AirPods are emblematic of what makes today's Apple work. It's a competent technology product, but one that makes an emotional connection with you as you use it. And because they're designed to be used often and for extended periods of time, they keep associating themselves with your happiness derived from using them, ingratiating themselves as trusted devices that recommend that you buy more gear from Apple in the future.

Hi-tech, with feeling

Apple is known for advancing technology in huge leaps: the original Macintosh, iPod, iPhone, and other iconic new products delivered a set of functional capabilities that were well beyond what was currently available. Each of these new products gave Apple a strong position in an emerging industry, largely leveraging new technology.

However— and far more importantly— Apple has also learned how to bypass technological advances with emotional satisfaction. This is key to understanding why Apple's premium products seem to be impervious to external commodity and disruption, two factors that are asserted almost daily as the reasons why Apple is really close to losing everything, despite having survived for four decades as the world's oldest and most consistently relevant technology enterprise, one that is now leading in its share of profitability in virtually every industry it participates in.

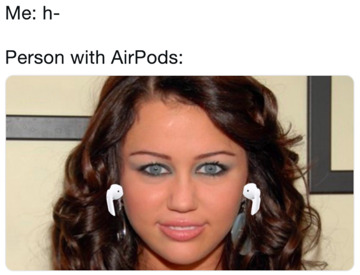

AirPods are a product that meekly crept into our consciousness as an accessory, then surprised pundits by outselling a variety of more technically advanced headphones. At the same time, the wireless earbuds established themselves as an authentic symbol of affluence and freedom. Apple didn't have to advertise that AirPods "make you look rich" or "render you casually oblivious to outsiders" or "establish you in a privileged group." Popular memes created those iconic ideas on their own, initially as criticisms or jokes rooted in reality.

Early AirPod memes made light of their appearance. The one above, which keeps circulating on social media, appropriated my AppleInsider product review selfie to compare wearing them to the scene from "There's Something about Mary." I had intended only to show off the look of wearing AirPods, and we didn't have a budget for hiring a face model. Instead, I became this image of a person casually-busy just with listening to music, and probably unconcerned about the potential for losing one of my wireless buds because I can probably afford to buy another pair. The conspicuous consumption image of self-contented affluence from wearing AirPods came to be known as AirPod Flexing.

From social media profiles to dating apps, AirPods are getting flexed everywhere. And it's not just a passing fad. Apple made listening to music wirelessly effortless, enjoyable, and mainstream affordable. In a market where sales of wireless earbuds are not protected by a monopoly or a specific patent, Apple's ability to utterly dominate the "hearables" category provides some insight into the company's innovation and competence— particularly in contrast to what's around it. Note there were many attempts at Bluetooth wireless headphones before Apple arrived— and Google, Microsoft, Samsung, and Amazon have all made moves to copy them since.

Skating to where the headphone wires were

AirPods were released at the end of 2016, a year where the primary story about Apple was that it had run out ideas and that its next iPhone would be nothing new— it wasn't even getting a radical new change to its case! CNET and the Wall Street Journal were rolling out stories that begged readers to consider Samsung's Galaxy S7 instead as the year's "all-around phone to beat." It had an "innovative" Edge screen that bent its OLED display around the front corner of the display.

The tech media establishment was exhausted from a busy year of reporting that Apple was "lacking innovation." There had been so many complaints that year that Apple was purely out of ideas and that absolutely nothing new was going to occur in 2016 that I wrote the forward-looking rebuttal, "Actually, there is something new about Apple's upcoming iPhone 7."

The article noted among other points that "Apple is also expected to remove the legacy audio jack on new models and focus attention instead on wireless Bluetooth audio or wired Lightning audio, both of which offer major, significant benefits over today's analog plug, ranging from tangle-free convenience to superior sound reproduction."

