While rumors have long claimed that Apple has plans to replace Intel's x86 chips in Macs with its own custom ARM Application Processors, MacGPUs are among a series of potentially more valuable opportunities available to Apple's silicon design team, and could conceivably replicate Apple's history of beating AMD and Nvidia in mobile graphics processors— and Intel in mobile CPUs.

Building upon How Intel lost the mobile chip business to Apple, a second segment examining how Apple could muscle into Qualcomm's Baseband Processor business, and a third segment How AMD and Nvidia lost the mobile GPU chip business to Apple, this article examines how AMD and Nvidia could face new competitive threats in the desktop GPU market.

Apple's aspirations for GPU (and GPGPU)

In parallel with the threat Apple poses to Qualcomm in Baseband Processors, there's also a second prospect for Apple that also appears to have far greater potential than ARM-based Macs: Apple could focus its efforts on standardizing its GPUs across iOS and Macs, as opposed to standardizing on ARM as its cross platform CPU architecture.Apple could focus its efforts on standardizing its GPUs across iOS and Macs, as opposed to standardizing on ARM as its cross platform CPU architecture

Such a move could potentially eliminate AMD and Nvidia GPUs in Macs, replacing them with the same Imagination Technology PowerVR GPU architecture Apple uses in its iOS devices.

Today's A8X mobile GPU (used in iPad Air 2) is certainly not in the same class as dedicated Mac GPUs from AMD and Nvidia, but that's also the case with Apple's existing A8X CPU and Intel's desktop x86 chips.

Scaling up GPU processing capabilities are, however, conceptually easier than scaling CPU because simple, repetitive GPU tasks are easier to parallelize and to coordinate across multiple cores than general purpose code targeting a CPU.

Apple has already completed a lot of the work to manage queues of tasks across multiple cores and multiple processors of different architectures with Grand Central Dispatch, a feature introduced for OS X Snow Leopard by Apple's former senior vice president of Software Engineering Bertrand Serlet in 2009, and subsequently included in iOS 4.

A transition to PowerVR GPUs would also be easier to incrementally roll out (starting with low end Macs, for example) as opposed to the CPU replacement of Intel with ARM processors. That's because OpenGL enables existing graphics code to work across different GPUs, greatly simplifying any transition work for third party app developers; there's no need for a sophisticated Rosetta-style technology to manage the transition.

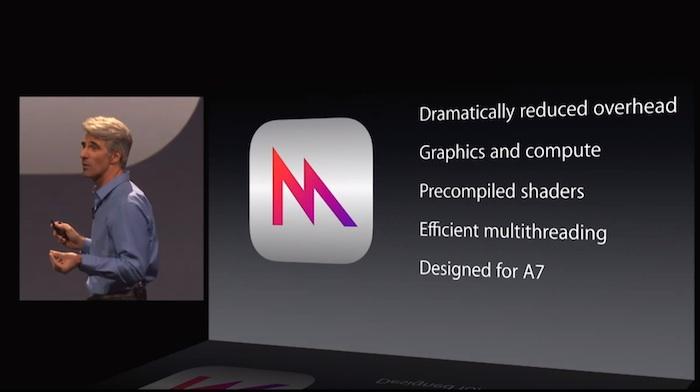

Metal to the Mac

By allowing developers to bypass the overhead imposed by OpenGL with its own Metal API, Apple can already coax console-class graphics from its 64-bit mobile chips. Last summer, a series of leading video game developers demonstrated their desktop 3D graphics engines running on Apple's A7, thanks to Metal.

Just six months earlier, Nvidia was getting attention for hosting demonstrations of those same desktop graphics engines running on its Tegra K1 prototype, which incorporates the company's Kepler GPU design adapted from its desktop products.

However, that chip was so big and inefficient it could not run within a smartphone even by the end of the year (and Nvidia has no plans to ever address the phone market with it). In contrast, with Metal Apple was showing off similar performance running on its flagship phone from the previous year).

With Macs running a souped up edition of the GPU in today's A8A (or several of them in parallel), Apple could bring Metal games development to the Mac on the back of its own PowerVR GPU designs licensed from Imagination.

Cross platform pollination

Apple already uses Intel's integrated HD Graphics (branded as Iris and Iris Pro in higher end configurations; they are built into Intel's processor package) in its entry level Macs, and currently offers both discrete Nvidia GeForce or AMD Radeon and FirePro graphics in its Pro models.

