The year 2014— when Apple debuted its A8 chip— might seem like the distant past. Yet it marked a turning point in Apple's struggles with Samsung and created a much larger new playing field for iOS carved from former Android users. Here's why that matters.

In 2014, Apple's larger new iPhone 6 models froze Galaxy sales at their peak. At the same time, the supply of A8 chips powering new iPhones was sourced from TSMC, Apple's new chip fab that won over production of the world's most advanced mobile silicon from Samsung's control. It's taken almost five years for the importance of these shifts to become widely understood.

A great awakening after a long age of ignorance

Across just the last year, Apple's valuation as a company has more than doubled. That kind of increase would represent phenomenal growth for a smaller tech company, but for a massive global firm already worth hundreds of billions of dollars, the dramatic scope of Apple's correction in valuation reveals a vast, entrenched, irrational history of ignorance on the part of investors, analysts, and journalists who have been deeply confused for years about Apple's prospects despite the company being one of the most transparent and straightforward success stories of the modern era.

From Apple's 1997 acquisition of NeXT into the 2000s, Apple's charismatic CEO Steve Jobs rolled out a series of curvy, translucent plastic computers followed by a lineup of increasingly mobile computing devices crafted from steel and glass, both captivating existing buyers and attracting new audiences in a world of bland commodity where PC rivals were largely trying to compete on price.

If Apple hadn't aggressively advanced its A8 silicon, there would not have been chips powerful enough to deliver iPhone X years later

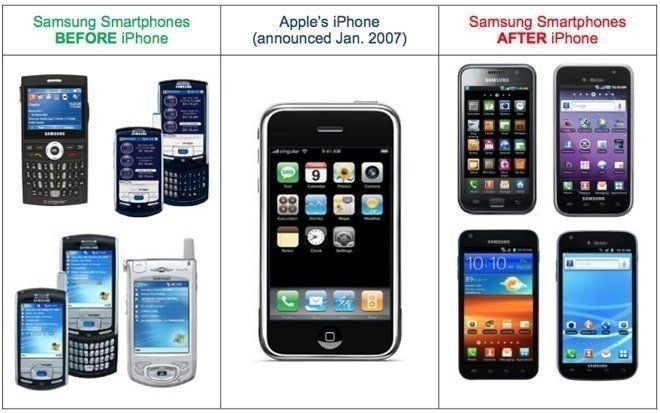

If Apple hadn't aggressively advanced its A8 silicon, there would not have been chips powerful enough to deliver iPhone X years laterRather than accurately detailing what Apple was doing— how it was outperforming its peers— most industry observers struggled to invent boogeyman narratives that desperately tried to identify the straw that would "finally" break Apple and shift its success to Google, to Microsoft, to Samsung, or to emerging Chinese firms. These competitors were all copying the surface appearance of Apple's products without investing similar efforts to deliver the underlying technology or operational capability needed to deliver success.

This smokescreen of nonsense purporting to be "fair and balanced" journalism was as about as valuable as a sportscaster attempting to "evenhandedly" narrate a game by avoiding any mention of the score, and instead desperately trying to portray the performance of the losing team as being "at least as good" as the winning team.

Particularly since 2010, a key enabling technology supporting Apple's dramatic rise over its competitors has been the company's internal development of the custom silicon chips used to power its iOS devices, starting with the A4, 2011's A5 and A5X, then surprising the market with an A6 and A6X that delivered a custom core design that diverged from what the rest of the industry had been pursuing. The following year, Apple's development of the 64-bit A7 in 2013 sent its silicon competitors into a full tailspin.

In 2014 Apple delivered another surprise with A8, increasingly dismantling the idea that it was hopelessly falling behind in mobile devices to the global community aligned behind Google's Android, and to Samsung in particular. It took time for mainstream audiences to realize the importance of the impact that Apple's A8 chip family would cause, in part because journalism was being re-optimized to stoke controversy and social interactions rather than inform audiences.

A false narrative in smartphones

By 2014, Apple had delivered four major generations of its Ax silicon— the A4, A5, A6, and A7 powering its iPhone 4, 4s, 5, and 5s— while Samsung was selling its fourth generation high-end flagship Galaxy S4. The two companies were also entering their fourth year of litigation triggered by Samsung's original release of the Galaxy S and Galaxy Tab, which Apple accused of patent and trademark infringement and unfair competition.

