Four years after introducing Touch ID to radically enhance iOS users' privacy and security, today's Apple is doing exactly what Steve Jobs would do — phasing it out and moving on to something even better: Face ID technology in iPhone X.

Figure out what's next

There's a Jobs quote that adorns the wall across from the Apple's Town Hall Theater at 4 Infinite Loop: "When you do something and it turns out pretty good, then you should go do something else wonderful, not dwell on it for too long. Just figure out what's next."

This week, Apple literally moved on by holding its iPhone X event at Apple Park in the freshly finished Steve Jobs Theater, a venue that's larger, greener, more comfortable, architecturally dazzling and outfitted with a spectacular 4K projection system, among many of its other technical, logistical and aesthetic enhancements.

Apple also moved on metaphorically in deconstructing the product that has served as its record shattering cash cow — the iPhone that Jobs himself first introduced back in 2007 — and reimagining it fresh from the ground up.

The very iconic representation of iPhone (a rectangle with a round Home button) has now made way for a new one featuring little more than a slim bezel with a notch on one end. More importantly, the defining role of the physical Home button has disappeared, and rather than being virtualized in software it has been thrown away entirely.

All of the layers of functionality previously mapped on the Home button have been rethought, from returning to the Home screen to switching apps to invoking Apple Pay to taking a screen shot and unlocking the device via Touch ID.

iPhone X represents the most bold rethinking of Apple's entire platform computing since iOS itself. However, the primary shift that has trigged the most fear, uncertainty and doubt in the iPhone X transition is the move away from Touch ID — something that didn't even exist across the first five generations of iPhone.

iPhone 5s introduces Touch ID

Similar to the new Face ID of iPhone X, Touch ID was first introduced on iPhone 5s, the fancier model of two parallel new iPhone releases (the less expensive iPhone 5c didn't have it). At the time it was widely expected that the lower priced 5c would drive iPhone sales, following the industry trend toward lower priced smartphones.

Instead, even Apple's internal forecasts were upended by the record-setting surge in demand for the premium iPhone 5s, clearly driven in large part by Touch ID.

This was noteworthy because the 5s faced significant competition from rival phone makers with attractive, marketable features including larger 5.7" screens, higher resolution 1080p displays, faster 4G LTE data service, stereo speakers, optical image stabilization, waterproofing and Qi charging. Previously, fingerprint sensors on Android phones had been flops.

iPhone 5s went on sale alongside a variety of phones that the tech media had lavished praised upon in 2013, including the HTC One, Google's Nexus 5, Moto X, Nokia's LUMIA 1020 Windows Phone, Samsung's Galaxy S4 and Sony's Xperia Z1. iPhone 5s beat them all despite lacking their fancy features.

It helped that Apple also had its fresh new iOS 7 and all the advantages of the iOS App Store ecosystem, but those features also helped the cheaper 5c — which also beat Windows and Android flagships. However, Touch ID (and the A7 chip that enabled it) were the primary sales drivers of iPhone 5s, which distantly outsold the cheaper 5c.

The world before Touch ID

Prior to the release of iPhone 5s in 2013, if you wanted to secure your phone you needed to lock it with a passcode. However, less than half of users actually used a passcode at all, because entering it every time you wanted to unlock your phone was a major inconvenience.

At WWDC 2014, Apple announced that its new Touch ID had radically increased passcode security among iPhone users, with adoption climbing from 49 percent to 83 percent.

It's incredible to think that just a few years ago most people were not bothering to use a passcode at all (while a large segment of users who did have a passcode likely configured it rather loosely). Without a passcode, anyone who took possession of your phone could look through your photos, open emails, and essentially take over your digital life by discovering and resetting various passwords via SMS or email.

Touch ID was adopted so rapidly because Apple implemented the technology in a way that made it almost effortless to use. When Samsung, HTC and others later tried to copy Apple's work, they introduced glaring security issues that did things like save an unencrypted photo of the user's fingerprints to the filesystem as world-readable (without setting any file permissions) so that any process could easily read and extract the data.