By incorporating its own PowerVR GPU silicon, Apple could initially improve upon the graphics performance of entry level Macs by leveraging Metal. Additionally, because Metal also handles OpenCL-style GPGPU (general purpose computing on the GPU), the incorporation of an iOS-style architecture could also be used to accelerate everything from encryption to iTunes transcoding and Final Cut video effects without adding significant component cost.

Both iOS and OS X make heavy use of hardware accelerated graphics in their user interface to create smooth animations, translucency and other effects.

Standardizing on the same graphics hardware would enable new levels of cross pollination between the two platforms. Certainly moreso than simply blending their very different user interfaces to create a hybrid "iOSX," which has become popular to predict as an inevitability even though it has little benefit for users, developer or Apple itself, and despite the fact Windows 8 is currently failing as a "one size fits all" product strategy for Microsoft.

The very idea of Apple replacing x86 CPUs in Macs with its own Ax ARM Application Processors would appear to necessitate a switch to the Imagination GPU architecture anyway, making an initial GPU transition a stepping stone toward any eventual replacement of Intel on Macs.

Not too easy but also impossible not to

Of course, some of the same reasons Apple might not want to leave Intel's x86 also apply to Nvidia and AMD GPUs: both companies have developed state of the art technology that would certainly not be trivial (or risk free) to duplicate.

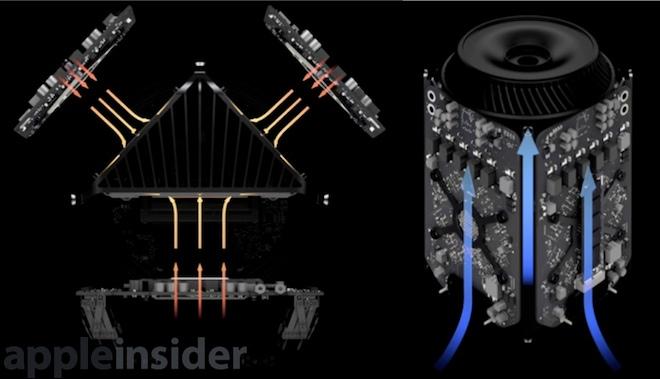

It is clear, however, that Apple is intently interested in GPUs, having developed a modern computing architecture for Macs that emphasizes the GPU as a critical computing engine, not just for video game graphics but system wide user interface acceleration and GPGPU.

Apple's new Mac Pro architecture (above) incorporates two GPUs and only a single Intel CPU on the three sides of its core heat sink, in clear recognition of the fact that GPU processing speed and sophistication are increasing at a faster pace than CPUs in general (and Intel's x86 in particular), and that multiple GPUs are easier to productively put to work and fully utilize compared to multiple CPUs.

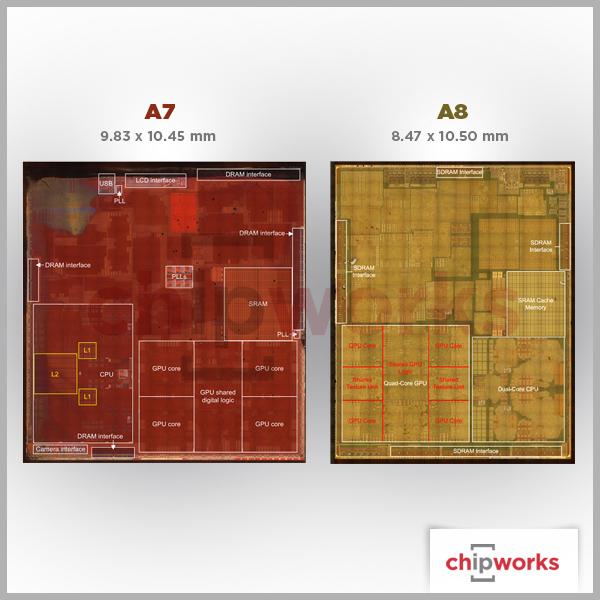

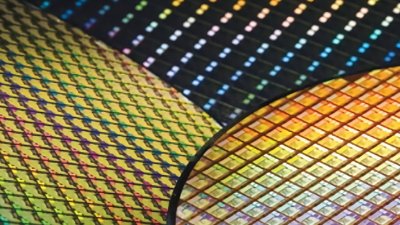

The same phenomenon is visible when you zoom in on Apple's modern Ax package: its GPU cores are given more dedicated surface area than the ARM CPUs, even on an A8X equipped with 3 CPU cores, as seen in the image below by Chipworks.