While stuck in an expanding legal battle with no end in sight— the lawsuits would ultimately stretch across most of the decade— Apple was reliant upon Samsung's System LSI chip fab to build its A-series silicon. So while Apple didn't have to share its increasingly advanced silicon with Samsung, it was still enriching its main rival in smartphones by keeping Samsung's chip fab busy and profitable. As one of the most technologically advanced factories on earth, Samsung's System LSI chip fab needed to consistently operate near its capacity to stay in business and maintain the massive investments that kept it state-of-the-art.

At the same time, Apple couldn't just yank its chip designs from Samsung's System LSI and take them to another chip fab, in part because a chip design and a particular fab process are incredibly interwoven, and in part because there are very few fabs on earth even capable of performing the state-of-the-art silicon work Apple needed at the scale demanded by iPhone and iPad shipments. Just like Samsung, every other advanced chip fab also needed to be booked to capacity to justify the costs of operating it.

Apart from Apple's unique delivery of 64-bit computing on A7— which a variety of bloggers had denied to even be significant— it wasn't broadly understood that Apple had much of a lead in silicon. Instead, it was popular to suggest that the surface of Android was "looking more modern" and that Apple's iOS was plagued with terrible issues such as the fantastically absurd story that Apple Maps was actually killing people by luring them out into the desert without water.

Google was actually funding this downward slide in intellectual discourse by actively shifting journalism away from intelligent curation by human editors into an automated clickbait and user-tracking business model that primarily rewarded upsetting sensationalism capable of pulling in views and instigating fits of "social interaction" without any regard for the actual value or accuracy of reported "news."

Playing into this game, bloggers invented the idea that Apple was in the difficult position of suffering from poor sales of iPhone 5c because of channel checks suggesting the company had made production cuts to the new phone because of disappointing sales. The reality was that the iPhone 5c was successfully outselling Android flagships as well as rival Blackberry and Windows Phone offerings.

False stories about the sales performance of iPhone 5c— essentially a repackaged version of the previous year's iPhone 5— were particularly bizarre because it was also clear Apple was shifting production from its cheaper iPhone 5c to its more expensive, all-new iPhone 5s due to customer preference for the more advanced and expensive model— something nobody had anticipated and which seemed both irrational and implausible.

Financial analysts had largely nodded in agreement for years that Apple desperately needed to compete on price with cheaper Androids in the range of $300 to gain critical market share. When the $650 iPhone 5c first debuted, many complained it was not cheap enough. Instead of being right, what actually occurred was that the majority of Apple's customers willingly paid a premium for the even more expensive iPhone 5s, being drawn to its new Touch ID security features, its fast new chip, and a significantly improved camera.

Apple was not only selling more units of its best and most expensive iPhone 5s, but was also deploying its new 64-bit A7 more rapidly than it had even anticipated, effectively paying off the expensive design work it had invested to beat the rest of the semiconductor industry into 64-bit mobile computing— and achieving that goal even faster than planned.

Yet rather than losing credibility, the more that bloggers stretched credulity to advance the bizarre narrative that Apple was in dire straits and "failing to innovate," the more they were rewarded by ad networks optimized to attract and blow up emotional social interactions rather than inform audiences.

After living through another five years of Apple obliterating its competition in market after market, driven by advances in silicon, computational photography, Augmented Reality, and state-of-the-art facial recognition, prolific tech journalist Kara Swisher got on CNBC to repeat the tired trope that Apple was "failing to innovate" just prior to the company's valuation doubling.

After another five years of leading the world in innovation, pundits are still claiming Apple is "failing to innovate"

After another five years of leading the world in innovation, pundits are still claiming Apple is "failing to innovate"A false narrative in tablets

Outside of phones, there was even greater ignorance building up in a steaming pile that obscured the reality of Apple's vast lead in tablet computing. Rather than even trying to understand how Apple was maintaining its leading position in global tablet sales while only offering premium-tier iPads, clickbait media pundits such as Jim Edwards of Business Insider screamed to their audiences that Apple's entire iPad business was "collapsing."

Android fans had initially been congratulating Google for the extreme cheapness of its simplistic Android tablets built by Taiwanese partners. But Google's $199 Nexus 7 mini-tablet was actually so terrible that by the middle of 2013, even Android's most devoted fans began to describe it as an "embarrassment to Google."

