Apple is researching how "Apple Glass," or other future Apple AR devices, could skip tiny screens altogether, and instead use micro projectors to beam the images straight onto the wearer's retina.

Apple may soon have an entirely different meaning for its term "retina display." Rather than a screen whose resolution is so good our eyes can't distinguish individual pixels, there may not be a screen at all.

"Direct retinal projector," is a newly-granted patent, that claims this projecting right into the eyes could be best for AR. Specifically, it could prevent certain ways that watching AR or VR on a headset can cause headaches and sickness.

"Virtual reality (VR) allows users to experience and/or interact with an immersive artificial environment, such that the user feels as if they were physically in that environment," says the patent. "For example, virtual reality systems may display stereoscopic scenes to users in order to create an illusion of depth, and a computer may adjust the scene content in real-time to provide the illusion of the user moving within the scene."

We know all of this, but Apple wants to set the stage for how typical AR/VR systems work, and why there are problems. Then it wants to solve those problems.

"When the user views images through a virtual reality system, the user may thus feel as if they are moving within the scenes from a first-person point of view," it continues. "However, conventional virtual reality and augmented reality systems may suffer from accommodation-convergence mismatch problems that cause eyestrain, headaches, and/or nausea.:

"Accommodation-convergence mismatch arises when a VR or AR system effectively confuses the brain of a user," says Apple, "by generating scene content that does not match the depth expected by the brain based on the stereo convergence of the two eyes of the user."

You're wearing a headset and no matter how light Apple manages to make it, you're still conscious that you have a screen right in front of your face. Two screens, in fact, and right in front of your eyes.

So what you're watching, the AR or VR experience, might be showing you a panoramic virtual vista, perhaps with someone's avatar in the far distance, walking toward you. The AR/VR experience is telling your eyes to focus in that far distance, but what's being displayed is still actually, physically, exactly as close to your eyes as it ever was.

"For example, in a stereoscopic system the images displayed to the user may trick the eye(s) into focusing at a far distance while an image is physically being displayed at a closer distance," continues the patent. "In other words, the eyes may be attempting to focus on a different image plane or focal depth compared to the focal depth of the projected image, thereby leading to eyestrain and/or increasing mental stress."

Beyond the fact that this is obviously, as the patent says, "undesirable," there is a further issue. Today it's still the case that there is a limit to how long a user can comfortably wear an AR/VR headset.

Part of that is of course down to the size and weight of the headset, but it is also to do with these "accommodation-convergence mismatch problems." Apple says this can detract from a wearer's "endurance levels (i.e. tolerance) of virtual reality or augmented reality environments."

Projecting images into the wearer's eyes, by comparison, is a lot more like the way light usually comes into our vision as we look around. There have to be issues about the strength of projection, the brightness of the light source, but this patent doesn't cover those.