That was an unpopular idea to express at the time, when Nilay Patel at The Verge was calling Apple's expected removal of the headphone jack "user-hostile and stupid," and imploring Apple in a subheading to "have some dignity." Rather than having the ability to fathom the potential for wireless audio in the future, all he could see what that the shift might offer Apple a significant advantage in old fashioned wired headphones moving to Lightning. He raged that "making Android and iPhone headphones incompatible is so incredibly arrogant and stupid" without even giving the idea of Bluetooth much thought, despite working for a tech magazine.

AirPods mocked by the authors of Bendgate

Then AirPods dropped. At $160, the new devices were not cheap but were more affordable than Samsung's Gear Iconix ($199) or the Jabra Elite Sport ($239). And more than just iPhone 7 wireless earbuds, the new devices enabled easy pairing across devices, working even from your Apple Watch or Mac. You can access Siri voice requests to your phone, and you could even pair them with Androids, although they don't support AirPods' advanced codecs that enable longer battery life and better sound.

Like Patel at the Verge, tech writers around the globe reviled AirPods as looking dumb and being too easy to lose, and so much worse than beloved analog wired headphones. "The beauty of the headphone cable is just like the beauty of a tampon string: it is there to help you keep track of a very important item," wrote Julia Carrie Wong in the UK's The Guardian.

Non-commercial memes about AirPods sloppily added oversized graphics to an image, or referred to the product at EarPods, or in various other ways screwed up in a way that felt authentic. A generation of users decided that AirPods were nice to have, made you feel good using them, and were at worst potentially distracting. The appeal and recognition of AirPods went through the roof. And because these messages were audience generated, rather than being marketing, they were far more effective at shifting behavior than any commercial surveillance advertising that might slip an ad for a Pixel right in front of a millennial that orders Amazon products using Gmail and is tracked to a specific food delivery app on his phone.

In March, Apple's chief executive Tim Cook graphically announced the release of the new AirPods with a Twitter meme-homage of his own (below). And like the memes of millennials, he borrowed from and augmented an earlier Portrait Mode image that had announced the iPad mini with Apple Pencil support in an iPhone XS-captured photo with the background bokeh of Apple Park's drought tolerant grass. Very millennial, and yet still wasn't promoted as an ad, but rather was organically spread around by followers.

— Tim Cook (@tim_cook) March 20, 2019

AirPods' appeal of attainable affluence and freedom

Wearing AirPods, they fade away invisibly, with no cords to get in the way or catch on things. They add a soundtrack to your life. And in the same way that the Internet-enabled users to look up and read about whatever they were personally interested in rather than being queued up content by a TV channel, AirPods forward the model of Apple Music, Podcasts, Spotify, and iTunes to let users listen to whatever they like, rather than following a broadcast or being forced to engage in public conversations they don't want to have.

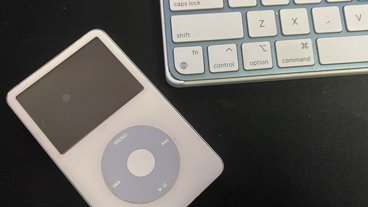

Particularly when paired with Apple Watch, AirPods deliver a supercharged version of the experience of the original iPod. And because users can take them virtually everywhere, AirPods are commonly associating themselves with users' happiest moments. By associating joy, relaxation, the high of a fitness workout, or simply an escape from a transit commute with wearing AirPods, the device is becoming a familiar, loved product.

That feeling reminded me of the iPod. I didn't buy my first until the third generation in 2003, even though I'd been working at an Apple reseller at the time. I had been super depressed, struggling through life in a way that increasingly seemed bleak and joyless. I couldn't identify anything that was wrong that I could change, and it felt like things were just getting worse. I was getting used to being unable to be happy, and increasingly isolated myself socially, making things worse.

When I plugged in my new iPod and started listening, something unexpected happened. I was transported back to being 17 again, and listening to my first CDs on a Sony Discman that I'd paid some extravagant amount of money to own back in the day. It took me to another world and let me feel happy. Now, this iPod 3 was doing that. And today, AirPods do that. They target the emotional experience of music and perform an exceptional job of orchestrating whatever I want to listen to— or even suggest things if I'm too lost to know what I want to hear.

