Android, iOS apps skirt privacy policy to share user data with advertisers [u]

A report by the Wall Street Journal, part of a series examining privacy issues in computing and in particular the web, examined 101 popular smartphone apps for both iOS and Android devices to find what data they were sharing with advertisers.

The study found that more than half (56) sent the devices' unique serial number to advertisers for tracking purposes, while 47 made some use of users' location data. Five of the apps sent users' "age, gender or other personal details" to outside sources.

In some cases, this data is purposely entered by the user for reasons related to the apps' functionality, and some apps do outline that this data is also used for advertising purposes.

The Journal did not specify how it selected the apps that it tested or whether the roughly 50 apps on each platform represented a comparable selection, but it did note that "among the apps tested, the iPhone apps transmitted more data than the apps on phones using Google Inc.'s Android operating system."

The report also pointed out that not all apps were available for Android, including the company's own news app. "Because of the test's size," the report stated, "it's not known if the pattern holds among the hundreds of thousands of apps available." Apple lists over 300,000 apps for iOS devices, while Android's catalog of apps, ringtones and wallpapers is greater than 100,000 titles.

Mobile adware here to stay, hard to avoid

The findings might be news to some smartphone users, who are rarely presented with simple, straightforward information about individual apps' privacy policy. However, the use of unique device identifiers, location and demographic data to "enhance ad results" are have become core foundations of the mobile ad industry.

The report cited Michael Becker of the Mobile Marketing Association as saying, "in the world of mobile, there is no anonymity," and noting that the mobile phone is "always with us. It's always on."

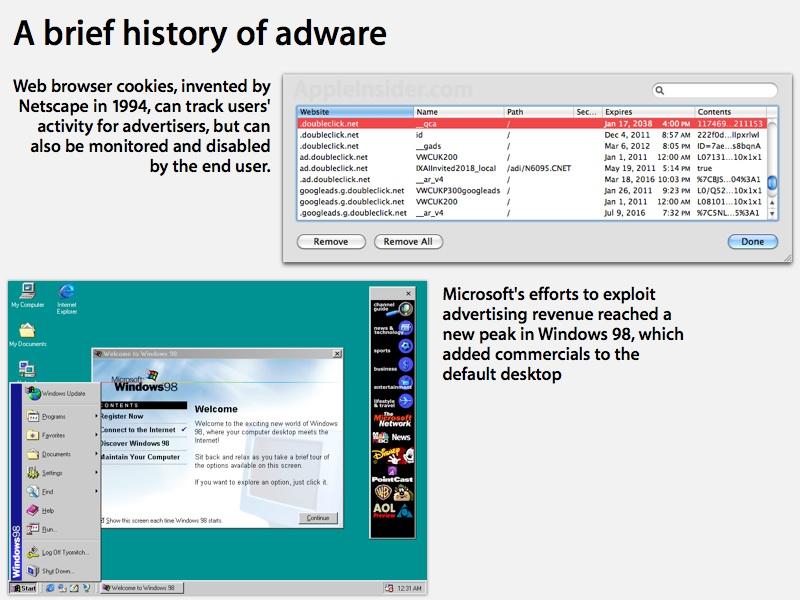

Unlike desktop computers, mobile devices such as smartphones don't generally allow users to delete individual cookies created by advertisers or install firewall security software that can block apps' requests to forward the users' personal data to outside companies.

The significant revenues tied to advertising are also pushing some vendors to relax individuals' privacy protections in order to maximize profits, a situation reflecting the history of adware on desktop PCs.