Rather than aiming for cheapness, Apple's 2014 iPad strategy followed the same path to success as the premium-priced iPhone 5s by introducing iPad Air 2 with a radically enhanced, 64-bit A8X chip with support for Touch ID. While the active use of most cheap Android tablets from 2014 ended within a year or two, iPad Air 2 continues to be supported by Apple's iPadOS 13 today, five years later. Both individuals and enterprise customers saw the contrast in value between Apple's premium iPads— with years of ongoing software updates— and the unreliable tablet experiments of Google and Microsoft.

It's also noteworthy that both Microsoft's Surface RT and Google's Nexus 7 had relied on Nvidia's Tegra 2. Both failures helped kill the future prospects of Tegra silicon. That was the opposite of what was occurring at Apple, where successful, profitable sales of iPads were enabling Apple to aggressively invest in the future development of new Ax silicon.

This was not a secret, but tech media journalists were contorting themselves to avoid saying it because it undermined their nonsense narratives that every product being offered for sale was equally positioned in the market and that price was the only factor to consider in making a long term purchase.

Samsung's new Note phablet supports a slipping phone lineup

While pundits promoted the idea that iPhones were too expensive and that a cheap new model was desperately needed, they were also celebrating the appearance of an expensive new line of premium "phablet" devices from Samsung including the Galaxy Note: a mini-tablet that was larger than a typical phone and paired with a stylus and a $100 premium over Apple's best iPhone.

By 2014, Galaxy Note had become Samsung's brightest star despite modest sales. It was more expensive, more profitable, and attracting more attention than Samsung's basic smartphones— which were actually failing to successfully innovate.

As it made excuses for falling behind Apple in 64-bit silicon, Samsung's standard Galaxy S5 also delivered a dysfunctional, insecure "swipe" fingerprint reader, helping to establish that Samsung didn't take security very seriously. Samsung also hadn't bothered to follow Apple's security protocols such as requiring a passcode after 48 hours, meaning a stolen device could be leisurely hacked over an extended time, even after powering off.

Further, without developing its equivalent of Apple's Secure Enclave, early Android phones with fingerprint sensors (including the HTC One Max and Samsung's Galaxy S5) stored fingerprint data irresponsibly in a way that allowed attackers to extract users' fingerprint data from device storage, as reported at the time by security firm ElcomSoft.

Samsung Galaxy S5 claimed a fingerprint sensor "just like iPhone," except that it was slow and insecure

Samsung Galaxy S5 claimed a fingerprint sensor "just like iPhone," except that it was slow and insecureAnd while Apple's A7 introduced Imagination's new PowerVR Rogue GPU architecture, Samsung took a step backward, removing premium PowerVR graphics and reverting to basic ARM Mali graphics in its own Exynos 5 Octa 5422 used in the Galaxy S5. It was also becoming clear that Samsung's cheapening out on the GPU while ramping up the display resolution of its mobile products was resulting in a poor gaming device, despite games being the most popular mobile app category.

In the spring of 2014, Samsung bragged that it shipped more Galaxy S5s into the channel than it had Galaxy S4 models the year before. But by the end of 2014, it was clear that Samsung's Galaxy S5 was not selling as well— down 40% over the previous year, according to the Wall Street Journal, despite earlier "channel checks" having suggested that Samsung had confidently built 20 million more units.

Samsung's low risk, conservative strategy of copying the surface of what seemed to make Apple's products successful had seemingly been paying off. However, any dip in sales volumes of its higher-end models at such minimal margins would end up devastating to profitability. The Galaxy S5 was also earning additional criticism for its lazy design and adware bloat. That all helped to strip the allure from Galaxy S, which Samsung was hoping to establish as a luxury brand equal or even superior to Apple's iPhone.

Apple's A8 claims new territory from Androidland

It wasn't until 2014, after several years of exploratory work, that Apple could finally begin mass-producing its first chip at Samsung's main chip rival TSMC: the A8. That new processor was used to deliver Apple's first "phablet" sized phones in the iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus. Apple's expansion into multiple new iPhone offerings was enabled in part by lessons learned the previous year in selling iPhone 5c.

