2011 marks Apple's tenth anniversary of Mac OS X, iPod, Apple Retail

Ten years ago, Apple was facing tremendous uncertainty as the dotcom bubble burst, killing off liberal tech spending on high end products and hitting the company's core audience of creative designers particularly hard. To make matters worse, Apple had just launched its expensive new Power Mac G4 Cube in an attempt to cater to the demand for fashionable, high end gadgets just as that market was collapsing.

The doctom era had helped Apple solidly return to profitability beginning in 1998 following the $1.8 billion in losses it reported in 1996 and 1997, but the company was now faced with reporting a new quarterly loss of $195 million in January 2001.

However, the long term execution of a series of three major new initiatives launched later that year ensured the company wouldn't have to report another quarterly loss across the next decade, even when hit by a much greater global recession that stalled growth across the industry in 2008.

Mac OS X

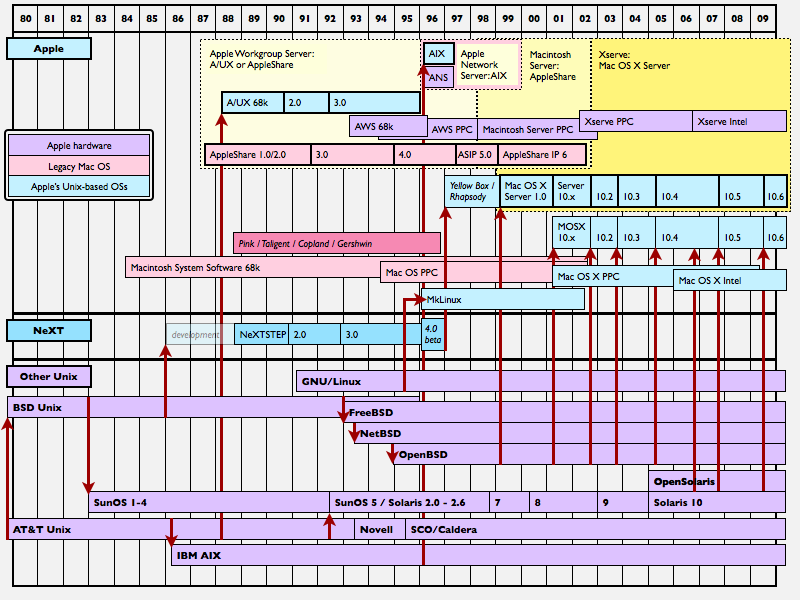

The first initiative was Mac OS X, Apple's new desktop operating system for Mac desktops, notebooks and servers. Mac OS X was based upon the NeXTSTEP technology it had acquired from Steve Jobs' NeXT, Inc. in the final days of 1996.

The company originally expected to quickly deploy NeXT's far superior OS, built upon a Unix foundation and offering advanced, object oriented development tools, to Mac users who currently running the ancient System 7. However, those hopes were dashed by the staunch resistance from major Mac developers including Adobe, Macromedia and Microsoft, who refused to spend the considerable resources needed to port their existing Mac apps to an entirely new system being offered by a company that, at the time, had a terrible record of delivering upon its software development roadmap and was struggling financially.

Without major modern apps, Mac hardware running NeXTSTEP would be hard to sell, given that Apple's existing customers wanted to retain their simple, familiar computing environment that could run their existing software, and the remains of NeXT's core audience had little interest in buying Apple hardware.

That forced the company to extend life support for System 7 while working to graft together NeXT's advanced technology and the valuable parts of Apple's existing software portfolio (its large Mac software library, QuickTime, and the familiar Mac user environment) into a new future product.

An ambitious project

That work took longer than planned, and the scope of the project kept expanding. Rather than making its next major Mac OS revision just a continuation of the existing Mac OS look and feel, Apple decided to take on the task of designing an entirely new graphical compositing engine to support the advanced graphics effects it needed to differentiate Mac OS X from the existing Mac OS and Microsoft's Windows, both of which used a relatively simple graphics system originating with the QuickDraw technology Apple had developed in the early 80s.

In March of 2001, Apple launched Mac OS X 10.0, the first major release of its new OS following its initial Public Beta of the previous fall. While loaded on new Macs, the new OS was not setup as the default boot system because it was noticeably slower than Mac OS 9 and offered few obvious advantages, given the lack of native software available.

