is the effort to integrate hardware and software seamlessly.

Despite its stature in PC licensing and its Xbox franchise, Microsoft couldn't build a commercially successful media player despite plowing billions into its Zune brand. Despite a storied history of creating the state of the art in home audio, boomboxes and portable players, even Sony was unable to rival Apple's iPod or introduce a great media store experience. Other first movers in media player hardware couldn't keep up, and most every effort in media stores couldn't stay in business.

In part, these failures were often the result of companies trying to copy part of Apple's business: either music player hardware without a useable store, or a media store without consistently great hardware integration. Apple's teams were doing two difficult things— and then integrating them to work well together.

As iPhone emerged, Apple continued its integration model while virtually everyone else in the industry lined up to be licensees of Windows Mobile or Android, referencing the precedent of Windows in 1995 while ignoring the current state of Windows PCs being clobbered by Macs in profitability— and what had just occurred within the world of iPod and iTunes.

While the most apparently obvious problem was the lack of smooth integration occurring between licensees and their platform vendors, a similarly huge issue was that in a world of disjointed hardware and software development, there was no ability for anyone to cash in on Value Capture in the way Apple could.

Value Capture versus the appeasement of software partners

One obvious difference between Macs in the 1990s and iOS in the 2000's (at least with the 20/20 vision of retrospect) is that Apple had very limited Value Capture in place for the Macintosh. While Apple did all the work of building and maintaining its Mac platform, the real beneficiaries were Microsoft, Adobe and other third party developers that effectively did nothing in return but "support" the Mac OS with their software.

Apple was so desperate for this third party "support" that it often actively held back from building and bundling its own first party software with Macs, to avoid any conflict with the developers it was courting to support its platforms. While Macs remained marginally successful despite being marginalized by Windows, Apple's other platform from the 90s, the Newton MessagePad, was unable to woo major development at all.

Part of this was the result of Apple being so careful not to compete with its third party developers. This behavior seemed sensible back in the 1980s and 1990s, when hardware makers relied on third parties to "support" their platform, knowing that without such support they would become as irrelevant as Atari or Amiga or OS/2. Apple's extreme efforts to avoid conflicts with its software partners resulted in the company spinning off most of its internal software into the Claris subsidiary back in 1987.

But without getting into software itself and creating titles that sold its own hardware, Apple's Macs, the 1994 Newton and even its 1996-acquired, NeXT-based macOS X seemed doomed, as all existed at the whim of third parties that might at any time simply abandon Apple's platforms. That's exactly what Microsoft did when it got Windows to the point of standing on its own in the mid 90s, and Adobe and others subsequently followed suit, taking their Mac software to the larger market of Windows PC users.

Apple learns a lesson - from Microsoft

While Microsoft didn't worry about Apple's feelings when it worked to crush its former partner by freezing development of Office apps on the Mac, it also turned around and screwed over its own PC developers. Unlike Apple's careful efforts to avoid stepping on its third party developers' toes, Microsoft actively attacked its primary DOS PC developers (including dBase, Word Perfect and Lotus) by launching Windows 95 with its own bundled Office 95 apps.

And when companies like Netscape unveiled entirely new apps (like the web browser), Microsoft quickly worked to kill them off with its own first party, bundled copies (Internet Explorer). Microsoft's relentless drive to own Windows and capture as much value as possible from its platform was completely different than Apple's timid efforts to help its third party developers and avoid competing with them at all cost.

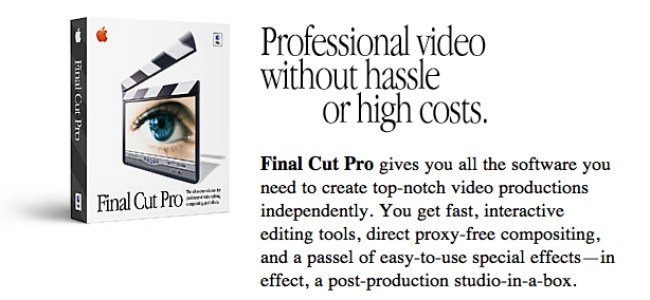

Apple appears to have accidentally figured out the importance of owning its own software. As Adobe began cold-shouldering the Mac in the late 90s and throwing its support behind Windows, Apple identified KeyGrip, a QuickTime-based video editor project at Macromedia— slated for cancelation— as something it should step in and save in 1998.

