Apple's second patent infringement trial against Samsung begins today, outlining a battle that the two sides are waging in very different ways. Apple will be expanding upon its legal strategy outlined in the first trial, while Samsung is starting over with an entirely new tactic aimed at devaluating Apple's inventions so it can continue using them for virtually nothing.

Why Apple won the first trial

In the initial lawsuit it filed in April 2011, Apple argued three utility (technology) patents and four design patents. It sought to prove to the jury that Apple's expensive, risky, years-long investment in developing iPhone and iPad as products was simply copied by its component supply partner Samsung, infringing upon its legal rights obtained after it filed for protection of hundreds of patents related to the unique iOS experience Apple had invented.

Samsung brought five patents of its own to the first trial. However, rather than representing unique technologies that Samsung had been using to differentiate its own products in the market, Samsung's asserted patents pertained to technical ideas within Standards Essential Patents previously committed to FRAND ("fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory") licensing.

Apple prevailed in convincing the jury that Samsung had infringed both its uniquely distinctive technologies and its trademarked overall appearance, largely using evidence generated by Samsung itself, including the 132 page "Copy Cat" internal document that detailed Samsung's efforts to copy the unique features of Apple's iPhone over just a period of a few months in order to deliver its own Galaxy line of devices that looked and worked so similarly to Apple's that customers could be expected confuse the two.

Why Samsung lost in the first trial

Samsung's efforts to leverage its own FRAND SEPs in the trial failed across the board, in part because of evidence that the SEP patents weren't even Samsung's inventions, but simply technical concepts the company had patented during the public negotiation of open standards.

It was as if Samsung had sat in on the community development of standardized, international freeway designs, filed to patent ideas as they were being openly discussed, then turned around and tried to claim ownership of ideas like onramps and lane striping after those ideas had been written into standard specifications of how the roads would need to be designed.

As a report by the Wall Street Journal observed in late 2011 regarding the company's use of FRAND SEPs in lawsuits, "it appears that Samsung is trying to sow confusion among courts world-wide over different types of patents.""It appears that Samsung is trying to sow confusion among courts world-wide over different types of patents" -Wall Street Journal

Samsung's abuse of FRAND SEPs in this and other trials worldwide was outrageous enough to spark government investigations in the U.S., E.U. and even South Korea, all aimed at curbing the weaponized use of SEPs, which are intended to create interoperability among competitors, rather than protect inventions that uniquely differentiate a single company's products.

As an example, Samsung's U.S. Patent 7,362,867 from the first trial describes an idea required to build the baseband chips that allow smartphones to connect to carriers' mobile wireless towers. Apple's baseband component suppliers had already paid Samsung to license these "Standard Essential" ideas, but Samsung sought to allege that Apple's iPhone was still infringing.

Essentially, Samsung tried to accuse Apple of shoplifting a product that Samsung's own customers had already paid for before walking out of the store and selling it to Apple for resale. The jury didn't buy this tactic, but that argument did manage to make its way through a parallel U.S. International Trade Commission court, resulting in the threat of a sales ban of certain iOS products despite the fact that Samsung's patent in question had already been deemed invalid the previous year.

It took a Presidential veto to stop Samsung from obstructing Apple's sales with a known-to-be-invalid patent leveraged in an ownership claim so specious and easily torn apart that Samsung has subsequently appeared to have abandoned attempts to repeat the same sort of arguments in the second trial.

Apple's second trial doubles down on differentiating tech patents

For its second trial, Apple has scaled back the hundreds of iPhone patents it could leverage in court down to five key patents (down from around eleven in the original filing) that are relatively easy to present to a jury. There are no Apple design patents in this case, only utility patents with clear relevance to Apple's allegations that Samsung willingly copied differentiating features of Apple's products to confuse the market and avoid having to invest years of its own efforts into crafting an original mobile experience.

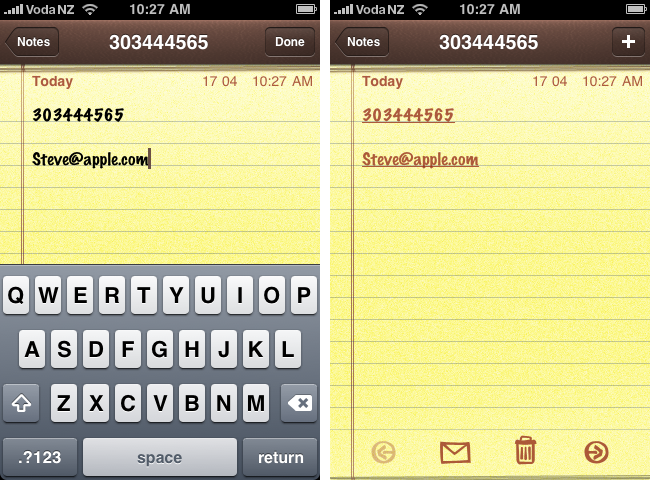

In summary, the five patents Apple is wielding in the second trial pertain to iOS slide to unlock; auto word correction and suggestion used in spellcheck; Spotlight universal search of local phone and internet content using heuristics to suggest relevant results; iTunes/iCloud-style background device sync with a PC or the cloud while being used; and automatic quick links, also known as Apple Data Detectors (depicted below).

