Every quarter, the tech world's market research firms release metrics on how many PCs, phones and tablets Apple reported selling and compare these to estimates of what the rest of the world produced, resulting in headlines that minimize the importance of the world's largest and most profitable company. You might wonder why.

Macs and market share

Following a routine that began in the 1990s, Gartner and IDC spent the 2000s noting that Apple's Mac market share was virtually irrelevant, afloat in an ocean of PC sales without giving much regard to the fact that Apple enjoyed very high share in some market segments (such as education and graphic design) and essentially none in others (such as enterprise sales, kiosks and cash registers).

On a worldwide scale, Apple's sales of Macs did seem to be a drop in the proverbial bucket. Between 2001 and 2004, Apple's global annual Mac sales hovered around 3 to 3.5 million while the entire PC industry grew (according to Gartner) from 128 million to 189 million, an expansion of over 47.6 percent. Without Macs growing much at all, Apple's "share" slipped from 2.3 percent to less than 2 percent.

Things began to change in 2005, just months after John Dvorak penned his market share-centric prognostication of doom, "Grim Macintosh Market Share Forebodes Crisis," paragraphs of misguided negativity about Apple based almost entirely upon misleading market share statistics that appeared to drown the Mac in the expansive waters of P Sea.

Dvorak failed to see the potential for iPods and Apple's strategy for iTunes, complaining of these initiatives, "none of these has anything to do with the Macintosh," and (comically, in retrospect) observing, "much of the problem arises from the psychology created by the overpriced iPod. And Mac users who buy the players contribute to the problem by encouraging the company to maintain its high-margin death march."

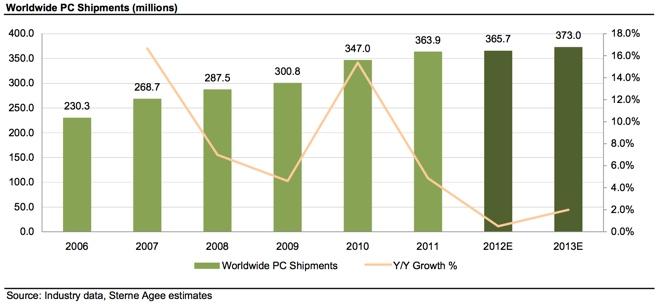

Over the next year, Apple's "iPod halo" and expanding retail stores helped Mac sales to rapidly grow, doubling sales to hit 7 million Macs sold in fiscal 2007. While Mac sales grew by 100 percent, the overall PC market (including Macs) only grew by 43 percent from 2004 to 2007. Over the next four years, Mac sales more than doubled again to 16.7 million in 2011, while the overall PC industry grew by just 16 percent. The next year, the PC industry actually contracted. Then things got even worse.

However, there was something far more disruptive happening to PCs than the expansion of Apple's Mac sales.

Rise of the mini Macs

While Mac sales took off, Apple was also building a new kind of personal computer: a highly mobile one. In 2007, iPhone packed a Mac into a handheld device. By 2010 Apple was selling 47.5 million iPhones per year, more than ten times the volumes of desktop Macs it had been selling in 2005. While Mac sales took off, Apple was also building a new kind of personal computer: a highly mobile one

Something else happened in 2010: iPad, a highly mobile personal computer with a tablet form factor. Shortly after it went on sale, Gartner and IDC stopped counting tablets as Personal Computers. Well not exactly; they stopped counting tablets that didn't run Windows as Personal Computers.

This prevented Apple from distorting their PC market share figures. As the PC market mysteriously flattened out (it failed to grow by more than 2 million units between 2010 and 2012, a pace more than twice as slow as that seen during the recession of 2008), Apple's iPad sales quickly ramped up to 58.3 million per year.

For 2012, Mac and iPad sales represented almost 19 percent of the global PC market, making Apple the largest PC vendor. However, rather than recognizing the very obvious impact iPad sales were having on conventional PCs, IDC and Gartner shifted iPad sales into a separate bin of "media tablets."

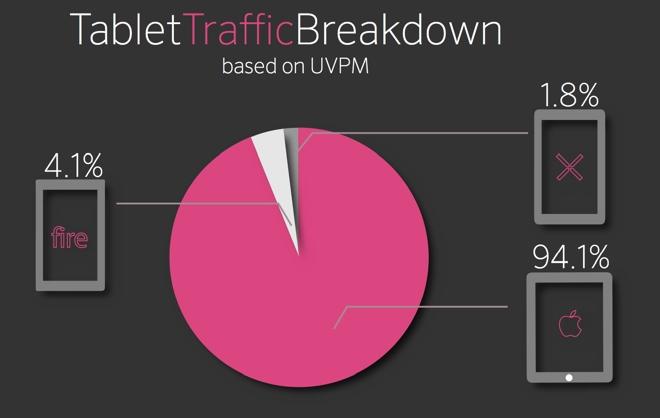

This took Apple's iPad out of statistical competition with PC, the product it was actually competing with in the market, and instead pitted it in a market share war with an avalanche of Android tablets, which were not having any clear impact on iPad sales at all.

Shipments of new Android tablets affected iPad about as much as the waves of MP3 players splashing at the feet of blockbuster iPods sales several years prior; nobody who wanted an iPod really considered MP3 alternatives, and everyone who bought a generic MP3 player did so only to not buy an iPod. iPads and generic tablets are seeing identical buying patterns today, with virtually identical ratios of buyers picking Apple.

Rather than battling generic tablets as market researchers and pundits had hoped, iPad continued to muscle its way into not just Apple's existing market niches (such as education and graphic design) but also those long held by generic PCs (such as enterprise sales, kiosks and cash registers). Generic tablets haven't gained much traction anywhere.

Playing CalvinBall in Personal Computers

In fiscal 2013, Apple's huge volumes of iPad sales increased 22 percent over the previous year, despite the incessant warnings of Garter, IDC and now Strategy Analytics that Apple's "share of the tablet market" was actually falling.

Why was it newsworthy that Apple's "tablet share" was falling within a "market" of devices that are having little readily discernible impact on iPad growth and essentially no impact at all on iPad's education, enterprise or usage share, while the iPad's readily apparent, devastating impact on conventional PC sales in education and enterprise markets as well as in general use by consumers was rarely even hinted at by Gartner, IDC and Strategy Analytics?

It could have been that market research companies were so used to dismissing Apple as an irrelevant also-ran that they simply could not fathom numbers that told a different story. Or it's possible that their numbers told a different story because they could not fathom not dismissing Apple as an also-ran. Tasked with deciding whether to award first place to winner they gained nothing from awarding, it simply made more sense to change the rules of the game in order to continue playing.

Stacking the deck against iPad

Over the past year, the failure of Android tablets from Amazon, Samsung, Asus, LG, Microsoft and Google/Motorola to live up their sales predictions (or have any substantial impact on the iPad at all) has demanded a new tactic in the anti-counting of Apple's iPad.

This summer, Strategy Analytics borrowed a page from the 1990s playbook of Gartner and IDC in inventing a "white box" market for unbranded tablet devices. This allowed the firm to count over ten million "tablets" that exist elsewhere, devices whose sole purpose almost appears to be statistical.

The firms counting these devices need not connect them to a particular manufacturer's sales nor profits, nor explain why the devices have left no discernible footprint anywhere on earth: no impact on web traffic, no retail store traffic, and no boosting of tablet apps or media sales.

This quarter, IDC similarly began counting tons of new "white box tablets," discovering so many that it had to update its year-ago figures just to include them all. This seemed so suspicious that IDC's Ryan Reith offered to clarify why this retrofiguring was done.

The search for Red Octablet

Reith explained in a phone conversation with AppleInsider that IDC had embarked upon a months-long study of ODM (manufacturer) research, which turned up a "significant surge in low end devices."

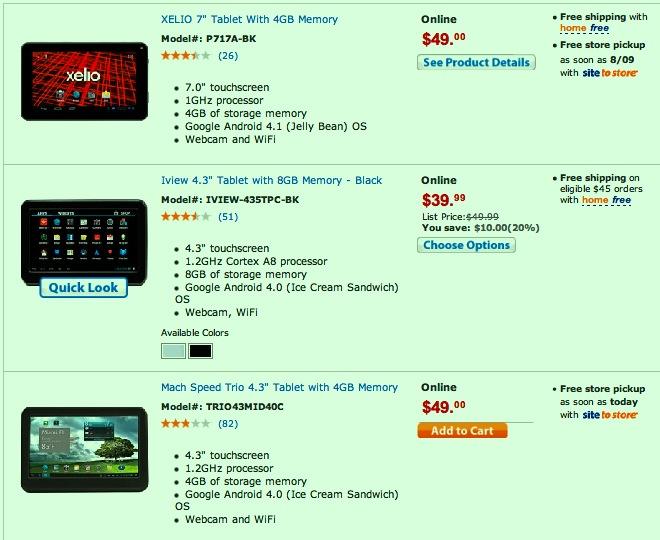

It turned out that by reducing the definition of "tablet" to include anything that involved a 7 to 16 inch screen, a "known CPU" and a "recognizable operating system" (which might include Linux, but just not any embedded, proprietary software apart from Windows, Android or iOS), one can come up with huge volumes of devices: two thirds of the global "tablet market."

These aren't "tier one" tablets like the Samsung Galaxy Tab, Google Nexus, or Microsoft Surface that are all stubbornly refusing to sell or have any real impact on iPad sales. Instead, these "tier two" products feature CPUs as slow as 600 Mhz, and might include what Reith offhandedly described as "kids tablets or toys."

Some of these are in fact offered for sale by Walmart (below) or Amazon, often at prices under $100. Others range higher toward $250, but if anyone were willing to pay $250 for a tablet, why wouldn't they choose Google's $230 Nexus 7, with reasonable sounding specifications and a brand name, offered without a profit margin?

Given that even Google's Nexus 7 refuses to sell in serious quantities (IDC says Asus, its manufacturer, only sold a total of 3.5 million tablets during the new Nexus 7's Q3 launch quarter), it appears that there is scant demand for "good" Android tablets, forcing the "tier two" crowd to aim low at $40-100 price points, effectively being ewaste trinkets that primarily serve to embarrass the customers suckered into buying them.

What is the relevance of digging up this "tier two" garbage, counting it as a serious product offering, and then announcing that, given the discovery of piles of junk being shoveled into inventory channels, that Apple's iPad "market share" has fallen? Particularly when the same market research firms are studiously avoiding any comparison between conventional PCs and the iPads that are stampeding through their historical markets, a move of noteworthy significance?

Reith acknowledged that the definitions of PC and tablet created by market research firms are arbitrary distinctions, but said he couldn't speak to the numbers calculated by other firms' researchers. The tablet market descriptions by Gartner and Strategy Analytics sound quite similar to what IDC outlined, allowing all three to describe huge pools of "white box tablets" even if their actual numbers are each off by millions of units each quarter.

Strategy Analytics leaves behind a motive clue

There's little mystery of who shot down the iPad's market share or what weapon they're using: all three major market research firms rapidly fire off headline bullets clearly aimed at wounding the perception of Apple's tablet. One can, generally, only speculate about why this is occurring.

However, Strategy Analytics has offered some unusual transparency regarding its motive for carving out a very specific market and then stuffing the pie chart with "tier two" volume to the point where the world's best selling tablet is crushed down into an embarrassing statistical sliver of shrinking "share."

On the company's Clients page, Strategy Analytics notes that its "customer base includes more than half of the world's largest mobile operators and most of the leading infrastructure and device vendors, 13 of the top 15 handset OEMs, five of the top 10 semiconductor companies, two-thirds of the top twenty global operators, eight of the top 10 global automobile manufacturers, the top 10 electronics-focused tier one suppliers and the top 10 automotive semiconductor vendors."

Strategy Analytics sells its research, like Gartner and IDC, in the form of reports that cost corporate buyers thousands of dollars. Only a tiny portion of that data is outlined in the firms' public press releases, because those firms are in business to make money, not just give away collected data. In addition to selling reports, marketing firms also offer a variety of other consulting services.

As Strategy Analytics notes, "we support our clients with a variety of high-stakes projects, including: new product development and product roadmaps; driving existing products down the cost curve; bundled pricing strategies; infrastructure investment and optimization; new market penetration and market expansion; influencing consumer behavior and buying preferences, and many more short- and long-term initiatives."

Enhance!

That last line is particularly interesting because Strategy Analytics came out and said what lots of people have been thinking. Rather than being an unbiased source of purely factual data, Strategy Analytics disclosed that one of its most valuable "high stakes projects" for its clients is the practice of "influencing consumer behavior and buying preferences."

How exactly does reporting facts on sales result in "influencing consumer behavior and buying preferences"? Hypothetically, if one could fool the world's journalists into parroting off statistics that portrayed the most successful vendor of tablets as being in desperate straits and "failing" in a manner of speaking, it would sure take the pressure off of those who are failing to actually sell tablets, wouldn't it?

If you're Pepsi and you're getting outsold by Coke, why not print headlines that statistically compare Coke to every cola on earth, or perhaps every drink containing caffeine? Poor Coke! After inventing such news its "market share" would now ostensibly be slipping into irrelevance, calling into question the fact that it sells the most product in its actual market, makes the most money, and people everywhere pay a premium for its name brand. What a miserable loser Coke suddenly is, just with some creative reporting of meaningless, contrived statistics.

What about in the smartphone market, where one company has a product that is so far ahead of the rest of the industry that it can command a substantial premium per device while still selling in higher volumes than comparable devices from any other individual vendor? And of course, the iPhone isn't just "a Coke" but represents the iOS App Store and development platform, iCloud services and iTunes. It's an ecosystem. It's the new iPod.

Coke vs caffeinated... well anything in a bottle

Samsung just predicted that its premium phone sales for 2013 are expected to reach 100 million units, while Apple has already booked sales of over 150 million iPhones in its fiscal year ending in September, without including an estimate of the upcoming 2013 holiday season expected to set new sales records.

Everyone else is far behind Samsung (and note that Samsung's premium phone numbers include its "phablets," which are the vast majority of the company's tablet sales; Apple separately sold over 71 million iPads in the last fiscal year).

"Influencing consumer behavior and buying preferences" would require creating a composite of competing companies, pooling their sales together under the communal identifying ingredient of "Android," and possibly erasing the boundary between premium phones and stuff that can barely function beyond making a basic phone call.

Add up all this stuff and you could create the impression that the rest of the world is winning with 81 percent of somethingorother, distracting away from the fact that Apple is destroying its competition in both phones and tablets in the only market segments that a vendor with the luxury of being choosy would choose to do business in.

I'm sure nobody will catch on.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

215 Comments

Great piece.

Gartner, IDC & other 'market research' firms are all the same. You're either a tech company playing their game and paying them their dues or you get ignored. If you're actually successful despite being ignored by them then be prepared to have them talk your company and products/services down.

Do I blame them? No, they gotta make their money somehow. But I just hope anyone who pays for their reports realises they're paying for material that may as well feature in a tabloid for all the half-baked facts and opinions it'll be full of.

I think you are fundamentally wrong to look at macs in a general home computer market. Just like you'd be wrong to compare Porsches with Fords. Mac have never really been mainstream, but for professional users. Its not one market, its segmented such as: home, pro, and business users.

How very true ..... I remember 2004 and thinking Apple Mac share has dropped to 2 percent, thinking, how could this be?

The home market may be changing. I have moved from a windows desktop PC to an iMac just for home use. I became so fed up with Microsoft os and so pleased with my iPad and iPhone that when it came time to replace my computer Apple was the only choice. I now have a trouble free computer that works properly, something that I didn't have under Microsoft's os. Apple is no longer just for selected markets but for home users too.