Now that more details about Apple Silicon have been revealed, it's clear that even the giddiest expectations fell far short of Apple's real ambitions in building its System-on-a-Chip brains for a new generation of Macs.

Not the iPad Mac

For several years now, long-term Mac fans have fretted that their beloved, 40-something-year-old graphical computing platform was being sidelined as all of Apple's attention was being focused on the youthful new future of iPads. Apple's CEO Tim Cook has frequently expressed his affinity for the mobility of iPad, causing some to worry he might someday abandon the Mac as a complex relic of the past.

Apple has promoted the iPad as an effortless to use, ultra-light, super thin, long-life computing experience for mainstream audiences. Over the last ten years, the iPad burst onto the scene and radically shifted how educators teach, how salespeople market, how the enterprise deploys digital tools for its workers, and how individuals relax with technology at home.

While iPad has ballooned into a huge new computing platform of hundreds of millions of users, it hasn't replaced the venerable Mac. Rather than being "cannibalized" by iPads the way that the markets for netbooks and basic PCs were, Mac sales have grown alongside iPads— and not by accident.

Clouds of insistence from analysts and columnists claiming that Apple would— or even should— let go of Mac sales to concentrate on iPads turned out to be ill-informed noise. The idea that Apple needed to merge or integrate its two computing platforms into a "refrigerator toaster" hybrid also proved to be wrong.

Instead, Apple has continued to maintain macOS and iPadOS as separate platforms differentiated by their user interface and the core tasks they perform for different audiences. At the same time, the company has increasingly brought new technologies from one product to the other, making adjustments as needed to fit each's unique characteristics.

When Apple shipped its first Developer Transition Kit at WWDC, some were surprised that it was effectively a Mac mini enclosure with the internals of an iPad. That again reinforced fears that the future of the Mac might be just a big iPad— similar to how the original iPad ten years ago was dismissed as "just a big iPod touch."

However, that's not what Apple will be shipping as its new M1-based Mac mini later this month. Instead, the machine boasts an entirely new chip explicitly optimized for the Mac. And it's more than just a chip. As a "System on a Chip," Apple's new M1 leverages the power of shrinking down and tightly integrating various components into a single part. That's the real secret that has enabled semiconductors to transform technology and advance the future of computing— the often forgotten partner of the software running above it.

The Big Sur prize

On top of building its silicon, Apple is also unique in the industry as its own software developer. A lot of computing companies once did both— DEC Alpha; SGI and MIPS; IBM and POWER; Sun Sparc and Solaris. But for many years, most PCs shifted to the duopoly of Intel and Microsoft. Developing custom silicon or an original OS software platform just seemed like too much work.

Apple's new M1 is specifically optimized for macOS Big Sur. While the chip enables Macs to natively run apps developed for iOS and iPadOS for the first time, Big Sur also includes Apple's Rosetta 2 technology for translating existing Intel apps to run seamlessly as well— in some cases even faster than they would run on Intel chips.

Moving an existing platform to a new processor architecture is a lot of work, fraught with problems. Microsoft has been struggling to get its Windows platform to run effectively on ARM chips since the total failure of Windows RT back in 2012, despite setting expectations for compatibility quite low. Sony experienced some headaches with its new generations of PlayStation video game consoles moving from MIPS to PowerPC to AMD, even with limited expectations of backwards compatibility.

