The history of personal computing is often told in terms of operating systems: the dramatic battle between IBM's DOS PC vs Apple's Macintosh; the emergence of fiefdoms of promising independents such as Amiga OS, NeXTSTEP and BeOS; and ultimately the crushing destruction of any PC OS competition under the homogenous, global and permanent rule of Microsoft's Windows platform. But these stories often resulted in inaccurate conclusions, because the OS platform wasn't the only important factor in picking winners and losers.

Microsoft conquers the PC world, end of story

The dominance of Windows in PCs has long been celebrated by media pundits seeking to associate themselves with success by predicting the comfortable continuation of the status quo. But that confidence also blinded them to the reality that too much success tends to result in complacency.

While it was obvious— at least in hindsight— that the Macintosh's solid decade of essentially owning the graphic desktop from 1984-1994 ended because Apple was unable to outpace the much greater sales of its competitors all being armed by Windows, few seemed to grasp the possibility that a decade later, Microsoft could also begin falling behind as Apple began leveraging its own higher volume sales of mobile devices, starting with just iPod and then adding tens of millions of iPhone and iPad units.

Nearly everyone in the PC industry imagined that when history repeated, it would be Android that played the role of Windows as the single, homogenous OS that ruled a new class of even more personal computing devices. But while Android device shipments have indeed outnumbered Apple's sales, they haven't pushed Apple out of business or sidelined its ability to move into new markets. Understanding why is worth millions of dollars.

The unthreatening rise of Windows

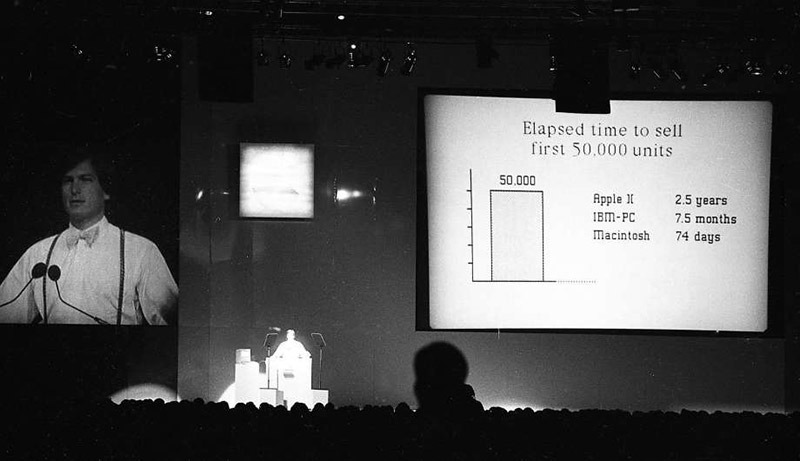

Back at the end of 1995, most Windows PCs weren't even remotely capable of directly competing with Apple's most profitable Power Mac towers and PowerBook notebooks; in fact, many Apple fans dismissed Windows 95 as being "Mac '89," hopelessly unsophisticated, far behind, and completely unable to directly compare with Apple's mature product that was already pioneering desktop video editing at an era where PCs were struggling to playback audio consistently.

Apple itself didn't seem to take Windows too seriously. It had comfortably owned graphical computing for a decade and was expecting to continue to branch out into application software with Claris, QuickTime, and HyperCard; futuristic new form factors such as Newton and eMate; and the emerging market for workstations and servers with its A/UX and partnerships with IBM. IBM had invented the DOS PC and even it didn't take Windows too seriously.

Windows 95 PCs did not take away Apple's core markets immediately. Instead, they began opening up vast new markets for casual PC users who wanted to play games and dial-up America Online and gain access to the emerging commercial Internet. Microsoft also pushed Windows into the enterprise. Windows PCs were arriving with gaming features and business software at prices that Apple wasn't prepared to match.

An established base drives Microsoft forward

It was only after establishing an installed base of Windows users that Microsoft would begin bleeding Apple's higher-end Mac sales to death. Microsoft brought its Office software— which had originated and had only been popular on Macs— to Windows, creating a familiar PC experience for Mac users. It subsequently introduced its own handheld devices, workstations, and branched out into servers, the very markets Apple imagined it could move into.

Apple's growth in Mac sales was held in place while Microsoft expanded Windows, Office, and Server into $10 billion legs of its operational stool, leveraging the support of the world's PC makers all licensing Windows. The rise of Windows had an even more destructive impact on other OS competitors, from PC giant IBM's OS/2 to the various UNIX variants that had been powering workstations, to smaller niche platforms like Amiga OS, which had solidly established itself in video editing.