Apple is focusing its case on these five patents to prove two points. First, that Apple's engineers over a series of years developed unique, differentiating features that are now well known and closely associated with the iOS experience, setting Apple's products apart from other maker's mobile devices.

And, secondly, that Samsung owes Apple significant damages, both for using Apple's technology to earn billions of dollars worth of its own mobile profits (as Samsung's attorneys have admitted, and to cover the lost profits Apple suffered after being forced to compete against stolen copies of its own work, which were offered by Samsung at a lower price.

Samsung: patents aren't worth much, not even ours

Already, the significant damages that Apple is seeking in the second trial have received criticism for being "too high," even before Apple has argued its case. Of course, it's in Samsung's best interests to argue that patents aren't really worth very much at all. That appears to be the core of Samsung's new strategy in the second trial.Samsung's patents for the second trial were acquired from third parties simply to have something to present at trial

Despite having been in the smartphone business for many years before Apple, Samsung has not successfully brought its own utility patents to trial against Apple.

After losing across the board on its FRAND SEP strategy, Samsung is back with a countersuit alleging Apple infringement of two patents. It started the second trial with four, but dropped two of its own SEP patents earlier this month: U.S. Patent No. 7,756,087 and U.S. Patent No. 7,551,596 both of which related to technical details of transferring data over a mobile link.

Samsung has represented in various cases that, just like Apple, it too has a heritage of invention and technical innovation encapsulated in a broad patent portfolio, but none of the patents Samsung is bringing to the second trial involve concepts that smartphone or tablet customers would recognize as being unique inventions of Samsung.

In fact, Samsung's entire patent response to Apple's claims in this second case are made up of two patents the South Korean conglomerate acquired from third parties, simply to have something to present at trial.

One of those patents, U.S. Patent No. 5,579,239 was acquired by Samsung in October 2011, six months after Apple filed its second lawsuit. Samsung bought the patent, which claims ownership of the overall concept of sending video over a network (depicted below), from a patent application group living in Oklahoma when the patent was originally filed back in 1996.

The other patent Samsung is using, U.S. Patent No. 6,226,449, was similarly acquired from Hitachi in August 2011. It claims ownership of the idea of "recording and reproducing digital image and speech," and was originally filed by Hitachi in 1997.

So while Samsung is making a case to the public that both it and Apple have lots of patented technologies in the mobile arena that differentiate their respective products, the reality is that for its second trial, Samsung had to go out and buy a defense using patents others had filed nearly twenty years ago. At no point over the last twenty years has either of those patents ever differentiated Samsung's products.

Samsung is also highlighting that it doesn't expect much in the way of damages from its pair of acquired patents. It's only asking for total damages of around $7 million from Apple, in stark contrast to Apple's demands of around $2 billion. Samsung's new legal strategy therefore seems to be aimed at attacking the entire notion that patents have any real value at all.

That's a tactic that, if successful, could enable Samsung to continue to appropriate Apple's patented, differentiated features at very low cost, even if Apple keeps initiating new lawsuits and keeps winning awards from juries, a process that takes years to wind its way through the courts.

The tech media seems to be buying into Samsung's new strategy. In a CNET article entitled "Apple v. Samsung: All you need to know about latest patent trial," Shara Tibken wrote, "Apple wants about $2 billion from Samsung. Samsung, meanwhile, is asking for much less because it believes royalties shouldn't be so high."

Samsung's role reversal in demanding billions in patent royalties

Samsung's new strategy of attempting to devalue everyone else's patents by assigning a very low valuation to some of its own is a notable reversal of the company's previous "beliefs" reflected in its demand for roughly $3 billion in royalties from Apple over that baseband patent from last fall, noted above.

Samsung was demanding around $16 per iPhone in SEP royalties from Apple on a baseband chip that cost only $11.72, a component that had already bundled in the manufacturer's cost of paying Samsung to license its patent portfolio. Contrast that with the roughly $40 royalty Apple is now asking for Samsung's infringement of five different patents that each define key elements of the iOS experience.

