In this series:

iPhone 4 and iOS vs. Android: hardware features

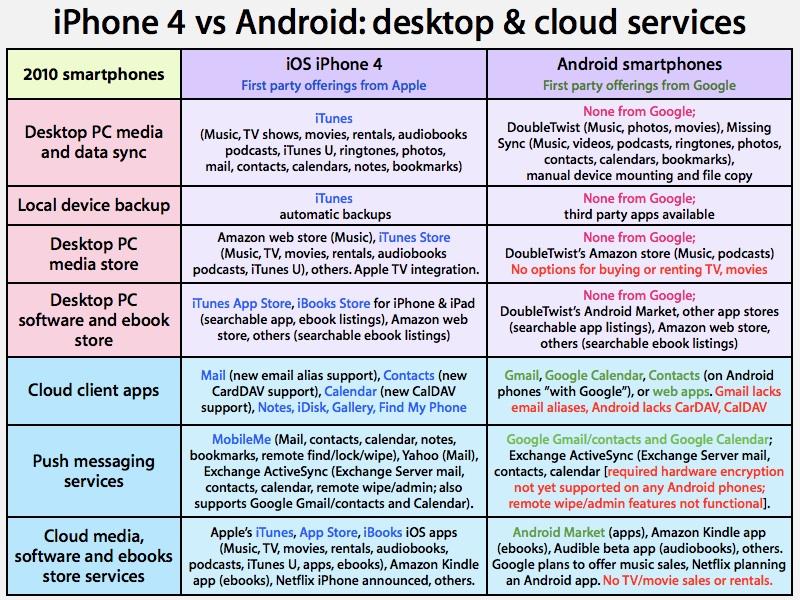

iPhone 4 and iOS vs. Android: desktop and cloud services

Over the last decade, Apple has constructed a rich digital hub centered around iTunes, handling local device backup and the syncing, organizing, and management of user data (photos, email, calendars, contacts, notes, browser bookmarks), media services (music, audiobooks, TV shows, movies, videos, podcasts, iTunes U content), mobile apps, and the iOS itself.

This is unique among smartphone platforms (including Google's Android), all of which rely upon mobile carriers to deliver "over the air" software updates to their devices, and also rely upon such "cloud services" to provide device and data backup, media streaming and sales, online app and ebook stores, and push messaging services, including email and calendar events.

Apple began adding cloud access (a shorthand term for Internet services that don't require a middleman PC) in 2007 with the WiFi iTunes Store, then extended its desktop-based .Mac cloud service to iPhone users in 2008 with the renamed MobileMe, which provides push messaging (mail, contacts, calendar and notes), remote device find/message/alarm/lock/wipe management features, and cloud storage of documents (iDisk) and media files (Gallery).

Apple also opened a device-based cloud version of the iTunes App Store, and most recently has extended iBook support to the iPhone as well. All of these cloud stores maintain sync with content purchased, backed up, and cataloged in the desktop iTunes on the Mac and PC.

Google's Android platform is designed to be entirely cloud based; there's no equivalent to an iTunes desktop app from the company, although the third party DoubleTwist serves as a partial alternative, providing desktop access to Google's Android Market, Amazon's media store, and a podcast library. DoubleTwist is also available for a variety of other devices that lack an iTunes of their own, including RIM's BlackBerry, HP's Palm Pre, and Sony's PSP.

Other third party Android offerings also bridge the gaps in Android's out of the box experience, such as Amazon's Kindle app, which provides an online ebook store, and Missing Sync, which offers to sync music, videos, podcasts, ringtones, photos, contacts, calendars, and bookmarks.

Google's own Gmail, Calendar, Docs, and other cloud-based services are accessible from Android phones, using either the "with Google" Android apps or via the company's web-based apps from Android phones that don't bundle them. Google plans to open a future competitor to Apple's iTunes Music Store (and Amazon's) for Android that enables cloud-based streaming of media.

