For years, Apple's detractors have predicted that the company's industry-leading profits from Macs, iPods, iPhones and iPads would erode away as cheaper products from high volume competitors— and more innovative disruptors— emerged to knock it from its profitable perch, forcing the company to constantly invent new product categories just to stay alive. But that hasn't happened. Instead, Apple keeps increasing its profitability while also expanding into new market segments.

Apple Infinite Loop Campus

Analysts have long remained fixated upon the "next big product category" from Apple, imagining that the company is a hit-driven movie studio that's one film-flop away from disaster. That mindset appears to be responsible for the 2014 media campaigns that relentlessly sought to brand iPhone 5c as a failure, despite it being among the most successful smartphones to ever launch. When you're apprehensively looking for failure, everything looks like a boogeyman.

At the same time, analysts and commentators have insisted that Apple needs to be more like its less successful competitors, mistakenly hailing new low-end products like the Mac mini and incorrectly demanding new low priced iPhones to generate higher volumes of sales. This delusional mindset reveals a complete failure to grasp Apple's fundamental core competency— the secret to really understanding the potential behind Apple's next big thing.

Ten years of failed predictions for Apple

A decade ago, market analysts were looking for a "solution" to the "problem" of Apple's low market share among Windows PCs. IDC analyst Roger Kay and Jupiter Research analyst Michael Gartenberg both expressed cautious optimism about the prospects for a new product category then being released by Apple: the $500 Mac mini.

Despite lots of hope surrounding the low cost Mac mini and its stated goal in replacing PC boxes in quantities that could boost Apple's market share, the new product actually had very little impact on Apple or the PC market. The significant growth in Mac sales and profits since 2005 has come from notebooks, not desktops.

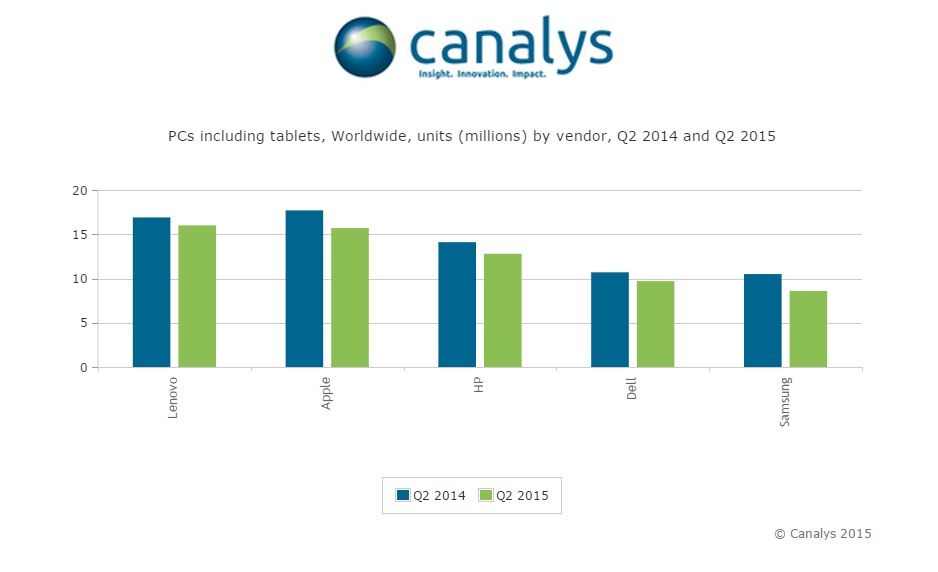

Five years later, Apple introduced iPad, which conversely received very little initial optimism from market analysts. However, iPad's impact on the PC market has been brutal. Since its introduction, Apple has gone from being a minority computer maker to being tied for the world's largest.

That iPad growth didn't come at the expense of Apple's Macs, which have similarly grown into a business smaller by volume, but one that's just as profitable as iPads. Over fiscal 2015, Apple sold 54.9 million iPads and 20.6 million Macs. iPads contributed $23.2 billion in revenue while Mac sales brought in $25.5 billion.

To put those numbers in perspective: both of Apple's computer lines each bring in revenues similar to HP's PC operations, but are each an order of magnitude more profitable because Apple's operating margins are over 30 percent, while HP's are closer to 3 percent.Both of Apple's computer lines each bring in revenues similar to HP's PC operations but are each an order of magnitude more profitable

Over the past decade, Apple not only grew to being larger than the largest American PC makers, but also became roughly twice as large by revenue and many times more profitable. And that's not even taking into consideration the far larger business of iPhones— a segment that's now so large that pundits like to talk about iPads and Macs as being relatively irrelevant to Apple, even though they represent two boots victoriously planted directly in the face of the defeated PC industry.

Why was so much hope placed in the Mac mini— a product that ultimately contributed very little to Apple's success— and so little potential seen in iPad— a product that literally ground to a halt all growth in the Windows PC industry? In part, both mistaken perceptions were based on a misguided view of Apple's value and core competency as a company.

Analysts who viewed Apple as just another PC maker saw hope in the Mac mini— a product that looked like a conventional PC— but failed to see much potential in a tablet device, given that Tablet PCs had regularly flopped for other PC makers. Now that the iPad has established itself as a clearly successful product, PC analysts are imagining that it needs to become more like a conventional PC, an incredibly backward perspective that isn't supported by any facts.

When the only fastener you're familiar with is a nail, a high power screw gun doesn't appear to make any sense.

Apple defied expectations to consolidate its power in smartphones

Now consider the parallel trajectory of iPhone. Analysts regularly expected to see iPhone sales plateau and then begin falling off as the market began to react in competition to the novelty of iPhones. An initial wave of second attempts by Palm (webOS), Nokia (Open Symbian and MeeGo), RIM (BlackBerry 10) and Microsoft (Windows Phone) all failed to do this.

Google's Android, essentially the second wind of Sun's JavaME, did little more than replace high volume, low end Java phones with high volume, low end Androids (and Android is itself is little more than an improved JavaME, with its technical direction appropriated from iOS).

Apple has grown dramatically alongside Android. But rather than eating into iPhone sales, Android is primarily converting simple-phone users into smartphone users, acting as a pair of training wheels that contribute toward the growth of iOS as entry-level users transition upward and switch to iOS, the high-end market leader. This isn't just theory, it's reflected in switcher rates, Average Selling Prices and usage models, and is evident in the profitable outcome for Apple. Android isn't competition for iOS, it's a feeding tube. Android isn't competition for iOS, it's a feeding tube

Instead of being effectively disrupted by cheaper phone competitors, Apple's iPhone has disrupted the PC industry's status quo— for all PC makers apart from the world's largest PC maker, which has continued to grow in volumes, revenues and profits. For some reason, both the disruptor and the sole survivor of PC-Armageddon are the same company: Apple.

Apple conquered the profits and volumes of the PC industry while also shaking the core foundations of the conventional PC loose with iOS. Nobody predicted that would happen, but it just keeps happening. Rather than recognizing this, analysts keep kicking their prediction of Apple's doom down the road. In their minds, it's perpetually a quarter or two away, regardless of whatever Apple actually reports in its current quarterly earnings.

Eight years after Apple's iPhone first went on sale, its share of global smartphone profits has reached an astounding 94 percent.

Back in 2011, Apple was taking 52 percent of the smartphone industry's profits. In 2012, iPhone reached 75 percent and last year it took 87 percent.

That's the opposite of the claims predicted by IDC, which have regularly insisted that Apple's market share was receding or would be overtaken by Microsoft. It also flies in the face of "research" by Strategy Analytics, which once erroneously claimed that Samsung had surpassed Apple in profitability, and suggested that Apple's era was now over— a "story line" that even convinced the Wall Street Journal to play along in anointing Samsung as the next Apple.

Today, it appears that the smartphone market is now slowing down, making it impossible for volume leaders (like Samsung) to maintain growth simply based on shipping more units. That is having a negative impact on virtually everyone in the market— apart from Apple, which continues to make more money (and even sell more iPhones) despite an overall maturing market.

That shouldn't even be surprising because it already happened with PCs, where there's been little to no overall market growth since the iPad appeared in 2010. However, Apple itself has seen its Mac sales grow dramatically in both units and revenues, contributing to an increasingly large slice of the PC industry's total profits.

The same thing is happening with tablets. Despite a temporary bubble in global unit shipment volumes that pushed Apple's "market share" downward, there's only one company that sells tablets at a profit in large volumes. That was true before tablet growth leveled off last year, and it remains true today.

The secret to Apple's success

Rather than observing and documenting Apple's systematic pattern of success, market analysts continue to predict an end to it. That's curious because nobody even considered predicting an end to the overwhelming market power of Microsoft's Windows. However, there's a common thread behind Apple's success and Microsoft's fall.

The core of Apple's commercial success is pretty simple: Apple is focused on profits, not sales volumes.

Achieving profitability involves more than simply building in a high profit margin. In order to be profitable, Apple has to deliver a desirable product consumers will willingly pay for. That has meant investing in big initial gambles, then relentlessly innovating (or acquiring) new components that can perpetuate demand for its products at a sustainable margin.

This is not really a secret; it was also the core of Apple's success with iPods, which similarly allowed the company to enter and quickly rise to dominate a new market with entrenched competition— and then fend off new assaults. While Apple's profitable rise to the top of MP3 players, phones, tablets and now watches is undisputed, the part that many seem to be missing is that once on top, Apple acquires an entirely new set of powers.

Analysts seem to only pay attention to the economies of scale that enable high volume producers of low-end commodity products (like HP and Samsung) to drive prices down, attracting higher volumes of customers. However, the end game for these companies is disastrous: they're now stuck with customers who demand perpetually lower prices, which kills their ability to invest and innovate, simply because their margins are too tight to afford liberal investment in the next big thing.

Apple follows a completely different strategy: identifying key technologies that can drive premium sales, then developing these in house or acquiring them (often at great expense) and amortizing the cost of these technologies across increasing volumes of sales— attracted by user satisfaction, not by low prices. Rather than ending up at the bottom, Apple builds an ever larger base underneath itself, one that is loyal and hungry for more premium products, and willing to pay for them. While investors remain in awe of Amazon and Google for rapidly investing in moonshot ideas that may at some point generate profits, Apple is building a self-sustaining engine that generates incredible profits while driving itself toward new business opportunities

While investors remain in awe of Amazon and Google for rapidly investing in moonshot ideas that may at some point generate profits, Apple is building a self-sustaining engine that generates incredible profits while driving itself toward new business opportunities.

The secret is easy, delivering is hard

The idea of selling desirable, premium products with healthy margins is the basis for every luxury manufacturer— from cars to clothing to high-end watches, all of which dominate their broader market in profitability.

In fact, when the Old Apple was struggling to sell high volumes of low-end Mac Performas in the mid 1990s, it paid rank and file analysts to come up with a turnaround strategy and got the same advice (to focus on building high quality, profitable products instead)— even before Steve Jobs returned to make it happen.

Samsung's Galaxy line, Microsoft's Zune and Surface brands and even Google's failed Silver initiative all show that Apple isn't the only company to have stumbled onto the rather obvious reality that profits come from higher-end products, not low-end commodity ones.

However, unlike the short-lived 3 year flash of Samsung's peak Galaxy profits or the struggling death throes of Microsoft's devices or the complete failure of Google to ever profit from hardware, Apple has been profitable for virtually all of the last 40 years, with the last fifteen showing a particularly massive ramp.

Delivering profits aren't easy though. Even senior Apple executives who helped create the iPod have been unable to replicate Apple's success outside of the company, notably Jon Rubinstein (who attempted to deliver an iPhone competitor at Palm in the creation of webOS) and Tony Fadell (who launched Nest Labs as an Apple-like hardware maker).

It's obvious that companies need to be profitable. What's less obvious is how to identify windows of opportunity, how to effectively bet big on products that will pay off sustainable profits, and then how to turn a revolutionary, profitable product into a business that can fend off new rivals. Apple has perfected this cycle.

The real secret is that Apple knows what it's doing, as is obvious from the failure of others to achieve similar success, even when slavishly copying Apple's end products.

Apple is not a cycle of lucky hits

Despite a string of massively successful products from Apple over the last 15 years, Wall Street continues to be pessimistic of Apple's future chances at success. If you view Apple as a studio behind a series of hit movies (iMac, iPod, iPhone, iPad and Apple Watch), it makes sense to fear that Apple's next film might be a flop that could take down the entire company. However, Apple is not run as a hit-driven movie studio.

It wasn't the luck of a smart product invention that launched iPod in 2001. It was the platform of a loyal demographic that Apple had built around the Mac, the ecosystem it was preparing in iTunes, and an operational savvy that lined up efficient production and distribution.

It wasn't just Steve Jobs' genius that delivered iPhone in 2007. It was a technological legacy of OS X that Apple had invested in over the past decade, the mobile device design legacy of the iPod that Apple had refined over the previous five years, along with years of mass production experience and incremental advancement of the iTunes ecosystem.

Apple's hit products weren't like hit movies that happened to find an audience. They are more like formulaically successful products from Ferrari, Prada or Rolex that have hungry audiences waiting in anticipation. Apple's hit products weren't like hit movies that happened to find an audience. They are more like formulaically successful products from Ferrari, Prada or Rolex that have hungry audiences waiting in anticipation.

In contrast, when Microsoft decided to build the Zune, it simply went to Toshiba and tweaked an existing MP3 player that had never sold well, then paired it to a brand new ecosystem that nobody had ever used before.

Ironically, this was very similar to the failed strategy that Novell, IBM and Sun had earlier used in their dead-end, app rebranding efforts to compete against Microsoft's Office suite. Like Zune, by the time those suites entered the market, the market leader had grown too entrenched to defeat half-assedly.

Google's Nexus products followed a similar Zune strategy of creating rebranded, placeholder competitors that appeared to have legitimacy as products, but which wouldn't sell well and weren't profitable. Even if Google had any expertise in marketing and selling hardware, it would not have been able to build devices in volume at a profit.

Even Sony, Samsung, LG, HP, Dell and other experienced hardware makers have trouble earning razor thin profits from mass-produced electronics manufacturing. And consider Microsoft's Xbox 360, which the company lost billions of dollars on for years right up until it was obsolete, while writing off another billion in warranty expenses due to mistakes made in manufacturing that resulted in an incredible fifty-two percent return rate.

The alternative strategy to placeholder vanity products like Surface and Nexus is to produce massive numbers of different products to cover every conceivable buyer in a given market, as typified by HP and Samsung. Samsung makes dizzying numbers of phones and tablets, each with different components and specifications, screen sizes and tweaks required to deliver an Android update. HP does the same for its PCs and tablets, even spanning multiple operating systems. It turns out this is not very profitable.

The massive Apple engine

By focusing on streamlined profitability, Apple delivers regular hits and very few significant misses. It also benefits from massive economies of scale. Rather than building hundreds of wildly different iPhones, Apple has historically sold three basic models (this year's and the two prior's), a strategy that enables it to focus its marketing on driving high sales volumes of its high-end, newest model. That delivers major cost advantages in procuring advanced components at favorable prices, achieving profitability while driving down the cost of owning futuristic technologies.

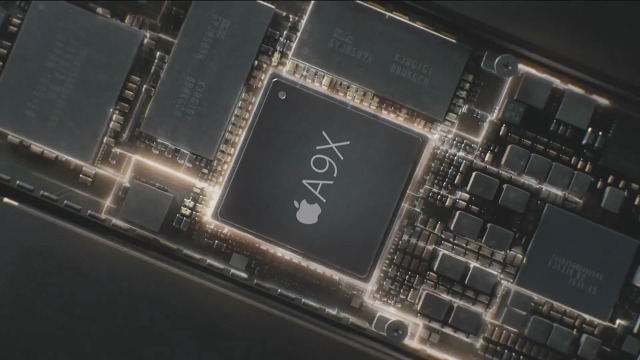

That profitability finances the development of ever faster and more efficient chips and other expensive components, making it increasingly difficult for outsiders (or even industry incumbents) to steal away its customers. Apple's massive volumes of iPhone and iPad sales, concentrated into a few models, also greatly simplifies the tight integration of its software.

While analysts look at iPad Pro and compare it as an equal with Microsoft's Surface Pro 4 or even Google's Pixel C, Apple's new iPad shares a tablet platform that consistently sells over 50 million units per year, has a vast installed base and a strong ecosystem. Apple knows how to orchestrate the construction of tens of millions of devices, and has years of experience in lining up massive component deals. Across many years of attempts, neither Microsoft nor Google have ever released a commercially successful tablet even on par with the original iPad.

And if you carefully parse the more in-depth reviews, you'll find that both the Surface and Pixel lines have major, glaring software problems. Again, it's like comparing Star Office to Microsoft Office: that comparison only existed in the minds of reviewers who wished that Microsoft had some real competition, back at the apex of its monopoly.

The fact that IDC and other groups are talking up the prospects of completely phony placeholder products with zero shot at relevance says a lot about actual competition in the tablet market. Every year we are subjected to similar comparisons of iPhones against Nexus placeholders, or other flagship Android phones that make up a minority of the huge volumes of mostly low end devices shipped by Samsung, Xiaomi, Huawei or HTC.

Apple's consolidation of profits means that most of the money from global sales of PCs, tablets and smartphones is being reinvested into proprietary silicon and custom components that only Apple benefits from, even though Apple doesn't have anywhere near a monopoly over unit sales in any market. That positions the company with the ability to develop new software (such as Metal) that drives exclusive benefits across its product line, as well as developing new product categories (like Apple Watch) that even large competitors will find it hard to effectively compete against.

Five years after introducing iPad, despite the appearance of many competitive efforts, there still aren't any tablet producers reporting significant profits of any kind, let alone being in the ballpark of Apple's +$20 billion in annual iPad revenues. Even more telling, the nascent smartwatch category was blown out of the water by Apple Watch in just its first few quarters. And while smartphones have been around for more than a decade now, there's only one that's been consistently profitable over the long term.

Bad news for Apple's competitors

That's really bad news for Apple's current competitors, and even worse for any new ones hoping to enter the market. Attempts by Firefox OS, Sailfish or Samsung Tizen to enter a mature market where there is only one real aspirational brand for users and only one serious development platform for developers highlights the likelihood of a new phone platform bursting onto the scene and offering Apple some significant competition. Even Microsoft, Blackberry and HP can't make a dent, despite being backed by companies with billions in revenues.

While many market research firms have worked diligently to distract away from the reality of Apple's empire-building profitably over the past decade, the company is now positioned to make it even harder for rivals to offer any challenge. In 2006, Apple was much smaller than Nokia and several other top phone makers, and in 2010 it was much smaller than HP and several other top PC makers. It's now among the top largest companies in every category that it operates by sales volumes, let alone being the most profitable.

Apple assembled the first iPod and iPhone largely using off the shelf components and technologies. It now creates custom components across the board, and has a series of Apple-only technologies and development platforms. Apple now has the power to radically shift industries simply by switching suppliers or changing the types of components it uses.

Unlike the PC heavyweights of the last two decades, Apple also now controls its own OS and apps platform. HP and Dell were always at the mercy of Microsoft's initiatives, just as Samsung, HTC and Lenovo are dependent upon Google for Android. The frustration voiced by these platform licensees is palpable, as is the frustration of the platform developers with their licensees. Both are fighting for increasingly small scraps of revenues that can be derived from adware, user behavior analysts and other layers of marketing, which further degrades the value of their composite products.

A upcoming new decade of even worse news for Apple's competitors

While Apple has remained wildly successful over the past decade as an underdog, first in PCs, then in phones and tablets and now in watches, it's now entering a new phase where it is the dominant leader in virtually every category that it operates. There are a number of new opportunities where Apple can try to replicate its underdog-disruptor success of the past, particularly in enterprise sales, automotive and IoT / HomeKit integration. However, Apple's current position atop the consumer computing industry gives it a new set of powers to exercise. Apple's current position atop the consumer computing industry gives it a new set of powers to exercise

Across the 1990s, Microsoft achieved a similar position of power and used it to steal all the good ideas its competitors were developing. After initially being broadsided by the web— at the time led by Netscape and Sun— Microsoft belatedly introduced its own web browser and server and immediately took a majority share of that emerging market. Microsoft also appropriated Apple's QuickTime (even stealing the company's code), and ripped off every emerging new hardware and software idea as it surfaced.

The only thing that blunted Microsoft's copy-killing were antitrust lawsuits that alleged that the company was abusing its monopoly power over the PC industry. Apple doesn't have a monopoly. Its majority of profits come from a subset of the overall market for PCs, phones, tablets and watches, all of which have lots of active competition.

Now consider, given the market power and capital that Apple currently has, how easy it will be for the company to identify successful emerging trends in hardware product categories and software, and quickly act to effectively out-rival would-be disruptors. This appears to be a lot easier task than fighting from the bottom, as Apple had been successful doing.

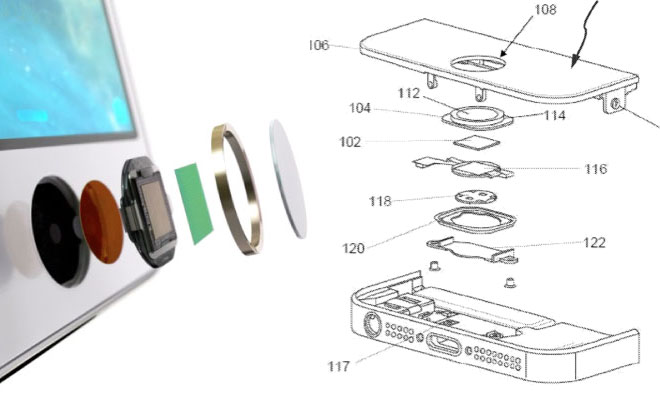

In fact, we have some good examples of this already. Apple wasn't first to fingerprint scanners or NFC payments or voice-based assistants or large-sized phones or smart watches or modern tablets sold with an active stylus. In every case, Apple didn't just copy what its competition was doing, but instead dropped significant coin figuring out how to do the same thing significantly better, in a way that would make its own products even more attractive to buyers.

Apple paid more attention to security and usability, and subsequently delivered something that was far better than its rivals. It was also often late to market— in some cases many years late— but that didn't affect its ability to win.

Before Touch ID, Motorola and other Android phones had bolted on a fingerprint reader with no specific purpose that was clumsy to use and didn't work well. Before Siri, Google experimented with voice-based services. Years before Apple Pay, Google launched its own NFC Wallet, although without similar security and privacy tools, and restricted to a narrow set of accounts. Before iPhone 6, Samsung and many others had built large-screen phablets, although using poor quality PenTile displays with pixel counts their processors weren't equipped to handle. Before Apple Watch there were a series of puzzling wrist-based computers that looked terrible and didn't do anything useful. Before iPad Pro, Microsoft's Surface explored the use of a digital stylus, although it lacked tablet apps and made too many compromises to effectively sell in volume across its first three years.

Across just these few examples, Apple continued earning higher profits while rivals introduced new, emerging technologies; Motorola, Google, Samsung and Microsoft spent billions of dollars developing products and infrastructure that were blindsided by Apple. Motorola's purchase of sensors from Authentech effectively helped fund the the development of Touch ID. Google paid to build out NFC reader infrastructure in the U.S. that paved the way for Apple Pay. Samsung helped create market demand for large displays that benefited iPhone 6, and its Galaxy Gear watches built anticipation for Apple Watch. Microsoft has spent billions advertising the idea that even business users don't need a PC laptop because tablets can be sufficiently powerful.

Apple isn't just syphoning profits off the top of the tech industry; it's delegating a lot of the most expensive, low-return expenses to its competitors, from advertising to infrastructure to component development. Apple isn't just syphoning profits off the top of the tech industry; it's delegating a lot of the most expensive, low-return expenses to its competitors

At the same time, Apple is using its own capital to obtain high volume discounts on customized components and to invest billions into research and development that is out of the reach of most competitors. A perfect example is Apple's five years of development in A-series chips, including custom ARM cores that are unavailable to (and not even well understood by) its rivals.

Google and Microsoft have delegated their platforms' core CPU and GPU development to Intel, Nvidia and other firms. Developing new chips is expensive and risky; Texas Instruments and Nvidia have exited the smartphone market entirely, and Intel has struggled to remain relevant in mobile even after paying manufacturers billions of dollars to use its mobile chips.

Even Samsung, which has long manufactured Apple's A-series chips, sat back and watched Apple develop its own proprietary core SoC IP that outpaced its own abilities. At this point, Samsung's capacity to drive SoC development with fat Galaxy profits is over, because unit sales of high-end Galaxy sales warranting an expensive new chip are not only down, but no longer generating the fat profit margins capable of sustaining long term, expensive IP development.

Analyst Ben Bajarin recently predicted that "Samsung will be out of the smartphone business within five years," based largely around the fact that Samsung's phone business has now reached an Average Selling Price of $180, making it increasingly impossible to fund new generations of high-end chips suitable for premium devices that it is no longer capable of selling at a sustainable margin.

A better question might be: what's the next big thing for Amazon, Microsoft, HP, Intel, Nvidia, Samsung, Qualcomm and Google, because they're all up against a big engine with lots of capital and a proven ability to deliver hits while generating profits.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

49 Comments

If Samsung is going to be out of the smartphone business in 5 years what hope does anyone else have?

Every now and then, a breath of fresh air is appreciated. Thanks, AppleInsider!