The formerly universal consensus that widely licensed software (like Windows) would always win out over integrated hardware products (like the Macintosh) has finally reached a definitive end, years after being proved wrong.

A long monopoly game finally ends

At some point in the 1990s, the supremacy of broadly licensed operating systems became an unquestionably held dogma.

This began as a reaction to the success of Windows, but was reinforced with the failure of every integrated hardware product that failed in its wake, including the Acorn Archimedes, Atari ST, Commodore Amiga and BeBox. Apple's Macintosh was the only non-Windows PC to survive the decade, but the company was still labeled "beleaguered" for daring to remain in business.

The notion that an integrated PC wouldn't and couldn't sell without Windows even caused Apple's 1990s leadership to pursue Windows-like licensing programs, first with the Newton OS and then with the Mac OS in 1995.

Other companies also tried to introduce broadly licensed Windows alternatives, most notably IBM's OS/2, but also Sun's Solaris and Steve Jobs' NeXTSTEP for Intel PCs. Nobody was willing to question the idea that the only way to sell an operating system was Microsoft's Windows Way, despite the fact that nobody was really able to successfully copy Microsoft either.

It seemed that nobody was willing to question the idea that the only way to sell an operating system was Microsoft's Windows Way, despite the fact that nobody was really able to successfully copy Microsoft either.

In reality, Microsoft didn't happen upon the True Way to sell technology. It simply won by cheating, erecting a monopoly where nobody else could actually play. Software alternatives were locked out of the market by illegal tying agreements, while Microsoft's hardware "partners" were duped (for decades!) into funneling most of their profits to Microsoft.

This continued for so long in large part because the tech media overwhelmingly refused to judge the PC game as impartial journalists and instead largely assumed the role of Microsoft flatterers, weaving rich tapestries of prose to glorify the Windows Empire's fine New Clothes.

Technology shifts, but the world refuses to notice

The technology world was so thoroughly convinced that Microsoft's Windows was the One And Only Way to sell computing that nearly everyone refused to observe or consider the accumulating data conflicting with this "common sense" opinion.

The first evidence that broadly licensed software wasn't necessarily a superior model for selling technology came from parallel efforts to be like Microsoft: IBM, Apple, Sun and NeXT all failed to replicate the Windows model with their own licensing programs.

Even more persuasive should have been the clearly observable inability of Microsoft to spread Windows Everywhere. A string of Windows failures that began early in the 1990s was carefully excused and ignored by the tech media in its collective refusal to be anything but an extension of Microsoft's PR department.

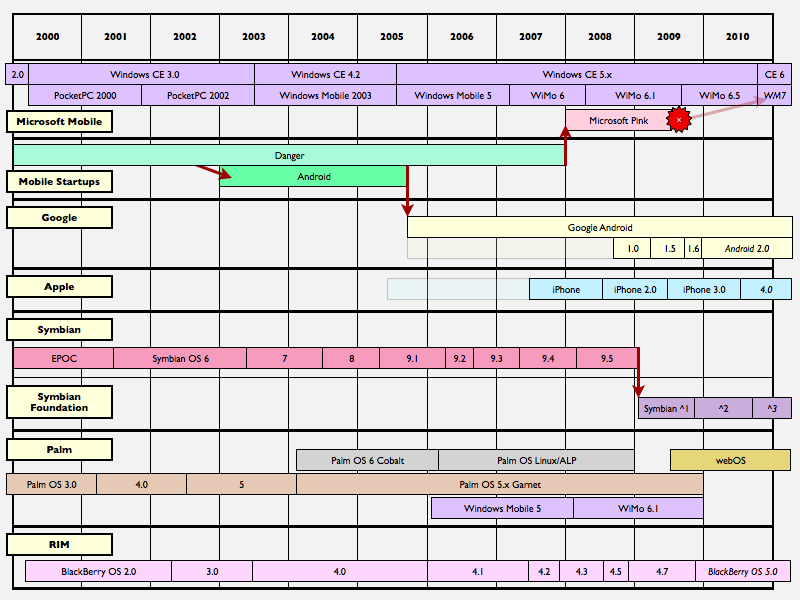

From Windows for Pen to WinPad to Windows Handheld PC to Windows Palm-sized PC and Pocket PC to "Windows Powered" (and other Windows CE initiatives including Mira Smart Displays and Media2Go/PlaysForSure/Zune and Windows Mobile/Windows Phone) to Windows Tablets, Slate PC and UltraMobile PCs, Microsoft's every effort to duplicate its Windows PC model in new product segments or form factors simply fell flat on its face.

