Back in April, Apple announced that it was partnering with Google build a technology framework to help governments and health agencies reduce the spread of the virus, with user privacy and security central to the design. I got COVID-19, and here's how it worked.

Apple's Find My technology recycled for COVID-19

Apple's speed in deploying an entirely new layer of technology for securely tracking COVID-19 exposure notifications — just weeks after the pandemic burst onto the world stage — is easier to understand when you realize it wasn't entirely new technology.

Like the aluminum in its iPads and iMacs, the privacy-centric Bluetooth key sharing mechanism Apple developed to track COVID-19 exposures had a former life. Last summer at WWDC19, Apple's software chief Craig Federighi outlined a suspiciously similar approach to tracking "exposures," albeit rather than tracing pandemic spread, the technology had been applied to finding lost hardware.

Apple's then-new "Find My" system was designed to locate products like a stolen MacBook, even if not connected to WiFi or mobile data networks. The system leveraged Bluetooth radios to regularly trade encrypted keys that could then be used to report to a user the last time some other Apple device (including a stranger's) had crossed paths with their missing gear.

The company stressed that neither any stranger's device nor any other third party— not even Apple itself— would be able to intercept these encrypted keys to decipher the lost product's location. Only the user who had reported something missing would get the information that might help them find it.

"Find My" becomes Apple's privacy prescription for COVID-19

Virtually every other major player in the consumer technology sector focuses on finding new ways to collect even more data on their users, which can be used to track and profile them to boost the value of micro-targeted, crowd behavior manipulation campaigns. Instead, Apple developed a new privacy-centric system that, by design, refused to collect and store any data that could be used to influence, exploit, or surveil end-users.

Apple subsequently delivered its new key-based Find My feature last fall in macOS Catalina and iOS 13. Find My was promoted as a sophisticated and novel way of performing a useful task for users without exposing any personal data, without materially affecting anyone's battery life, and without creating any publicly accessible records of a user's location that either a malicious hacker, a snooping corporation, or a spying government could intercept or subpoena and use in any way.

Its entire design jumped through complex technical hoops in order to respect users' privacy. That's something that Apple has made a key part of its product marketing to differentiate its premium-priced, privacy-preserving products from cheaper commodity Androids and Windows PCs that make user surveillance, adware, and behavioral tracking a core element of their monetization.

For emerging new product categories ranging from "smart TVs" to voice-first microphones, fitness trackers, and home camera drones, surveillance advertising now commonly subsidizes loss-leader hardware in many cases.

"Find My" COVID-19 Exposures

As COVID-19 began to ransack Apple's supply chain and pose a significant threat to its users, the company realized that it could repurpose the technology it had already perfected for its "Find My" service in 2019 to deliver what it initially called a "Privacy-Preserving Contact Tracing" system earlier this year.