When it couldn't find a third party software partner to take over the development of the software, it released it on its own as Final Cut Pro. That title turned out to be essential in helping Apple sell its PowerMac hardware in new markets.

Because the rest of the world was effectively abandoning the Mac, Apple finally realized that pandering to third parties wasn't a sustainable way to maintain its ecosystem. It subsequently acquired what would become iTunes in 2001, and used the app to sell iPod. Apple then got into music production with Logic in 2002.

Apple's acquired Pro Apps spawned the consumer titles iMovie and GarageBand, and helped launch two new suites of Apple-branded apps: iLife creative tools and iWork productivity software.

Apple also actively began building and maintaining its own Mac development tools with Xcode starting in 2003, rather than delegating this task to third party development tool vendors as it had in the past. And as Microsoft and Netscape became unreliable web browser vendors on the Mac, Apple launched its own Safari browser, also in 2003.

By expanding its ownership of an increasing amount of "land" around its "stations," Apple was not only gaining independence from the whims of its software partners, but also setting itself up to make bold changes that didn't require the approval of its ecosystem. That was a huge shift from the era of 1997-2003, when Apple sought to transition from the classic Mac OS to the new macOS X Yellow Box, but was rebuffed by major developers who insisted that Apple slow down and do far more work to support their own existing legacy code.

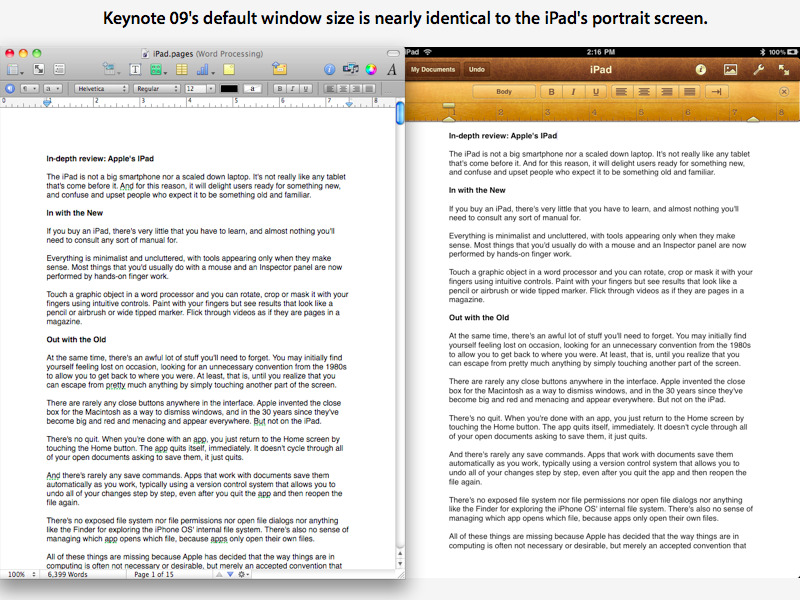

Once Apple gained ownership of its core platform technologies (from the OS to its development tools to the web browser and core bundled apps ranging from Mail and Calendar to iPhotos), it gained the ability to rapidly make major shifts like the jump from PowerPC to Intel processors (literally overnight, compared to the many years eaten up in the previous, incremental transition from 68K to PowerPC), and then (the next year!) to ARM processors supporting iOS as an entirely new mobile platform.

In 2010, when Jobs introduced iPad, he could show it off with a suite of Apple's own iWork productivity apps, along with the Safari browser, Mail and other essential apps, without waiting endlessly for third parties to decide whether or not to invest in the entirely new table platform the way Apple had with the Newton in the 1990s.

Rather than scaring off third party development, as Apple had feared doing in the 80s and 90s, the attention Apple created for its platforms among consumers stoked developers to join in building custom apps for iPhone and iPad. And the App Store model Apple created helped the company to benefit from the value of the platform it had created.

Apple had gained Microsoft's flexible "Value Capture" market power but had a better sense of how to use that power to effectively achieve valuable goals. Note that at the same time, Microsoft had greater leverage over PCs but failed to effectively transition to new processors or to competently bridge its desktop model into the mobile world of phones or tablets. Microsoft even struggled to get its own Office working on its own mobile platform.

Sherlocked Holmes and the case for Value Capture

Apple's increasing efforts to gain control over its own platforms and exercise Value Capture have often been rebuked by the various people who didn't benefit from this trend.

When Apple released its web search tool Sherlock 3 for the Mac back in 2002, it encroached upon similar features already supplied by a third party utility named Watson. Outcry over Apple "sherlocking" its third party developers continued when Apple added a web-based layer of desk accessory-style widgets to the Mac, similar in appearance to an existing product called Konfabulator.

Apple and its Mac platform were seen as a parent that owed its children (third party developers) everything, and must deny itself of every pleasure to keep its children alive, safe and well fed. Except that third party developers weren't children, they were independent business people. Apple had every right to build its own software and create new markets capturing the value of it had created with its platforms. It didn't owe its developers anything more than Microsoft owed its DOS PC partners— the very companies it chewed up and spit out to launch Windows.

Rather than being helpless children, some of Apple's partners were ruthless and brutal agents that would take everything Apple gave them before stabbing their host platform in the back, the way Microsoft and Adobe (and so many others) did.

Microsoft really did have to lose

When Apple settled with Microsoft in a 1997 deal that forgave Microsoft for stealing Apple's QuickTime code and infringing its patents, in exchange for a public show of investment and a five year commitment to create new Mac apps, the deal was portrayed as Microsoft mercifully saving Apple and Apple getting over its embittered fantasy of beating Microsoft. The reality was far removed from that.

At the time, Steve Jobs famously stated, "if we want to move forward and see Apple healthy and prospering again, we have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win, Microsoft has to lose. We have to embrace a notion that for Apple to win, Apple has to do a really good job. And if we screw up and we don't do a good job, it's not somebody else's fault, it's our fault."

Most of the people who heard those words took away nothing more than the idea that Jobs was saying "Microsoft doesn't have to lose." But that's not at all what he said. He said "Apple has to do a really good job," an idea that suggested that Microsoft would indeed lose something. And it did.

In the 1997 agreement, Apple was stocking up provisions to reach a future where it could be successful without depending on or appeasing Microsoft. It was also working on doing "a really good job," something that necessitated that Microsoft would lose its current status in several areas.

Apple got QuickTime codified as the storage standard behind MP4 in 1998, erasing the value of Microsoft's rival work with Advanced Streaming Format. Apple then made moves in music to derail everything Microsoft had built— from audio codecs to media player OS licensing. It then moved into web browsers with Safari and created the world's most popular mobile browser, denying Microsoft entry into mobile markets. And the App Store has cracked open Microsoft's Office monopoly with new specialized app tools that disrupted the status quo in productivity suites.

There is no way Apple could have reached its current position without Microsoft losing in digital media, in music, in apps and in mobile and wearables. Jobs wasn't saying 'Apple had to win without Microsoft losing.' He was saying Apple had to win on its own merits, rather than blaming Microsoft for its current predicament.

If Microsoft hadn't lost out to Apple in achieving Value Capture of the software market surrounding the most valuable platform in computing, Apple wouldn't today have a trillion dollar valuation.

App Store as an R&D facility

Apple has since appropriated a variety of third party concepts that originated among its developers (or on other platforms). In some cases, it has licensed, acquired, or acquihired the talent and code required to deliver its own product (such as with Siri). It other cases it hasn't needed to, because good ideas that aren't protected by copyright or patents are open for everyone to independently implement.The fact that Apple operates the world's most commercially successful software store gives it unparalleled insight into what affluent consumers want and what they will pay for