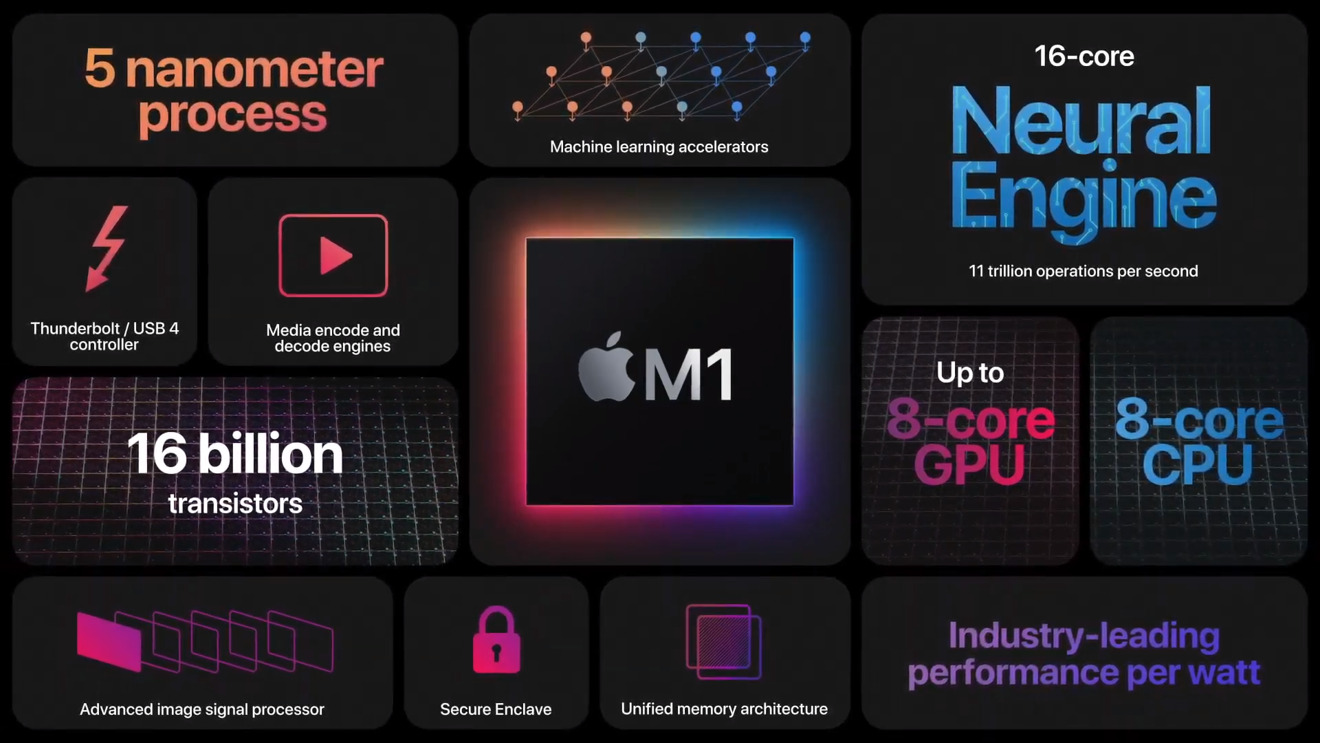

Today, Apple has to deliver a seamless, effortless transition that runs effectively all existing Mac apps on an entirely new CPU architecture. Apple isn't just shifting from Intel to new CPU cores — it's also moving the Mac to its own Apple GPU architecture for the first time, while also debuting its Neural Engine on the Mac along with custom ML acceleration blocks, plus a variety of other specialized hardware controllers, codecs, a new image signal processor, a new memory architecture, and a freshly custom-developed Thunderbolt controller supporting the new USB 4 specification.

Reports from Reuters to the Wall Street Journal have tried to suggest that all Apple is doing is moving from Intel chips to a "design from ARM Holdings," which is entirely false. The new M1 Macs are the most uniquely custom-developed Macs ever, with altogether new blocks of logic all crammed into the most advanced development node available anywhere. ARM doesn't sell an M1.

TSMC's state of the art 5nm process for manufacturing ultra-dense semiconductor designs is newly enabling Apple to shrink down an entirely new and incredibly advanced Macintosh logic board into a single chip. This is orders of magnitudes far more sophisticated than Microsoft compiling Windows to run on a Qualcomm 8cx chip "customized" only in the sense of running at a different clock speed.

The last time we saw an entirely new PC this novel and uniquely advanced compared to the status quo was perhaps Steve Jobs' NeXT Computer back in 1988, which similarly incorporated custom logic chips to handle new kinds of processing that had not been done before in a desktop computer.

