A report from the CBC has attacked Apple's policies and practices regarding repairs, taking the company to task for expensive in-store repairs, coercing customers to buy new products in some cases — but the publication shows a stunning lack of understanding of the scale of Apple's repair efforts, and leans too heavily on edge cases presented by a pair of respected "right to repair" proponents rather than actual observation.

Editor's note: The CBC has essentially reposted the video that they published two weeks ago, adding nothing new to the story. AppleInsider is reposting this editorial and examination of the CBC's original report, in its entirety.

The story from CBC's The National starts with an undercover sting on one Toronto Apple Store, with a "common problem" where the screen wasn't working properly. On inspection by one of the store's Geniuses, it was noted "there is a lot of liquid that's gotten on the inside," as water ingress indicator dots colored red confirming there to be water ingress.

The indicators led the Genius to advise the customer would "need to be looking at replacing quite a few components" due to the inferred damage. When pressed if it could be something else, the customer was advised that, "regardless of what the cause of it is," the liquid damage would have to be rectified as a priority, and that the store "can't do partial repairs when it's been damaged by something."

In terms of their options, the store employee advised it would cost a minimum of $1,200, with $600 and $500 quoted to replace the logic board and top case and $100 labor. If the display needs replacement, that would cost an extra $780.

When further pressed if there was a way to make it cheaper, the Genius advised the fee "is very close to the cost of buying a new computer. In terms of fixing it in the store? No."

The same MacBook Pro was taken to prominent YouTube repair personality and repair shop owner Louis Rossmann, who saw the same indicators in his inspection, but dismissed them as confirmation of immersion or liquid damage due to potentially being triggered by humidity. After discovering the display worked, but without a backlight, a bent pin in a display connector was found to be at fault, which was then pressed back in place as a repair within a few minutes.

Rossmann claims he could've provided a customer the repair for free as a short-term solution, one he believes would last for the remaining lifetime of the computer in the majority of cases. If the customer wanted a replacement cable as a longer-term solution, Rossmann estimates the cost to be between $75 and $150.

When queried how often customers turn up at his store after the Apple Store declines a repair or says it's too expensive to fix, Rossmann suggests it happens "somewhere between 10 and 30 times a day."

The report asked Apple to respond to this incident and allegations on the expensive repairs. A statement from Apple claims customers are best-served by "certified experts using genuine parts," and denies systematically overestimating the cost of repairs.

Repair outfit iFixit, known for its teardowns of Apple products and supply of support documents, parts, and tools was also featured in the video. Kyle Wiens, owner and spokesman for the national Right to Repair movement, advised it is "increasingly more challenging to get access to the information that you need, or for local shops to get the parts" for a repair, with the movement pushing for legislation to restore the ability for consumers to perform repairs.

"Apple's perspective is that it wants complete control over the device, from the moment that you buy it, all the way through to the end of life," asserts Wiens. "Right to Repair takes some of the control away from them, and puts it back into the hands of the owner. That's where for manufacturers to say 'we're making a product, putting it out in the world, and we'll control every aspect of what happens after the fact,' is complete lunacy."

Wiens goes on to show some of Apple's security practices to make it harder to repair products, including pentalobe screws and gluing batteries in place in an iPhone.

Repairing the Home button on an iOS device was previously considered an easy repair, the report claims, until Apple "reprogrammed its operating system to detect non-authorized Home buttons, and the phone would suddenly stop working." Without mentioning that the Home button also contains Touch ID and interfaces with Apple's Secure Enclave, Wiens likens it to putting aftermarket tires on a Tesla, then Tesla shipping a software update that would stop the car from working with those specific tires.

It "stems from a mentality that they are the center of the universe, and nobody is doing anything with their product," according to Wiens.

Apple is claimed to have sent legal threats to third parties who have published internal schematics and other documentation on its products, citing copyright infringement on the manuals, articles, and illustrations used for repairs. Threats of fines of up to $150,000 are noted, in a bid to get the shared information taken down.

The story then moves to the existence of Right to Repair legislation that would force Apple and others to provide manuals and other items, to aid in fixing problems with hardware. Campaigners believe that one state agreeing to introduce Right to Repair legislation would break the dam, with other states likely to follow suit in demanding manufacturers offer the resources to third parties.