Apple moved A8 production to TSMC, Samsung's rival chip fab based in Taiwan

Apple moved A8 production to TSMC, Samsung's rival chip fab based in TaiwanApple also introduced its new Metal API for accelerated gaming and other graphical operations. The magnitude of this advance wasn't appreciated at the time either, but owning control over its graphics has enabled faster, more efficient performance and facilitated advances in Augmented Reality and elsewhere.

Strong sales by Apple's new 2014 models eviscerated the profits of Samsung's Mobile IM group, particularly damaging the sales of its star phablets. The fact that Apple's A8 processors were now being built by Samsung's arch-rival chip fab was even worse, as it meant that for the first time, Samsung wasn't supplying the most valuable component in iPhones just as Apple experienced its biggest surge in new iPhone sales ever.

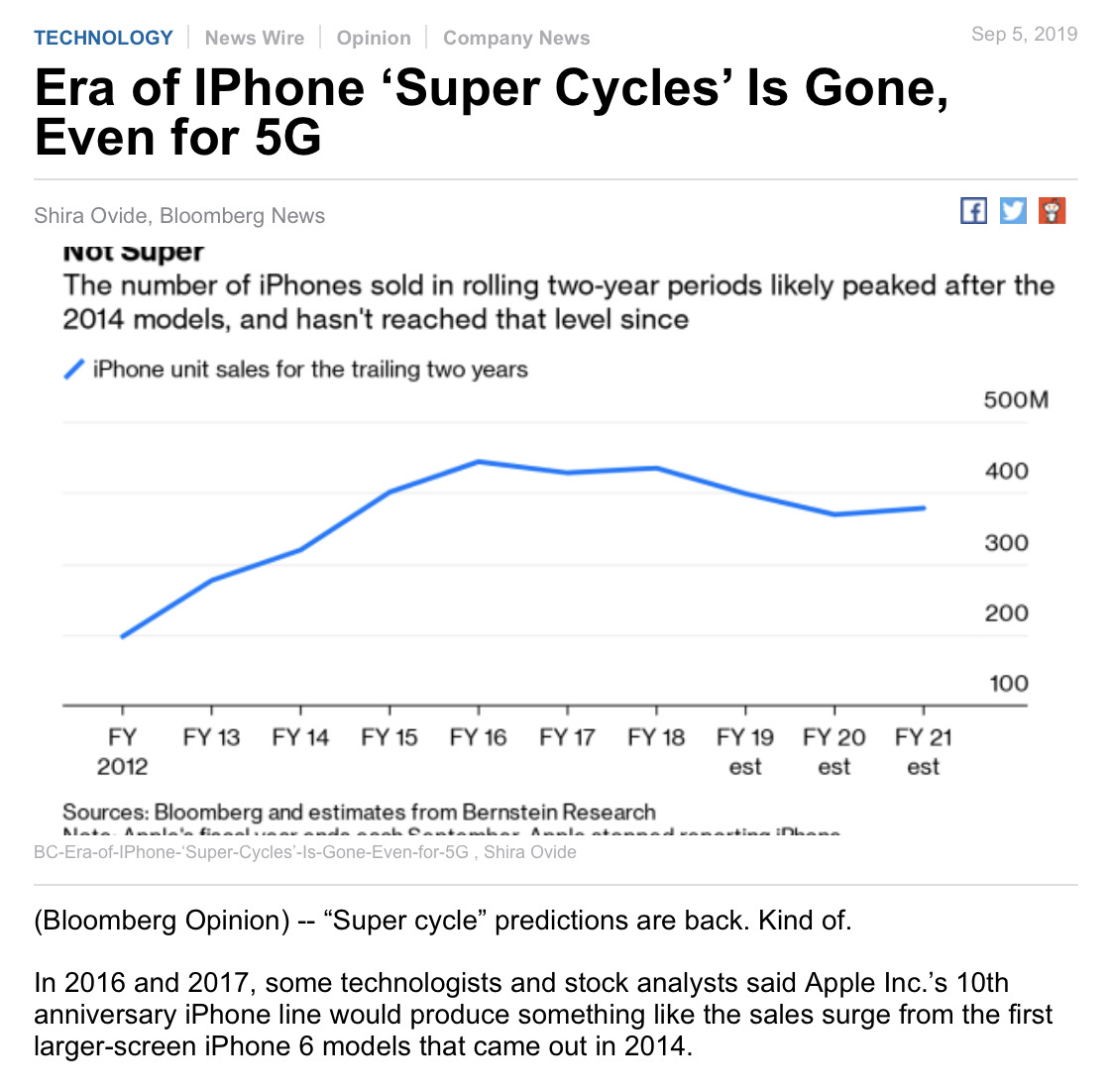

Apple's historical sales reports make it clear that an entire segment of Galaxy users switched to iPhones and never came back. Samsung's premium Galaxy sales didn't exceed their former peak, and Apple's new base of customers didn't ever flow back to Android, resulting in a new annual tier of iPhone sales volumes above 200 million units, up from the fewer than 170 million iPhones sold in the previous fiscal year.

Pundits would later call this a "supercycle" in hindsight and have regularly predicted— incorrectly— that a new "super cycle" would occur again at virtually every subsequent iPhone launch. But what happened was not a temporary surge in unit sales, but a long term expansion of Apple's installed base. Apple's iPhone gained new territory that Android would not subsequently win back.

Individual Android makers have seen their phone shipments "surge" in and out of the unit shipments lead, without much consequence or permanence. In many cases, this has occurred as Android makers have moved downmarket to introduce waves of new low-priced smartphones in China, India, Africa, and other emerging markets. Yet as already seen in the U.S., Japan, and China, the existence and popularity of basic smartphones have offered fertile ground for Apple's expansion of premium iPhone sales.

Android makers are effectively reclaiming new ground from the remaining oceans of users who previously lacked a smartphone, creating new territory for Apple to expand into in the future. Reclaiming that new ground isn't very profitable, but subsequently upgrading those users to iPhones is. Research groups who specialize in estimating only units shipped offer no understanding of what is actually occurring in the markets they are studying.

