Editorial: Steve Jobs shared secrets of Apple's iPad but nobody listened

Last updated

Before he passed away, Steve Jobs uncharacteristically shared some strategic insights in public on what would make tablets successful. Rather than the rest of the industry benefiting from his observations, critics and competitors insisted he was wrong and set out to prove it.

Steve Jobs didn't just unveil the iPad as a new product in 2010. He talked at length during the media event, providing a deep look into Apple's strategic thinking on the subject of tablets. It was as if Jobs were giving the industry a Xerox PARC style tour of the secret labs inside Apple. He not only revealed the next big thing that would radically change the computing landscape but also detailed exactly what was going to make it commercially successful.

To compete for relevance and fill a valuable niche between a regular PC and a phone, Jobs said iPad would need to be much simpler to use than a PC. And to stand apart as useful next to a smartphone, it would be critical to have tablet-optimized mobile apps that were more sophisticated than a phone. These ideas may seem obvious today, but were once opposed and defied by competitors and critics.

In effect Jobs had detailed the exact x:y coordinates of the sweet spot for selling tablets to consumers. Why didn't anyone listen? In part, it was because copying Apple strategy would require enormous amounts of work and required product development skills its competitors didn't have.

Creating a super simple tablet was not super simple

Jobs' hardware vision for iPad was a tablet that was virtually nothing but a large graphical display. But that meant that the display and the GPU driving its graphics would both have to be outstanding. In 2010, nobody else had access to cost-effective displays and high-performance mobile GPU silicon and, critically, the goodwill of a virtually guaranteed audience of millions of buyers, if the price were right.

Apple was selling leading volumes of high-quality MacBook screens and tens of millions of smaller mobile devices. It planned to custom-develop iPad's A4 chip specifically to deliver competitive mobile graphics, splitting its development expense between iPad and the new iPhone 4 featuring a Retina Display— which Apple knew it could sell in the tens of millions. Apple ended up selling 15 million iPads across its first 9 months of sales.

All of Microsoft's Tablet PC partners combined hadn't sold 15 million tablets over ten years of trying. But they were also trying to sell Bill Gates' vision of a tablet being a full PC with some additional mobility features that often ended up far more expensive than a regular PC.

Samsung had equal access to the same A4/Hummingbird chip design as iPad and actually built most of the world's mobile screens, but even it couldn't match Apple in display size and price because iPad's $499 price was dependent upon Apple being able to sell millions. Samsung had been building thousands of Q1 Tablet PCs and other devices for years, and knew it wouldn't sell millions.

Even in its second year of cloning iPad, Samsung barely sold 1M Galaxy Tabs in the U.S., the largest market for tablets, and that figure involved tons of promotional giveaways. It doesn't appear that tablets ever really contributed to Samsung Mobile profitability, despite the ostensibly obvious advantage it had as the world's leading manufacturer of displays and other components.

Beyond just its hardware, Jobs' presentation made the iPad sound simplistic in operation, but this would be difficult to deliver and hard to defend against criticism. A tablet that was "super simple" enough to be differentiated from PCs would require a lot of thoughtful decisions on what could be "courageously" removed to make it capable of seeming fast while running on a lower-powered mobile chip.

These choices would have to stand up in the face of public opposition. Media critics didn't care about the technical details; they could just demand a brainstorm of features they recalled using on PCs without giving any thought to how these things would drive up costs and complexity and tear down performance.

Removing complexity while critics screamed about the tyranny of its omissions was something Apple had lots of experience with. From the Mac to iPod to iPhone, Apple had painstakingly created new, simpler devices that its competitors all rushed to turn into more complicated versions, partly because they didn't understand the value of simplicity, but primarily because delivering simplicity was more difficult work. And in tandem, simple-minded critics vilified simplicity and begged for sophisticated complexity, often without realizing how dangerously simple it would be to add toxic complexity.

Tablet-optimized apps would not come easy either

Good mobile apps are very expensive to create. The difficulty and risk of building apps for an unproven new platform has effectively killed most aspiring new devices before they could ever develop an audience capable of supporting third party development.

By 2010, there appeared to be perhaps three platforms that could transition to tablets and bring their existing apps with them: iOS, Android and Windows. But this wouldn't be enough, Jobs noted. A successful tablet needed to be better, and that would mean it would need new, custom-built apps specifically optimized to work well on a tablet.