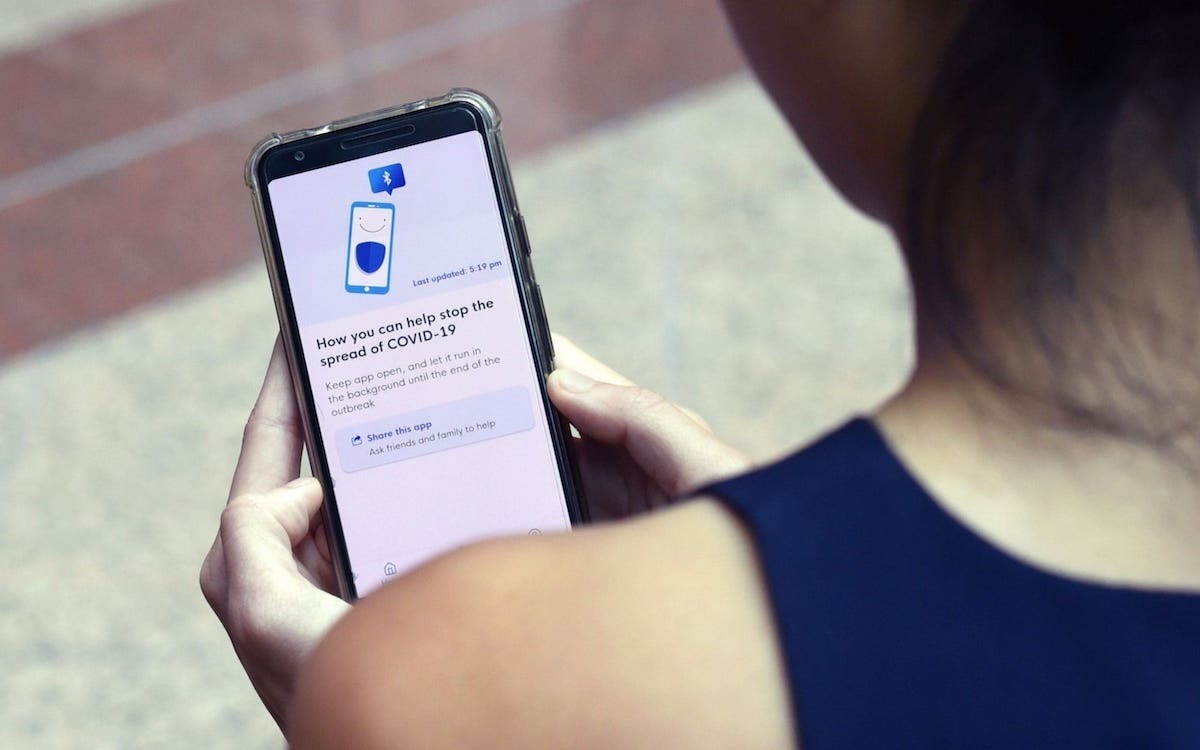

A major problem remained — who would build a public health system that only served iOS users? Rather than promoting the technology as a system that would only benefit affluent users of iPhones, Apple entered an arrangement with Google to make the technology available to Android users.

That meant not only that Android users could benefit from the "contact tracing" system, but that they would also be anonymously contributing valuable, private data that could help everyone else too. This enables various automated systems to more rapidly reach a critical mass of installed users in each country that adopted the system.

Apple carefully coached its public relations statements to make it sound like it was sitting down with Google to invent something new that would be immediately deployed as an API that public health developers could use within a matter of weeks. To anyone who has ever been remotely involved with the development of any non-trivial technology, this idea was absurd.

Equally absurd was the idea that Google had any interest in protecting its users' privacy. Yet, Apple's genius in crediting Google as a partner helped it to rapidly deploy its technology far faster than it could have on its own. Presenting the effort as a "privacy preserving" initiative — and suggesting that some of the technology came from Google — was successful in deflecting criticism from iOS antagonists and presented a unified front against governments that were desperately seeking to expand their own control over users' data.

At the same time, Apple also announced from the start that once the thread of COVID-19 was over, the contact tracing API would be removed from both iOS and Android. It wasn't merely a gift of technology that Apple was unreservedly sharing with Google.

Resistance from governments looking to surveil citizens

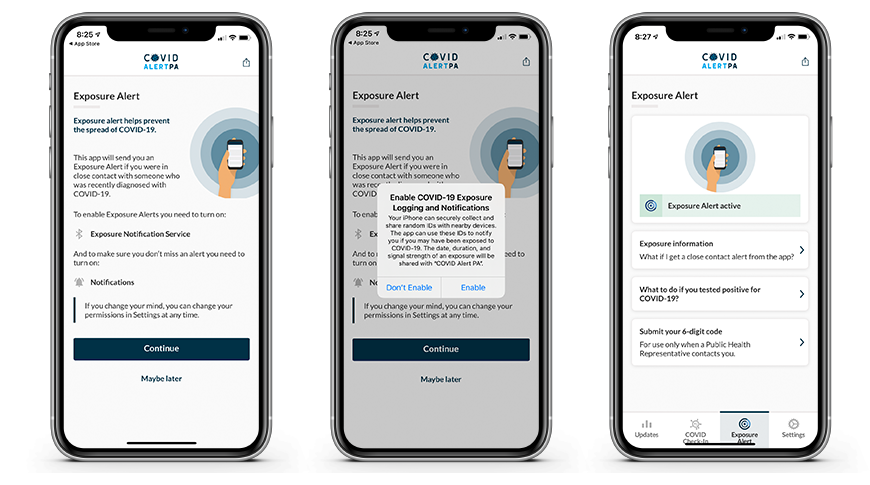

Apple quickly renamed its "Privacy-Preserving Contact Tracing" platform to "Exposure Notification," in acknowledgment of the fact that its "Find My" system was not actually a "contact tracing" system because it didn't offer government agencies the actual names and contact information of anyone involved with reported exposure to COVID-19. Instead, it only delivered a simple warning to end-users involved with potential exposure to the virus.