Palm proves Windows doesn't work: 2003-2007

A third experiment testing the supremacy of broadly licensing a technology came in the early 2000s, when Palm's PDA business began to falter, much like Apple had a decade previously. Palm's situation was nearly identical to Apple's in the early 1990s: it had a popular integrated product saddled with aging system software and an increasingly obsolete CPU architecture.

Everyone offered the company the same advice they'd offered Apple, invariably recommending that it split its hardware and software businesses, broadly license out its software like Microsoft, and perhaps even license Windows from Microsoft.

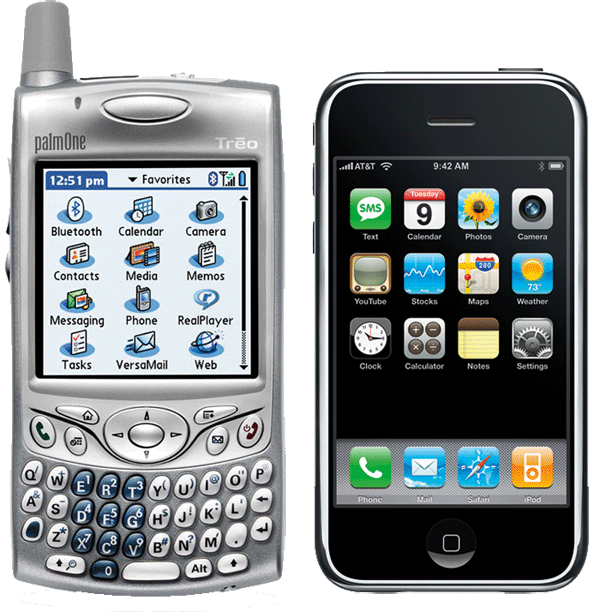

After briefly duplicating many aspects of Apple's turnaround strategy being accomplished in parallel under Steve Jobs (Palm even brought back its own founder, Jeff Hawkins, in a move to enter the new smartphone market being pioneered by Hawkins' Handspring Treos), the company then shifted to a Windows Enthusiast game plan.

That proved disastrous. Licensing Palm OS briefly appeared to work (Palm even signed up Sony as an enthusiastic partner) but soon failed; Sony backed out by 2004. Splitting the company into hardware (palmOne) and software (PalmSource) created confusion and support headaches for customers, with no clear benefits.

Licensing Windows Mobile from Microsoft and selling that alongside its own Palm OS created even more confusion, and resulted in a slashing of Palm's own installed base. But it wasn't Microsoft's Windows licensing that finally killed Palm: it was an integrated device: Apple's iPhone.

Apple proves integrated products can work: 1997-2007

A decade prior to the release of the iPhone, Apple began a turnaround under Jobs that refocused the company on doing the unthinkable: selling integrated products in a Windows-dominated world. Among Jobs' first decisions were the termination of Apple's Newton and Mac OS licensing programs.

Jobs then focused Apple on doing something that nobody else in the PC business was doing: creating innovative, tightly integrated packages of hardware and software.

From the striking new iMac in 1998 (above) to strategic investments in PowerBooks and iBook notebooks, Jobs turned Apple from being a "non-Windows compatible PC" maker into a fashionable, innovative, trendsetting designer of a series of new computing products that began leading, rather than following, the rest of the PC industry.

In 2001, Apple entered a new market with iPod, leveraging internal assets (like Firewire) and external assets (like Toshiba's compact hard drive and Pixo's embedded OS) and integrating them all into a desirable, functional, valuable package it could sell at a profit.

Oddly, this is the basic strategy of nearly every product designed outside of the technology sector, but was not really being pursued by anyone else inside the tech world, and in particular not among the blind OEMs clinging to Microsoft for direction and vision.

By 2003, Apple's iPod was globally popular and monumentally profitable. Yet its primary competitor, in the minds of the tech media, was a broadly licensed technology platform being fronted by Microsoft: PlaysForSure. Read any of the tech punditry from that period for some hilarious mass delusion about how Microsoft was guaranteed to overtake and trounce Apple's iPod.