The dramatic rise of Windows created a lasting impact on the minds of industry observers. From their writing, it's clear that they almost unanimously believe that the pivotal shift in computing history they watched happen in the mid-90s could never occur again. Microsoft would rule the world forever, certainly for much longer than Apple had managed to retain its control over graphical computing with the Mac back in the 80s.

The revolution would not be televised

But that didn't turn out to be true. Apple somehow regained market power and began selling new volumes of Macs, assisted by the support of new sales of mobile devices. That dramatic shift, which resulted in Apple completely turning the tables on Microsoft, began in less than a decade after Windows 95.

In the early 2000s, Apple's iPod made an appearance that many discounted as irrelevant. Just as Windows 95 couldn't immediately compete in Apple's core markets, iPod similarly wasn't competing with Microsoft's bread and butter Windows PCs; instead, it was opening up a new market for very personal mobile devices, with media features and prices Microsoft and its licensees were unprepared to match.

By 2004 iPod had trampled Microsoft's Windows Media Player and PlaysForSure "Portable Media Player" platforms. Three years later iPhone similarly crushed global Windows Mobile handsets almost immediately out of the gate. Three years after that, the iPad not only crushed the emergence of Windows Tablet PCs and netbooks but also destroyed any future growth of PC sales.

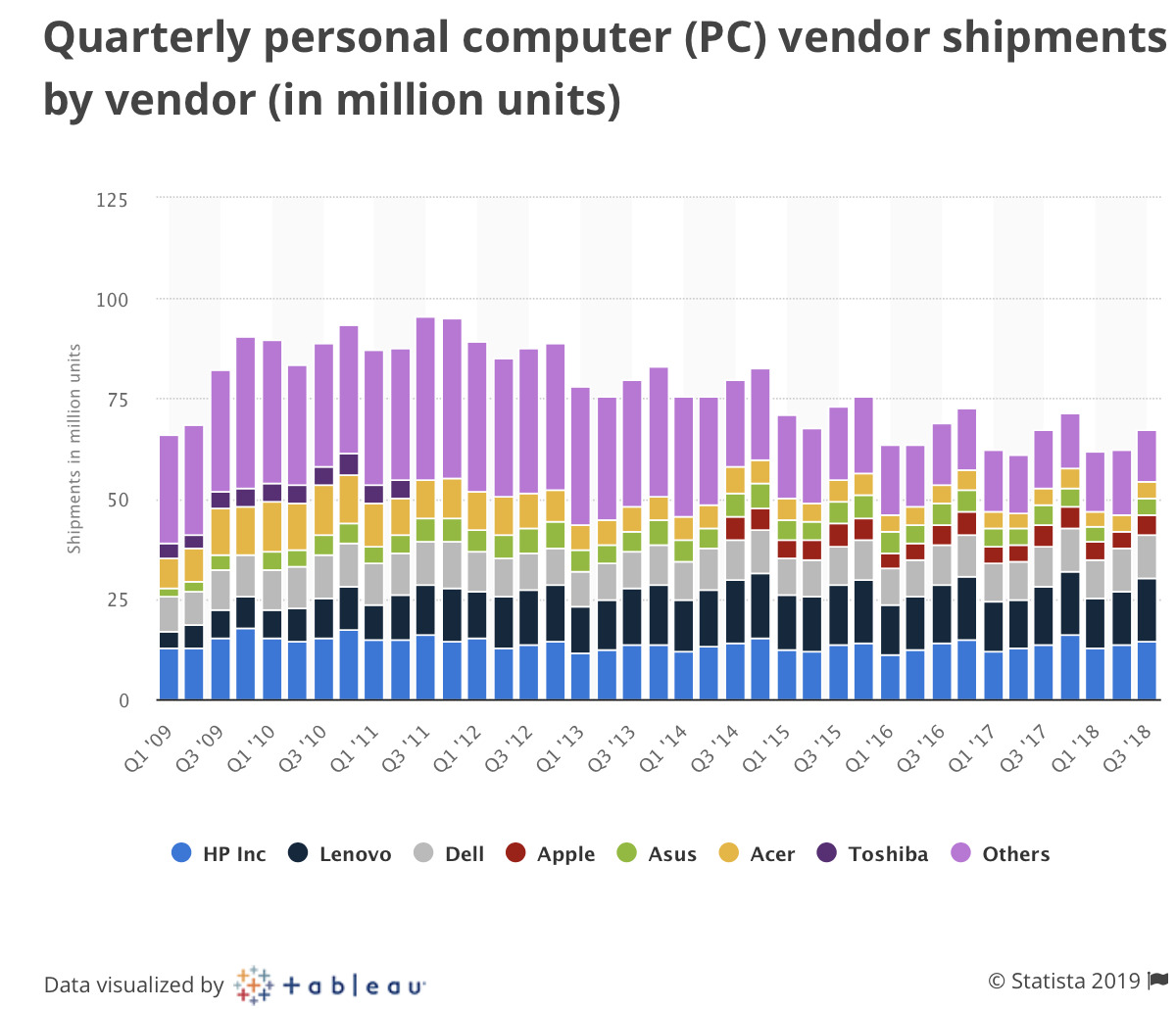

Since iPad appeared in 2010, Windows PCs sales volumes have been held in place while Apple has managed to increase both its iPad and Mac sales, even at premium prices compared to most other PC vendors. And at the same time, the iPhone turned into such a vast business that it made the iPad and Mac look relatively small.