In September, Apple followed up with a free 10.1 release that addressed performance and glaring omissions, including the ability to play DVDs. By the next summer, Apple was ready to stage a mock funeral for Mac OS 9, telling its Mac developers at WWDC that Mac OS X was the future. A series of attractive hardware releases, including the thin new 2001 Titanium PowerBook, 2002's distinctive iMac G4 and 2003's Power Mac G5 (the first mainstream 64-bit personal computer) helped Apple to attract new users to Macs years after many pundits had dismissed the platform.

Key to Apple's survival

The development of Mac OS X was a critical factor in Apple's resurgence. It established that the company could deliver upon its software roadmap, an important accomplishment given the company's failure to radically modernize System 7 throughout the 90s in a series of boondoggles and vaporware known as Taligent, Copland and Gershwin.

Mac OS X would later enable Apple to rapidly transition the Macintosh and its third party software to Intel in 2006 (something that would have been impossibly difficult to pull off with the old classic Mac OS). It also provided Apple with the ability to deliver a mobile version capable of using the same development tools in 2007's iOS, and set up the company to provide a strong alternative to Microsoft's Windows, which didn't attempt to deliver a similarly advanced graphics compositing engine until Windows Vista's release in 2007. There would be no modern Apple today without Mac OS X.

Later this year, Apple will release its seventh major reference release in Mac OS X 10.7 Lion, which the company says will advance many of the concepts present in its mobile variant, iOS 4. Prior to that happening, the company has announced that it will open the Mac App Store on January 6, which will bring iOS-style direct software shopping, downloads, and updates to desktop Mac OS X users.

On page 2 of 3: iPod

Apple's success with the Mac OS X platform was also tied to the release of the iPod in 2001, which dramatically turned around the public perception of the company. Ten years ago this month, Apple launched iTunes, a free software release built around Casady & Greenes' SoundJam MP music jukebox app, which Apple had acquired the previous year.

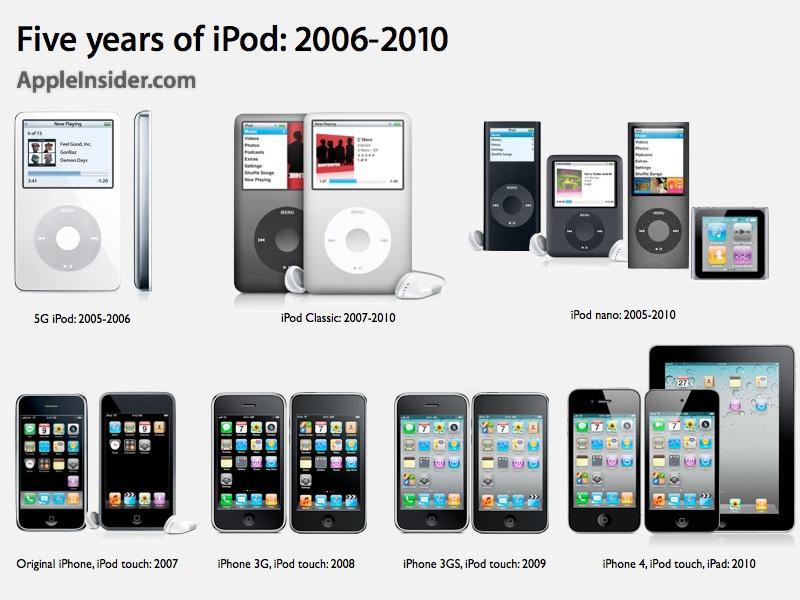

The strategy behind Apple's release of iTunes became clearer in October of that year, when the company launched the iPod, a 5 or 10GB music player capable of holding a large library of a thousand MP3s.

While hard-drive MP3 players were not new, the combination of Apple's easy to use iTunes software for cataloging and syncing music on a desktop computer, paired with the iPod's fast FireWire interface and simple operation made the new player unique, and ultimately popular. The iPod also benefitted from its use of Toshiba's new 1.8 inch hard drive mechanism, which allowed the device to be small and sleek, with enough room for a battery supporting all day use.