Apple's 2014 introduction of larger iPhones, appropriated from Samsung's experiments with Galaxy Note and its ever-larger Galaxy S flagship phones, didn't just cut deeply into Samsung's premium sales. It also contributed to an 11% rise in iPhone ASP as buyers migrated toward larger, more expensive new models. Apple's unit sales grew by 37%, but its iPhone revenues grew by 52% percent.

Back in 2014, members of the tech media adamantly insisted that Samsung would have no problem recovering from its slump, and often suggested that it wasn't even really in trouble at all, while also expressing grave concerns that Apple would have trouble exceeding its results the next year. Additionally, Apple's decreasing revenues from its "other hardware" category— mostly legacy iPods— and its decline in peak unit sales of iPads after 2014— in tandem with the introduction of larger iPhones— were both held up by bloggers as evidence that Apple wasn't operating perfectly in every metric.

Apple went on to use the A8 chip to power its 2015 Apple TV HD and iPad mini 4, and later reused it again in the 2018 HomePod. Apple also used its A8X variant clocked faster and with new customizations to the GPU to enhance the performance of its high-end iPad Air 2, which paved the way for future expansion into more expensive, powerful iOS-based computing with iPad Pro.

Starting in 2015, Apple leveraged its rapidly increasing silicon design sophistication to deliver new growth in two markets the industry and its bloggers had decided were dead, as the next segment will detail.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Bon Adamson

Bon Adamson

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

-m.jpg)

31 Comments

I seriously wish bloggers and mainstream media would tell us facts instead of click bait. “Apple is doomed” is what sells eyeballs. YouTube is just a a bad 90% of the time. “I left Apple for Android” sells. It’s Google so I don’t expect better. But mainstream journalists should report fact. And Apple fact is usually missing.

Apple has one of the best silicon design teams in the industry, and it’s complemented by writing great firmware which makes for a high performance iPhone with great battery life. Before A8 Intel was the leader in silicon process technology for their CPU’s, but now TSMC is the leader with 5nm technology while Intel is still struggling to get out 10nm CPU’s in volume due to defects. So not only has Apple advanced in their technology road map it has been an enabler for TSMC to do the same. Apple’s A chips has basically given TSMC the customer it needs to fill its expensive state of the art fabs, without Apple TSMC would not be producing 5nm IC’s, and I’m sure both companies realize this. Apple’s next generation iPhones will enable rear camera time of flight capability enabling precise 3D effects unseen in the industry.

Great article! My only quibble is that this is in the past tense: "

But, that's a different discussion. Thanks for writing this. It's a really good read.