Samsung Galaxy S5 claimed a fingerprint sensor "just like iPhone," except that it was slow and didn't secure users' prints or data

Apple didn't just slap on a fingerprint reader; it developed and publicly detailed its comprehensive privacy policy and security architecture that ensured that no apps on the phone could access any biometric data. This required a special Secure Enclave environment built into the A7 chip that iOS and its apps could not read. Once configured, the OS could only verify that the enrolled user was present, not collect or store biometric data.

Apple invested significant resources into getting Touch ID right because it had more in mind than just securing iPhones with an easy to verify fingerprint. The company also intended to use Touch ID to launch Apple Pay and make an authentication system that third party apps could use, but not abuse.

Touch ID panic: This all happened before

At the introduction of Touch ID, there was widespread disbelief and rather histrionic sensationalism attacking Apple's ability to secure its users. One fingerprint expert, Geppy Parziale, claimed Touch ID couldn't possibly work well before it was even released, insisting that the sensor could not stand up to repeated use and that once it failed it would allow access to the device.

Immediately after Touch ID launched, U.S. Senator Al Franken wrote Apple asking for answers to a series of questions, including whether Apple collected, stored, transmitted, backed up or otherwise shared users' fingerprint data in a way that would enable malicious users to assume their identity, given that individuals can't change their fingerprints once they are stolen.

Hackers claimed to bypass the system using fake fingerprint models laser printed and modeled in a lab using a high resolution scan of a person's fingerprints, although Touch ID only offers a narrow 48-hour window and five authentication attempts before it turns itself off.Touch ID insanity continued for months, only dying out after it became incontrovertible that Touch ID was drastically increasing real world security and even contributing to a notable decrease in thefts, thanks to Apple's iOS 7 Activation Lock feature tied to the increased use of passcode security.

There were also concerns about what happens if you injure your finger, what if thieves cut your fingers off as they steal your phone, or what if you are the rare case of being born without fingerprints?

Touch ID insanity continued for months, only dying out after it became incontrovertible that Touch ID was drastically increasing real world security and even contributing to a notable decrease in thefts, thanks to Apple's iOS 7 Activation Lock feature tied to the increased use of passcode security.

When competitors introduced their own fingerprint systems — even with massive, sloppy security flaws like those by HTC and Samsung — there was no handwringing rage left. MasterCard recently launched a fingerprint credit card with none of Apple's strong security policies and nobody in the media cared.

Touch ID insanity was a contrived lie created to sell sensationalized panic, cultivated by some of the same sources who have repeatedly publicized, advanced and fanned the flames of fictions and hogwash from AntennaGate to BendGate. They conspicuously lose interest in the story as soon as they realize its not having any impact on Apple's business.

Across the last four years of Touch ID, Apple enhanced its speed, expanded its functionality to Apple Pay and then converted it into a solid state sensor with no moving parts to facilitate water resistance on iPhone 7. This year, Apple introduced the technology it developed to replace it, with Face ID on iPhone X.

New Face ID...

