Apple's surprise decision to launch its own Maps service in iOS 6 caught Google off guard in the same manner that Google turned the tables on Skyhook Wireless just two years ago.

Apple pulls the rug on Google's Maps

The announcement of Apple's new iOS 6 Maps at this summer's Worldwide Developer Convention took Google by surprise, because Apple still reportedly had a year remaining in its contract with Google to provide maps for iOS.

The surprise introduction of Apple's own Maps for iOS 6 gave Google very limited time to bring its own version of Maps to iOS. But Apple didn't just want to compete with Google. It wanted to show off an amazing Maps experience that raised the bar and would leave Google scrambling to port a good enough version of its own maps to compete with it.

Google faced the task of not just porting its existing Android Maps version to iOS, but improving upon its features and appearance to match Apple's own version. That would logically include matching the 3D features of Flyover, which Google already has in a limited fashion on iOS in the form of its Google Earth app.

Integrating Earth's 3D overview features into Maps Navigation would involve additional complication given that the two products draw from different code bases.

Google Earth also has the same kinds of 3D rendering glitches that Apple's Flyover has (the Golden Gate Bridge doesn't have a highway running beneath it as Earth's rendering suggests, below top, contrasted with Apple's Flyover view below it), making it impossible for Google to ridicule those kinds of errors without denigrating its own product at the same time.

Earth is also less detailed, and its images are older than Apple's. This Google Earth view of Doyle Drive in San Francisco (the Highway 101 approach to the Golden Gate Bridge) predates any construction, despite work having started in 2009. Apple's version shows advanced construction, although it too is several months old.

Additionally, all the work to produce a new Goggle Maps Navigation+Earth for iOS would need to be paid for by ads (just like Google's free Chrome browser or YouTube app for iOS), because few iOS users would be likely to pay anything substantial to replace Apple's own Maps with Google's version. In contrast, Apple's software development is funded through profitable hardware sales.

If Apple had given Google advanced notice of its intent to take Maps solo, Google could have devoted its efforts toward introducing its own Maps alternative that matched Apple's features and added more of its own right at the launch of iOS 6.

However, Apple's surprise announcement left Google with no recourse but to heap complaints upon Apple's new Maps while having nothing to offer as an alternative apart from its own limited web app. Meanwhile, iOS 6 immediately shifted users (and all third party apps) to Apple's own maps servers while Google was left vending its valuable information for free via in an inferior web-based interface.

By the time Google can release its own Maps app for iOS 6, Apple will have had months to work out its place name bugs and visual 3D glitches from its own version.

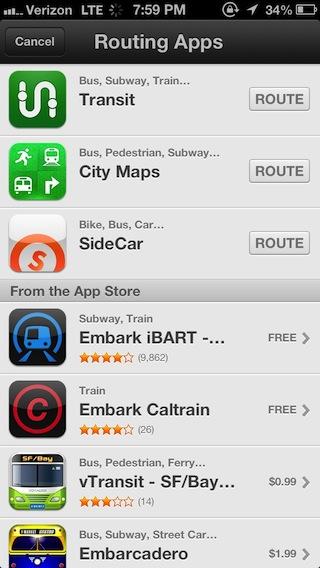

Additionally, millions of users will have grown accustomed to using Apple's revamped interface, its Siri integration, Yelp integration and its support for a range of novel third party routing apps to obtain everything from transit and water taxi routes to ride sharing services.

Skyhooked on its own petard

How big of a deal is it for Apple to be getting (and Google to be losing) exclusive access to millions of iOS Maps users placing millions of queries and making millions of crowdsourced reports of traffic, place name corrections and other direct and/or automated feedback?

Consider that in early 2010, when Skyhook Wireless inked a deal with Motorola another Android licensees to use its own WiFi-based geolocation features in place of Google's Location Services, Android product manager Steve Lee stated, in emails revealed through subsequent court proceedings reported by the New York Times, that the deal "would be awful for Google because it will cut off our ability to continue collecting data to maintain and improve our location database."