Rossmann and iFixit have some legitimate points. CBC, on the other hand, does not.

Over-simplification of a complicated issue

The implication of the CBC video is that Apple takes the equipment that it gets back from customers and tosses it in a woodchipper, or feeds it to the Liam robot. This isn't the case, though.

Machines that are not captured by engineering for an evaluation of what went wrong are sent back to the depot for either repair and an ultimate destination of the refurbished device supply chain, or scavenging for parts which are then refurbished for other repairs. And yes, the refurbishment process uses people like Rossmann to make those repairs.

The iFixit organization is incredibly good at what they do, like partially dialing back the panic about the screen calibration software requirements for the T2-equipped MacBook Pro and iMac Pro — but they do have to make money somehow. The company makes a living by selling repair parts and tools. They shouldn't be begrudged this of course, and more than one AppleInsider staffer has tools that they purchased from the vendor, obtained parts for repairs from the company, or both.

Rossmann is also very talented at his work, and is incredibly successful. We have sent people emailing us about a difficult or expensive repair to his shop to get a second opinion. But, the CBC's implication that Apple should source repair technicians at each store with that level of talent is ludicrous, and if Apple did it, it would remove any economy of scale that the company holds by using a depot for component-level repair.

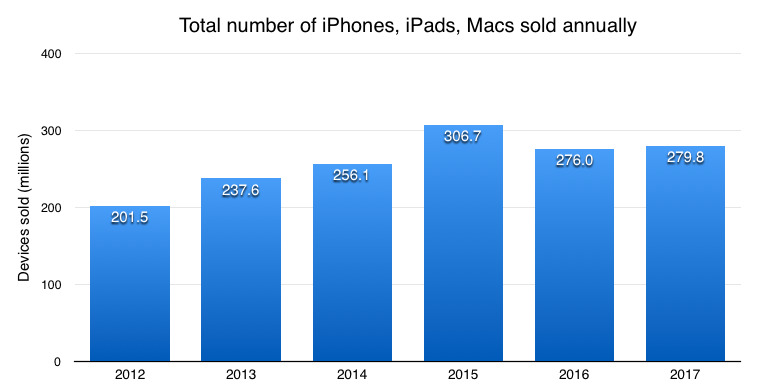

Service by the numbers

In the last five complete fiscal years, Apple has sold approximately 1.36 billion devices. If you assume that one in a hundred of all of those devices fail from reasons other than user-induced damage like a broken screen per annum, that leaves 13.6 million failures per year. That one in a hundred is less than half the industry standard of 2.5 percent for high-end gear after the initial 30-day infant failure period spanning through the first year of a device's life, and one fifth the failure rate after that year.

If you assume that there are 5000 authorized repair centers — about 10 times the amount of Apple Stores at present — that leaves a very conservatively low estimate of 27,000 devices per year per location that need to be serviced beyond a software reinstall. This doesn't include smashed screens, replacement batteries, or other user-induced damage which according to data collected by AppleInsider, is about triple what a shop sees for failures with no known cause, even before Apple's discounted battery replacement program was put into place.

Like it or not, Apple is a consumer electronics business. Board-level repairs at retail locations are far, far quicker for the company, require less-skilled workers at retail which can be paid less than a Rossmann-level technician, and all of this combined can get a functional machine back to a consumer faster.

As an exercise for the reader, hang out at an Apple store on any given Saturday near the Genius Bar evaluation table, and see how many customers demand instant repair or head-of-the-queue privileges because they have a deadline, Billy's birthday was Saturday and his pictures are in the machine, or data is stuck in the broken machine and it must come out for work.

For historical perspective, data collated by AppleInsider going back to nearly 2000 suggests that Apple's move in the Mac ecosystem to more sealed devices like the 2012 Retina MacBook Pro and later have cut failure percentages in half. More on that in the coming months as we continue to evaluate the data, though.

The battery, again

And, of course, the CBC video brings up the whole iPhone battery saga again, without discussing that a battery is a chemical process that depletes and loses efficiency over time. Batteries aren't eternal, and are a consumable — which Apple has always said, if perhaps not as vociferously as it should have.

