Less than a week before Apple unveils its latest "by innovation only" iPhones, the rumor mill and data mining is in full swing. However, the most important element of Apple's global success is not contingent upon a new feature introduction or perhaps a new product initiative, but rather the continued success of the software market that acts as the ecosystem binding together virtually everything Apple sells: the App Store.

Apple's App Store development presents a model of secrecy Apple follows to bypass its competitors and impress and surprise its customers.

Twelve years of the App Store's Walled Garden

Apple is on the cusp of publicly releasing iOS 13, but the platform's App Store is only twelve years old; it didn't launch until the second year of iPhone. While the iOS App Store is officially younger than iOS or iPhone itself, its development as an essential element of Apple's success in mobile software and devices actually began within iTunes as a conscious and very deliberate effort— even if Apple intentionally didn't clearly communicate its full plans to the media and its third-party developers all those years in advance.

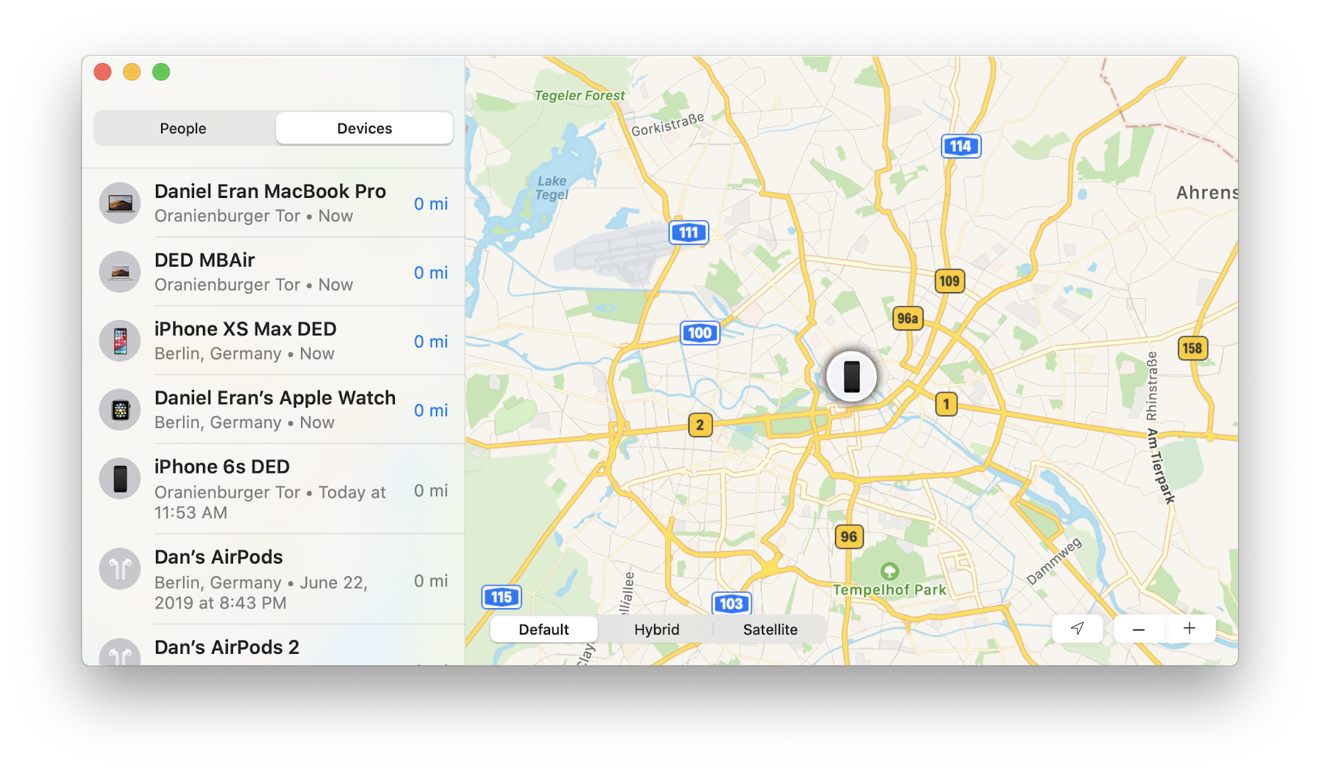

iOS 13 and macOS Catalina introduce the new Find My app, and appear to introduce new object tracking

iOS 13 and macOS Catalina introduce the new Find My app, and appear to introduce new object trackingAcross the first year of "iPhone OS," developers and even some customers clamored for access to write their native software for the new device. At launch, iPhone was limited to natively running only the software Apple shipped it with, which included a "real" desktop-class Safari web browser, and, notably, a Maps app that combined data from Google Maps with a new native mobile client app that was years ahead of any of the mapping apps that Google itself was delivering for PCs or mobile devices.

Back then, it was broadly assumed that anything Apple could do— from iPods to a full-screen smartphone and perhaps even a new tablet— could be quickly copied and improved upon by other much larger and more entrenched mobile and PC competitors. It might be hard to imagine today, but tech columnists largely believed at the time that Apple's App Store would have trouble competing against the app markets of Palm, Blackberry, Nokia and its global Symbian OS partners, and certainly Microsoft's Windows Mobile, which seemed to have such strong support among corporate enterprise users.

Yet as Apple's App Store gained ground among iPhone buyers, Palm, Blackberry, Nokia, and WiMo struggled to maintain what had appeared to be substantial head starts in offering their mobile software— despite their vast leads in market share and unit shipment volumes.

A big part of Apple's success came from carefully planning out of the deployment of its software platform as a life-sustaining ecosystem. And part of that planning required secrecy about the exact nature of Apple's plans, a reality that has continued in virtually everything else the company has done every year since.

Apple's secrecy in planning the App Store

Underlying concepts of the App Store— including its use of encrypted app signing that enabled both secure purchases and helped to limit software piracy— were developed and deployed years before Apple even shipped its first iPhone. In 2006 the company launched encryption-signed iPod Games as a way to introduce paid, secure software distribution within iTunes 7.

iPod Games were also unique in their leveraging of the vast installed base of iPod users to offer simple apps at a low price that could appeal to large audiences, making it feasible to develop games that could actually make money. Outside of Apple's iTunes, games for mobile devices were often attempting to sell at prices well above $15-25. Just as iTunes had revolutionized the sale of songs at $1 rather than demanding $15 or more for an entire album, Apple's iPod Games helped to discover a reasonable price point for mobile apps that would later be used in the App Store to tremendous success.

In its first year, a few million sales of iPhones would have trouble supporting an ecosystem of low-priced app sales comparable to the many tens of millions of potential buyers of iPod Games. Apple didn't offer any of its own iPhone apps for sale during 2007, and it announced to developers that the way to build software for iPhone was to create mobile web apps— which offered no real way to generate revenue the way iTunes songs or iPod Games had been.

A narrative developed that nobody at Apple had ever even imagined that iPhones would need anything more than the support for web apps that the company had introduced it with, in 2007. This story also maintained that Steve Jobs was adamantly opposed to third party native apps for iPhones, and that the introduction of the App Store came about only because third party developers were complaining about the issue and incessantly demanding to get the same level of access that Apple itself used to create game-changing mobile software like its bundled Safari, Mail, iTunes, and Maps.

Yet this is false. Jobs only publicly acknowledged Apple's plans to launch an App Store at the end of 2007, and Apple ultimately introduced it at the launch of "iPhone OS 2" in February 2008. But quite obviously, Apple didn't retrofit the design of iOS and implement the App Store in just the space of a few months after launching the iPhone, just because some vocal developers were demanding it. Apple had been working with a limited set of games developers to launch iPod Games for more than two years by that point.

Apple's competitors struggled to launch— or relaunch— their app markets over the space of years. If conceptualizing and building a successful App Store were something Apple could do within just a few months, it's hard to imagine that equally talented engineers at other companies simply found it impossible to launch their own within such a short period. The reality is that Apple didn't start thinking about building its App Store only after demands started rolling in. It just managed the public understanding of its efforts to make it look that way.

In February 2007, after the initial unveiling of iPhone but before its June launch, I asked Jobs at the company's shareholder meeting about Apple's plans to support third-party development on iPhones, specifically referencing both games and the niche needs of corporate enterprise developers to build their custom apps. His answer wasn't that web apps would be sufficient. Instead, he specifically noted that Apple was working through the factors of what would be required to support native apps without opening up security and privacy issues for users. He also referenced the work Nokia had been doing to deliver signed mobile apps for Symbian— even though Apple had already done this on its own in iTunes with iPod Games since 2006.

Apple wasn't trying to figure out what to do that late in the game. It was actively managing how much outsiders should know about its plans. As somebody who has closely followed Apple since the mid 80s, and who has been writing about everything the company did following its acquisition of NeXT in 1996, and with the privileged position of having been among the core group of outsiders allowed to observe what the company does at its developer and media events since 2014, I've developed an ability to see that much of what Apple appears to say is misdirection— or at least it offers the media enough rope to hang themselves on negative hype that distracts away from issues that are actually far more important than whatever problem they are seeking to portray as the thing that will doom Apple.

Apple's ability to focus outrage as a distraction

Apple's seemingly adamant public messaging during most of 2007 that web apps were the only supported way to develop third party titles for iPhone was true, but only because Apple hadn't yet finished App Store plans, and wasn't ready to talk about them yet. This may remind you of the opaquely boilerplate way Apple replies to queries about its acquisitions: "Apple buys smaller companies from time to time, and we generally don't discuss our purpose or plans."