Apple's iOS Silicon

All of the new technology on display in the new M1 chip is not, however, merely a version 1.0. Apple has spent the last dozen years perfecting and enhancing its increasingly bespoke silicon designs, including new processing engines, new microcontrollers, and novel security features. Across a decade of iPhone and iPad releases, the company has relentlessly advanced the state of the art within its SoCs while critics continually credited this work to "ARM," most recently suggesting that Nvidia had somehow snatched up this asset with its acquisition of ARM Holdings.

Nothing could be further from the truth. No other ARM licensee, or manufacturer using chips from some other ARM chip maker, has yet matched the sophistication and pace of Apple's silicon engineering. And it hasn't been for want of trying. Samsung dumped massive investments into an effort to build its own M series chips before giving up.

Furthermore, Huawei and other Chinese makers have manufactured ARM reference designs under their own brand names, without achieving Apple's results. Nvidia desperately tried to beat Apple with its Tegra chips before throwing in the towel in smartphones. Qualcomm has been embarrassed by its fall from mobile chip leader to merely a runner up by Apple ever since it was caught flat-footed by the 64-bit A7 back in 2013.

Intel once spent billions subsidizing Android licensees to produce tablets with its mobile x86 Atom chips before giving up on mobile. And now, Apple is taking its mobile expertise developed to power iOS devices and using it to drive its notebook and desktop Macs, starting with the MacBook Air, 13 inch MacBook Pro, and Mac mini. The company expects to complete a transition over the next two years. That would be hard to believe from anyone else, certainly after Microsoft's eight-year struggle to make little progress with Windows for ARM.

But for the company that pulled off a transition to PowerPC processors while crippled with beleaguerment in the 1990s, then rapidly transitioning to Intel chips in 2006 while in parallel launching iPhone, despite still be regarded dismissively by the industry in the mid-2000s, using its new tier of custom silicon to build a new generation of Macs just looks too easy for the two trillion dollar company that now sets standards and defines the products that the rest of the industry meekly seeks to copy.

As I outlined before the M1 announcement, Apple's move to its own SoCs isn't just a chip migration. It's a radical rethinking of desktop PCs that leverages massive amounts of engineering work already completed to deliver iPhones and the light and thin iPad platform, to make them ultra-responsive, radically mobile, and blur the line between hardware and software.

M1 brings ML acceleration, NSP, and a unified graphics architecture to the Mac desktop. And, notably, it optimizes macOS to take advantage of all these technologies from iOS while also freshly optimizing Apple's iOS SoC silicon to serve Mac tasks, most notably Xcode development, but also Metal-enhanced gaming, hardware-accelerated video editing, iPhone-class digital imaging, and incredibly fast new custom storage and memory architectures. It also brings advances in security, lightning-fast wake from sleep, and dramatically increased battery life— all while also being faster than comparable Intel chips.

Let AppleInsider know what you'd like to know about Apple's new series of M1 Macs.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

33 Comments

It will be interesting to see what kind of bill of material reduction Apple is seeing with so many circuit card components being replaced by one single chip.

What specific things will the Apple Silicon Mac’s not be able to do that the preceding Mac’s could?

Obviously we won’t be able to BootCamp and run 32-bit applications with an older system, but what else will not be possible?

Will we still be able to boot off an external device? I assume with the integration of system memory that memory upgrades on desktop Macs will be a thing of the past too. So much for getting around Apple’s overpriced memory premiums, or will this be still possible somehow? What might this mean for PCI based expansion cards? Will these still work when in a thunderbolt enclosure or directly installed in a Mac Pro?

I was quite surprised by the Thunderbolt/USB4 and RAM limitations. I see in the slide that they did show “Up to 16 GB” which I missed during the presentation. But the single external display and only 2 TB/USB4 ports came as a real surprise.

I was pretty dissatisfied with the level of technical detail in the keynote. They could have done better.

Bravo. Thanks for writing this clear Big Picture of the transformation that is underway and hiding in plain sight.