This was initially a showstopper issue for a variety of politicians and public health agencies who were accustomed to contact tracing without any notion of privacy. For example, in the United States and various other countries, citizens have limited "rights to privacy" if they are diagnosed with a disease that is known to be highly contagious and a threat to public health.

For example, all 50 states in the U.S.A. require that any syphilis cases be reported to the state or local public health agency to enable them to find and treat any other potentially exposed persons. When COVID-19 began to explode, causing immediate and severe health problems for infected individuals with a highly contagious spread among close contacts, public health agencies were not nearly as interested in "user privacy" as they were in stopping rampant increases in death.

For that reason, a variety of governments initially sought to build their own "centralized" tracing systems rather than using the "privacy-preserving" technology that Apple had developed. Even France, Germany, and the United Kingdom were initially notable holdouts in adopting Apple's exposure notification system. Only after their internal systems failed were they interested in adopting the technically superior approach Apple had largely perfected and already broadly deployed in its "Find My" system in the previous year.

App developer Deutsche Telekom: why are people still bitching?

Germany, the UK, and most recently Norway have all relented and abandoned their own efforts to adopt Apple's "exposure notification" API. However, while that approach has had some success, there are still a variety of problems that remain.

Germany's Corona-Warn app was recently profiled in a blog posing by Nicole Schmidt, a spokesperson for Deutsche Telekom, the leading mobile carrier that worked with SAP to create the app. The posting marked 100 days of app development since the two firms began working to implement Apple's exposure notification API.

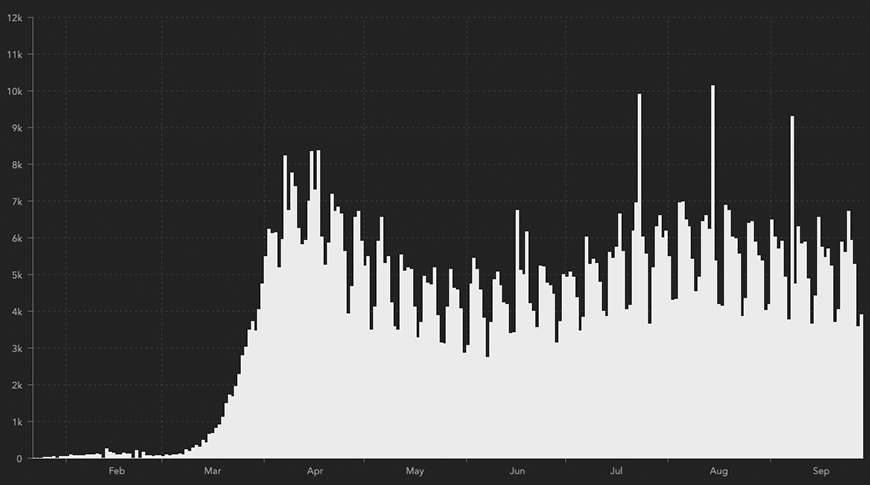

"This is not a cheering article," Schmidt wrote. "This is a critical review after 100 days of the Corona-Warn-App." The posting noted that "SAP and Deutsche Telekom programmed the Corona-Warn-App in only 50 days. In the first 24 hours after the app's launch alone, there were six million downloads, a total of over 18.4 million downloads in 100 days."

In typically blunt German frankness, Schmidt added, "So everything is good then? But then why are people still bitching? Let's take it one step at a time."

Schmidt then outlined that Germany's app "has more downloads than its counterparts in all European countries combined," referencing 18.4 million downloads while acknowledging that "downloads are not users. That is true. We currently assume 15 million active users. This figure is also a strong number and is quite impressive."

Schmidt detailed that "the App is a double premiere. First, we have integrated the new Exposure Notification Framework from Google and Apple, a special interface for Corona Warning Apps. Secondly, we have shown that Bluetooth functions as a means of determining distances, thus enabling important basic research based on which further improvements are possible. This is digital pioneering work by SAP and Telekom."

Schmidt didn't elaborate on how SAP and Telekom freshly stumbled upon the well-known idea that Bluetooth can be used to "determine distance," but does detail that outside of the "digital pioneering work," there were also problems.

"Errors: Errors? Yes, there have been. We had problems with the interaction with the operating systems of Google and Apple, confusing screen displays and error messages. With partnership, fast updates and hotfixes, we got most of it under control again after 24 hours," Schmidt said. "As a consequence, we test even more intensively."

