Apple's recycling program has come under fire, with employee theft and the destruction of working iPhones named as big problems in an examination of the environmental effort.

Apple has repeatedly promoted its green credentials when it comes to recycling old iPhones and other products handed over by customers via its trade-in program. By taking older customer devices off them, Apple is able to disassemble the hardware and potentially reuse some materials in future products.

However, a report from Bloomberg investigating the supply chain and related lawsuits claims that not all is well with the recycling effort. Due to Apple's stringent standards, recycling firms are constantly monitored to minimize the chance of product theft.

Recycling everything, no exceptions

The recycling program is, theoretically, quite simple to understand. A customer hands Apple an old iPhone, which is then passed over to an e-waste processor to disassemble the devices.

Once batteries and some other components are removed, the remaining parts are put through a shredder to turn it all into shards of material.

This process is also carried out with intensive scrutiny and secrecy, with locked doors, metal detectors, and surveillance cameras monitoring the actions of employees at facilities like GEEP Canada Inc. near Toronto.

Aside from Apple's famous culture of secrecy, the monitoring is in part to ensure that the recycling companies keep to their contracts. In part, that also means preventing employees from sneaking devices out the door.

The seemingly usable and undamaged iPhones and iPads that pass through the facilities were a temptation for some employees, which prompted a surprise audit by corporate investigators into GEEP's operations.

Apple discovered discrepancies in paperwork, as well as two bins of intact Apple Watch units hidden away from the cameras. Eventually, Apple accused GEEP of not recycling at least 99,975 items, including iPhones that were reactivated in China instead of being destroyed.

GEEP was sued in 2020 by Apple for $22.6 million for breach of contract, amid accusations there was a "carefully orchestrated scheme" by employees to resell hardware to the grey market. While GEEP acknowledged the issues, it blamed the incidents on "rogue employees."

However, four years later, there haven't been any further motions in the case, with it potentially being automatically dismissed within months.

The case wasn't just surprising due to the level of thefts, but observers were apparently amazed that Apple was forcing recycling partners to shred thousands of iPhones that could've easily been refurbished instead.

While GEEP is the prime example for the investigatory article, other recycling partners have faced similar pressures by Apple to make sure everything going through the doors is recycled, even if it looks pristine.

Long-term scrutiny

Part of the problem is that Apple is extremely demanding in having the devices destroyed by recyclers. It was a problem firms would be prepared to deal with since it could attract more e-waste clients.

From 2014, when Apple became GEEP's customer, thousands of products arrived at its facility to be destroyed. GEEP's Apple Cage required a metal detector to be installed, preventing components from exiting hidden inside employee clothes.

Though Apple mandated that devices had to be destroyed with 45 days of arrival, with representatives frequently monitoring goods arrivals and processing, it was still reasonably simple for items to go missing. One source told the report that pallets were moved around and mislabeled, but not at levels that caused people to ask questions.

The thefts included accounting and logistics tricks, including reclassifying shipments and altering records.

Other recyclers faced similar scrutiny and investigations from Apple, and also employed similar techniques. Sometimes, even more low-tech methods were used.

One example was an engineer taking advantage of a water cooler rolled in during shifts on a steel cart. The engineer taped iPhones to the bottom of the cart before it exited the cage, with the guard assuming the steel of the cart caused the metal detector to go off.

Shredding's not great, but necessary

Apple's focus on pulverizing old devices into fragments isn't necessarily the best way to deal with the older smartphones. Smelting can certainly return used materials to the supply chain, but that grows the per-device carbon footprint more than carefully disassembling and reusing components.

Even less of a carbon issue is if Apple allowed more of its recycled hardware to be reconditioned and resold. Doing so wouldn't require the massive carbon footprint of full-scale production, making it a lot cleaner in general.

Shredding does provide Apple with quite a few benefits, though. For a start, any chips with user data are destroyed, protecting the former customers from having that information leaked out.

The process also renders components like camera modules and chips from being reused to produce a "Frankenstein" device.

Apple has previously dealt with mass-scale iPhone repair fraud in China, which involved thieves buying iPhones from stores, taking components and replacing them with broken or fake versions, then returning the iPhones to be replaced.