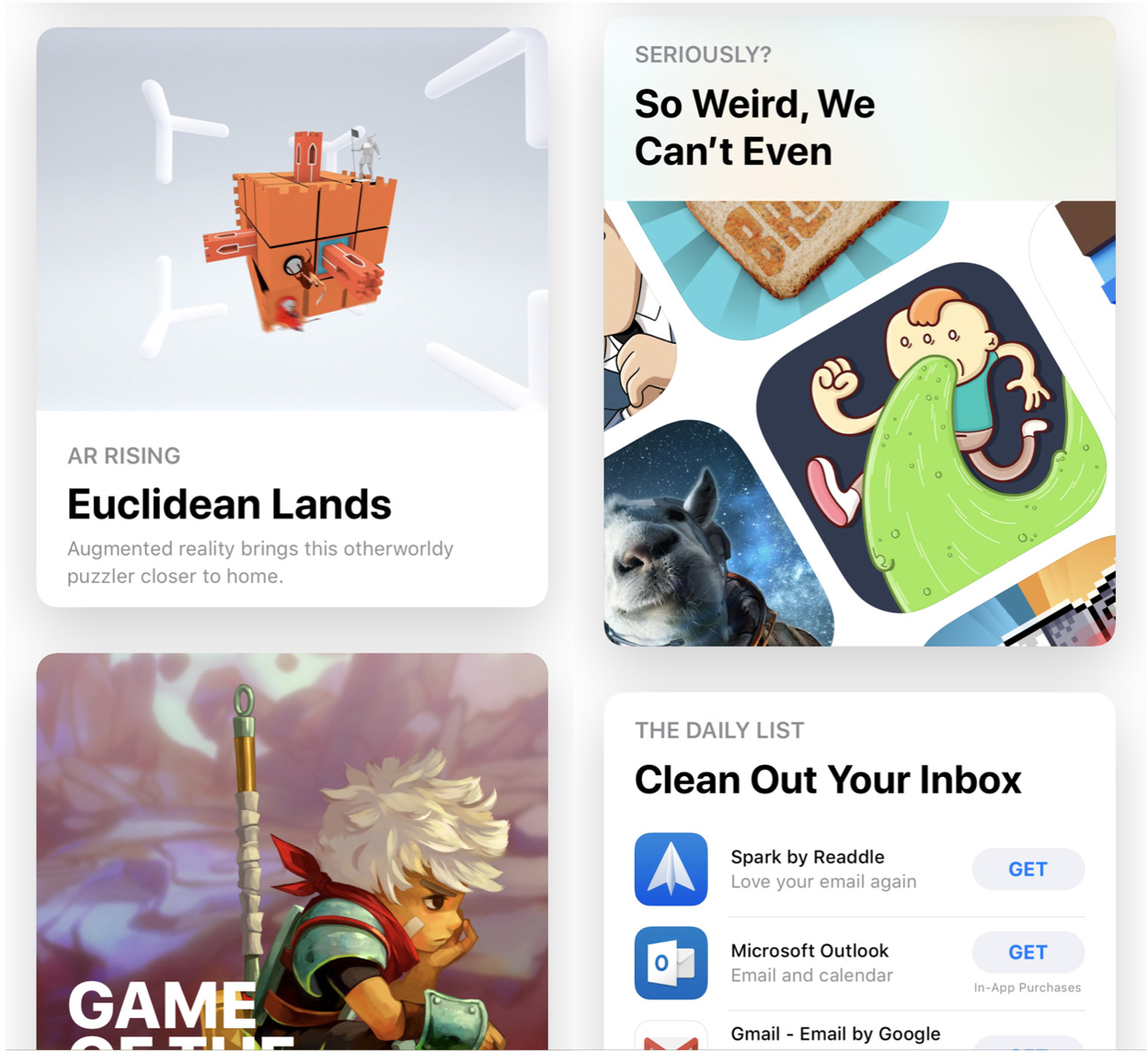

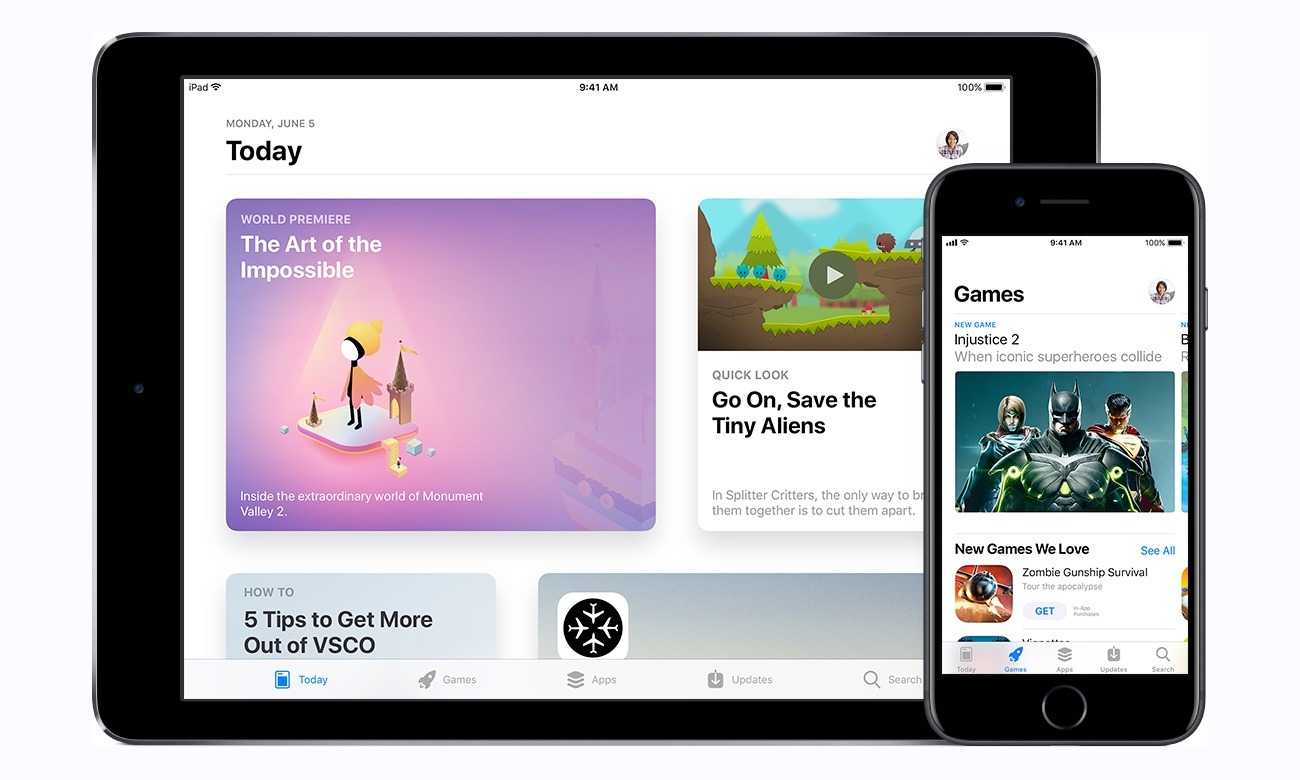

The fact that Apple operates the world's most commercially successful software store gives it unparalleled insight into what affluent consumers want and what they will pay for. The App Store is a fertile testing ground that gives Apple a steady stream of new innovative ideas to harvest. It is essentially a massive research and development lab funded by outside capital, providing Apple with mountains of valuable data.

This hidden value of the App Store appears to be ignored by analysts and the media, who often seem to prefer to believe that Google is "winning" because it is servicing higher volumes of downloads to a far less valuable market of users who don't care to pay for software and trend toward cheap hardware, contributing analytics data that is virtually worthless for any purpose, particularly in guiding the development of premium hardware and valuable subscription services.

It's no wonder Google's Pixel phones, netbooks, and tablets aren't capturing the interest of affluent users. Google lacks the data needed to design products that premium users want. Google has tons of data on low-end users who are content with ad-supported services with no protection of their privacy. That's not earning the company any standing in premium hardware anymore than McDonalds has any chance of wooing in foodies who are seeking to avoid processed food.

Meanwhile, Apple's Value Capture directly generated more than $9.5 billion in Services revenue in the last quarter, growth of 31 percent over the year ago quarter. In the same quarter, Facebook reported total revenues of $13.2 billion, and warned that "we expect our revenue growth rates to decline by high single-digit percentages from prior quarters sequentially in both Q3 and Q4."