It seems clear that part of the reason for Apple's App Store secrecy was to maintain a competitive edge against other mobile platforms that already had a lead in deploying their app markets. If Apple had detailed every element of its App Store plans well in advance, Palm, Blackberry, Nokia and Microsoft could have matched its efforts and likely could have delivered them first.

Instead, Apple only acknowledged that it was planning to deliver an official App Store late into 2007, just a few months before it would deliver it. During that short span, Apple could retain some elements of its plans as secrets that would be a surprise to both users and competitors, generating anticipation, buzz, and then an air of exclusive superiority. That is key to everything Apple does.

Strategic App Store secrecy allowed Apple to hold up web apps as a somewhat viable alternative to something else many developers and tech columnists saw at the time to be a critically important missing feature of iPhone: support for Adobe Flash content and applets and Sun Java. Throughout 2007, Apple remained rather quiet about its plans to support either, eventually stating it did not plan to support Java and would only "maybe" support Flash.

That was enough to convince even well-connected columnist Walt Mossberg of the Wall Street Journal, who assured his readers that iPhones would eventually get Flash support, perhaps by the end of the year. By allowing media talkers to establish the idea among the public that what iOS really needed a native App Store, and that Flash was probably already in the works, Apple could minimize parallel criticisms that it also needed to support Adobe Flash and other common cross-platform runtimes such as Sun's Java.

Once it delivered its App Store, Apple was now positioned to focus its resources on its new, exclusive development platform for iOS. It was only after the App Store was firmly established that Jobs took the unusual step of articulating why Apple would not support Flash, notably in his 2010 public letter, "Thoughts on Flash." By that time, developers and major content producers were already mostly prepared to shift away from Flash to deliver native iOS content. Apple had even convinced Google to deliver its mostly Flash-based YouTube in a form suitable for iOS users.

Yet secondary "concerns" that Apple wouldn't be supporting Flash later prompted competitors to focus their efforts on supporting Flash as an exclusive, competitive edge over Apple's iPhone. Even Google picked up Flash and partnered with Adobe in a misguided, ultimately disastrous effort to dump resources into making Flash work on Android, rather than exclusively focusing on Android as a development platform itself.

This captivated Flash fans and gave Android enthusiasts the false hope that Flash would both remain critically important and a huge problem for Apple. Yet after spending significant resources to support Flash, Google found that it wasn't a good idea at all. It was then tasked with the work of removing it. This not only wasted Google's development resources, but prevented the company from pursuing more worthy efforts.

Apple didn't directly fool Google. It merely ignored media chatter while Google worked to gain attention for itself by listening to what "the public was demanding," even though this was just pundits demanding a faster horse rather than a modern mobile car. And it largely came in response to marketing by Adobe pushing the idea that the Flash horse that it was trying to sell was fast enough and that nobody needed a car.

Apple's pattern of secrecy

All these years later, Apple continues to do the same thing over and over, incrementally releasing elements of its overall strategy according to a plan, with the objective of maintaining perpetual consumer anticipation and ultimately deliver surprises when they are ready to do so. Apple typically doesn't care that outsiders are often wrong about its plans, and only bothers to issue a correction when what they're saying verges into purely false comments that have some material impact beyond just being incorrect.

Notable examples include Apple taking issue with "the Big Hack," an unsubstantiated and unbelievable story made up by Bloomberg, and briefly dismissing as "absurd" the bizarre piece from the Wall Street Journal portraying fictions about Jony Ives and how Apple does design. But these media engagements are rare.

When Apple released Apple Watch, it focused on the material benefits it offered. Pundits rallied around the idea promoted by Google that a smartwatch should be round. Five years later, Google, Samsung, and various other watchmakers have desperately tried to make round smartwatches a thing the same way they tried to make Flash important. Apple has instead focused on valuable features, unveiling hardware capable of performing an EKG and alerting users of irregular heart activity. Apple Watch is regularly in the news for saving lives. Tons of round smartwatches exist, but continue to fail to gain attention because they offer little of value.

Similarly, Apple set up the introduction of AirPods in conjunction with iPhone 7, removing its headphone jack to focus on the freedom of wireless earbuds. Google, Samsung, and their enthusiasts worked Flash-like on making the removal of the analog headphone jack a terrible and viciously user-hostile problem. All these years later, AirPods have become a global hit and nobody of consequence was materially dissuaded from buying an iPhone. Most modern Androids have since given up on making the headphone jack an important feature.