Instead, iPod stomped PlaysForSure into the horse manure. Microsoft had failed repeatedly before, but never in a way that mattered, and never to an integrated product (the closest experience being the short lived success of the Palm Pilot, which as noted above, was successfully hoodwinked into carrying Microsoft's water to the point of exhaustion).

Apple's thrashing of Microsoft's broadly licensed PlaysForSure platform with its own integrated product continued for years while the tech media refused to believe what it was observing, from 2003 to 2006. Meanwhile, Microsoft embarked on the unthinkable: it began copying Apple's integrated product strategy with its own Zune.

Unsurprisingly, Microsoft was as bad at playing in Apple's home court as Apple had been in trying to play by Microsoft's platform licensing game. The Zune was an embarrassing failure across its several generations.

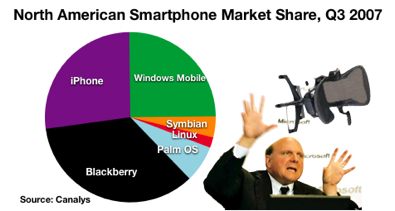

In 2007, Apple brought its integrated product savvy into direct competition with Microsoft's decade old experiment with Windows CE/Windows Mobile in the arena of smartphones. After its first full quarter of sales, Apple's iPhone had surpassed Microsoft's U.S. smartphone sales, despite Windows Mobile's half-decade head start in smartphones.

Microsoft enters integrated products: 2008-2013

In an effort to remain competitive with Apple's iPhone, Microsoft did something unpredictable: it acquired a mobile phone hardware company. No, it did not start with Nokia.

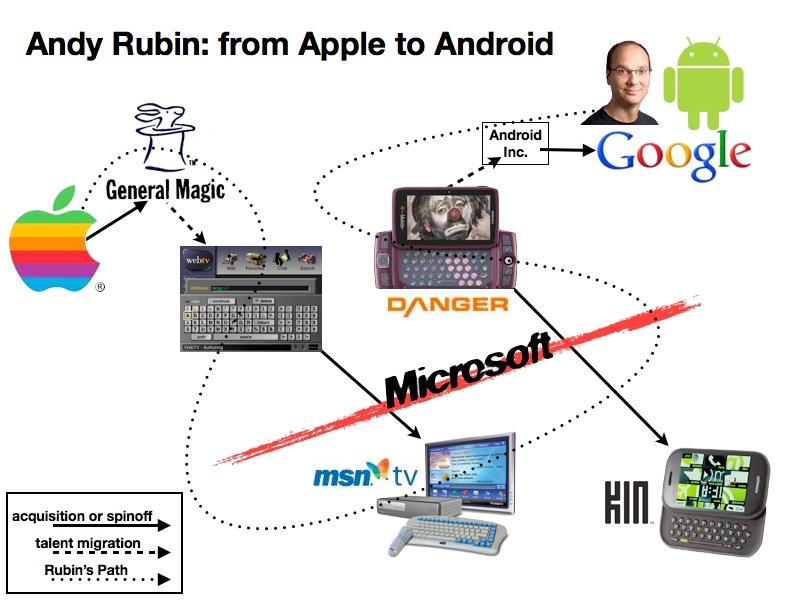

In 2008 Microsoft spent half a billion dollars to acquire Danger, Inc, a startup co-founded by Andy Rubin. Danger was essentially the predecessor of what became Android: a Linux/Java based integrated mobile product.

Rather than playing up Danger's strengths (Danger's Sidekick was at the time a popular, cloud-centric mobile texting device), Microsoft did to it what it had done with a series of other hardware-related acquisitions, including WebTV: it forcibly fed Windows down its throat like a unlucky duck being raised for foie gras.

After destroying Danger's credibility by bungling its existing cloud infrastructure, Microsoft converted Danger into an integrated product so terrible that it couldn't remain on the market for more than 48 days. This was KIN, a product so dreadful it made the Zune look like a resounding success in comparison.

While Microsoft diddled with KIN under the Pink Project, Apple had been developing its third major integrated product success with the iPad. To compete with this rumored tablet, Microsoft rushed to market "Slate PC" in a partnership with HP, its long time Windows PC licensee partner.

Slate PC beat iPad to market, but it was so battered against the ground by iPad that only a few thousand of the devices were even built. That didn't stop the tech media from inventing excuses for it or trying to explain how Microsoft was really only trying to achieve failure in tablets because it didn't need to compete, being seated on top of the Windows Monopoly and all.

This myopic, willful ignorance and excuse-centric, platitude-barfing flattery of Microsoft's every misstep might have made sense in the 1990s, but by 2010 the kowtowing tech media's fawning over Microsoft was as unnecessary as the lickspittle sycophants of the royal court after the revolution had beheaded their monarchs.

Three years later, all Microsoft has done is port its desktop Windows to ARM under the "RT" brand and deliver two versions of a new Surface Tablet PC hybrid that nobody even wants one of. Even Microsoft's licensees don't want Windows RT, and they aren't that enthused about the Zune/Windows Phone/Surface inspired version of Windows 8, either.

All that's left for Microsoft to do now is acquire the remains of Nokia and complete the foie gras hardware-husbandry that last produced the stillborn KIN. If it weren't for Android, the broadly-licensed enthusiast media wouldn't have anything at all to breathlessly fawn over.

Google enters broadly licensed platforms: 2006-2013

Given that Microsoft's one hit Windows wonder was running into clear troubles with Longhorn/Vista by 2006, it's hard to explain in retrospect why the tech media was so completely unaware of the transformation taking place in its own industry.

The tech media was so willfully blind to the overwhelming sales success of millions of iPods and a similar erosion of the mobile industry (then dominated by the broadly licensed Symbian and JavaME) by iPhone that it applauded Google's Android project as a successor and heir apparent to Windows Mobile.Android was (and still is!) broadly viewed as fated to inherit a divine right to the Microsoft Windows crown in a post-revolution world.

Android was (and still is!) broadly viewed as fated to inherit a divine right to the Microsoft Windows crown in a post-revolution world where that crown remains firmly attached to a beheaded head still gasping for relevance and obeisance (although Steve Ballmer isn't expected to survive the year).

What started out as simply grading Android on a curve as a scrappy underdog turned into a deifying worship of a clownish green mascot and a reverence of Google's every move, regardless of its eventual failure, from the company's flag waving support for the doomed Adobe Flash to the Google Wallet/NFC fiasco to its ineffectual WebM shenanigans.

Google's Android began running into the same integration and fragmentation problems that had previously complicated Windows PCs, Apple's Mac Clone program, Palm's licensing initiatives and Sun's JavaME. From vendor bloatware to device and app incompatibles, things got so bad in Android land that Google resolved in 2010 to solve them the same way Microsoft had with the Zune just a few years earlier.

Google enters integrated devices: 2010-2013

Google hailed its HTC-built Nexus One as its first experiment in "pure Android." After that experiment flopped, it teamed up with Samsung to introduce two more flops: the Nexus S and Galaxy Nexus, then partnered with LG to deliver the Nexus 4, a fourth Nexus to not sell very well.

But no criticism, please! The broadly licensed platform monarch demands your groveling support. Viva lèse-majesté!

At the same time, like Microsoft, Google also wanted Apple's iPad business. So in 2011 it stopped development of Android smartphones and dedicated Android 3.0 entirely to the launch of a new broadly licensed platform for Android tablets: Honeycomb. That ended up a spectacular failure that maintained a brilliant fireball of free fall disaster throughout 2011.

It was not only considered outrageous to hint in 2011 that Honeycomb might not be the Chosen One, but has ever since remained unspeakable to note that Google's tablet initiatives have become nearly as spectacular in their failures as Microsoft's. Android is winning! Because the game all along was to make little to no money amassing large inventories of products nobody really wants to buy, just like Apple did with Performas in the mid 1990s.

So much so that copious amounts data has been invented to support the idea that there are in fact tons of inventory of Android tablets being piled up in warehouses globally, and despite the fact that these piles aren't generating profit the way most commercial enterprises are expected to, their sheer size and mass are so grandiose that they essentially overwhelm any newsworthiness surrounding Apple's actual iPad business, its profitability and its functional ecosystem of actual apps.