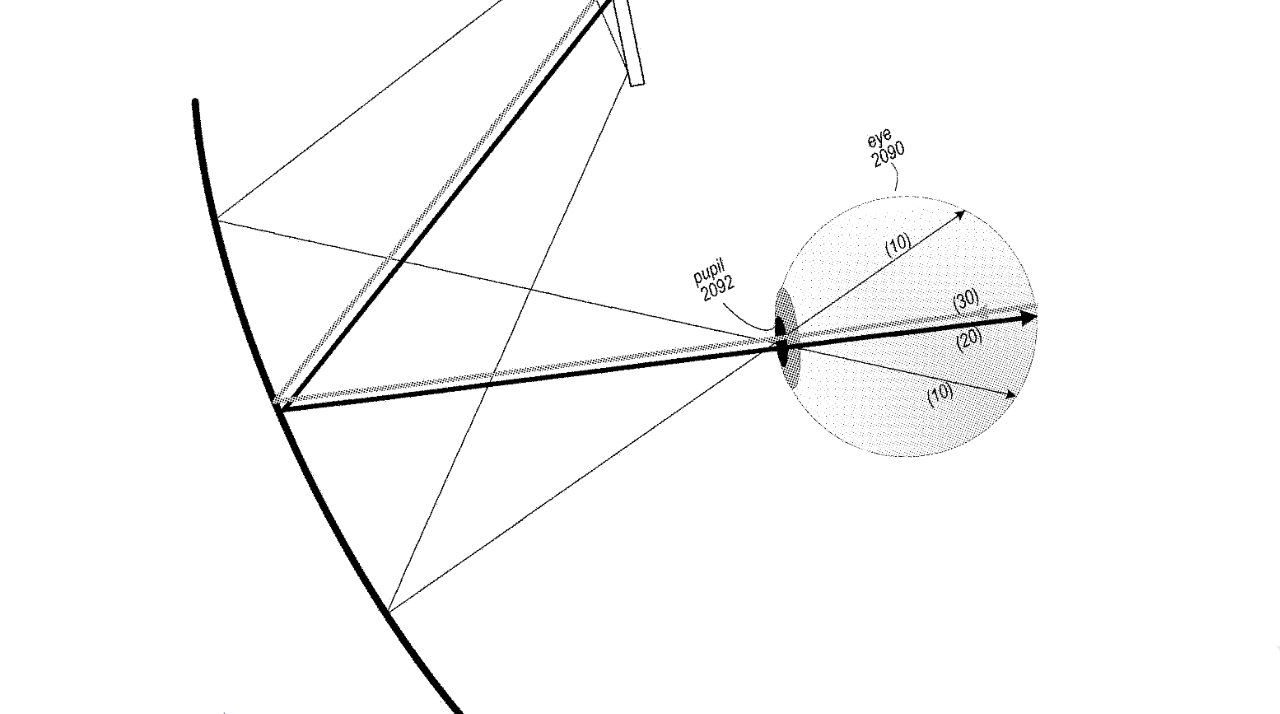

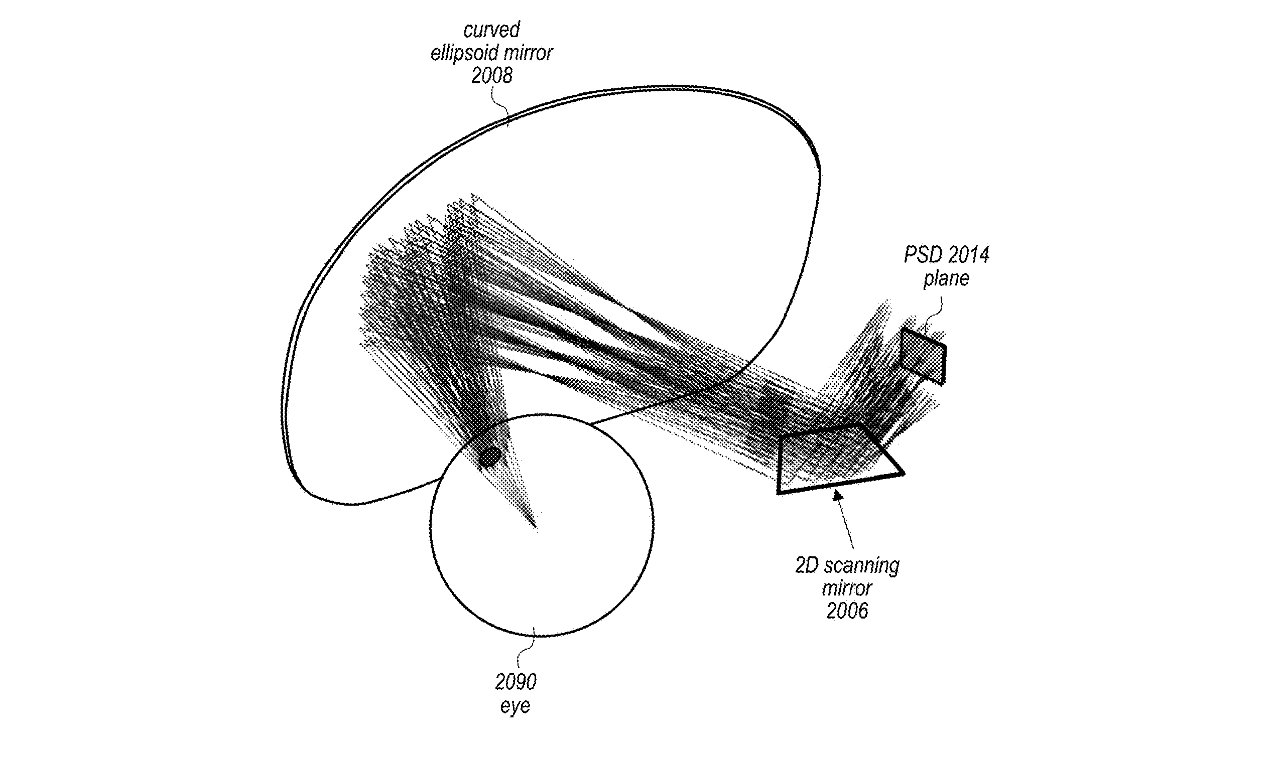

Rather, once it's made a case for using projection at all, the majority of the patent is spent on systems and methods for aiming correctly. The projection has to be precise, not just generally in shining into the eyes, but also what gets projected to which points.

Consequently, much of the patent about projecting into the eyes is also about what can be read back from those eyes. Specifically, Apple is once again investigating gaze tracking technology.

This new patent is credited to Richard J. Topliss; James H. Foster, and Alexander Shpunt. Topliss's previous work for Apple includes a patent for using AR to improve the Find My app.

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

-m.jpg)

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

-m.jpg)

15 Comments

...Hypnosis Capitalism...?

I wonder how this would work for people wearing contacts. Like, how would the apparatus know how much to correct for the refraction from those lenses? With AR glasses, I could imagine a calibration mechanism on either side of the glasses, but that's obviously to possible with contacts.

This reminds me of a sign a grocery clerk had near his scanner: