Inside Apple's 2016 MacBook Pro: Graphics processing unit choices

Once again, Apple probably won't rock the boat with any new MacBook Pro, and will likely stick with Intel integrated graphics and lower end next-generation discrete GPUs rather than giving macOS users faster options.

Long-time Apple consumers have a vision in mind of what they expect from a Pro-designated modern Mac. Users expect the fastest processors, the most memory, fast drives, and speedy graphics processing.

None of those expectations are met by the currently shipping Apple Mac product line, however. The Mac Pro was refreshed in 2013, and has sat unrevised since. The MacBook Pro did get updated in 2015, but because of varying factors, some benchmarks fell behind previous years' models.

We believe that the high-end 15-inch 2016 MacBook Pro will have a new AMD "Polaris" GPU, while lower-end 15-inch models and all 13-inch models will feature Intel integrated graphics.

While new and faster Thunderbolt and USB interfaces may be the most obvious looking at the outside of new computer, performance can be greatly enhanced, or hurt, by Apple's choice of a graphics processing unit (GPU). Apple's history of GPU inclusion in its products hasn't been consistently great, though.

Recent developments in the GPU market may change all that.

AMD has in recent years broken the Nvidia monopoly on stand-alone GPUs in the Mac. In the wider marketplace, the two are going head-to-head with very recent and very powerful GPU releases.

Based on these developments, and Apple's current marketplace biases, we believe that any 2016 MacBook Pro revision will have a new AMD "Polaris" GPU on the high end, and will skip faster offerings or GPUs from any other vendor, despite availability. We also believe that Apple will continue its "good enough" trend and will stick with integrated Intel graphics on the lower end MacBook Pro, and any 13-inch MacBook Pro.

To understand why takes some examination.

Needs for off-CPU graphics processing have always existed

Co-processors for dealing with graphics have been around since the '70s. Development was driven by the game industry first, and the scientific community more recently.

The '80s and '90s saw the first predecessors to the GPU, with wide use of blitter chips for video by the early '90s. Blitter chips were sub-processors originally designed to move and modify data in RAM rapidly in sync with display refresh rates, eliminating load on the main processor in a time where CPU clock speed was measured in megahertz and could be counted on the fingers of two hands.

As video arcade machine technology developed, demand grew for hardware-accelerated 3d graphics in the growing home computer market. The term "graphical processing unit" dates back to the late '90s as a marketing term.

Speaking of the late '90s, development of 3D APIs split during this time between OpenGL, and Microsoft's DirectX. OpenGL and its direct descendant, OpenCL, are used heavily by Apple in the macOS, and iOS to this day.

For a brief time in the relatively early days of GPU development, Apple held the crown for 3D rendering performance with the 16MB ATI Rage 128 card in the blue and white G3 tower.

Turn of the century

Released in 2001, The Nvidia GeForce 3 can be considered the first "modern" GPU, encapsulating the first use of programmable shading, rather than the earlier less efficient approach of "hardware transform and lighting." Floating point math was added in 2002 to many GPUs.

In 2006, the GeForce 8 series was introduced with clusters of processors working in tandem, making scientific calculations feasible on the GPU. Nvidia's CUDA platform (not to be confused with Apple's relatively early CUDA power management chip), introduced in 2007, was the first "standard" for GPU computing.

The advent of powerful, general purpose mobile devices, heralded by the iPhone, forced GPU developers to consider both power consumption and computing power. Manufacturing techniques intended for mobile started crossing over into GPU development around this time.

Since 2007, AMD and Nvidia have moved to control nearly 100 percent of the consumer GPU market.

Apple's checkered GPU past

Industry-wide, most computers shipped up through 2007 had poorly performing integrated graphics, but Apple's offerings generally had dedicated graphics. Any GPU expansion or upgrading during that time was performed through an AGP, PCI, or PCI-e slot — notably absent on Apple's desktop iMac and Mac mini lines, to say nothing of laptop computers.

In between the blue and white G3 and the 2013 rebirth of the Mac Pro, Apple's GPU offerings even in build-to-order configurations have never been top of the line in any product. As an example, when the Mac mini graduated from the G4 processor, updated with the Intel Core-family it was saddled with Intel GMA950 integrated graphics for a while.

With the help of Nvidia-supplied drivers, the 2008 Mac Pro through 2012 Mac Pro can take some modern graphics cards, and associated CUDA-related software through the PCI-e interface. Performance is constrained somewhat on the 2008 Mac Pro as a result of architectural limitations in the now eight-year-old computer.

The 2013 Mac Pro that replaced the 2012 Mac Pro tower was revolutionary for its time. The AMD FirePro D300, D500, and D700 GPUs outclassed anything else available on the market.

Time has marched on. From a raw processing power standpoint, the D700 is capable of 3.5 teraflops of computing power, where the GTX 980 PCI-e GPU released in 2015 benchmarks at 6.4 teraflops.

Three years hasn't led to that much improvement in Intel's CPU offerings other than power efficiency, but clearly, GPU technology has leapt forward in that time.

Laptop as portable computing powerhouse?

Apple's shift to laptop components for a large swath of its product line has led to less powerful mobile discrete GPU chipsets being included, or reliance on Intel integrated video chipsets. Even if the D700 was made available in a mobile form, power consumption issues would prevent long battery life from a portable, which the modern computing market seems to value more than processing power in recent years.

Intel CPU development has stagnated speed-wise in recent years, leading to a situation where the 2012 15-inch i7 Retina MacBook Pro remains competitive with the 2015 model, and in some cases, outperforms it. Apple has been roundly criticized for infrequent updates, but the problem is clearly multi-fold.

The biggest loss in Apple's failure to frequently update hardware as of late isn't in CPU performance, but is in the advancement of GPU technology. The on-board graphics capability of Intel processors stands far above that of just a few years ago, but it is still remarkably limited when compared to dedicated mobile chipsets.

Half of the picture

Nvidia has supplied the slim unibody iMac with mobile-class GPU chipsets since 2012. Other Nvidia offerings dot the Apple product line alongside competitor AMD.

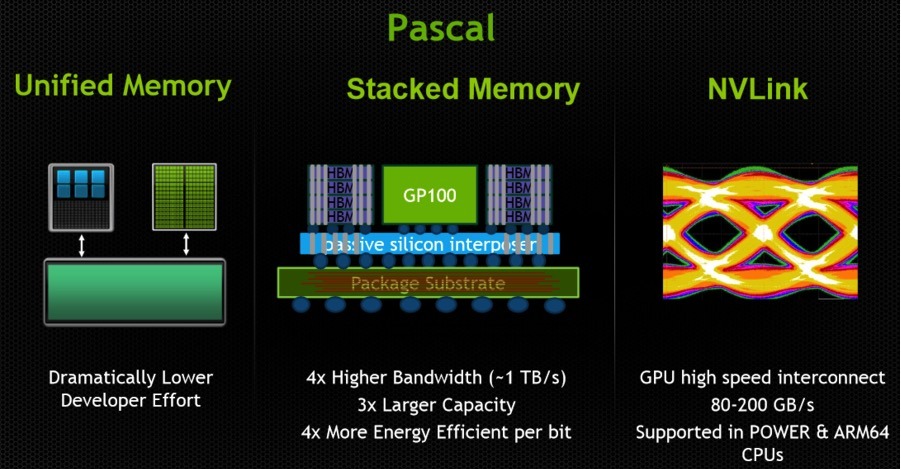

In July, Nvidia announced the 1000-series PCI-e interface GPU, based on the company's "Pascal" architecture. While the low-end 1060 chip is not faster than the previous generation's high-end 980 that crushes the D700 performance-wise, there are significant gains across the board in power management over previous generations.

The Nvidia "Pascal" technology is the culmination of a decade of work spanning desktop and mobile processors. The raw speed of the desktop GPU has been cross-pollinated with the power-sipping needs of mobile devices during the development of the new GPU line.

In August, the "mobile" versions of the 1000-series Nvidia GPUs were announced. For the first time, there are only minor differences between the laptop versions and the desktop versions. Nvidia claims that the mobile version of the new GPU is within 10 percent of the desktop model it was based on.

Desktop to mobile versions performance of previous chip architectures varied widely. Performance gaps between the two generally ranged between 30 and 50 percent, depending on implementation, with Apple generally choosing to slow down a GPU further opening the gap to cut down on heat, and improve battery life.

The other side

After the 2006 purchase of ATI Technologies, AMD has supplied Radeon-branded GPUs to Apple for some time. The AMD M290, M380, and M390 families drive the Retina iMac line, with the sole exception of one 4K iMac using Intel Iris Pro integrated graphics.

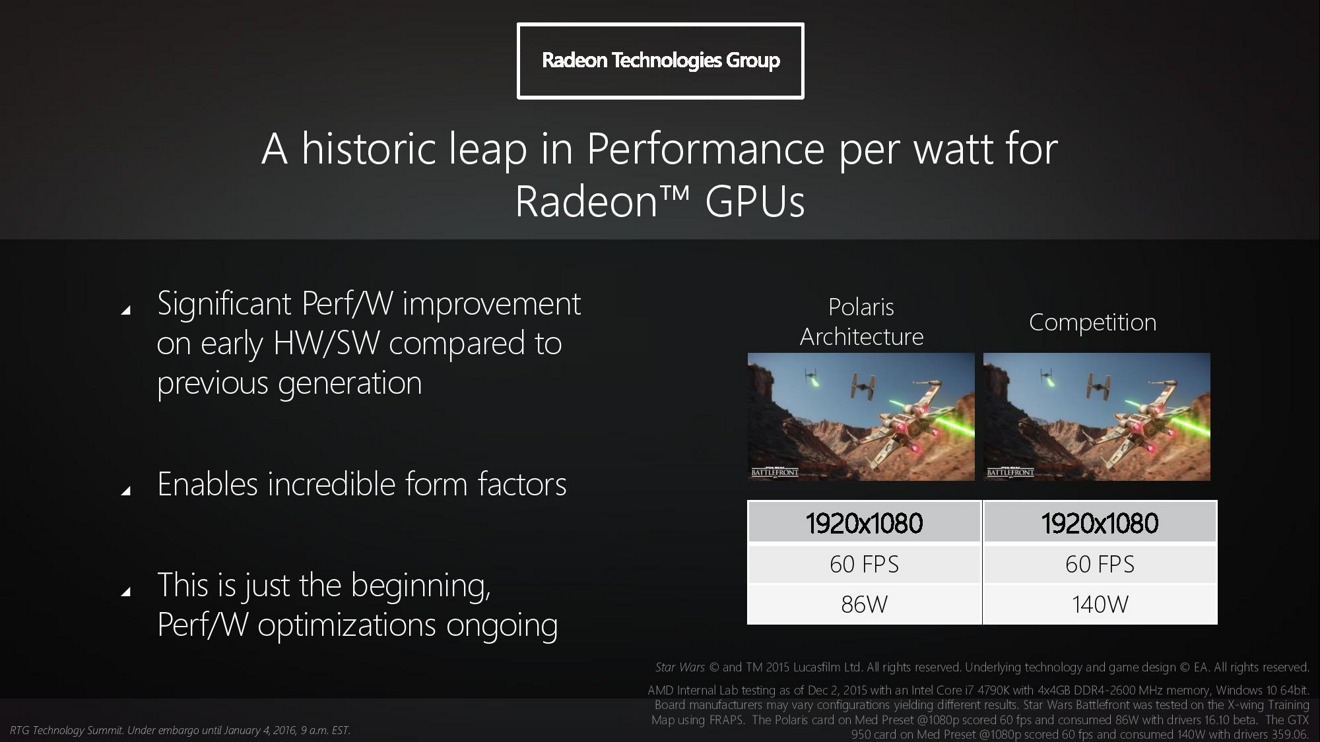

AMD also has a new GPU series. The "Polaris" RX 400 series was revealed in the spring, and just started shipping to retailers in PCI-e expansion card form. The company boasts 5.8 teraflops performance in the high-end version of the card, in what may be a more cost-effective deployment than the nVidia alternatives, at least for now.

However, any drivers for an AMD inclusion in a new MacBook Pro would necessitate a custom driver package. Nvidia does most of the "heavy lifting" for macOS coding, and AppleInsider has learned that Apple does the vast majority of the coding for AMD GPUs included in its products. However, most of the work has already been done on this, as AMD GPUs dominate the current Retina iMac line.

