With days until the launch of the iPhone X and its Face ID camera array, Microsoft's own motion sensing and facial recognition system for Xbox, dubbed Kinect, has been officially discontinued after a long period of languish. AppleInsider explains how Apple and Microsoft's separate facial recognition technologies — one failed, one upcoming — both share common roots.

Kinect first debuted as an optional accessory for the Xbox 360 in the fall of 2010, amid a wave of motion-controlled gaming hype. The camera and microphone system found initial success, but quickly faltered as the technical limitations of the device became apparent in gameplay.

For Apple fans, Microsoft's first Kinect for Xbox 360 is noteworthy because it was based on technology licensed from an Israeli company called PrimeSense. Apple eventually bought PrimeSense for $345 million in late 2013, paving the way for the Face ID technology that will debut next Friday in the iPhone X.

After the first Kinect lost steam, Microsoft went with different — and more expensive — technology for Kinect 2.0. That resulted in the next-generation Xbox One launching with a high $500 price tag — $100 more than its primary competitor, Sony's PlayStation 4.

With sales struggling, Microsoft looked to reduce costs on the Xbox One, and began selling it without the Kinect sensor. Support for the accessory quickly became nonexistent.

This week, Microsoft confirmed to Fast Company that it has ceased manufacturing of the Kinect hardware entirely. Given the lack of Kinect support on Xbox One, it's not surprising.

It is a rather tremendous fall from grace for the Kinect platform, which had the ability to track motion, understand a user's voice, and recognize their face. Developers hacked it to scan objects and entire rooms in 3D, and Microsoft promised that future updates would be able to distinguish fingertips and understand complex hand movements like sign language.

The technology's initial promise would ultimately go unfulfilled — at least in Microsoft's hands.

Apple saw value in the same technology, but took a different approach

In many ways, Microsoft was ahead of its time in the pursuit of motion sensing and facial recognition technology. But the company applied that technology in in rather simple ways, with a focus on gaming and entertainment.

An Xbox One paired with Kinect will still identify individual users when they step in front of the TV. But it's a mere convenience, and certainly not a reliable security method.

Interestingly, when Apple bought PrimeSense, many onlookers speculated that Apple would follow in Microsoft's footsteps and release facial and motion recognition technology for a future Apple TV update.