The dark side of the Cloud

The drawback to Google's cloud-only strategy for Android is that cloud services are notorious for falling offline and for losing users' data. From Microsoft's Danger, to the Palm Pre and Nokia's Ovi service, to RIM's BlackBerry NOC, everyone who has offered cloud services for smartphones has also lost users' data. That maxim also applies to both Google and Apple, which like everyone else in the industry has inadvertently interrupted services and lost user data related to their cloud operations.

However, with iTunes and its "local backups by default" design, if your cloud services fail (and history indicates they will at some point), you can always revert to a local copy of your data you own and control. Google's Android, like Microsoft, RIM, and other mobile platform vendors, not only bets that cloud services won't ever fail, but also puts users' backups in the cloud, ensuring that when they do fail, users will be completely helpless unless they've created a personal strategy to make their own local backups. Which nobody does, even when there is a way to do this.

Apple currently enjoys a strong lead in offering iTunes as a silver lining for cloud failures. Every iPhone is automatically backed up locally by default, making device replacement and upgrades easy and painless. Because Google and other vendors are focusing on improving and extending their cloud offerings, it looks like Apple will continue to enjoy an increasingly strong position with iTunes as a local sync hub, a factor that will prevent many iTunes users from even considering alternatives to iPhone, regardless of any potential, real advantages offered by Android. At the same time, Apple is pushing ahead its own cloud services in tandem with (and well integrated with) iTunes.

On page 2 of 3: MobileMe isn't free, Exchange Server & open enterprise cloud services support.

On the other hand, while Google's online services (Gmail and Calendar/Contacts, with both sync and push messaging) are free (with ads), Apple's tightly integrated MobileMe service isn't. Of course, you don't have to pay for MobileMe to use your iPhone; it works just as easily with Google's free services as Android does, and in some cases is actually better. MobileMe is also not very expensive. At $69/year (with a new phone purchase, or from Amazon), it's less than $6/month.

In its previous form under the name .Mac, Apple's cloud service made some sense for users who wanted a simple messaging and content sync service that just worked. When Apple made it part of iPhone OS 2.0, it greatly enhanced the service conceptually with push services. But push came to shove, and the service debuted in flames of catastrophe.

Since that rough introduction, Apple has resolved its availability issues and introduced new apps that expose the services' features: iDisk for cloud file access, Gallery for uploaded pictures and movies, and most recently, Find My Phone, in addition to the built in apps that support sync: Mail, Contacts, Calendar, and Notes. At the same time, Apple has now downplayed MobileMe's web hosting services, focusing its efforts on mobile cloud sync between iOS devices and the Mac or Windows desktop.

MobileMe isn't the most generous file and web hosting service, and certainly isn't the cheapest email, calendar & contact cloud service (although it is very affordable compared to hosted Exchange or BlackBerry push messaging services). What it does offer is a pretty complete set of unique features in a single package from one vendor, complete with push messaging, email aliases (something that is not supported from Gmail, but is now fully and automatically supported as sendable email addresses in iOS 4), iDisk file sharing with password protected sharing (useful for sending large file attachments that are too big to email), Gallery for direct photo and movie sharing, web browser bookmark sync, and the Back To My Mac and Find My iPhone features.

Most of those features can be assembled from various third party offerings on Android phones, but doing so requires multiple accounts and different vendors to complain to when things stop working correctly. Roll MobileMe in with Apple's App Store, iBooks, and iTunes music, audiobooks and movies (with rentals, something Android is missing support for entirely), and you get one account and a bunch of services that all work pretty seamlessly through tight integration from one vendor.

That's not to say MobileMe and Apple's other cloud services are perfect; the company should really integrate Gallery into iOS 4's Photos app, and things like Notes sync (new in iOS 4) don't always appear to work flawlessly yet. However, just as Apple has kept the latest iPhone 4 ahead of Android in terms of hardware features (which it wasn't supposed to be able to do, given Android's multiple hardware partners), it's also managed to keep its cloud features a couple steps ahead of Google's (also a seemingly improbable task, given Google's apparent home court advantage in offering cloud-based services), while also offering a solid foundation of "non-cloud" services within iTunes, something that no other smartphone maker has caught up with yet.