"In our own test center in Dresden, the Corona-Warn-App is being tested around the clock on various smartphone models with Argus eyes. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that the complex interaction of the app, the exposure notification framework and the respective operating system may cause jerkiness in the future," added Schmidt. "Because, see above, digital pioneering work is required! But the SAP Telecom team continues to work on making the app more robust. This is how agile software development works. There is no finished product, and then you just sit back and do the work. A little better every day, so to speak."

Schmidt may have had in mind the turmoil that erupted in late July when SAP and Telekom blamed problems on Apple's iOS for errors in the app that prevented warnings from being delivered. Both companies, along with the federal government of Germany, distributed public messages blaming Apple. A report by Stephan Scheuer for the German business newspaper Handesblatt noted that politicians in Berlin where quick to "demand consequences."

Scheuer added that just a couple days later, SAP and Telekom changed their tune, admitting that Apple had previously addressed the problems ten days earlier in an iOS update, and that the two firms simply failed to notice while racing to blame Apple for the issues in public.

The kerfuffle was exaggerated due to the intense effort by SAP and Telekom to accept praise for their "digital pioneering work" and overall competency in delivering the app, while at the same time assigning public blame to Apple when anything when wrong, and deflecting any other criticism as "bitching."

"That's what the corporations are paid for," Scheuer noted, detailing that, "the costs for the Corona-Warn app will initially amount to around 70 million euros (about US $82 million). According to the Ministry of Finance, SAP is to receive around 9.5 million euros plus sales tax for the development of the app. In addition, there are two million euros for maintenance this year. The Telekom subsidiary T-Systems is to receive up to 7.79 million euros (plus sales tax) for the commissioning. In addition, T-Systems will initially be remunerated with 43 million euros for operation."

Germany's taxpayers paid nothing for the core exposure notifications API Apple developed and released for public use by governments globally, whether on iOS or Android. This makes it particularly remarkable that the corporations being paid to build and operate the app suggest that the technology is perhaps from Google but that Apple is to blame if anything goes wrong.

The app is working, apparently?

Without suggesting any credit to Apple as the designer of the exposure notification system, Telekom's Schmidt added that "the app was designed to reliably protect the identity of the users and their personal data, as broad sections of the population wanted it. This is the case, and the German Federal Association for Consumer Protection has just stated once again that the Corona-Warn-App is a 'showcase project in data protection'."

"As a consequence, there is no way to look inside the system and count on how many smartphones the app's algorithm has triggered a risk warning," Schmidt added. "But we are seeing more and more reports on social media and in local newspapers that app users have been warned. So no one needs to worry - the warning via app works."

Apple's privacy-preserving design does indeed make it difficult to monitor the results of apps built using the API. There's also another issue that complicates evaluating the effectiveness of these apps: the fact that there are now so many, with most being developed independently in parallel to different standards and local policies.

Due to the reality of political borders, each country— including each state in the USA— has to develop and operate their own version of the exposure notification app. Countries may also choose to distribute their national app only in the corresponding regional App Store, or in other regions where it might make sense to download it.

That means Americans using Apple's U.S. App Store can't download Germany's official Corona-Warn app unless they set up a German App Store account under a separate Apple ID and jump through the arduous and poorly-documented hoops in iOS to use apps from multiple App Stores.