Android is winning! Because the game all along was to make little to no money amassing large inventories of products nobody really wants to buy, just like Apple did with Performas in the mid 1990s.

Market research firms are gleefully knocking on doors to share the Good News that iPad market share of "tablet shipments" is down, particularly in China! This is such a relief to Google's Android partners who aren't making any money, and particularly to Google itself, because it distracts from the conspicuous bonfire of billions of its dollars related to an acquisition beginning with M and ending with otorola.

Google replicates Nexus smartphone failure with Nexus tablet fiasco

Google replicated its Nexus phone strategy with an Asus-made Nexus 7 tablet for 2012 that was so terrible that even Android's most devoted fans described it an an "embarrassment to Google."

One year later, the latest edition fixed some of its problems but introduced a crop of jittery, laggy, dysfunctional new ones.

Google didn't just copy Microsoft's broadly licensed platform fixation, its Zune fiasco, and its self-stabbing tablet missteps. It also did something else Microsoft does when it runs out of runway: it made a spectacularly expensive acquisition.

In late 2011, Google dropped an incredible $12.5 billion on Motorola Mobility, which the tech media celebrated as a way for Google to become as savvy as Apple in smartphones and tablets, as "protected" from patent attacks as any mature mobile device vendor, and emboldened in its Google TV initiatives thanks to Motorola's existing set top box business. Motorola's device savvy was actually so terrible that Google's executives described the company's 18 month product pipeline as something it needed to "drain" as if it were an impacted sewage pipe.

They were wrong across the board. Motorola's device savvy was actually so terrible that Google's executives described the company's 18 month product pipeline as something it needed to "drain" as if it were an impacted sewage pipe.

"We've inherited 18 months of pipeline that we actually have to drain right now, while we're actually building the next wave of innovation and product lines," Google's Chief Financial Officer Patrick Pichette told The Verge.

Motorola's patents have turned out to be so worthless that it's costing Google $14.5 million in additional damages for its role in pursing unscrupulous patent abuse tactics, on top of the $1.7 billion in operating losses Motorola has generated as a rotting albatross around the search giant's neck. And its set top box business was barely worth selling off as scrap.

At least we can agree that Microsoft and Google are trying

It's not common within the tech media to point out the clearly discernible absurdity of what Google and Microsoft are doing as they desperately seek to transition themselves from broadly licensed platform vendors to mobile device companies.

However, it goes without saying why they are trying to do so.

The age of broadly licensed platforms is over. The primary vendors of the world's broadly licensed platforms are all shoveling billions at efforts to turn themselves into an Apple, Inc.

The most interesting takeaway is that the entire world clearly shared a false delusion regarding broadly licensed platforms. That's important to recognize when considering the legitimacy of our remaining dogma. Perhaps we are wrong in other areas as well.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

182 Comments

You'll never convince the other side's sycophants that they are copying Apple's business model (vertical integration.) From stand alone retail stores, to iPhone form and function, to the iTunes Music Store, you name it, they have all come around to Apple's way of thinking but will NEVER admit it.

Another great piece, Daniel. Keep it up! And yes, I remember OS/2, Solaris, and NeXTSTEP. That was before computing became consumer-oriented. Microsoft never quite figured out the consumer market either. Microsoft's entire corporate culture is built around selling Window + Office licenses to businesses. They've done that relentlessly for decades, and they've been extremely successful at it. And now that success is holding them back. It's the only thing they know how to do well. None of Microsoft's core competencies translate to the consumer-oriented, post-PC, mobile world. Trillions of dollars out of Microsoft's reach. Day after day, day after day, We stuck, nor breath nor motion; As idle as a painted ship Upon a painted ocean. Water, water, every where, And all the boards did shrink; Water, water, every where, Nor any drop to drink. - Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1798

Strongly worded article. It's all true but the Fandroids are going to light up this comment section in a frenzied rage.

Begins? Microsoft has been doing since the Xbox and Zune. One of them failed miserably, and so have all their other devices since. Just because one thing works for one company doesn't mean it'll work for all others.

NeXT's original strategy was more like Apple's. it was only with OpenStep that they tried the MS approach. Interesting article. It isn't clear to me that the integrated approach is back in the driver's seat. Apple relies on the iPhone for the most part. Phone fashions change and a shift away from the iPhone would really damage the company. Philip