Investors have priced Facebook as if its worth more than half of Apple's entire business, despite the fact that Apple generates over four times the revenues and is growing across existing product categories, into new markets including wearables and Services, and globally in every major market. For Facebook, there's little additional real value to capture from the advertising service it has created.

Apple is just getting started in Value Capture.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

-m.jpg)

32 Comments

Horace Dediu has stated in the past, that Apple gets a dollar on day, on average, from every user, which includes Hardware and Services.

Apple’s hardware are vending machines, their services are the snacks.

I hope they’ll focus more in professional use and create the equivalent of G Suite. Their current offering on that front makes no sense.

A lot of people bemoan Apple’s apps as being not very powerful. For example they rail on Numbers because it doesn’t support AppleScript very well and thus it can’t compete with Excel but I’ve not seen anything that proves that. The only thing that Excel seems to do that Numbers can’t is read data from another spreadsheet. But I can do thing in Numbers that requires Visual Basic knowledge I’m Excel.

Take for example checkboxes. In Numbers I simply change the format of the field to be a checkbox then create a formula that references that checkbox. To do the same thing in Windows you have to write a screed of VB code which is time consuming and daunting for your average person.

In other words Apple’s software is at its most powerful when they are making complex things easy. People fail to realise this and just rail on Apple for writing simplistic apps.

Of course the likes of Microsoft and Adobe will make this point louder in order to sell their own software but frankly they are pretty pathetic software. People want to use software and not learn to code.

Apple’s apps aren’t perfect but they are for most people and most people is who Apple is aiming for because most people spend money.