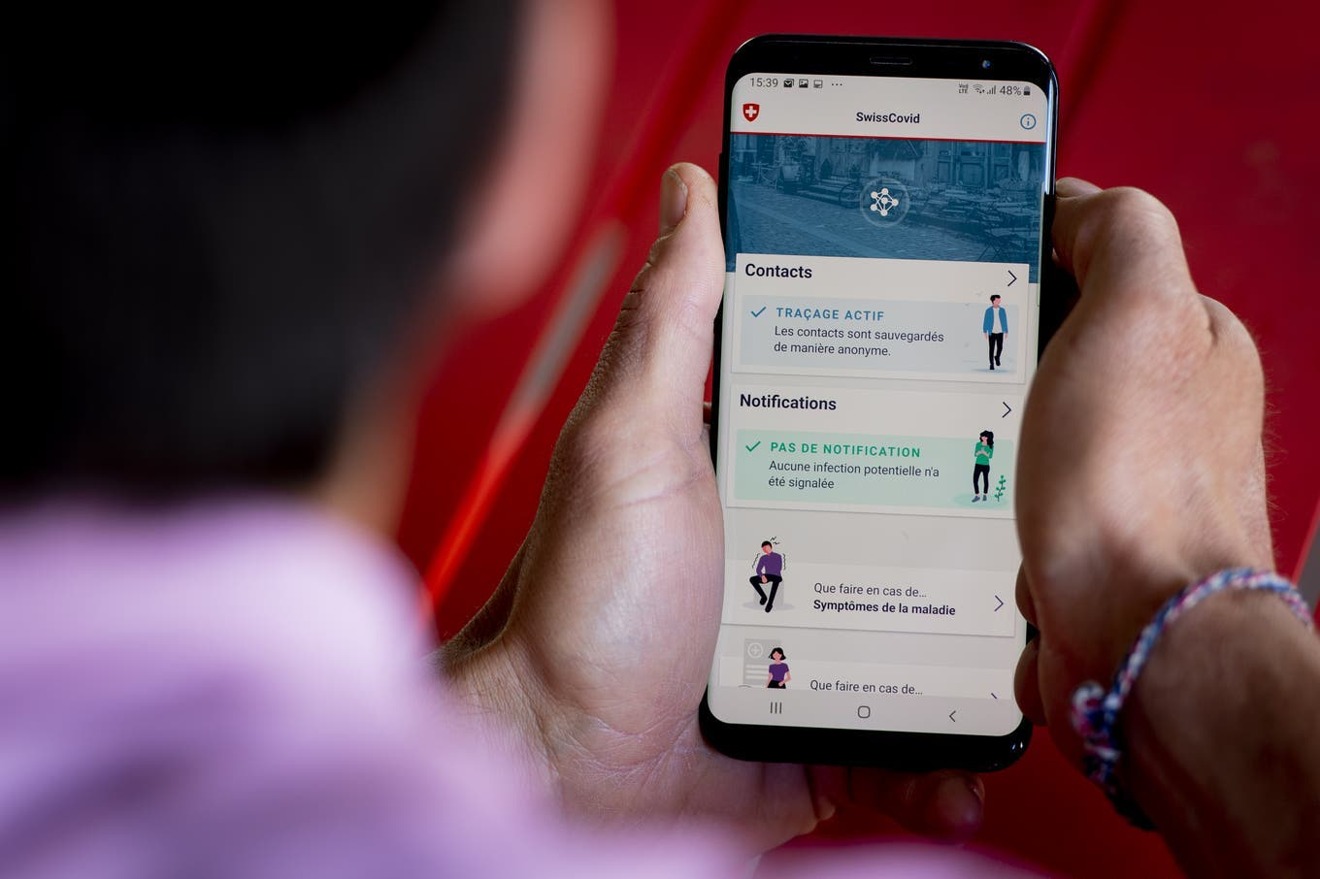

Additionally, a user in Germany crossing the border into Switzerland would also need to download the official "SwissCovid" app if they want to be able to track and report exposures while in another country. While both countries distribute their apps in the App Store of neighboring nations, they don't seem capable of actually coordinating their exposure notifications.

I got COVID-19 to test this out

I didn't intentionally get infected with COVID-19 just to figure out whether Apple's exposure notification system was working, but it ended up that my experience might offer some additional insight to the situation.

A few weeks ago, I developed some flu-like symptoms involving body aches and exhaustion. It only lasted a couple days, and I didn't ever develop a fever. It felt a lot like the flu-like symptoms I suffered through earlier late last winter, right as COVID-19 began making headlines. Back then, I initially thought that perhaps I'd been infected, but without available testing, I had no evidence. Over the summer, I got an antibody test just to get some clarity, but it came back negative.

So when I fell sick again, it was less concerned that it might be COVID-19, especially after quickly feeling like it had passed. After several days of generally feeling like I'd made a full recovery, I set off on a trip to Switzerland. Several days before leaving, I downloaded Germany's official Corona-Warn app and configured it to monitor iOS's exposure logging for the days I was in Germany leading up to my Swiss road trip.

When I arrived in Switzerland, I downloaded the official SwissCovid app (also using Apple's German App Store) and switched logging from Germany's app to the Swiss version. Apple's iOS only enables one app to access exposure logging at a time, as configured in Settings. When I switched to Switzerland, Germany's app showed no exposures had been recorded over the past few days.

In Switzerland, I joined a friend for a road trip through the majestic mountains down to the border of Italy and back up to Zurich across five days of exploring the limits of an EV Tesla on an extended tour of autobahns across the green expanses of Helvetia. About halfway through, I felt like I was struggling to stay awake while hiking up mountain paths but otherwise enjoying a rather relaxed trip.