Sometimes I still get super depressed for reasons I don't always even understand. But here we have this accessible technology that can arrest your thoughts and envelop you in an invisible cocoon of sound that makes you want to dance along or at least walk faster. And it recommends other things you might want to listen to: podcast conversations, centering meditations, or all the colors of music from serious and dramatic to playful and catchy. AirPods deliver a powerfully emotional experience.

The emotional computer

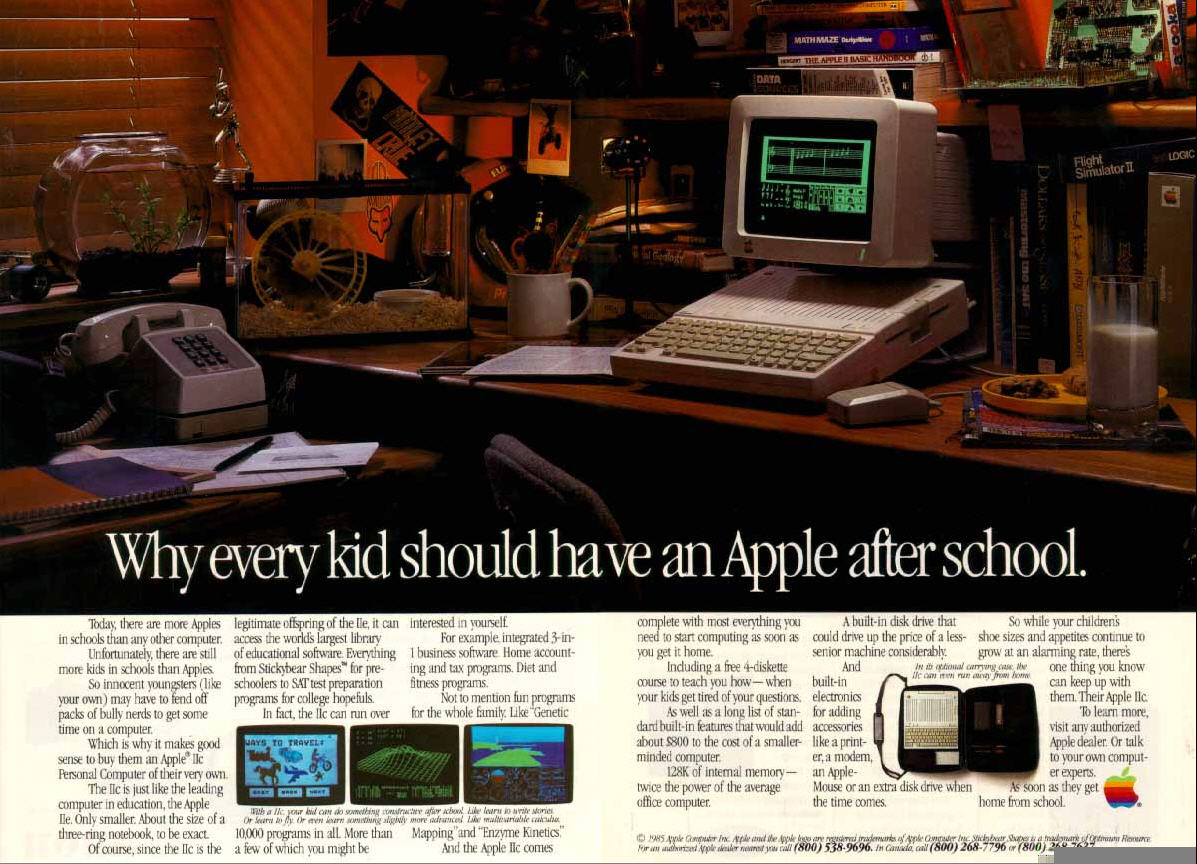

Advertisers spend tremendous amounts of resources in attempts to get us to think about their products. Early ads for computers sought to tap into a rational, intellectual curiosity for owning machines with a practical, valuable purpose. Apple's early focus on education suggested that video games barely existed, when in reality games were playing a significant role in attracting buyers to computing.