Google subsequently informed its licenses that using Skyhook for their WiFi geolocation would invalidate their promise to uphold "Android compatibility," an opinion Motorola initially described as "unfounded." One month later however, Motorola informed Skyhook that their agreement had been terminated because of Google's determination that it "renders the device no longer Android Compatible."

Skyhook subsequently sued over Google's strong-arming to stop its geolocation service deal with Motorola, and additionally accused Google of stealing its technology. The real issue, Google's lawyers stated in response, was not Android compatibility but rather that Skyhook had infringed upon Google's "contractual rights to collect end-user data."

If Google felt threatened by a startup making deals with Samsung and Motorola on select Android smartphones, imagine how the company feels about instantly losing access to collect map queries and traffic data across tens of millions of Apple's iOS users.

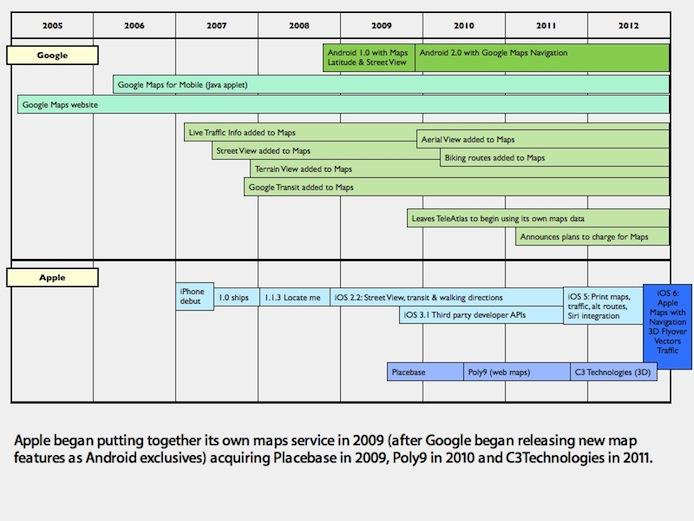

Understanding the history behind mobile maps development at Apple and Google provides clear insight into not just why Apple created its own Maps for iOS 6, but also how likely the new app will be able to solve its various outstanding issues.

Apple's history with Google Maps has been widely distorted to the point where some pundits have incorrectly asserted that Google initially wrote the Maps app for iPhone, while others have announced that Apple will need to hire tens of thousands of employees just to match the staffing that produced Google's Maps (much of which has been devoted to laborious Street View photo collection efforts).

Because Apple's new Maps isn't a simple subject, the answers— and the important questions— regarding its outstanding issues are not simple either. Both require some background information about where they came from and why, and the business models that are intended to support them.

Google, leader of web maps

Google's dominant position in mobile maps originated with Apple, but when the iPhone first appeared in 2007, Google had already established its web-based maps as the leader in online mapping.

This was largely due to its novel use of AJAX web technologies to present and display easy to peruse maps and satellite imagery, a project that developed as an outgrowth of Google's 2004 acquisition of Where 2 Technologies.

Competing web-based map vendors simply couldn't match the complex layers of web kluge (complex JavaScript, iFrames, translucent PNG images and Adobe Flash) Google had created to force the humble web browser to work as a near desktop-quality mapping application.

In less than three years of Google Maps development, competing conventional web maps had all fallen behind to a very distant second place, leaving Google's web talents virtually uncontested. That made working with Google's Maps API a natural choice for Apple in developing the iPhone.

Apple trades Java for Cocoa

However, Google's mobile maps strategy of 2006 was built around Java, which was at the time the nearly universal platform for cellphones capable of running any type of applets (Symbian, Windows Mobile, Palm and Blackberry could all run Java apps).

Apple wasn't interested in supporting Java on its new iPhone however, instead relying exclusively upon its own Cocoa Touch developer tools to deliver custom native apps that were essentially scaled down Mac apps (rather than Java middleware code running on a Virtual Machine hosted by the phone's core OS).