At one point, I struggled to sleep with racing thoughts of "what if I am dying" as my lungs burned and every muscle in my body ached. I wasn't sure if it was going nuts and psychosomatically falling apart, or if I had suddenly grown old over the last few months of idly staying at home most of the time. The truth is, I'm not that young anymore, and potentially could be one of those people who rapidly decline in health over a matter of days due to the ravaging damage that COVID-19 causes.

I felt new kinds of pain in ways I'd never felt before. Simply rolling my eyes hurt, as if my ocular muscles were ready to give up. I felt like every bit of motor control in me was inflamed and worn out as if 25 percent of my body just gave out, and the rest of me was dragging it around. I spent hours looking at the ceiling contemplating whether I should make end-of-life arrangements or whether I was fine and just needed some rest that my brain wouldn't let me have.

That anguish eventually subsided, in tandem with some of the most sleeping I've done as an adult. While I really wanted to go out and explore more on my trip, my body forced me into bed as early as 8 PM, and I regularly crashed out deep into the next morning. A bit of mountain hiking, and I was again ready for an afternoon nap. I wondered if perhaps it was just the higher mountain elevation of the Alps.

After my friend dropped me back off in Zurich, I spent the next three days trying to explore around and see things. It felt like an extraordinary task to get out of bed, leave my hotel, and get anything at all done before crawling back under the covers. Despite feeling wiped out, I didn't feel sick, wasn't coughing, and didn't have a fever.

Upon flying back to Germany, I decided I should take advantage of free COVID-19 testing in the airport. I still had no fever or any symptoms I'd associated with COVID-19. In fact, Germany's free airport testing is only offered for symptom-free travelers. People with a fever or struggling to breathe are supposed to report to a medical provider, not stand in line waiting for a routine but gaggingly-deep nose swab performed by university volunteers and implemented by what looked like German military reservists. After I was tested, I was given a printed out barcode and told to go home and wait for results.

The bar code could be entered into Germany's official CovidWarn app, which I again configured to be the logging app in iOS. Once linked, the app showed the test as pending without results ready yet. Two days later, I got an email stating that my test had come back positive and that I needed to quarantine for ten days.

I dutifully notified everyone I'd spent any time around over the past few days. I also incrementally began to feel better. The German CovidWarn app began telling me that I had "3 exposures with low risk," but never updated to show I'd had a positive result. Instead, the linked test continued to show up with "results not yet available."

That's not Apple's fault, of course. The exposure notification system was working on some level, although the apparent delay was concerning. Even more troubling was that neither the German nor the Swiss app was being used to communicate my recent positive result to any of my potential exposures. Neither app was even acknowledging my positive test result!

It appeared that Germany had failed to ever update its own positive test result linked to me. But there was also the problem of Switzerland: how would that nation's system know I had tested positive in Germany? I called the Swiss contact in the app and was told I needed a test ID number that only a Swiss test would have provided.

I was then referred to the regional Canton government health authority, the Swiss equivalent to a state. Similar to the U.S., each Swiss Canton largely manages its own laws and regulations independently of the national government. But I had traveled through a swath of Cantons on my trip: Zurich, St. Gallen, Graubunden, Ticino, Valais, Uri, and Schwyz.

Switzerland has 26 Cantons in an area that's only half the size of South Carolina or Maine. Political boundaries seemed to be erasing any the potential benefit of an exposure notification platform of any kind, particularly for travelers who would be the most likely to benefit from, or contribute warnings to, such a system.

Over a week later, neither Germany nor Switzerland has used my positive test result to send warnings through the system Apple created. That's important because the timing of exposure notifications have a very limited useful window. By the time I got a positive result, I likely wasn't even contagious any more. The friend I traveled next to for a full week subsequently tested negative and never developed any symptoms.

Tracing experts are not sold on Apple's "privacy protecting" approach

It could be that Germany never bothered to update my test result because its tracing experts don't see any benefit to it. The agent who called me after my positive email shared his own frustrated opinion with the app because it doesn't provide actual contact information. It was his job to find those contacts and try to notify them.

I'd already done about as much of that as I could after I got the positive result delivered via email. I hadn't had many significant contacts with others outside of the car. I had dutifully worn a face mask in public without knowing whether I was contagious, simply out of an abundance of caution. I wasn't going to bars or restaurants to eat inside. Yet many people I observed in Switzerland, particularly older people, were not wearing a mask.

Perhaps they were running the SwissCovid app, but without Switzerland communicating with Germany, that wouldn't do anything in my case. Even Germans running the COVID-Warn app weren't getting any notifications related to my test result, although, by that time, the notification key data from the previous week was probably discarded as being too old, and any new data didn't matter because by that time, I was in quarantine at home.

There were other interesting things I was told by the contact tracer who called me shortly after my results. First, I was asked about my flight data and seat on the airplane. But once I told him that my entire adjacent row was empty, he decided it wasn't worth it to investigate further, because only passengers seated directly next to you are counted as a potential exposure. If Germany were using its exposure notification app to the maximum extent possible, my phone would likely have sprayed Bluetooth keys around to users seated directly in front and behind me, offering a second layer of notification beyond the apparently narrow concept that manual tracers follow. But it isn't.

Additionally the tracer told me that it wouldn't be useful to get retested again after a few days, as I would almost certainly continue to test positive for weeks or even months. Yet those results wouldn't necessarily mean I was still contagious, because people can test positive long after their viral load has dropped to the point where they aren't still shedding enough viruses to infect others.

On top of that, he noted that it was also possible that when I got blood tested for antibodies earlier in the summer, while I may not have developed any antibodies, I could have already developed a parallel immune response to an earlier exposure. That can occur in the form of T-cells, which are not antibodies but play a similar role in identifying foreign proteins in cancer cells or virus infections and either destroying them or signaling the body to react.

While the COVID-19 coronavirus is new, it does share some structures with other existing coronaviruses which some people have already developed an immune response to. That helps to explain why different people have wildly different responses to infection. There are a host of other reasons, too, including the intensity and duration of each viral exposure and other preexisting health factors.

Exposure notification doesn't work if the tests don't work

That indicates that neither testing negative nor positive is a simple matter of being infectious or even sick or not. While testing can certainly help to manually trace exposures during outbreaks and help authorities to take actions to prevent further spread, they can't guarantee anything about the health or risk of a specific individual being tested.

And if a user's test result isn't even added to a given exposure notification app, it certainly isn't going to trigger any automated notifications in the way Apple designed its system to work.

It is much easier to securely track lost devices using Apple's privacy-paramount technology in "Find My" than it is to trace COVID-19 exposures, particularly because "Find My" isn't encumbered by political boundaries or by agents who might not see the value of actually using it in the course of their tracing jobs because it doesn't simply provide them with a list of names to contact as they expect.

While it appears that the CovidWarn app didn't work as intended in my particular circumstances, it still is true that Germany was among the first to implement an app using Apple's exposure notification API. In the USA, various states are still trying to launch something. For example, in Washington state, the University of Washington is still working with Microsoft volunteers on what it says is for "demonstration purposes only."

Even by the start of September, only half of the states in the U.S. had reportedly even "explored" Apple's notification exposure API while only six have delivered something. That prompted Apple and Google to introduce "Exposure Notifications Express" for iOS and Android, a program that folds more of the app into the OS itself so that states have less work to do. This spoon-feeding effort is currently limited to the U.S., where COVID-19 app development has embarrassingly trailed other advanced nations.

And of course, even if states deliver exposure notification apps and correctly use them to deliver testing results, the apps only function if people download and use them. Apple's "Find My" is almost certainly locating more lost MacBooks for iCloud users simply because the system is available, was rolled out rapidly and didn't depend on outside consultants or governments to decide to lend their support.