In the 90s, Apple increasingly lost its emotional appeal by relentlessly focusing on 'the power to be your best' and the productivity that might spring from using its Newton PDAs. There wasn't a lot of fun to be had.

When Steve Jobs introduced iMac in 1998, he appealed to esthetics that had been getting little attention at all in PCs, along with the games that had. The new iMac was designed to be fun and friendly to use.

When Jobs introduced iPod in 2001, he associated enjoying music with happiness. He previewed marketing portraying silhouettes dancing with white earbuds that felt freeing— there were 1,000 songs in your pocket and all you had to do was push buttons and dial a wheel to listen to anything you wanted to hear. The technology Apple delivered was good, but what made it figuratively sing was that it didn't just do a utilitarian task. It served the purpose of making users happy.

Microsoft's PlaysForSure MP3 player licensees and various other competitors rushed devices to market that could play video, or could load SD Cards or added some other feature. But those technical firsts weren't joy-inducing. They were part of a frustrating package of complexity and busywork that required that the user configure devices and learn something about audio codecs and DRM licensing rules. Being technically advanced didn't increase their emotional value. It decreased it.

Apple's efforts to create products that made users happy carried along into iPhone, which introduced effortless Internet access, enhanced messaging, maps, casual gaming, and music and video playback that all worked well. Apple developed an entirely new framework to animate the iPhone user interface in pleasing ways to reduce frustration and clarify navigation. The company spent significant time creating an experience intended to make users happy.

Rivals were making phones that were better at placing phone calls reliably, or at typing on small keyboards more efficiently, or in connecting to enterprise systems conveniently. Apple's iPhone focused on being delightful. That emotional link— resources that were devoted to making iPhone enjoyable, rather than just functional or technologically advanced— enabled Apple to rapidly displace an entire existing industry.

Today, Apple's only serious competition in phones is a free platform that struggles to deliver technological gimmickry — curved screens, folding displays, cameras that can take photos in the dark. None of those things resonate emotionally. None of the reviewers capturing pictures of their dimly lit junk drawer with their amazing darkroom camera feature experienced any joy.

When you take a flattering portrait of a friend with iOS' Portrait Lighting you do. When you control the volume of your AirPods with the Digital Crown on your Apple Watch, you might also feel good. And when you hear that louder version of the song that makes you smile, or pump your fist, or that reminds you of being in love, it makes you happy.

And there are few things that make people willing to pay a premium more than a product that consistently delivers joy when you use it.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

28 Comments

I love your insights. But split a hair on 'premium' While Apple products have a premium appeal, they're usually priced at or below, if one just considers price net of residual or net of trade-in. Caveat: When competing with clones, there will always be clearance priced models or new entrants with deep discounts, BOGO offers.

When pixel was first launched it was to the penny (and performance wise) a near perfect match to iPhone. I did a comp to Sony's year late "air" version of a PC laptop, a flop that was priced slightly above MBA.

If one looks at truly Veblen goods, the best example is the roller luggage design for carry-on. They range from about $200 (not so good but OK) to about $1,000 for top of the line, and to veblen, Guggi, etc to $2500.

If you look at gross margins, Apple's are average. Apple's secret is their combined R&D and SG&A %'s, Apple's are much lower than comparison in tech or consumer products. That's why Apple is so profitable.

Great piece, Dan. Cheers!

That is how I feel about the latest iPad Pro 12.9”. Useful, functional and a fun device. The best of a computer and tablet enclosed in one superlative device.

An integrated stylus is one of those amazing to have features.

and when Siri fails to recognize my command again and sidetracks to something completely different and the text corrections fails horribly (or embarrassingly) and a modal popup blocks my input ... that certainly makes my emotions play up