Rather than working with Google to build a custom web app for iPhone, Apple developed its own native Maps app for iPhone that obtained 2D street and satellite images using Google's open Maps APIs, along with driving, walking and transit directions that followed.

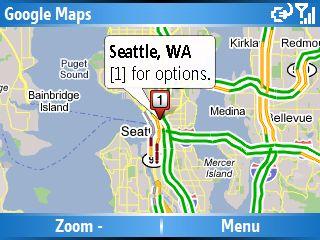

This allowed Apple to deliver a spectacular Maps experience unlike any ever seen before on a mobile device (compare Google's Maps for Mobile running on Windows Mobile in 2007, below).

Apple's new Maps application was so good it made Google's Java-based "Maps for Mobile" applets look downright clumsy in comparison.

The new Maps, alongside the iPhone's exceptional Safari mobile browser, Mail and other bundled apps, enabled Apple to trounce the overall experience other smartphone vendors were selling, resulting in a mad scramble by Nokia, RIM, Microsoft and Palm to overhaul their aging mobile platforms in feverous attempts to catch up.

Android takes its direction from iPhone

None of these mobile platform companies, which ruled the roost when iPhone debuted, are even considered serious contenders today. They were summarily replaced by Apple's iPhone and a new effort by Google to rebrand a revamped and optimized version of Java/Linux as "Android," an initiative that's younger than the original iPhone Maps app itself.

Google initially hoped to launch Android as a free alternative to Windows Mobile and as a more coherent replacement for Java/Linux (a fragmented mess of platforms where every manufacturers' phones had their own VM with more quirks and bugs to work around than a web browser in the late 1990s).

Android was planned to give Google a competitive footing in smartphones at a time when Microsoft was threatening to use the launch of Windows Vista to push Google and its web search right off the Windows PC desktop. While Microsoft was ultimately unsuccessful at taking Google's search business away on the PC, Google didn't want to take any chances at risking a similar threat in the rapidly emerging market for smartphones.

After seeing what Apple had done with iPhone however, Google began shifting its Android strategy to become the "open alternative" to iOS, attracting attention from developers and hobbyists that didn't like the idea of Apple's centralized control of apps and media on top of the company's "whole-widget" control of both the iPhone's hardware and OS software.

While initial releases of Android were largely limited to the hobbyist community, Apple's rapid ascent in smartphones enabled it to surpass Palm and Windows Mobile in its first two years on the market, while catching up to RIM's once blockbuster Blackberry business.

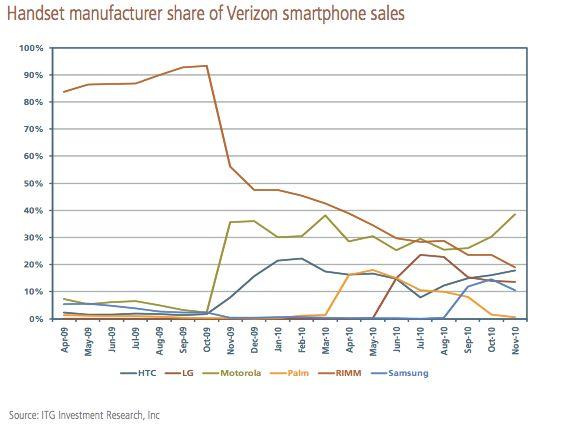

In the U.S., Verizon had grown concerned by Apple's exclusive partnership with AT&T. The iPhone had turned around Cingular, which had been a struggling confederation of GSM carriers, and relaunched it into a serious new nationwide mobile competitor rebranded as AT&T and armed with the world's most talked about smartphone.

By the end of 2009, Apple's iPhone had advanced to the point where Verizon had given up on RIM's efforts to match it with new Blackberry models. Instead, Verizon decided to partner with Google's Motorola licensee to launch Android 2.0, finally considered ready for mainstream use.

Unsurprisingly, the key feature of Android 2.0 was Google's new Maps Navigation, which leveraged Google's maps prowess to beat the iPhone in delivering built-in turn-by-turn directions with voice commands, local search and live traffic reports.

Google had also made it clear that it was competing against Apple, opening mocking the company while comparing it to North Korea, and in various respects presenting itself to its giddy audience of admirers as a hero that had already won the smartphone wars before even starting to battle.

At the same time, Google also expected Apple to continue helping it as a close partner in the mobile space, publicly stating that it expected Apple to quickly adopt Android 2.0's Maps Navigation features for use on the iPhone. That never happened however.

According to a report by John Paczkowski of the Wall Street Journal "All Things Digital" blog, while Google was publicly stating that it hoped Apple would adopt its Navigation features on iOS, it also wanted to keep voice navigation exclusive to Android, leaving Apple's platform in "a clear disadvantage in the mobile space."

Instead, Apple initiated a series of map-related acquisitions that made it obvious that it intended to develop its own mapping service independent from Google. Three years later, about the same period between Google's first map acquisition and the debut of widespread mobile maps, Apple introduced its own Maps for iOS 6.

This all happened before

This isn't the first time a technology company has started competing with a partner. Google itself left TeleAtlas in 2009 to rely upon its own maps, and broke ties with Skyhook after it had collected enough WiFi data to perform its own geolocation. It likely should have anticipated that Apple could do the same thing to it on iOS.

It certainly isn't new for Apple, either. When Microsoft stopped active development of Internet Explorer for Mac, Apple created its own Safari browser, and set up an open source project that now powers the overwhelming majority of mobile devices and has recently even surpassed Internet Explorer on the desktop.

When Microsoft let Office for Mac fall behind, Apple similarly launched its own iWork productivity suite, which has not only established itself on Mac (where it destroyed Microsoft's ability to charge up to $500 for regular Office updates), but has made its way to iOS to become the world's top grossing mobile productivity suite.

After Adobe stopped caring about the Macintosh platform, Apple focused on HTML5 and H.264 and backed away from Flash, a stance that singlehandedly terminated Flash on mobile devices (something that Adobe's much publicized Flash support for Android couldn't prevent) and marginalized its necessity on desktop systems as well.

Apple's initiatives haven't always been flawless slam-dunk successes, however. MobileMe Galleries, iWeb, Ping and iWork.com are just a few examples of its abandoned initiatives. The question is: is the new Maps a Safari or a Ping?

Strategically, of course, Apple needs iOS 6 Maps to succeed far more than its halfhearted stabs at free online services. The company's efforts to launch iWork, Safari and HTML5 were categorically ridiculed by critics at launch, too, making the campaigns to mock Maps nothing new.

Like iPhone 4's Antennagate and the criticism of Siri at the launch of iPhone 4S, competitors' complaints about iOS 6 Maps are likely to have little negative impact on demand for iPhone 5. What competitors should focus on is matching or exceeding Apple's efforts to global, modern vector maps, 3D visualizations and other new features to mobile users.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

108 Comments

I'm sure Google can't believe their luck, that Apple would actually create a key weakness in the Apple platform. Hopefully they work it out quickly, but I guarantee Google is in no rush to help Apple out of this bind by releasing a standalone app.

Daniel, this borders on a RoughlyDrafted Rant.... It provides interesting backstory and opinion, but not as much 'insider' information. It's interesting, just not sure which Banner it should fly under.

Frankly, I really don't care how Google feels about this.

They've been given the boot. It's all Apple's baby now. In the long term, Google isn't needed.

It's been rumored for at least 3 years that Apple has been working on a maps. I knew it. Everybody knew it. How, then, is It possible that Google was blindsided by this? I'm not buying it.

[quote name="AppleInsider" url="/t/152918/how-google-was-skyhooked-by-apples-new-ios-6-maps#post_2199140"]If Apple had given Google advanced notice of its intent to take Maps solo, Google could have devoted its efforts toward introducing its own Maps alternative that matched Apple's features and added more of its own right at the launch of iOS 6. [/quote] Right. And pigs can fly. Google has made it clear for years that iOS users are second class citizens. Apple did what they had to do.