Apple started off 2019 with a focus on the new Services it would be introducing throughout the year, and new partnerships it would use to do this, specifically with its iTunes App. While the media largely tried to reframe this as a huge failure for Apple hardware and an embarrassing, desperate concession to Samsung, Amazon, Roku, and others, that dumb take offered just enough distraction to enable Apple to later sneak out the full launch of its new TV app and a comprehensive strategy for al la carte subscription Channels along with AirPlay 2 streaming and support for a limited number of initial cable partners, in addition to limited iTunes Movies and Apple TV+ availability on third party hardware— without giving competitors the time to issue their own copies.

At WWDC it introduced more about its plans for the year, introducing new platform technologies to bring iPad apps to Macs and ways to accelerate and improve the co-development of titles across iOS, iPads, Apple TV and Macs with Swift UI. Both of these seemed highly relevant to the development of Apple Arcade, which the company had introduced in March without offering a full set of details on how it would work. This progressive reveal wasn't an accident and didn't occur without a plan.

Yet again, the media was given just enough information to issue a distracting cloud of nonsense that suggested that maybe Apple was giving up on native Mac development and planning to turn its desktop platform in the little more than an expensive way to run iOS applets. After all, it was giving up on Apple TV to bring iTunes to Roku, right?

By allowing media chatters to blow out a smokescreen of nonsense based upon the ongoing assumption that Apple is doomed and teetering on the brink of failure, Apple can set up and deliver surprises that dramatically rise above the smoke and ultimately impress users just as its products are ready to sell.

Fully detailed failures

Contrast this with the very early announcements commonly made by Microsoft, Samsung, Huawei and Google for products that are not yet finished. These are hyped into the stratosphere by giddy media supporters only to set up equally dramatic levels of disappointment when they don't materialize. Google Glass, Microsoft Hololens, Samsung Fold, and Huawei's supposedly "ready to go" Android alternative were all blown up as important milestones in the history of tech before being revealed as little more than back-burner exercises that were not really going to make any significant commercial or strategic impact on the tech world at all.

Google's Pixel C tablet and then its Pixel phones with a some unique camera software features and the wildly overhyped Pixel Visual Core silicon have similarly not even mattered in the slightest, despite years of screaming punditry and comments-section fans bellowing out how important and incredible and amazing it was that Google was making such impressive progress in hardware while Apple was struggling to understand services. Yet today, Pixel is a turd sandwich while Apple's Services are generating over $10 billion in revenues every quarter.

The same can be said of the decade of obeisance paid to Microsoft's Surface group by the media. This desperate fawning started with Windows Surface RT and stretched along into various form factors of PCs given modern styling and fancy branding and marketing by Microsoft at the cost of billions of dollars.

A decade later, Surface has done little more than hobble along as a 1 million unit per quarter hobby that has done little to attract new attention or relevance to Windows as a platform or prop up the struggling PC industry overall. Apple sells more Watches. Apple sells more Apple TVs. It appears Apple sells about as many HomePods.

Collectively, Android and Windows licensees have similarly laid out all their secrets far in advance and struggled to create hype for their initiatives, even as Apple is mocked and derided as having all sorts of problems based on the limited understanding of where it is going by the media and other observers. And yet at every Apple Event, the company reveals new secrets and surprises that create hype and anticipation for its products right as they are ready to sell.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Bon Adamson

Bon Adamson

-m.jpg)

12 Comments

IMHO, one of the reasons why Apple events are not as impactful as before is the supply chain is longer than it used to be. That makes for a greater availability of new products, but also creates a larger risk of that product being prematurely shown, or plans stolen to have another factory make knock off or counterfeit parts.

Apple has realized that the iPhone is not its cash cow anymore and has been diversifying its resources into updating neglected products like iPads and Macs.

Apple now has to deal with apathy from the general consumer who refuses to spend 1k on a smartphone and potential tariffs that can eat away profits on a device that needs to make back the money spent on R&D.

People whose lives revolve around eating and going to the bathroom have a difficult time understanding the forward thinking of Apple.

While I think the article is generally true and accurate, I take exception to the implication in the first paragraph that the apps and the app store ARE the ecosystem.

I think instead that the apps and app store are part of the ecosystem, but the ecosystem is far more than that.

I think the ecosystem is also:

-- Apple's integration of hardware and software that enhance each of its products

-- The integration of its various products that makes each product better than it could ever be by itself.

-- Apple's reputation for dependability and reliability -- including, but not limited to its support system

-- Apple's reputation for security and privacy

-- Apple's reputation as a market leader who makes great products that people can enjoy and trust.

-- And more...

Well analysis. Almost a decade following Apple’s events, I believe much of what’s written is true. Apple has been years ahead internally while it only reveals as much as necessary when whatever they have planned is ready for public appearance.

I think this is a big part of what Steve Jobs had learnt at Pixar and brought with him back to Apple and building it into what is now commonly known as Apple’s DNA.