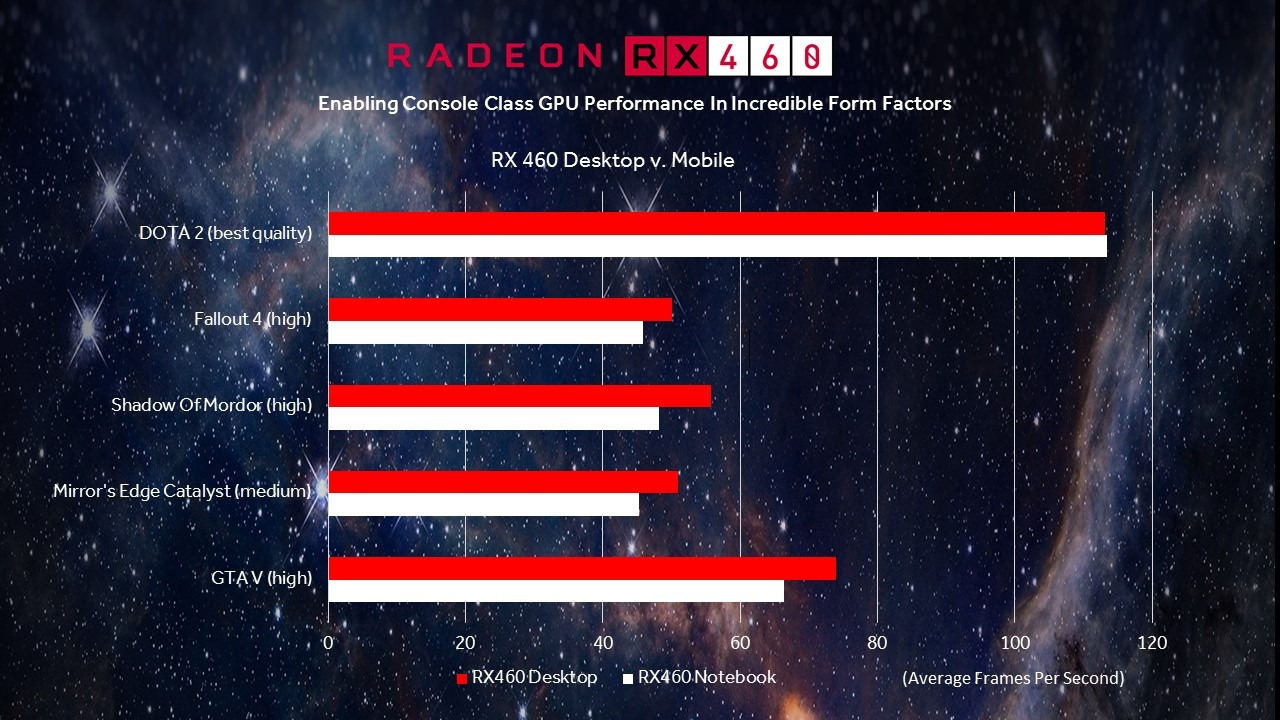

Very recently, a new gaming laptop was revealed, utilizing the first mobile variant of the RX 400 "Polaris" technology. The limited edition HP Omen has a mobile version of the RX 460 chip, with HP and AMD claiming that the laptop has only a very few frames per second difference between it, and the desktop version of the GPU.

Prior to the refresh of the HP Omen gaming computer line, only vague promises of future deliveries of a mobile AMD "Polaris" chip had been made.

Based on manufacturing similarities, and the alleged performance of the AMD RX 460 for mobile, higher-end AMD Polaris-based chipsets for laptops than the RX 460 will have similar power demands and performance as the announced Nvidia 1000-series GPU's mobile variants. But, we aren't expecting to see either Nvidia nor higher-end AMD GPUs in the MacBook Pro.

Big concerns abound

As we mentioned in the first part of the series, the new Intel "Kaby Lake" processor suitable for the MacBook Pro isn't expected for another few months, so improvements in the on-board graphics processing routines with the new processor won't be realized. Issues surrounding a potential MacBook Pro CPU will be delved into in a future installment of this series, but at this point we don't think that the imminent MacBook Pro refresh will have the seventh generation of the Intel Core-series processor in it.

So, omitting "Kaby Lake" leaves the sixth generation "Skylake" processor. Integrated graphics chipsets are greatly more advanced, and feature higher performance than in years past. Advantages in power consumption for omitting a dedicated GPU cannot be denied.

Combining the two factors in favor of integrated graphics clearly points to a reason to omit a dedicated GPU in the low-end MacBook Pro refresh. However, Apple's recent predilection to using them in "Pro" level gear is problematic, even more so given the relative age of the "Skylake" processor.

Given the state of the GPU market, continued use of AMD GPUs seems likely with the "Polaris"-series chip seemingly obvious for the new MacBook Pro despite only the low-end version of the chip ready for mobile for the fall. Certainly not guaranteed, but obvious.

Apple sold 4.3 million Macs in its third quarter of 2016 that wrapped up in June, generating $5.2 billion. In the same quarter, it sold 40.4 million iPhones, resulting in revenue of $24 billion.

The focus of the company has changed, and with it, the consumer type that it homes in on. The 2015 MacBook rebirth is a perfect example of that, and the very long period of time between the last MacBook Pro refresh and now is astounding, and telling.

Apple will continue to make Macs, if for no other reason than to support its iOS, watchOS, and tvOS development initiatives. In the pursuit of a new and larger customer base which have different aims and goals than previous Apple purchasers, new machines may just not have the level of graphical performance that long-term Mac aficionados clamor for.

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Michael Stroup

Michael Stroup

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele