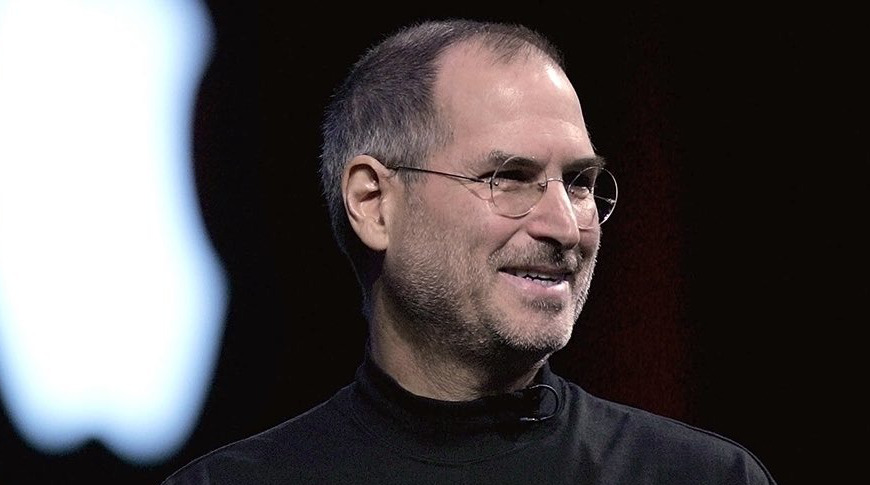

When he returned to Apple, Steve Jobs dismantled its typical corporate structure and radically changed how the entire business was managed. The benefits of that rethinking about corporate structure are still being leveraged today.

The largest corporations, and Apple is the biggest in the world, are fully aware of how susceptible they are to two key management problems. They just rarely do anything about them because the corporations are so big that fundamental change is impossible — unless you're Steve Jobs.

What besets giant corporations is a combination of departments becoming entrenched competitors, and the Peter Principle. This is the idea where people are promoted and promoted until they reach a management job that they're unable to do. They then stick at that level, continuing to fail to do the job, and eventually every management position is filled by people who can't do it.

According to Harvard Business Review, when Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, it appeared to be a big corporation. It had around 8,000 employees and its revenue for the year was $7 billion. Compared to 2019 — when it was 137,000 employees and $260 billion in revenue — it wasn't all that big. Yet it had at least the first signs of these problems.

The way it surmounted them back then is exactly how some of its most innovative work since then — such as adding Portrait Mode bokeh to the iPhone — could possibly have been achieved.

Breaking Apple's conventional corporate structure

As long as a company can produce the goods, few customers have any reason to care how the firm is managed, or how big their managers' offices are. Over the almost quarter century since Jobs rejoined Apple, though, his corporate business reshuffling has been precisely why the company has been able to produce the goods.

In 1997, Apple was one corporation effectively containing many companies. The Mac was under the control of one such business unit, complete with its own general managers. This division, like all of them, also had its own financial structure — it was responsible for its own Profit and Loss (P&L) accounting.

That typical accounting structure has ramifications that Steve Jobs didn't want. It means you, as a general manager, are responsible for what you spend and what you earn. And the result is often that you stop looking to the long term and instead just focus on keeping costs down and profits up in the short term.

Jobs scrapped the separate business units having their own P&L. From late 1997 onwards, Apple had one single P&L for the entire corporation. Now if you needed extra staff to get a new Mac design finished, you didn't end up trying to make cuts elsewhere in your devision.

Firing managers

At the same time, according to Harvard Business Review, Jobs created what's called a functional structure. It means leveraging expertise in what the company makes, rather than having people who are really solely professional managers.

"We went through that stage in Apple where we went out and thought, 'Oh, we're gonna be a big company, let's hire professional management,'" said Jobs in 1984. " We went out and hired a bunch of professional management. It didn't work at all"

"They knew how to manage, but they didn't know how to do anything," he continued. "If you're a great person, why do you want to work for somebody you can't learn anything from? And you know what's interesting? You know who the best managers are? They are the great individual contributors who never, ever want to be a manager but decide they have to be... because no one else is going to... do as good a job."

That's really typical Steve Jobs. He presents that idea of training up experts to manage as if it is flawless and also what he's always espoused.

It does ignore what other companies have seen, where an ability to be brilliant in producing work simply never translates into being brilliant at managing other people to do the same thing.

Plus he may have said that in 1984, but he didn't implement it until he returned to Apple in 1997. In the meantime, he may also have had the idea truly tested from how he set up NeXT.

Although NeXT never became the giant corporation he had hoped, it had spent a great deal of money preparing to be that big. NeXT was built to be a large corporation, with typical corporate-style processes and management.

Whether Jobs regretted having investing in that or whether he saw the disadvantages, when he came back to Apple he was fully against typical corporate-style management, and now put that belief into action.

Apple's management ethos

Jobs criticized managers who could manage and yet not actually do anything. Once he had replaced all of them with product specialists, engineers and the like, he started a process where all Apple managers had to possess certain characteristics.

Harvard Business Review says that every Apple manager, from 1997 to today, has been required to have a deep expertise in their area. They must be able — and willing — to become involved in the details of their field. And they have to be able to collaborate with colleagues over making decisions.

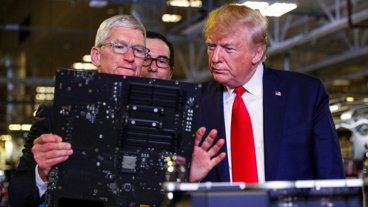

Tim Cook's evolving Apple

The Apple of 2020 is not the Apple of 1997, yet it retains this functional structure because it works. According to Harvard Business Review, Tim Cook has kept the one P&L, but adjusted how the company's work is divived.

So Apple's human interface teams used to be part of software, but now Cook has them merged with the previously hardware-specific industrial design. It's combining expertise to leverage how these areas now complement one another more than they did.

These areas are now larger than they were, too. Compare the 1990s issues of working on, say, printers for Macs, with 2020's Machine Learning and AI which affect the entire company.

It means that managers are less able to be complete experts in all the elements of their area, it means that they need to teach more people about what they know. And it means that they have to learn new areas.

Apple's management structure is still functional — look at how Tim Cook's likely replacement is current COO Jeff Williams rather than an outsider — but the functionality is growing.

Managers are inevitably becoming more like the standard corporate model as the sheer volume and scale of work they're in charge of means that they have to rely on experts to do the work they cannot.

But Apple's aim remains the same. It wants the people who make the decisions to be the people who actually know what they're doing. And it's this that has meant innovation has thrived at Apple where it's been systematically stifled in other corporations.

Keep up with AppleInsider by downloading the AppleInsider app for iOS, and follow us on YouTube, Twitter @appleinsider and Facebook for live, late-breaking coverage. You can also check out our official Instagram account for exclusive photos.

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

-xl.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

-m.jpg)

9 Comments

“We’re the worlds biggest startup!”

The HBR article is a very interesting read. This tactic of replacing managers who don’t know the object of their department and only focus on money and managing people with people who are known experts in their fields is a fascinating idea. I wonder how Jobs came up with it. I also wonder why more companies don’t do the same, especially specialized manufacturers. Of course now that the word is out, maybe more corporations will adopt this practice.

For a long time the mantra for companies was to emulate “The Toyota Way.” Toyota’s business model, management structure, and manufacturing methods were touted as the best in the world. To succeed you had to be like Toyota.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Toyota_Way

Companies are now starting to look to the “Apple Way” as a model for success. And with good reason.