A history of adware

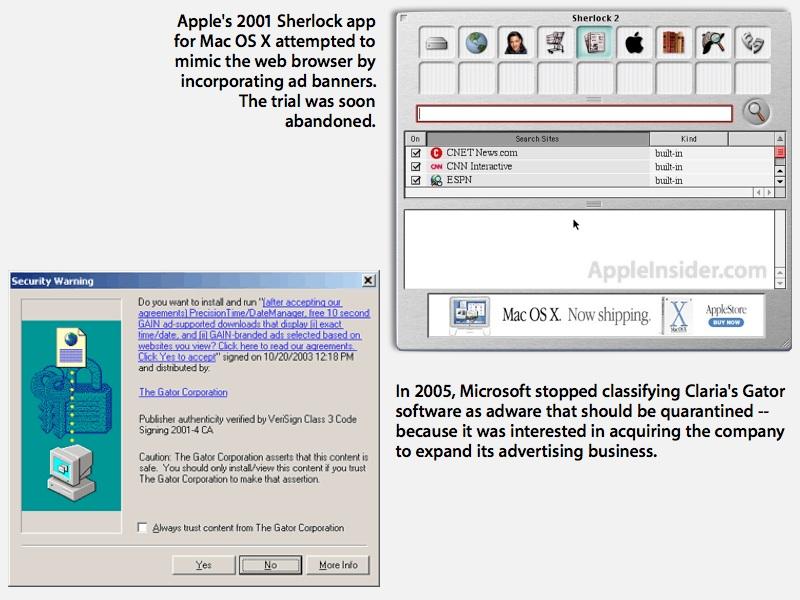

Adware began infecting PCs in the mid 90s, particularly as the web helped connect users to networks in a way that also made them easy to reach with ads. Platform vendors readily embraced the new avenues for revenues adware presented, with Netscape inventing web browser "cookies" as a way for web site owners to track visitors, while Microsoft's Windows 98 turned the PC desktop into an overt billboard for advertisers.

On page 2 of 3: Ads pop the web

In 2001, Apple jumped on the ad-supported software bandwagon by including web-like banner ads within Sherlock, its specialized search engine app for the web. That experiment didn't last long, and the company has since shunned ad banners within its desktop software.

Update: A reader notes: "Sherlock was a parallel searching technology, back in the days before Google you had to search more than one engine to get what you were looking for. With Sherlock you got all your results in one place without even opening your web browser.

"This of course would reduce the number of page views a search engine would get so Apple implemented that if you clicked on a result from a certain search engine, you would be delivered a banner ad from that search engine. If they hadn't most search engines would of blocked Apple from using their sites as they would get no advertising revenue and be unable to survive.

"Apple had their own search channel for searching the Apple.com website and Apple made up their own ads for it, but if you used Sherlock to search your hard drive (Sherlock was the find application for Mac OS 8.5 thru to Mac OS 9.2.2) there was no banner advertising or even a empty box, no ads were displayed on local search results."

Microsoft began bundling Alexa website tracking software on all new Windows PCs and in 2005 opened talks to acquire Claria, the vendor behind Gator, the web's most notorious adware trojan horse. While negotiating the acquisition, Microsoft silently removed Claria's products from the blacklist of malware that Windows AntiSpyware had previously recommended for quarantine.

However, a backlash against adware and spyware tactics began to gain momentum after a series of media reports brought public attention to web cookies and their ability to allow advertising companies to remotely track their activities on the web. Microsoft subsequently broke off talks with Claria as a new kind of subtle, contextual advertising, popularized by Google, fell into fashion as the public largely rejected the idea of being tracked by advertisers.

The controversial subject of user privacy continues to receive attention, with the White House issuing a memoranda this summer that "calls for transparent privacy policies, individual notice, and a careful analysis of the privacy implications whenever Federal agencies choose to use third-party technologies to engage with the public."

However, particularly since Google's acquisition of web cookie-centric ad vendor DoubleClick in 2008, online and mobile advertising has trended back towards user tracking rather than the kind of contextual relevancy Google pursued through most of the previous decade. Advertisers want to reach specific audiences, and the only way to do that effectively involves being able to track users by their demographic identity and by following their activities and location.

On page 3 of 3: iOS 4 attacked for limiting adware creep, Google fights for mobile adware

Recognizing the potential for mobile devices running third party software to exploit users' privacy, Apple has adopted an increasingly strict privacy policy for iOS, which forbids software makers from collecting private information, including location data, and using this for any purpose other than crafting anonymously relevant advertising. Additionally, Apple insists that app makers clearly disclose the information they collect; the company threatens to remove apps that fail to follow its policies.

As a mobile advertiser, Apple also has a privacy policy that it applies to its own platform. It enables users to opt-out of ads that use location data to refine their relevancy. In addition to opting out of iAd location-based ads, Apple also enables iOS users to turn off Location Services universally, or to switch off the ability of individual apps to request location data. Apps must also ask the user for permission to look up their location.

These efforts to protect users, which have not been duplicated by other mobile platforms, were targeted earlier this year in a report by David Sarno of the LA Times, which caused panic after it suggested Apple was tracking iPhone users' "precise" locations in some radical new way that other devices weren't, and incorrectly assumed that users were powerless to do anything about it.

In iOS 4, Apple enabled iAd and other independent ad networks to collect private information, but the company limits this data collection exclusively for use in improving ad relevance. Apple's SDK rules specifically forbid developers from including code in their apps that would forward private user information to third parties for any other reason, something the company's chief executive Steve Jobs characterized as granting users "freedom from programs that steal your private data."

Sarno's report resulted in a US Congressional inquiry into Apple's privacy policy, to which the company responded, "Apple does not share any interest-based or location-based information about individual customers, including the zip code calculated by the iAd server, with advertisers. Apple retains a record of each ad sent to a particular device in a separate iAd database, accessible only by Apple, to ensure that customers do not receive overly repetitive and/or duplicative ads for administrative purposes."

Google fights for mobile adware

Critics of Apple's privacy policy have claimed the company is trying to kill rival ad networks on the iOS platform by preventing other ad networks from harvesting users' private data, such as their GPS location, as they display ads within apps. Google's chief executive Eric Schmidt said Apple's ad restrictions were "discriminatory against other partners," including Google's own AdMob, which competes against Apple's iAd for mobile revenue.

Android does not appear to have any restrictions on the private user data that apps can forward to third parties. Google also does not have an app approval process like Apple's App Store. This has led to malware attacks from apps listed in the Android Market, which have destroyed users' data, installed adware and sent spam to contacts email accounts.

The lack of platform-wide privacy policy enforcement on Google's Android has also resulted in developers collecting inappropriate data, including users' phone numbers and potentially voicemail passwords, without users' knowledge or consent.

Known occurrences of the misuse of private data within Android apps are based on independent testing of individual apps, and is not exhaustive. Apps may reach widespread circulation for months before their actual activities are discovered, as there is no curation of Android Market provided by Google and there is nothing preventing the distribution of malware outside the official Android software store.

Google's Android platform is also more susceptible to pressure from adware proponents because a much greater percentage of Android software is ad-supported rather than purchased outright by the end user.

The developer behind "Angry Birds" noted that ad-supported software is "the Google way," and recent market data by Distimo indicates that Android's app catalog has roughly twice the number of free apps as other popular platforms, thanks to Google's policies promoting ad-supported software.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

66 Comments

Unbalanced as always .

You could also say on iOS there is no guarantee to know how the data is used.

There is just an obscure approval process... hope there are no flaws but nobody knows anyway.

On the other hand on Android you know exactly what kind of data the application is able to access when you install it.

So if one installs an application that wants location access but does not have any location based functionality its pretty obvious what the location access is for .

It's a lot more transparent than for example windows (Thinking about worms and address books).

Programs don't steal data; people do. And because private data are being gathered, unscrupulous people can still steal it, incompetent people can still leak it, and an ignorant, unwitting public can still give it up.

I wonder if Adobe Flash based cookies are used in Android?

If so does visiting a website containing Flash pop up a window asking for permission to install them and giving details of what they will be used for.

Or are Adobe and the companies that use them hoping that they will fly under the radar and be unnoticed and ignored as they were on PC's before their discovery buried deep in Adobe's applications folders.

Troubling.

This is how big companies go down. I'm not talking about scandal, but about contradicting priorities.

If all you have to worry about is making the best cellphone, then no worries. But if you're a huge company with many arms, then you have to make the best cellphone *subject to* it only playing the media from your media arm, and *subject to* having a UUID to keep your advertising arm happy, etc.

And then suddenly you wake up one day and your best is not *the* best, and some small, focussed company is making you look stupid.