Automation isn't quite good enough

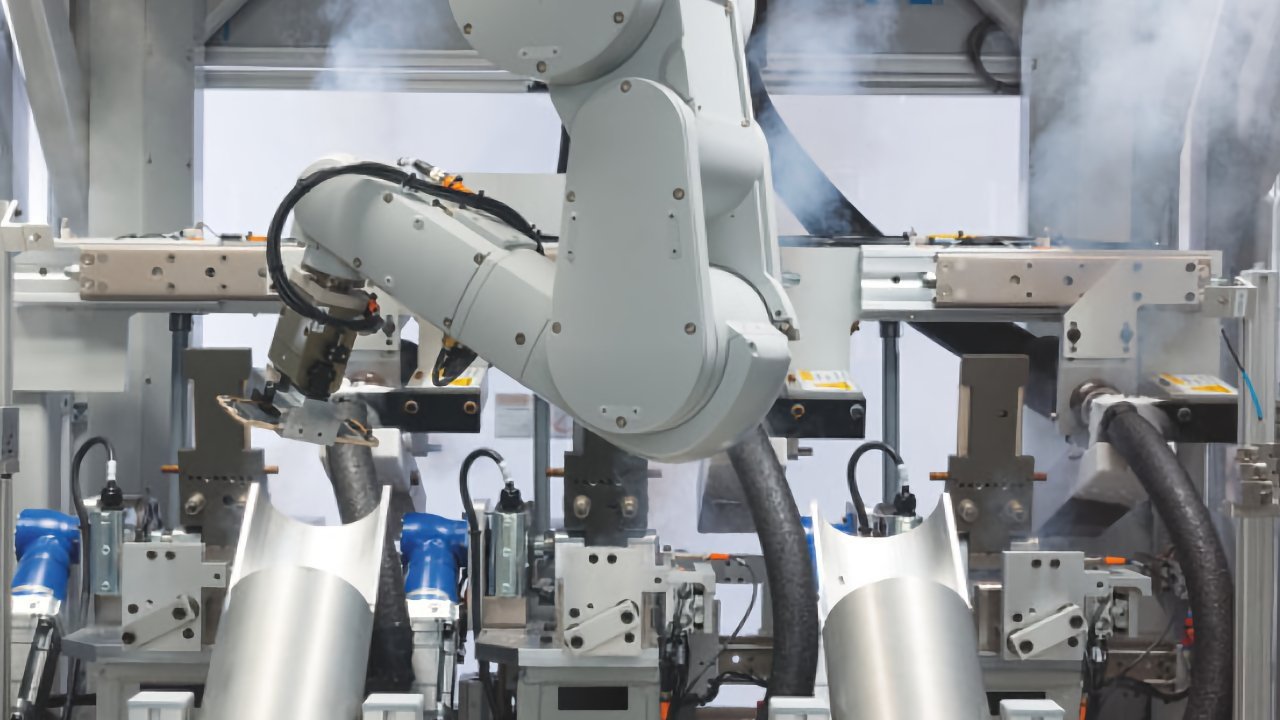

One answer to the recycling issue is to remove humans from the equation, but the report indicates that Apple's attempts haven't really helped that much.

Liam, the recycling robot, was only able to deal with one iPhone model, and supposedly did a poor job at it to the level that cleaner units were used for media demonstrations.

Daisy, the successor, was a lot more successful, albeit being more destructive in its approach when stripping down devices. Its ability to handle up to 200 units per hour and to deal with 15 iPhone models was a massive improvement.

Despite the improvement, and the existence of two Daisy robots in existence, the results didn't quite live up to the marketing-led expectations. It is thought that Apple's automated efforts manage to process just 1.2 million iPhones per year, or about two days worth of units sold by the company.

Evidently, while Liam and Daisy don't have any of the inclinations to pilfer iPhones they're supposed to be destroying, there's still a need for humans to do a lot of the work.

The temptation to steal the would-be-destroyed iPhones by employees, and Apple's intense surveillance of their work, will still be around for quite some time.

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

-m.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Oliver Haslam

Oliver Haslam

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

10 Comments

Is it really a surprise to most people? If Apple can’t make more money for themselves by reselling the traded in phone as refurbished they are going to make sure all the parts are destroyed to keep them from being available as spare parts for users and third party repairers. They will recover the materials that have actual street dollar value such as the aluminum but everything else is just going to be buried in a dump or shipped out to another country to be buried there.

On the one hand, if you sign a contract and are being paid for a job, you know what is being asked of you and audits will be part of the contract. No matter how stringent, Apple should be pursuing any company that is in breach of any agreement.

There will always be companies cutting corners and trying to scheme the system. That is the case in the EU too, even with clear guidelines in law so audits and investigations are part of the plan.

On the other hand, if Apple wants to make a big marketing deal out of recycling, safe disposal, re-use, carbon footprints and what not, it really should be offering up independently audited figures on how well the schemes work.

Just as design for repair should be a key goal, it goes without saying that design for EOL should be part of the same plan. Especially as we know that rare earth elements are highly desired goals in recycling. Shredding the rest is selling users short. Moreso in the EU, where the costs of elimination are included in the price of electronic and electrical goods.

Here is a video by the company they use to recycle the material:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=USVaYflXK2w

If the cameras and chips are just shredded, then it’s not really recycling at all.