Unlike the "Standard Essential" aspect of patents involved in those baseband chips, Samsung can build phones that don't infringe upon Apple's five patents. Samsung can even modify its own products to simply stop presenting Apple's patented features as its own.

After years of Apple building unique, patented features like Spotlight and Apple Data Detectors to differentiate its products in the market place, it's not hard to fathom why Apple now sees itself in a position of strength to argue that Samsung owes it significant damages for having failed to either negotiate the licensed use of Apple's technologies, or agree to build its own parallel solutions that work around Apple's patents in non-infringing ways.

Samsung has reason to think its policy of infringement is winning

At the same time, Samsung also appears to believe it is in a position of strength, because despite having lost a nearly $1 billion verdict in the first case, it managed to not only earn multiple billions of dollars from appropriating Apple's design patents (Samsung Mobile reports earnings of roughly $5 billion per quarter) but also managed to avoid any sales injunctions that would force it to stop infringing those original patents. Compared to a more favorable judgement that could have resulted in damages of $3 billion or more, on top of a punitive injunction sales on Galaxy shipments, Samsung might likely believe that it won the first trial

Recall too that Apple originally sued for around $2.5 billion in damages in the first trial and ended up with an award closer to $1 billion. After that, Apple asked for a damages multiple that would have resulted in $3 billion in damages. That request was denied, along with Apple's requests for an injunction against sales of Samsung's infringing products.

Compared to a more favorable judgement that could have resulted in damages of $3 billion or more, on top of a punitive injunction sales on Galaxy shipments, Samsung might likely believe that it won the first trial.

If it can whittle down two more years of Apple's legal efforts into another slim fraction of its quarterly profits from Galaxy sales, Samsung may just shrug off a billion dollar biennial payoff to Apple as a cost of doing business going forward, in line with the "tax evasion, bribery and price-fixing" that The Independent recently profiled as defining Samsung as a company that sees itself as above the law.

Samsung's big risky bet against patents

Back in August 2011, months after Apple had filed its first lawsuits against Samsung in both U.S. Court and with the ITC, Samsung had an opportunity to avoid a second lawsuit by negotiating patent royalties with Apple, the same way HTC agreed to settle with Apple in late 2012.

However, even back then Apple would have had the upper hand in negotiating a deal: it had patents in hand that were known throughout the industry to be valuable in practice, as Apple's unique, premium iPhone and iPad products were garnering disproportional interest from consumers, and therefore disproportional profits in the industry.

Samsung's delay tactics have resulted in strengthening Apple's bargaining position, because in the years since, Apple won its first U.S. patent case and Samsung has lost every significant case in trials spanning the globe.

The only way Samsung can improve its position in trying to retroactively strike a deal with Apple is to convince the world's courts that patents are not worth the very valuations that Samsung itself sought to collect from Apple right up into the end of last year.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

49 Comments

[IMG ALT=""]http://forums.appleinsider.com/content/type/61/id/41046/width/350/height/700[/IMG]

If you transpose some of these comments to touchscreens you might observe that strategic Apple patents are surreptitiously owning the screen manufacturers. Handcuffing those that makes the hardware is a dangerous tactic unless long term you are happy to use only bottom rung suppliers.

So this is all just some game that lawyers play. Like Samsung’s product strategy, they just throw stuff at the wall and see if anything sticks.

Don't link to CNet, seriously.

What I personally don't understand about this whole thing, is that AFAIK... Apple didn't even want to license their patents at all. There were some talks, but they went nowhere... again AFAIK. So with a "well then screw 'em if they think they can just steal or stuff" type of attitude, why didn't Apple just go into 10's of Billions, rather than just 4B? What does "not for sale at any cost" mean going forward, if a judge can determine at a later date what that "priceless" object, technology or design "should be" sold at after the fact that a company stole and used it to make money. Why should Apple even be forced to guess what they lost in sales, as opposed to taking every cent from the selling price of a device that was based on copying their design unlawfully. I don't even think it is the burden of Apple or a jury to determine how many Samsung devices "theoretically would be sold" regardless of Samsung's thievery. Show numbers shipped, sold or any exchange of currency... and that is the price to be paid after losing the trial. Period. That would put an end to "blatant" theft immediately, which this is considering the undeniable evidence. Also you have to wonder what the other Android OEMs point of view is on this, after they stuck to the rules and lost valuable brand and market share to Samsung. I would've expected them to be a little more vocal backing Apple up on this. They're the ones that have suffered the most financial damage.