Looking back at John Sculley's rise as Apple's CEO, and fall on October 15, 1993

Last updated

After Steve Jobs, the best known head of Apple was John Sculley and yet he resigned from Apple in profitable disgrace just as the company was headed toward destruction. AppleInsider looks at Sculley's tenure with the company, and how history has treated the man since.

Next time you're asked to become CEO of a major company, make sure you negotiate your exit fee before you sign the contract. For until you sign, until you start the job, the company wants you and could give you practically anything. That's surely what John Sculley did because when he resigned Apple on October 15, 1993, he left with the equivalent in today's money of $17.5 million.

That included severance pay, a one-year consulting fee and also Apple's commitment to buy Sculley's mansion and Lear jet.

This is the man who is most famous for firing Steve Jobs — or so it appeared — and in 2009 was described by CNBC as the 14th Worst American CEO of All Time.

He didn't even top the list. (Dick Fuld of Lehman Brothers took first place.)

And the reason Sculley resigned on October 15, 1993 was because of what had happened the day before when Apple announced its quarterly results.

The firm did actually make a profit and it even increased its sales — but just barely enough to beat the dire predictions of analysts. The reality was still dire, though, as Apple's 1993 fourth-quarter earnings were down 97 percent from the same time in 1992.

To put this into context, this means that Apple's net income was $2.7 million in this 1993 quarter compared to $97.6 million the year before, which is equivalent in 2023 to $5.74 million and $207.4 million. We don't know what Sculley was earning in 1993, but CNBC says that in 1987 he was the highest-paid executive in Silicon Valley, taking home $2.2 million annually.

That's the equivalent of $5.95 million in 2023 and it was hard to support in a company doing so badly. It was also hard to stomach — for even if it weren't routinely believed that Sculley fired Jobs, you can imagine he wasn't the most popular person at Apple then.

Yet it all seemed so very different just ten years before.

Sculley joins Apple

You know the famous line that Steve Jobs said to John Sculley when persuading him to join Apple. "Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world?"

He said it because at that moment, Sculley was president of Pepsi. Up to then he was famous, if only within the retail industry, for how he created The Pepsi Challenge.

Again, that's not quite accurate, but Sculley commissioned research that ultimately led to this long-running ad campaign. The ads featured members of the public in a blind taste test between Pepsi and its then much more successful rival, Coca-Cola.

Unsurprisingly, in every ad shown, Pepsi won. However, it's fair to say that Pepsi genuinely won at least most of these taste tests that were tried.