Competing products typically used very slow USB 1.0 or serial connections, which made music sync lengthy and clumsy. Few were bundled with easy to use software, and many expected users to navigate complex menus on the device to organize or even play their music. Few alternatives offered the thin, small package of the iPod, being based instead around larger 2.5 inch laptop drives.

Apple had quickly brought the iPod to market, using an existing reference design created by PortalPlayer based upon two ARM processors and a custom interface developed under contract by Pixo. The original iPod models offered a nod to the Macintosh with its use of the same Chicago font that had originally been the Mac's default system font.

The iPod phenomenon

Sales of the first year of iPods only amounted to 376,000 units, but helped pad the company's balance sheet because the new devices were profitable. In its second year, Apple expanded beyond the Mac to begin selling iPods to Windows users, initially pairing it with MusicMatch software. The company subsequently sold nearly a million iPods in fiscal 2003. The following year, the company sold 4.4 million, indicating Apple had discovered a true hit. The company was now selling more iPods than Macs.

The iPod franchise branched out with the even smaller iPod mini in 2004, which offered a cheaper, thinner 1 inch microdrive-based option that could compete against smaller flash capacity MP3 players in cost and capacity. In fiscal 2005, the iPod exploded, with sales reaching 22.5 million units, thanks to the low cost new iPod shuffle and the thin new iPod nano, both of which used Flash RAM for storage rather than a mechanical hard drive.

Since 2005, Apple's pace of development with the iPod has increased dramatically, expanding the product category into smartphones with the iPhone and tablets with iPad. A look at the company's progress over the last five years was recently featured in the articleFive years of Apple: 2005 iPod to 2010 iPod touch.

Combined with rapid expansion of iTunes, including 2004's new iTunes Music Store, the iPod became a cultural phenomenon that competitors were incapable of duplicating. Apple's iPod was particularly embarrassing to Sony, which had long reigned as the top name in portable music players with the Walkman. Microsoft was also stymied in its attempt to create a Windows-like licensing model called PlaysForSure, which intended to compete against the iPod using partnerships with hardware makers and independent music stores.

Key to Apple's survival

iPod sales grew rapidly through 2007, when Apple began selling the iPhone and iPod touch as an entirely new mobile platform that leveraged the brand recognition and economies of sale of the iPod along with the technical capabilities of Mac OS X. Without the financial contribution of its iPod sales, Apple may not have survived through the decade as it struggled to sell Macs to an audience that had long associated it with an underdog, alternative niche. The iPod restored Apple as a popular, mainstream brand and earned it respect as a competent product developer and savvy marketer.

Massive global sales volumes of iPods also established Apple as the world's largest consumer of RAM, enabling it to negotiate favorable contracts with producers. Apple leveraged its economies of scale with the iPod to deliver 2007's 8GB iPhone with an unprecedented amount of storage for a smartphone at a time when competitors were only including 128MB or less of storage. More recently, the company has flexed its market power in RAM procurement to bring SSD drives to the mass market with the MacBook Air.

On page 3 of 3: Retail Stores

Apple's ability to sell both Mac OS X and the iPod were tied to a third development that turns ten years old this year: Apple Retail. Throughout the 90s, Apple experienced a significant disadvantage in trying to sell its premium computers through retailers who could far more easily push cheap PC systems that relied exclusively upon price to clinch the sale. Many retailers were also able to make more money assembling their own house brand PCs, and could make even more money selling service and support for them.

Early computers had been sold through specialty stores with knowledgeable sales reps, but as computers went mass market in the early and mid 90s, big box retailers and department stores took over much of the volume of computer sales, leaving customers to make complex purchasing decisions largely on their own, looking at little more than a price tag and a confusing list of hardware specifications.

After leaving Apple to found NeXT in 1985, Steve Jobs had hoped to create a series of boutique retail stores to sell users on the advantages of higher quality, better designed computers. However, NeXT lacked the retail savvy and resources to build out a significant retail presence, and instead ended up abandoning its hardware sales in 1993 in hopes of selling its software to enterprise customers who better appreciated its value compared to Windows.

Apple experienced the same set of problems as NeXT in trying to sell buyers a more sophisticated product with advantages that were not always readily apparent in simplistic feature checklists or hardware specification lists. Neither company could rely upon third parties to sell their products for them; they both needed a retail presence to compete against generic PCs.