We've talked about how this happens, why this happens, and Apple's response at some length before. So we won't be doing it here again.

Yes, Apple could have been more forthcoming with the iOS update that implemented the routines to prevent a device crash when voltage dropped below the critical threshold under load. However, AppleInsider still maintains that a device that doesn't crash but runs slower is still better than one you can't rely on in a pinch.

And, importantly, these devices with a properly functioning battery still move bits from register to register and perform operations just as quick as they did the day they were made.

Of course, we'd like the $29 battery replacement process to be carried forward in perpetuity, but it looks like it won't be.

Speaking of red herrings, why the CBC said that a video of a French tax protest with nationalist overtones was a protest about repairability isn't clear.

The problem with the "undercover" work

The device that the publication used had two problems — one, a series of tripped moisture sensors, and two, a bent pin on a connector. The sole Genius that CBC talked to followed the established procedure as set forth by Apple to examine the moisture sensors first.

Procedures exist in all industries for a reason. The technician didn't exhibit so-called "malicious compliance" nor try to extort extra money out of the "customer," but did his job the way he was trained to do, followed the procedure the way he was supposed to, and performed at the level of experience he was expected to have.

If every Apple store had Rossmann, or somebody with similar skill and experience, do all of the device examinations then the bent pin would have been found. But, there's still larger issues of time, and those 27000 devices per year that come in to each shop that need detailed troubleshooting.

Examinations like Rossmann performs take time. They can take a lot of time. A detailed examination and repair is more often than not a multiple man-hour process from start to finish. Which is better for the average consumer, one hour in and out of the store like can happen now, or a lengthy diagnosis, and repair?.

Any service center can reject any repair, for any reason — maybe you've heard us say this before. A botched repair, or damage induced by users tampering with equipment is specifically cited as a denial reason by Apple. This is done mostly for accountability reasons because the technician has no good way to tell what else has been damaged by the unusual failure mode.

Non-Apple Retail repair shops serve an important purpose

There are good, bad, Apple-authorized, and independent repair shops, and all the permutations of those four you can dream up. The key for the user is finding a shop that gives the user the best balance between affordability, repair turn-around, and quality.

The quality independent shops, like Rossmann's, will take jobs that Apple doesn't want to do, or won't do affordably — like the "undercover" CBC MacBook Pro. This is a good thing.

Apple's repair rules at retail, established by Apple corporate for uniformity, are there for a reason — including denials, and board-level repairs rather than component-level ones. Related to all this, regarding "right to repair" — Apple not making repairs easy by supplying parts or manuals to any given user isn't the same as blocking those repairs, which it is still not doing. And like we said, iFixit demonstrated that just last week.

Apple has a vested interest in guaranteeing quality parts are available for repair. It also has a vested interest in preventing low-quality parts from entering the third-party supply chain — if perhaps it enforces those rules far too vigorously for our taste.

Customers need Apple Stores to have Genius Bars. They also need venues like Rossman's shop, and iFixit. The two broad categories are not mutually incompatible, and do not focus on the same avenues for repair — nor should they.

And, it's probably an important point to remember that Apple's design and service choices make the devices fail less often, and the repair experience smoother for those that have dead iPhones or Macs, if perhaps more expensive. And, as a general rule, those customers don't have the same level of technical acumen that AppleInsider readers have, aren't looking to do the repairs themselves, and are fine with a device replacement.

And, these consumers outnumber "us" 20 to one or more.

Mike Wuerthele and Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele and Malcolm Owen

-xl-m.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

127 Comments

[quote]

Are you saying there are bad Apple-authorized repair shops?

Thanks for exposing the expose. Adding:

1) Apple's customer satisfaction is consistently at, or near, the top every year. Same for brand. The vast majority of customers are happy with Apple policies.

2) Batteries are inherently dangerous. Apple wisely protects consumers by making it hard to replace and expose consumers to physical safety risks.

3) As mentioned, the home key, tied to enclave, protects the users data. We don't want a thief to easily crack our phones and get our personal (and financial) data.

4) At least regarding iPhones, they remain in service longer than Android. That fact alone defeats the argument by CBC.

Bloody Canadians.