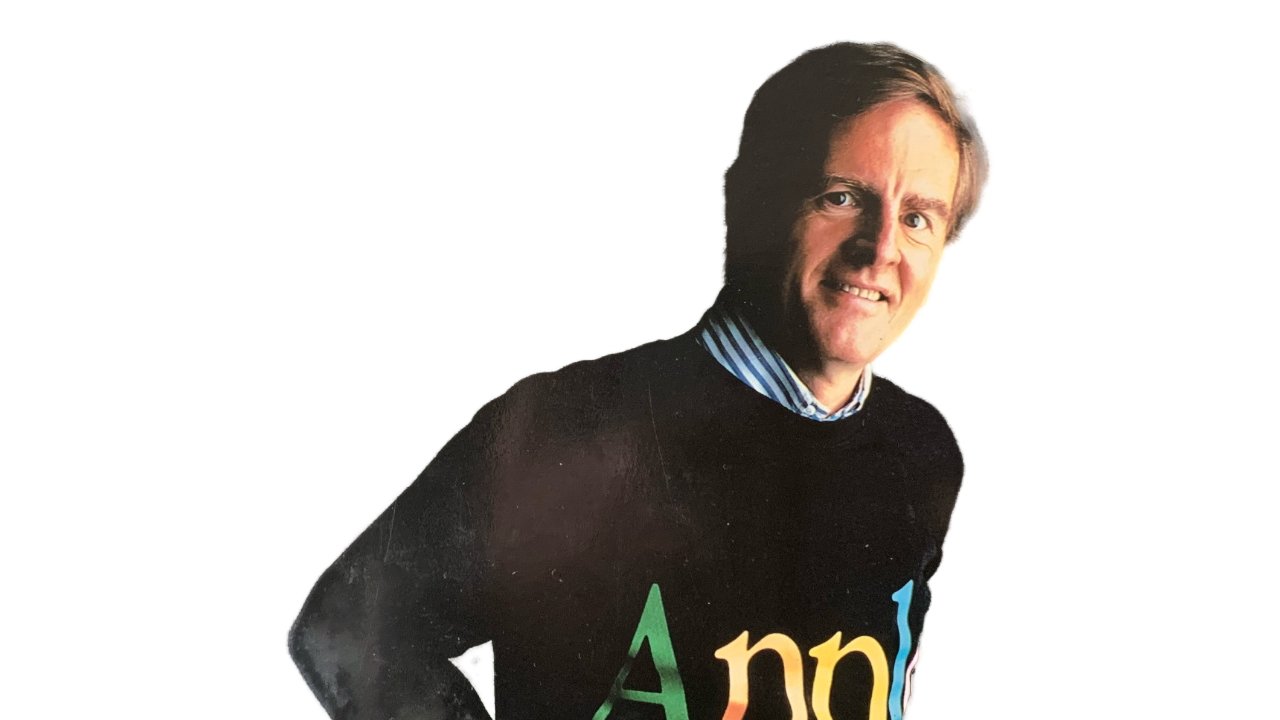

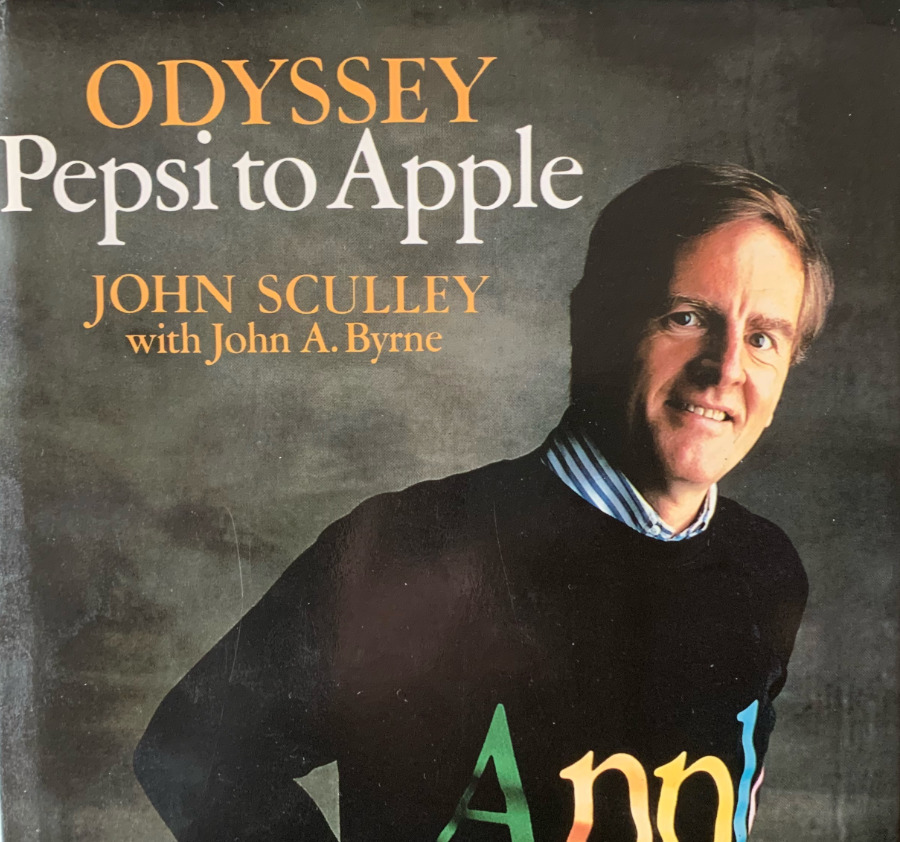

In his 1987 book, Odyssey: Pepsi to Apple, Sculley says that his study "showed that, on a blind basis, consumers overwhelmingly favored the taste of Pepsi over Coke. But Pepsi only won the taste test when both Pepsi and Coke remained unidentified. We didn't know how to exploit this competitive advantage, so we didn't act upon it."

In a move reminiscent of what Apple refers to as a skunkworks, one Pepsi executive ignored the company, went ahead and worked up what would become the Pepsi Challenge anyway. When the Pepsi board, including Sculley, then refused to pursue the idea, Larry Smith, Executive Vice President for Pepsi's bottling plants division, just did it himself.

He hired an ad agency and created the campaign. That was in 1971 as Sculley was moving to Pepsi's international division, but whern he returned in 1974. Sculley saw the challenge "as a far more powerful idea" than he had.

Where Larry Smith had done the Pepsi Challenge to help in specific regions where the drink was being overwhelmed by Coke, Sculley turned it into a national campaign. He didn't have the idea and he didn't create the campaign, but Sculley took it across the US and that made it the famous success it became.

Although when Sculley himself took the Pepsi Challenge, he didn't go well. "I made the mistake of publicly taking the Pepsi Challenge once at the Daytona 500 car race in Florida," he wrote in Odyssey. "We had timed a massive campaign in the state to coincide with our sponsorship of the race. I took the Challenge and chose Coke! Fortunately, the media weren't there to witness my embarrassing gaff."

Steve Jobs and Apple

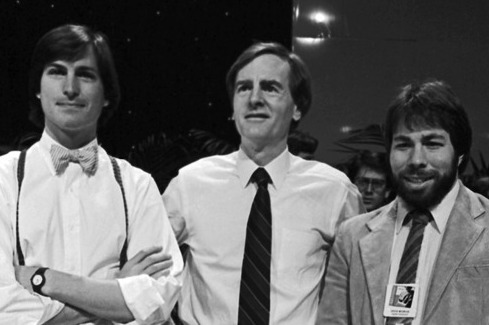

He's not as known as Jobs or Steve Wozniak, but Mike Markkula is crucial to Apple's story and to Sculley joining. Markkula guided Apple when it was a fledgling business. He even came out of retirement in 1977 to do so and had only intended to help the company grow for a few years before he would step away again.