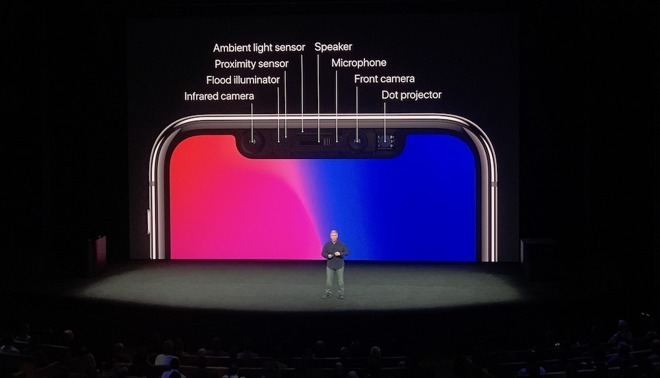

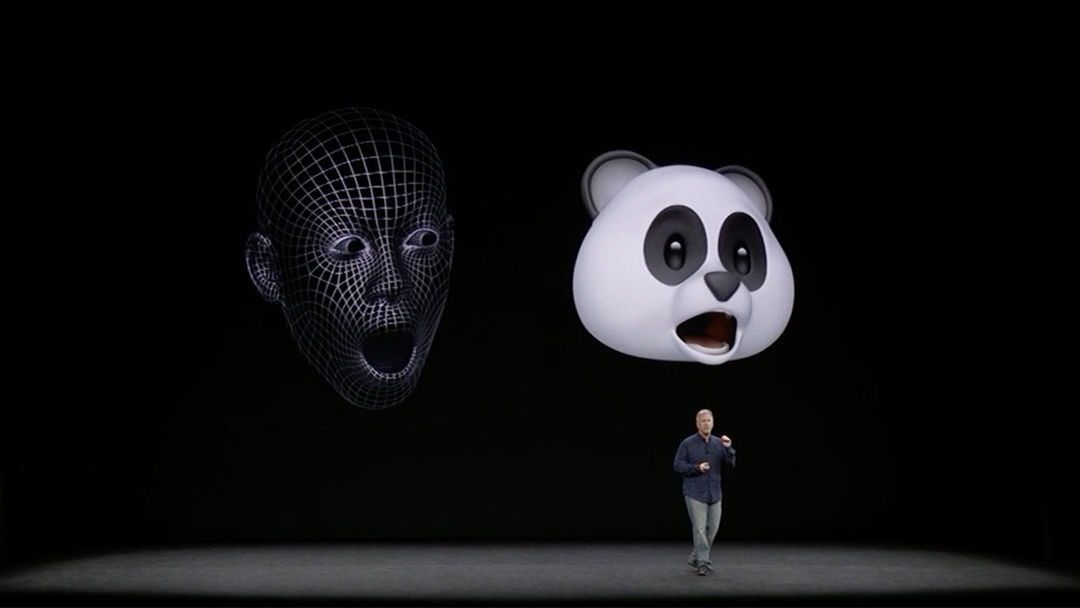

It turned out that Apple had very different plans, seeing the miniaturization of the same technology as the future. The purchase of PrimeSense proved to be part of Apple's push to replace Touch ID with Face ID and TrueDepth.

While Kinect can recognize a user, greet them, and track their hand movements, it never found much utility beyond casual games. In particular, the motion tracking was occasionally unresponsive and frequently lacking in precision, meaning traditional gamers preferred to stick to reliable physical controllers.

Dedicated console gamers — a sizable but still niche group — saw the Kinect as a gimmick. It was a subset of a subset of a market.

Apple's far tinier and far more capable Face ID offers a more essential function — its TrueDepth camera system is the primary security point for a device millions of users will turn to countless times per day: the flagship iPhone X. By scanning a user's face in 3D, in much the same way that Kinect could scan an entire room, the iPhone X can securely identify a user with accuracy greater than Touch ID.

Though they share common roots, Kinect and Face ID are not a simple comparison. Apple, of course, has had the advantage of time, given how far technology has advanced since that first Kinect launched in 2010. And access to Face ID carries a starting price of $999 for the entry-level iPhone X, far more than Microsoft has ever charged for any Xbox model or its accessories.

Microsoft sold 24 million of the first PrimeSense-powered Kinect by February of 2013, a little over two years after it launched.

Given the sales history of new iPhone models, Apple could very well exceed that number with the iPhone X in just its first two months — provided the company can keep up with consumer demand.

Microsoft's investment in Kinect was not for nothing — it lives on in other ways, including Cortana, its voice-driven personal assistant that competes with Apple's Siri. The core sensor also powers Microsoft's Hololens augmented reality headset, which remains developer-only for the time being.

Ships passing in the night

The strange saga of Apple and Microsoft crossing paths, with one entering a market while its rival exits, is not new.

Most notably, Microsoft began to push its Zune media player as a threat to the iPod in November of 2006, only a few months before Apple unveiled the first iPhone. While Microsoft was desperate to chase Apple's success in portable media players, Apple was instead busy skating to where the puck would be.

History has not treated the Zune kindly, seeing Microsoft's attempt as completely lacking in vision. The Zune was unceremoniously killed a few short years after it debuted.

Instead of being late, Microsoft was ahead of the game with its pursuit of touchscreen devices, including early smartphones and tablets, throughout the 2000s.

However, Microsoft focused on stylus input and handwriting recognition, or gimmicks like the original table-sized Surface computer, which failed to gain traction with consumers in meaningful ways.

Apple, meanwhile, took a slow and steady approach, waiting for capacitive, finger-friendly touchscreen technology to get smaller and more affordable. Its debut of the first iPhone in 2007, followed by the iPad in 2010, caught Microsoft flat-footed, eventually leading to the Windows maker's ultimate demise in the smartphone space.

The company's legacy Windows Mobile platform was eventually replaced by a more modern Windows Phone operating system, but it came years after the first iPhone launched.

The move proved to be too little, too late. Microsoft officially ended support for Windows Phone in July of this year — just after Apple unveiled iOS 11, and as hype for the upcoming iPhone X was in full swing.

Neil Hughes

Neil Hughes

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

39 Comments

First the Windows phone and now Kinect.

I thought they said the Kinect was the future of computing. A game changer, in fact. Oh, well, people who are always making predictions about the future are often wrong, although they'll never admit to it.

"Windows Hello" deserves some sort of acknowledgement here, if only to point out that even when Microsoft beats Apple to market on the same implementation, they somehow fumble the ball. (see Time Machine, countless other examples…)