PC makers saw the impact of iPad

The narrative that Microsoft's one licensed OS would prevent alternative competition and dominate the industry forever was simply wrong. This idea was so cherished by pundits that some of them even today don't seem to grasp what has occurred. But Apple's successful competitive moves in mobile devices destroyed the faith of Microsoft's licensees in real-time— essentially within the same year that Apple launched iPad.

Just months after appearing on stage with Microsoft to launch Slate PC, HP abandoned its new Windows Tablet PC model to pursue its webOS tablet with the purchase of Palm. That same year, Microsoft's leading "OMPC" Tablet PC partner Samsung dropped its Windows-based Q1 to adopt an Android tablet strategy. Dell, along with virtually every other PC maker, also began shipping Android tablets to defend against iPad.

Yet rather than accurately appreciating what Apple was accomplishing, media pundits described the rise of iPad as a sort of temporary aberration. If Windows was losing any ground at all, this could only possibly occur at the hands of another broadly-licensed OS platform. It couldn't possibly be Apple killing Windows; it must be Google's Android.

Nearly everyone in the tech media imagined the future of iOS and Android playing out like the history of Mac vs. PC: Apple was going to sidelined by all the world's electronics makers jointly working with Google to deliver a more open mobile platform, could innovate more rapidly, and could beat Apple's prices.

The market reality obscured by Strategy Analytics, IDC & Gartner

Yet Android was unable to deliver the same sort of crushing defeat to iPad as Windows 95 had to the Macintosh. This reality was obscured by fake data invented by media research groups, such as Strategy Analytics' false portrayal of Android tablets immediately gobbling up 20% of the iPad's market just in the last three months of 2010.

IDC later insisted that iPad was being vastly outnumbered by huge volumes of Android tablets it assumed were being built and sold, simply by counting the production of components that could be used to build such tablets. Those imagined Android tablets curiously never showed up in web statistics.

Gartner and other groups also desperately tried to hide any direct comparison of iPad and PC sales by calling iPad a "media tablet" that wasn't in the same market as "real computers" running Windows, despite the fact that iPad was clearly replacing not only home PC sales, but also finding new roles in the corporate enterprise, in retail sales, in cockpits, and in entirely new roles for mobile workers.

The appearance of a new Disruptive technology— one that could compete with the established status quo not by feature parity but by offering a simpler, cheaper and more effective replacement that better served the needs of buyers— should be the most valuable insight that market research groups can identify and prove with their data.

Yet rather than calling attention to the threat posed by iPad, its relevance was instead quite purposely hidden by market research groups, making it very clear that their public data was free for a reason: it wasn't shared to provide free facts. It was carefully crafted and framed to support the initiatives of the companies who were paying it to support them.

My email inbox is absolutely overwhelmed by unsolicited offers to provide free statements from a company CEO or market research group sharing insight and carefully crafted data supposedly proving an important trend. I don't even write up their ideas, so imagine how much free "content" is streamed to the "journalists" who do rely on outside whispers to guide what they write.

When everyone writes up the same headline about a particular bit of data, you can be assured it was the result of some marketing group forwarding it out. You can be reasonably assured that if somebody is spending their time to disseminate facts for free, it's most likely a contradiction of reality.

None of these research groups were spending their time announcing to the public that Apple was going to march past Windows and Android to become the most valuable, powerful and important company in electronics. That means they either didn't know that was happening or didn't want anyone else to know it.

Death of the single, broadly licensed OS platform

Google's Android licensees have certainly outnumbered the sales of Apple's iPhone— particularly if you count all of the Android Open Source Project devices and Android forks that are used to deliver Android-like platforms, without Google's control. But unlike the rise of Windows in the mid-90s, the sheer number of Android devices being sold globally have not had the same effect on Apple's sales or its ability to enter new markets.

Sales of iOS devices weren't held in check by Androids. Instead, Apple's sales kept growing rapidly and profitably in parallel with Android handsets and tablets. Unit sales of iPhones only began to plateau after the global market for all smartphones grew saturated. Unit sales of iPad hit a high in 2014 and then fell back to a lower volume level, but that occurred only as everyone else's tablets crashed entirely and never recovered.