However, circumstances meant he instead became president in 1981 and Steve Jobs took over Markkula's previous role as chairman. Apple's board, including Markkula, wanted a new CEO and Jobs made his choice. He wanted IBM's Don Estridge — but Estridge didn't want Apple.

It's said that one of Jobs's criteria for picking a CEO was that he or she must be someone Jobs could manipulate. If that's true, it ultimately didn't faze Sculley. After some 18 months of Jobs pressing him, John Sculley joined Apple.

He did it to change the world and it's not his fault that Apple doubled his his $500,000 Pepsi salary to $1 million. Or that Apple included $1 million in a signing bonus, a $1 million contract clause, the option to buy 350,000 Apple shares, and relocation expenses.

The Apple Challenge

It's easy to criticize Sculley for how Apple went downhill, but he did have successes. In particular, Steve Wozniak credits Sculley with the survival of the Mac.

"The Macintosh failed, really hard," he said to The Verge in 2013, "and who built the Macintosh into a success later on? It wasn't Steve, he was gone. It was other people like John Sculley who worked and worked to build a Macintosh market when the Apple II went away."

"You know, I loved the Newton. That thing changed my life," added Wozniak. "John Sculley got demeaned by Steve a lot, but he did the Knowledge Navigator, the Newton, HyperCard — unbelievable things."

Sculley also brought the Pepsi Challenge idea to Apple and created an equivalent campaign called Test Drive a Macintosh. In a 1984 edition of Newsweek, Apple took out 16 pages of advertising, costing more than $2.5 million according to [Owen Linzmayer's book, "Apple Confidential 2.0," promoting this idea.

You can read all 16 pages online and there were also TV spots to do with it.

If you had a credit card for security and you filled out a form, you could take home a Mac to try. Some 200,000 people did. However, Sculley was sure that just using a Mac would convince people to buy it.

You see his point but unfortunatley, it just didn't work out. Instead, a large proportion of Macs were simply returned at the end of the trial — and many were slightly damaged on the way.

1985 won't be like 1984

Steve Jobs and John Sculley were fast friends in every sense but they weren't for long. By 1985, there were strains. Apple was struggling financially and Sculley was persuaded that Steve Jobs was less an asset and more a liability.

It isn't true that Sculley actually fired Jobs, but they did have boardroom battles. Ultimately, Sculley removed Jobs from any kind of company responsibility.

This led to Jobs quitting to form NeXT. And it led to Sculley pressing on at Apple without him for another eight years.

What happened next

You could look at the post-Jobs era of Apple as being when John Sculley invented the Newton and so started us all off on a road to the iPhone and other smart devices.

The less generous view is that Sculley believed himself to be a technological innovator and he wasn't. (He has since said his lack of knowledge about computers means it was a "big mistake" for Apple to have hired him.)

He did create an idea called Knowledge Navigator which arguably predicted much of what we do today with the internet, yet it was more a collage of existing ideas set to music.

Apple did most definitely create the Newton on Sculley's watch, except he had to be talked into it. And bizarrely, at the very same time that he had a team creating the Newton, he set up another team aiming to make effectively the same thing.

That other team was later spun off into a separate firm called General Magic, which ultimately failed.

Then Sculley caved in to pressures from the Apple board and announced the Newton far, far too soon. He made a big splash with it, everything looked great, but it would take another 14 months before Newton was even just about possible to ship.

So then when it did, it wasn't as good as perhaps it could have been. It was definitely more expensive than anyone wanted — and with 14 months notice, competitors had a long time to create cheaper rivals.

You don't need to be an engineer to run a technology company and you don't need to be a visionary to make a success of a business. John Sculley acted like a visionary leader but he needed to actually set the trends in a timely fashion — or set the company's course to where those trends were going on time and not too early or too late — instead of bending to other pressures.

He was the archetypal corporate manager yet he failed to manage Apple the way that Apple needed to be run at the time.

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

24 Comments

**" but it didn't work out like that. Instead, a large proportion of Macs were returned —and many were slightly damaged on the way. "** LOL!!!

Quick tip: If you want to blast your computer with a shotgun, don't take it out on the poor, innocent monitor.*

*unless it's an iMac. In which case, sell it on eBay.

I think it's important to remember that neither Jobs not Sculley ever invented anything. They provided overview, guidance and parameters -- and enabled the Geeks to do their best geeking.

That's fairly obvious with Sculley but near heresy to say about Steve. But even Gates mocked him for being non-technical.

But, that doesn't mean that both were not geniuses in their own right. Geeks need geniuses like that to lead and guide and enable and to see the bigger, longer picture.

Terrible times for Apple back then. Please don’t even bother doing one of these for Gil Amelio.