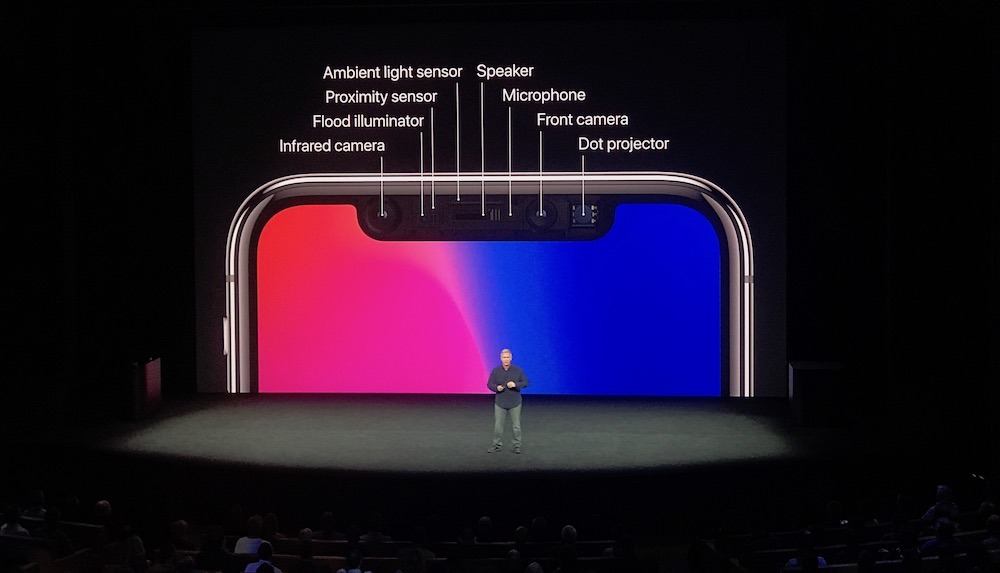

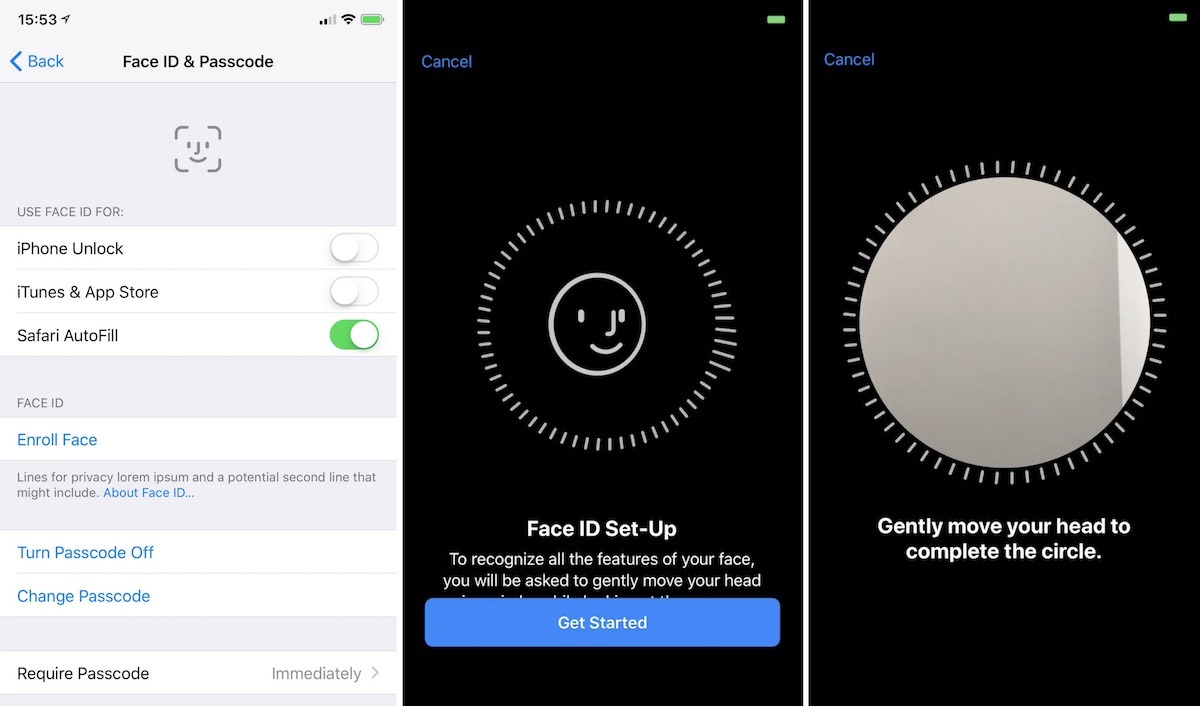

Rather than optically scanning fingerprint patterns on the Home button, iPhone X's TrueDepth sensor uses a 3D structure sensor to image the contours of a user's face using light in the invisible spectrum. That data is then processed by the neural engine in the new A11 Bionic chip to authenticate the user, without regard for facial hair, glasses, hats or other details.

At its hands-on demonstration area, Apple showed the rapid facial recognition iPhone X performs when a user looks at the device. Authentication occurs rapidly, unlocking the device to show recent notifications and allowing the user to swipe up to begin using apps. Apple Pay, triggered by tapping the side button, similarly performs a rapid Face ID check.

Scanning your face has a variety of advantages over scanning a fingerprint: Face ID claims a one in a million match rate, compared to fingerprint scans with a match rate closer to 1 in 50,000. The user also has to attentively look at the device, making it far harder to surreptitiously unlock the phone of a passed-out person than Touch ID.