On page 3 of 3: Exchange Server & open enterprise cloud services support.

Apple originally marketed MobileMe as "Exchange for the rest of us," but the company also built Exchange ActiveSync support into iPhone OS 2.0 in order to also support push messaging for corporate users.

While the Android OS offers rudimentary support for Exchange Server sync, it fails to handle the remote wipe and other administration features (such as fleet provisioning and centralized enforcement of security policies) that Apple has increasingly perfected for iPhone users over the past two years.

Android hardware also lacks support for hardware encryption, making the devices ineligible for support by the default security policy of Exchange Server. Third party software for Android can only improve the situation by misrepresenting the security profile of the phone to fool Exchange into supporting Android phones. Apple's iPhone 3GS introduced hardware encryption features last year, but newer Android phones such as the Google Nexus One and Motorola Verizon Droid still don't support corporate use.

Additionally, part of Android's "openness" means that apps don't have to be signed by a trusted Certificate Authority; anyone can self-sign an app and distribute it. In fact, most Android apps are self-signed due to the hobbyist nature of the Android Marketplace. That does not make Android phones attractive to corporate users working in a secure environment.

Apple requires that all iOS apps in the App Store are signed using a developer certificate it issues, enabling it to revoke certificates for rogue apps or malicious developers. While Apple offers its corporate users tools to distribute their own internal apps using self-signed certificates, the App Store library is curated and secure, setting it apart from the shareware nature of Android and its app library using meaningless, randomly sourced self-signed certificates.

Open enterprise cloud services support

In addition to its own MobileMe service and support for Exchange Server ActiveSync (which is also used to give iOS devices sync support for Google's Gmail and Google Calendar cloud services), Apple is also building open source, standards based calendar and contact services in Mac OS X Server. iOS 4 adds support for the emerging CalDAV and CardDAV protocols used by Mac OS X Server, which are also supported by other third party products including Kerio, Scalix, Yahoo Calendar and Zimbra.

As open specifications, CalDAV and CardDAV enable companies and institutions to set up their own messaging servers and enable their mobile clients to access these using iOS 4. Google is a member of the teams working on CalDAV and CardDAV, and has added CalDAV support to its own Google Calendar cloud service.

Android still lacks support for either protocol however, leaving its users largely tied to Google's ad-supported cloud services. Because that's the core of Google's business model, Android is not likely to rapidly move toward embracing open standards for enterprise cloud services, nor greatly enhance its support for Exchange Server. As a hardware vendor, Apple has strong motivations to improve in both areas.

The next segment in this series will look at how Android offerings compare against iOS 4 in terms of the mobile carriers available.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

46 Comments

That's what I think is really interesting. My friend gave up his iPhone for the Nexus One and we've found that while I, with my iPhone, use about 1GB per month of data, because of Google's cloud service, he uses about 4-5 GB.

It seems as though if AT&T forced all of us to get rid of the unlimited plan, it would be Google users who are screwed, not *most* iPhone users.

As long as Apple charges for MobileMe the vast majority of people are not going to use it. I know lots of people with iPhones - some are Windows users, some have Macs - but none of them use MobileMe. The Google services, especially gmail, is extremely popular.

If you look at what Apple's doing, they are more interested in providing the software to access those "cloud" services than providing those services.

But if they have the software to access those services, they might one day be providing those services, you never know.

As long as Apple charges for MobileMe the vast majority of people are not going to use it. I know lots of people with iPhones - some are Windows users, some have Macs - but none of them use MobileMe. The Google services, especially gmail, is extremely popular.

All Apple has to do is role in the cost with the Telco.

That's what I think is really interesting. My friend gave up his iPhone for the Nexus One and we've found that while I, with my iPhone, use about 1GB per month of data, because of Google's cloud service, he uses about 4-5 GB.

It seems as though if AT&T forced all of us to get rid of the unlimited plan, it would be Google users who are screwed, not *most* iPhone users.

It's because of his own individual usage, not the cloud services. I don't think I even reach 1gb a month