Monopolies resistant to change are now fading

All the speculation about Apple moving from Intel's x86 to ARM also fails to consider the potential for more radical change; why not move virtually all heavy processing on the Mac to a series of powerful GPUs and use a relatively CPU as basic task manager, rather than just replacing the CPU with another CPU architecture?

When the PC computing world was dominated by Intel and Microsoft, there was little potential for making any changes that might threaten the business models of either Wintel partner. PowerPC and AMD64 were opposed by Intel, while Unix and OpenGL were opposed by Microsoft. That left little room for experimenting with anything new in either hardware or software. When the PC computing world was dominated by Intel and Microsoft, there was little potential for making any changes that might threaten the business models of either Wintel partner

The two couldn't even rapidly innovate in partnership very well: Microsoft initiated its Windows NT project in the late 1980s for Intel's new i860 RISC processor, but was forced back to the x86 by Wintel market forces. Then a decade later Microsoft ported Windows to Intel's 64-bit VLIW Itanium IA-64 architecture, only to find the radical new chip flop after it failed to deliver upon its promised performance leap.

In the consumer market, Microsoft attempted to create a PDA business with Windows CE, and Intel invested efforts in maintaining DEC's StrongARM team to build ARM chips for such devices. The results were underwhelming (and the entire concept was largely appropriated from Newton and Palm, rather than being really new thinking for PCs).

Over the next 15 years of building the same formulaic x86 Windows boxes, Intel eventually grew frustrated with the failure of Windows even as Microsoft chafed with the mobile limitations of x86. Their solo efforts, including Microsoft's Windows RT using ARM chips and Intel's expensive experiments with Linux and Android have been neither successful nor very original thinking.

Thinking outside the PC

We are now at a new frontier in computing that hasn't been as open to change and new ideas since IBM first crowned Intel and Microsoft coregents of its 1982 PC, a product that wedded Intel's worst chip with Microsoft's licensed version of better software to build a "personal computer" product that IBM hoped would not actually have any material impact upon its own monopoly in business machines.

Apple's own meritocratic adoption of PowerPC was sidelined in 2005 by market realities, forcing it to adopt a Wintel-friendly architecture for its Macs (and for the new Apple TV in 2007). However, by 2010 Apple's volume sales of ARM-powered iPods and iPhones enabled it to introduce an entirely new architecture, based on the mobile ARM chips it had co-developed two decades earlier.

When it introduced the iPad in 2010, it wasn't just a thin new form factor for computing: it was a new non-Wintel architecture. While everyone else had already been making phones and PDAs using ARM chips, there hadn't been a successful mainstream ARM computer for nearly twenty years.

That same year, Apple also converted its set top box to the same ARM architecture to radically simplify Apple TV (below) and be able to offer it at a much lower price. The fact that the product already uses PowerVR graphics makes it a potential harbinger for what Apple could do in its Mac lineup, and what it will almost certainly do in other new product categories, starting with Apple Watch.

Skating to where the GPU will be

Microsoft maintained dominating control over PC games, operating systems and silicon chip designs between 1995 and 2005 by promoting its own DirectX APIs for graphics rather than OpenGL. Apple fought hard to prop up support for OpenGL on Macs, but the success of iOS has delivered the most devastating blow to DirectX, similar to the impact MP3-playing iPods had on Microsoft's aspirations for pushing its proprietary Windows Media formats into every mobile chip.

By scaling up Imagination GPUs on the Mac, Apple could reduce its dependance on expensive chips from Nvidia and AMD and bolster support for Metal and GPU-centric computing, potentially scaling back its dependence on Intel CPUs at the same time by pushing more and more of the computing load to its own GPUs.

Apple owns a roughly 9 percent stake in Imagination and— as the IP firm's largest customer— Apple makes up about 33 percent of Imagination's revenues. That makes Apple strongly motivated to pursue an expansion of PowerVR graphics, rather than continuing to fund GPU development by AMD and Nvidia.

This all happened before: How AMD and Nvidia lost the mobile GPU chip business to Apple— with help from Samsung and Google

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

52 Comments

It's a clever middle ground you've thought of. A way for Apple to save on components with minimal disruption to users. The only thing that makes me doubt it is that I think Apple are radical enough to go the whole hog (ARM CPU too) and just expect users to adjust.

Also, do Intel even sell CPUs without an onboard GPU? If not would Apple just let the iGPU sit dormant?

Moreover,

Apple needs to become just as Swift in the enterprise as it is in the consumer space on its way to the trillion dollar valuation.

Apple needs to own Enterprise Analytics + Cloud + Hardware + CPU + Software + DB + Services in addition to mobiles and wearables.

If the SIRI + Watson + Enterprise Apps effort with IBM works out well, Apple should consider merging with Big Blue to get the afore mentioned.

Dear writer: You know the PowerVR chip is Intel intergrated gpu, right? The only thing Apple did on A8x is CPU, and a small group of specialized circuit. Otherwise, we won't know it's a member of PowerVR 6XT

it's all nice and full of dreams but what I still want is an innovative product with full of great ideas and powers in a tiny convenient package to do HEAVY task with CG calculs, image rendering, signal analysis and high resolution image edition to summarize : the best work station with state of art technologies in still a reasonable price. The Mac Pro is already a forward thinking machine, with its own challenges, but it's still intel/amd based, and I don't see how Apple could provide something more powerful than that combo. ARM/powervr chips will improve of course, but so will intel and amd/nvidia desktops chips. Everything is "mobile" now, but we still need dedicated tools for creation. Maybe with attrition, Apple will force others companies like nvidia to give up even desktop, opening an opportunity to create a powerful new gpu but: - we don't have proof the architecture is scalable in a reasonable price - softwares does matter: OpenGL is not the end of everything: decades of x86 softwares, CUDA compatibility and so on. Even OpenCL is not that obvious, we need a full-featured OpenCL stack. of course, I'm all open to new radical computing and great new softwares, don't think I will not thrilled to learn new BETTER tools, but you ask (or dream) of a challenge even Apple couldn't take.

--------------------------------------------------

Sorry. But there are too many histrionics in these series of articles.

FIRST: Apple is NOT funding AMD or nVidia. Apple buys GPUs from them just like Apple buys its CPU/GPU chips from Samsung. The primary difference with the chips it buys from Samsung and those from AMD or nVidia is that Apple designs the chips that it buys from Samsung. AMD and nVidia design their own chips.

SECOND: Desktop chips - whether CPU or GPU - are hitting ceilings that limit their performance. It is called the laws of physics. Intel ran into that problem years ago when its CPUs hit a wall with their power requirements and heat output. In fact, the Mac Pro cannot take Intel's fastest chips because it doesn't have the cooling capacity to take the heat they generate. Similar problems occur with the GPUs. Today's top GPUs need TWO POWER SUPPLIES - one from the computer and another separate from the computer. The top desktop computers draw huge amounts of power. Think 500 to 1000 Watts. Run that 24/7 and you get a huge power bill. Should Apple do its own GPUs, it will run INTO THE SAME PROBLEM AND LIMITATIONS.

THIRD: In the mobile arena, Apple has been improving performance by targeting the low lying fruit, the easiest problems to solve. But when you look at the performance improvement curve of Apple's iPhone/iPad Ax chips, you see that with the A8, the curve is actually SLOWING DOWN. And this is because Apple has run into the laws of physics again. There is only so much you can do with limited battery power and limited cooing capacity on a mobile device.

FOURTH: Much of computing CANNOT be done in parallel. Word processing, spreadsheets, games, email, browsing, etc. are not parallel process tasks. Even Photoshop is limited to how many parallel processes it can handle. Apple has further been attempting to get users to use single tasks at a time in full-screen mode. Even on CPUs, after 2 CPU Cores, more parallelism by adding more CPU cores actually limits the top speed that any core can accomplish by increasing the heat output of the chip. This is why Intel has to slow down the clockspeed as more cores are added to chips. Thus, including further parallelism isn't going to make performance greater on any single task.

Should Apple want to tackle the desktop with its own custom GPUs, realize that they will always be playing catch up and will always be slower than those from AMD and nVidia.

The only reason for doing so is to save money in manufacturing. But that will have the side effect of lowering the quality of the User Experience.

For example: just look at the new Apple Mac Mini. It is now LIMITED to a 2-core CPU, rather than the 4-core of the previous model. It is SLOWER. But it is less expensive to make. The same limitations are found in the new Apple iMac with the 21-inch screen.

It is a sad day to see Apple going backwards in the user experience and choosing cheap components over higher quality components.

--------------------------------------------------