As with Touch ID, iOS 11 now makes it easy to disable biometric authentication when you tap the side button five times in a sequence. So in situations where you don't want Face ID to work, you can easily force iPhone X to require your passcode. It also turns itself off after two false attempts, or whenever the device is turned off.

Apple's been working for years on both the underlying security model of iOS and the structure sensor 3D scanning technology it acquired from PrimeSense back in 2013 — when Touch ID was brand new.

Just as other vendors had worked with AuthenTech on fingerprint scanners before Apple acquired that company to build Touch ID, Google, Microsoft, Qualcomm and others had all previously built technology related to the PrimeSense 3D structure sensor, but none managed to drive down its cost and expand its functionality into practical applications the way Apple has.

Apple's 3D technology portfolio used to develop iPhone X and its TrueDepth system used for Face ID included the AR team at Metaio and motion capture firm Faceshift, both acquired in 2015, and Emotient facial expression recognition early last year.

The company has also snapped up a series of artificial intelligence and machine learning companies, resulting in a hyper-specialized team that's delivered not just Face ID, but also the new iOS ARKit and Vision frameworks and apps from Animoji to the platform for building the 3D AR filters demonstrated for Snapchat at Apple's event.

Same Old Panic!

Predictably, critics have sprung into action to suggest to their audiences that Face ID can't possibly actually work (spoiler, yes it does).

Senator Franken again wrote Apple to ask whether it collects and sells data related to users' faces, and whether it has considered the diverse spectrum of facial features in its machine learning models for recognition.

A report published by Luke Graham for CNBC grieved "Apple's Face ID security technology may not prove popular with consumers," based upon a survey where 40 percent of those asked agreed with the idea that biometrics were "too risky and unknown" to use.

However, 30 percent of respondents had never even heard of using biometrics to verify identity and another 55 percent said they'd heard of biometrics but said they hadn't ever used it.

The survey discussed biometrics related to shopping, not specifically Apple's new Face ID (which was added for clickbait). However, Touch ID is also biometric authentication, and it's really unlikely that the PaySafe survey of UK, US and Canadian consumers managed to find a group of over 3,000 people of whom half had never used Touch ID an iPhone over the last four years. It seems more like they were literally coaxed into being afraid of something they had been doing every day without thinking about it.

Ron Amadeo wrote an entire article for Ars Technica declaring that Face ID "is going to suck," although by the eleventh paragraph he acknowledged, "I will admit I have not tried Face ID yet," before explaining, "it's hard to imagine a facial recognition system that solves the problem of having to carefully aim a phone at your face."

The Face ID future

While there's plenty of concerns being voiced about how terrible it will be to have to glance at your iPhone to unlock it before you look at the screen to use it (sounds like flawgic), the reality is that Face ID not only does what Touch ID did, but also can handle new things like keeping your phone awake as you read.

And of course, the biggest benefit of getting rid of the Home button is that the bezel can shrink away, delivering a larger screen in a more compact phone.

Previously, we noted that Apple's premium priced iPhone X enables the company to launch advanced new technologies to a smaller, exclusive audience.

FWIW, talked to several supply chain contacts and heard range of 40-50m iPhone X inventory planned for 2H 2017.

— Ben Bajarin (@BenBajarin) September 13, 2017

However, according to analyst Ben Bajarin of Creative Strategies, Apple's suppliers are gearing up to build 40-50 million iPhone X units by the end of this calendar year. That suggests a very large mix (half!) of holiday quarter iPhone sales will be iPhone X, and implies a very solid base of iPhone X users within just two months of sales.

Such a huge number of Face ID users mean third party developers will have good reason to work to exploit its TrueDepth sensor, creating new ways to put its enabling hardware to work. And of course, Face ID automatically works in apps designed to currently authenticate with Touch ID.

It looks like Face ID is what's next.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

76 Comments

My biggest query is when the phone is sitting on the desk, right now I just press with my finger and get a quick sense if any messages have arrived. With face ID I will either have to lean over or lift the phone, not optional. And, realize this is the true definition of a 1st world issue.