This all happened before

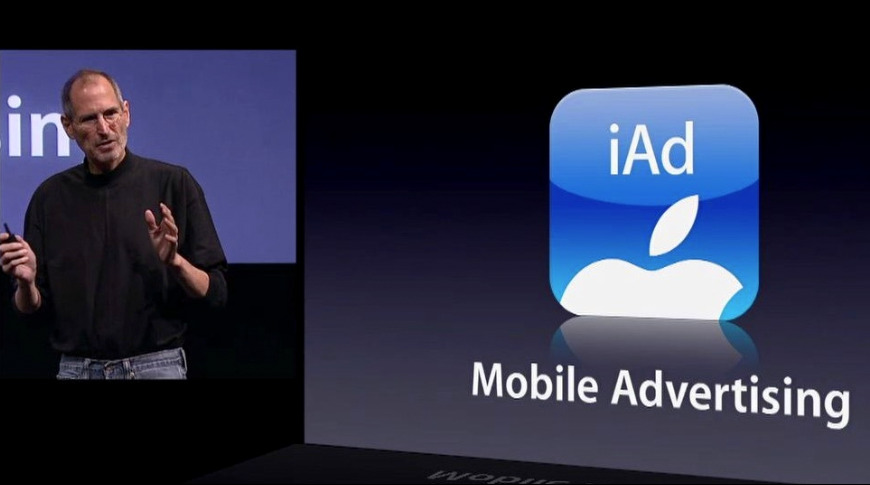

This saga might remind you of a previous technology introduction Apple made to address another issue that was once plaguing its users: annoying web ads in mobile apps. Ten years ago, Steve Jobs introduced the new iAd as a major feature of iOS 4. At the time, Apple expected its users to prefer a privacy-protecting system that could help to monetize free and low cost App Store titles while also benefitting app developers by enabling a classier opt-in, in-app ad experience that didn't just drop mobile users on a web page when they clicked on a banner.

Users were initially receptive to the idea. However, Apple failed to anticipate how poorly iAd would be received by the advertising industry, which saw the program as a threat to their ability to spy on users and surreptitiously collect more data than Apple would ever allow. Their response came in the form of absolutely scathing attacks on iAd, and their press releases were gobbled up and regurgitated by content bloggers who loved the story that Apple had somehow failed.

In a parallel universe where Apple had instead been successful and unchallenged with iAd, it could have ended up as a major player in online advertising in a way that shifted the company's commercial interests out of alignment with that of its users, the same way that Google has shifted from "organizing the worlds information" to simply becoming the parent of DoubleClick ads since 2007.

Additionally, instead of a decade of developing an intense privacy focus under Tim Cook that increasingly identified surveillance advertising as threat to its users, an iAd-driven Apple conceptually might have joined most of the rest of the industry into plowing the majority of its research into how to improve ad revenues by supercharge tracking cookies and tracing users' behaviors with device fingerprinting, microphone spying, and other grotesque techniques.

In fact, in this imaginary world with a wildly profitable iAd business, Apple may have never developed key technologies to protect users' location, biometric, and health data from unscrupulously amoral advertisers like Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

Apple might never have pursued privacy-focused health-related products like Apple Watch, HealthKit, ResearchKit, or this complex system intended to find users' lost products without revealing anything personal about them.

Had Apple pursued advertising the way everyone else has rather than building high-end privacy-centric products that don't need surveillance advertising monetization, it would also likely not have developed the secure system for tracing random connections between Bluetooth radios last year that it realized could be reused to help trace COVID-19 infections this spring.

It remains difficult to say whether the agencies who are adopting Apple's "privacy protecting exposure notification" are going to really make correct use of it enough to have a major impact on controlling the pandemic's spread.

However, currently, Germany is seeing mixed but noteworthy results and experiencing fewer deaths across its population. At the same time, Americans are far more limited in what they can safely do while the U.S.A. leads the world in deaths from a pandemic its American corporations were quick to offer solutions for.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

12 Comments

The Covid tracing technology is developed by the Swiss research institute EPFL. Apple and Google adopted the idea. https://actu.epfl.ch/news/carmela-troncoso-named-one-of-2020s-global-top-you/

First, let me say that I’m very happy to hear that you appear to have recovered from your encounter with COVID, Dan. I hope there will be no long-lasting repercussions.

I’m a little concerned that you don’t provide any sources to your claim that Google did practically nothing in this “partnership.” I certainly agree that your theory makes sense, and I’m in no rush to defend Google (that’s Gator/GoogleGuy’s job, I expect he’ll be along shortly), but you would have benefitted by contacting Google to get some details on what they claim they contributed to the project (or even a “no comment”), or some confirmation from Apple that they did all the work and Google just made sure the API would work on Android, as you seem to say.

I appreciate your hands-on report of how the app works (or didn’t very well) in Germany and Switzerland. I hope your friend escaped being exposed. I’m pleased that Apple has pre-loaded the tech into iOS 14 so that when an app is available it “just works.” What America really needs is a national version of the app, but haha good luck with that. With the US’s borders closed between Canada and Mexico, a national US app would be highly effective. In places like Europe, a regional/European app would be far more effective than state-by-state.

This article contains no additives, and is certified 100% prime cut Gatorbait.

So you spread Covid all over Switzerland, great job

Dan, thank you for your vivid description of what was certainly a harrowing experience. It reminds me a little of that terrible time you had after coming off your motorbike a while ago.

It was certainly interesting to hear how the Exposure Notification works in real life situations. It never occurred to me that a health authority wouldn't bother or be unable to update a positive test result. I wonder if Apple will be able to work out some way of engineering past other roadblocks like this.