Apple's retail aspirations

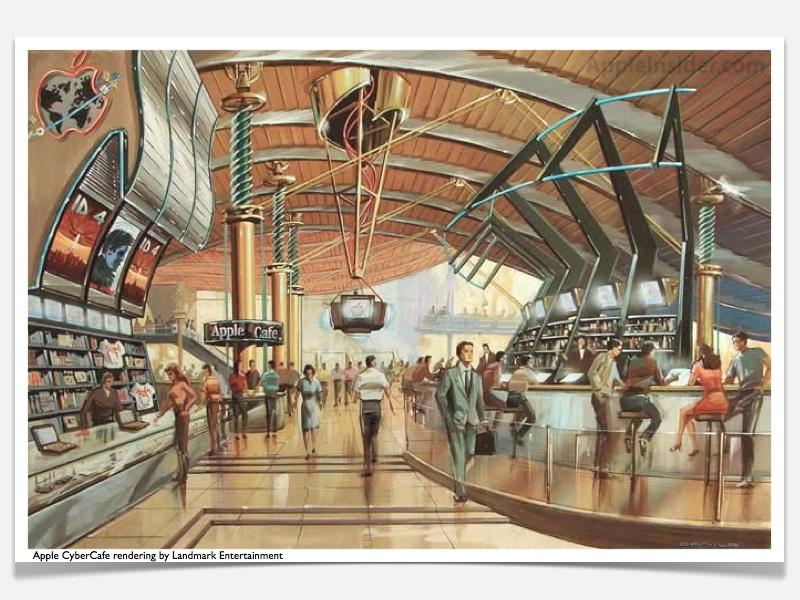

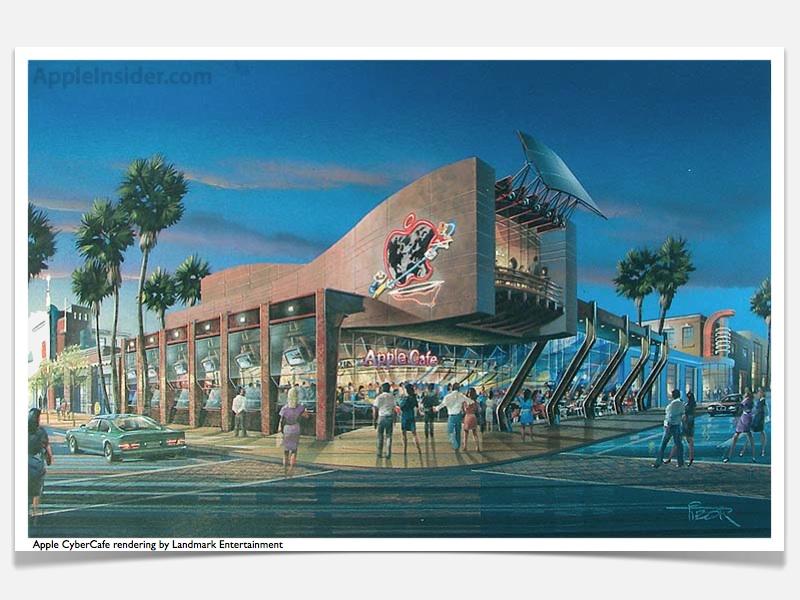

In 1996, Apple announced plans to reach consumers by building a chain of "cybercafes" that would feature the company's products, allowing users to surf the web and play games while drinking coffee and eating food.

The company partnered with Landmark Entertainment, which had been building minor theme park-like attractions including the Star Trek Experience in Las Vegas and a Jurassic Park attraction at Universal Studios. The first stores were supposed to be built by late 1997, starting with a 15,000 square foot store located in Los Angeles and expanding to London, Paris, New York, Tokyo, and Sydney, Australia.

A year later, Apple confirmed that it had shelved its cybercafe plans, apparently blaming Landmark for the lack of progress. Apple had registered the AppleCafe.com domain and promoted the new cybercafes as "coming soon" on its website.

Jobs targets Dell via the web

In place of the cybercafe partnership, Apple devoted its attention to its own internal retail efforts on the web itself, launching an online Apple Store in late 1997 in conjunction with a simplified new line of Macs using G3 processors. The store was built using the WebObjects server technology that Apple had acquired along with NeXT less than a year earlier. It enabled customers to build custom PowerMac configurations online for the first time.

Jobs' NeXT had previously worked with Dell to build its online retail operation, but after being acquired by Apple, Dell quickly scrambled to rid itself of WebObjects. Its chief executive Michael Dell had told a Gartner Symposium audience that summer that, were he in charge of Apple, he'd “shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders.â€

In launching Apple's new online store that fall, Jobs announced Apple would instead be targeting Dell, saying, "with our new products and our new store and our new build-to-order, we're coming after you, buddy."

An ambitious project

Apple was also painfully aware of its dysfunctional relationships with brick and mortar retailers, including Sears, Best Buy, Circuit City, Computer City and Office Max. Apple's Macs sat, frequently off and collecting dust, while retailers continued to promote cheap generic PC and their own assembled machines. Alongside its online efforts, Apple announced a new retail program with CompUSA in late 1997 that created a "store within a store" area devoted to Apple products in each of the chain's 140 US outlets, each staffed with Mac-savvy employees who were paid by Apple.

Less than two years later, Jobs recruited Millard 'Mickey' Drexler, CEO of the Gap and later J. Crew, to Apple's board, as Apple began work to assemble its own team of retail, development, and real estate experts pursuant to building out its own retail stores. Apple subsequently hired Ron Johnson, a vice president of merchandising at Target, as its senior vice president of retail operations; George Blankenship from the Gap as its vice president of real estate; Kathie Calcidise as its vice president of retail operations; and Sony’s Allen Moyer as its vice president of development.

Between 1997 and 2000, Apple slashed the number of third party retail outlets that were selling Macs from 20,000 to 11,000. In 1998, Apple's chief of operations Tim Cook explained that the company needed to “cut some channel partners that may not be providing the buying experience [Apple expects]. We're not happy with everybody."

Facing the dotcom crash and the economic downturn that affected most retailers in 2000, Apple decided to pulled its products out of Sears, Best Buy, Circuit City, Computer City and Office Max entirely to focus all of its retail efforts with its CompUSA "stores with a store." Apple later returned to Sears, only to pull out again in 2001. Apple also ended its shaky retail partnership with Circuit City in 2001.

Apple opens stores

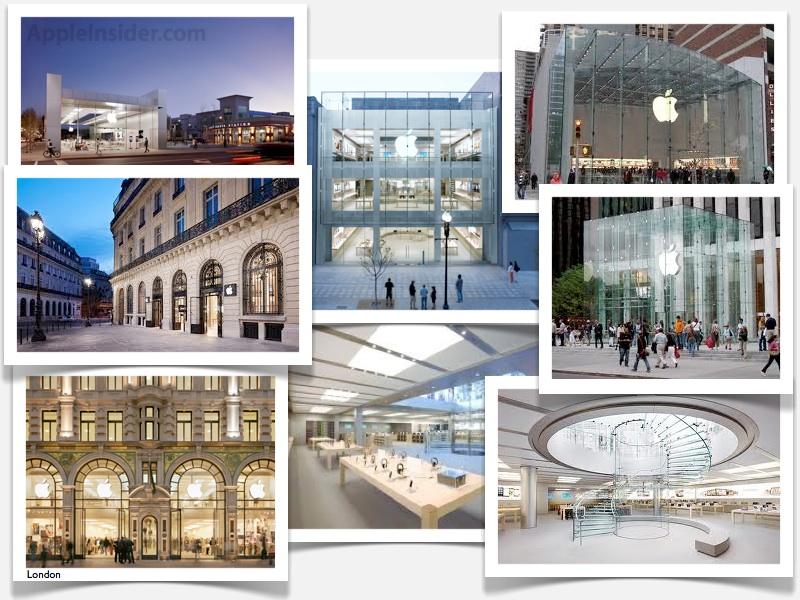

In May of 2001, Apple began opening its first retail stores, rejecting the trend toward efficient big box retail and instead working with architects and interior designers to craft smaller boutique stores featuring flourishes including hardwood floors, glass stairways, presentation theaters and a Genius Bar providing technical support. The new stores also featured lots of usable Macs and iPods customers could try out in the store.

Apple's success in retail wasn't universally anticipated. The May 2001 MacWorld article "Apple Stores: Sale of the Century?" quoted consultant David Goldstein of Channel Marketing Corp. as saying of Apple, "it makes absolutely no sense whatsoever for them to open retail stores."

Goldstein complained that Apple's retail strategy wasn't going to work because consumers 'haven't indicated that they're having trouble finding outlets that sell Macs,' stating that "It's another case of Apple being Jobs driven and not consumer driven."

Goldstein also wrote his own article entitled, "Sorry, Steve: Here's Why Apple Stores Won't Work," where he said, "I give them two years before they're turning out the lights on a very painful and expensive mistake."

Apple was entering retail just as Gateway was abandoning its failed efforts to transition from a mail-order company to a retail chain. The most successful PC makers were Dell and HP, both of which relied up on third party retailers and direct sales, rather than trying to sell their products in their own stores. Goldstein's criticism of Apple's retail efforts were not unique.

Apple's stores also generated some controversy by shifting the company's attention from its old dealer network to the new retail operations that Apple maintained full control over and could change at will in reaction to what worked and what didn't.

Key to Apple's survival

The company's retail operations rapidly expanded, with 27 opening in 2001, followed by another 23 in 2002, and 22 more in 2003 when Apple expanded beyond the US to open its first stores in Japan. New international stores in the UK were among the 27 spots to open in 2004. Another 34 stores opened in 2005, including the first in Canada. Another 34 opened in 2006, 33 in 2007 expanded Apple's reach to Italy, while 46 opened in 2008, including the first in Germany, Switzerland, China and Australia. New stores in France were among the the 51 opened in 2009 and 39 more in 2010 expanded Apple's retail presence to Spain.

There are now 332 Apple Retail stores, including flagship location in Boston, New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, Tokyo, Osaka, London, Sydney, Perth, Montreal, Munich, Zurich, Paris, Beijing, Glasgow, Honolulu and Shanghai. Rather than just being an expensive way for Apple to reach consumers, the company's retail stores have earned top profits far higher than competing retail stores of any kind.

Apple's retail operations didn't just help keep the company afloat as a source of revenue either. They also served as a distributed convention center, allowing Apple to host events and launch products. Apple cited its retail store traffic as the reason it pulled out of Macworld Expo, and in 2007 Jobs told a Forbes journalist, "Our stores were conceived and built for this moment in time - to roll out iPhone."

Without highly trafficked retail stores in prime shopping locations, Apple would have found it far harder to ship impressive volumes of iPods every winter, or draw highly publicized launch crowds as it did with the last four generations of iPhone and with the iPad. It would also not have seen the sharp uptick in quarterly Mac sales, which have jumped from 659,000 in the first quarter of 2001 to 3.89 million in the company's last reported quarter.

Along with those new Macs, Apple sold over 9 million iPods, more than 14 million iPhones, and 4.2 million iPads. Even the new Apple TV has launched to sales of more than a million in its first quarter. Ten years ago, none of those other products even existed, but today they account for more than 30 million units per quarter for a company that a decade ago was struggling to sell less than a million per quarter.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

22 Comments

Cool, first to post.

Thanks Daniel, always good to read your articles.

All I can say is this, thank you Apple, for without you, using a computer or mobile device would certainly be a drag.

May 2011 be even more successful.

Cool, first to post.

Thanks Daniel, always good to read your articles.

All I can say is this, thank you Apple, for without you, using a computer or mobile device would certainly be a drag.

May 2011 be even more successful.

With great power, comes great responsibility.

May 2011 be ginormic. But, may Apple shore up

the tripfalls along the way.

~Yes, much artistic linguistic license used in this post~

Thanks Daniel for another enjoyable trip down memory lane of what was one epic decade for Apple...

And if it was epic, we'll need to find another word entirely to describe the next one, which will see Apple reaping it's just rewards for its innovations - that made others look like their boots have been stuck in treacle!

Happy New Year to one and all..

Great article, Daniel. I, like many others, started my Apple path when I couldn't get iTunes to work on my old Dell. The user experience was like night and day. No viruses, no need to defrag, no crashes. Apple offers a simple user experience yet offers advanced technology. Here's to the next 10 years.

"System 7"? Don't you mean to say "MacOS 9"?