Rather than iOS being locked in a dramatic war with Android in a zero-sum game, the results of both platforms seem to be almost unrelated, as if they are playing entirely different games. That's because they largely are.

There is not one game

Apple has flourished in a premium niche, selling iPhones that are priced between $400 and $1500, at an average selling price currently north of $750. Android phones are largely priced below $400, with an average selling price of around $250. Rather than killing the iPhone, Google's strategy of driving waves of cheap phones has only shipwrecked the market for premium Androids.

Apple has been extremely successful in launching new tiers ultra-premium iPhones at comparatively high prices and selling them in mass-market volumes. The real victim of Android licensees' high volumes of shipments at low prices is the premium offerings of those same companies.

How many people will buy a $1500 Samsung Galaxy S10 when a Galaxy A works effectively the same at $300? Samsung itself has clearly articulated to its investors that there simply isn't much remaining opportunity at the high-end, causing it to realign its priorities to instead focus on ~$300 middle-tier products like the Galaxy A, which are cheaper to develop and build and can find high volumes of buyers.

Samsung's premium Galaxy S and Note phone sales were once expected to outpace Apple's premium sales. But premium Galaxy sales peaked in 2014 and never recovered. Instead, Apple effectively stole away a large chunk of Samsung's premium "phablet" market by offering its own larger iPhones.

Winning the wrong game is losing

Even Google itself has been completely stymied in its efforts to ship any significant volumes of its Pixel phones, a device it has worked hard to position as the nicest Android phone with the best and smartest new services Google invents. But Pixel is really competing against $300 Androids for attention, not similarly priced iPhones. Market data has consistently established that there is very little movement between iOS and Android by users.

Google's inability to sell a premium Pixel and Samsung's inability to sell a critical mass of premium-tier Galaxy S phones have also been mirrored across the Android world by startups seeking to launch a new premium Android, from the security-hardened Blackphone to the Essential project by Android's founder Andy Rubin, who took the millions Google paid him off to leave the company and ended up with a flop, killed by his cheap volume strategy.

In tablets, the "Android is winning" story is even worse. Google itself has backed out of tablets entirely. All of the PC tablet makers who replaced Windows with Android failed to see any difference in their results. Samsung achieved some success in phones but hasn't really made any money from tablets.

In wearables and TVs, Android is not only failing to establish itself but is facing direct revolt from its licensees. Those partners are not seeking to find another new broadly-licensed platform to rescue them from Android. They're building their own platforms.

In a remarkable twist, LG acquired the remains of webOS from HP to use the platform for its future Smart TVs after its Google TV partnership flopped as badly as HP's Slate PC had three years prior. Samsung has similarly pursued its Tizen OS to develop wearables and TVs after Google's Android Wear bombed. Outside of Sony, the most successful Smart TV vendors are all pursuing proprietary OS platforms in the model of Apple, rather than looking for another consortium to join.

Pretty clearly, the media narrative that broadly licensed software platforms were the primary driver of economies of scale— grounded on the success of Windows PCs between 1995 and 2005— turned out to be incorrect in media players, phones, tablets, TVs and wearables. Instead, another factor played a huge role in charting out the future of personal computing and "smart" devices, and this will continue. The next segment will take a look at what this was.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

65 Comments

I could tell who the author of this atricle was just by reading the title.

Maybe I need to spend less time in the "computer world".

Nothing like a good refresher course in PC history like one from DED.

“

Absolutely the best line in the article.

Thanks for setting the record straight.

Windows has proven long ago that the main dimension for product differentiation in computing devices is the OS not hardware. Meaning a mass market for 'high end' Windows machines can never be sustained as long as dirt-cheap good-enough Windows machines are available. Even people who can afford it will pick the low cost machines because the pace of technological change is so fast, who would want to spend a lot of money on a machine that will be outdated in 3 years?

The seminal case is Northgate Computers who started selling DOS-Windows machines using high end components and materials in 1987 and was filing for Chapter 11 by 1994. Steve Jobs knew this so the one of the first things he did when he regained control of Apple was to kill Apple's licensing program. The idea that the clones would sell to the low end Mac market while Apple reserved the high end of the market for itself was just sheer stupidity. High end Macs will not sell as long as dirt-cheap clones are available.

Fast forward to Google and Android. When it first came out, I predicted that the same dynamic will apply and there will be no sustainable market for high-end Android phones. I also predicted that Android will be the phone OS of choice in the third world. 2 out of 2. Not that I was going out on a limb with those predictions.

The amazing thing is that Google thought that Android phones would not repeat the pattern shown by Windows computers. So much for hiring Ivy League economics professors to advise them.