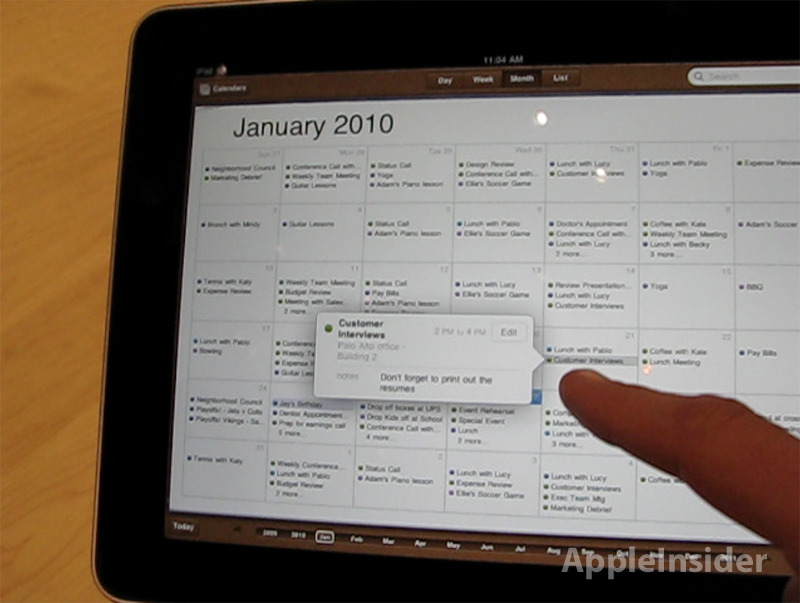

Jobs showed off a full suite of Apple's own bundled apps optimized for iPad, as well as its new Keynote, Pages and Numbers, demonstrating how clearly more valuable a tablet could be with iPhones' multitouch gestures expanded upon to take full advantage the larger display. He didn't reveal how much Apple spent to develop those apps— millions of dollars on top of the opportunity cost of investing the software expertise of teams of the best people Apple could find.

iPad did benefit tremendously from iPhone's App Store having already gotten off to a good start. But developers also faced the problem of trying to sell iPad-specific apps to customers who had already bought the app on their phone. Users expected great tablet apps but didn't expect to have to pay for them. Apple identified these issues and worked to actively help developers hash out the right strategy for their apps. Its tablet competitors largely didn't and expected that third party app issues would just work out on their own.

Apple also faced competitive pressures from developers that didn't particularly want the iPad to survive, and certainly didn't want Apple to extend its iOS lead into tablets. Apple likely created its iWork apps first because it could be assured that Microsoft wouldn't port over Office. In fact, Microsoft's then-CEO Steve Ballmer actually held up the launch of its completed Office apps for iPad until 2014.

Facebook, already the leading mobile app, similarly refused to bring its app to iPad as part of a fight over control of user data that blew open in 2010. Facebook pulled out of its collaboration with Apple to integrate its social networking with iTunes Ping, resulting in a half-finished implementation that couldn't import "friends." It also refused to support Apple's iPhone social integration efforts until iOS 6, and held up even its HTML5 app for iPad for most of 2011 while exclusively launching a webOS version in hopes a spyware-friendly PC company would beat Apple in tablets.

Facebook only released a full screen web app for iPad at the end of 2011, and didn't ship a real native app for iPad until the summer of 2012. Facebook's chief executive Mark Zuckerberg later admitted that the company's mobile app strategy targeting HTML5 web apps as a lowest common denominator for reaching all mobile platforms had been a mistake that "burned two years" of its development efforts.

Google similarly was in no rush to deliver all of its apps for iPad. It didn't ship a native version of Calendar until 2017. The refusal of many big developers to support iPad opened up opportunities for smaller companies to build great, affordable mobile apps that delivered a surge of fresh innovation that attracted new buyers. In particular, enterprise users found entirely new uses for iPad due to its simplicity.

The age of three empires

A lot of Apple's insight into what would make or break the iPad came from its maturity as a company. That included its experience in building mobile devices and app platforms, but also its humbling failures from past mistakes: trying to invent the distant future, taking too long to complete a sellable product, lacking a clear use case for it, and failing to deliver new refinements at a regular clip.

By 2010, Apple had already established iPhone sales and the App Store was off to a tremendous start. iPad also benefited from Apple's decade-long experience with designing and mass-producing vast numbers of iPod mobile devices. Apple had a decade of experience in building macOS X and encouraging developers to build software for it. But it also had that decade of painful mistakes it made in the 1990s. Apple, Inc. was 34 years old and ambitiously— but cautiously— working to achieve its next big shot at greatness.

Neither Android nor Windows had built a solid mobile apps platform yet. Google and Microsoft also had no effective experience in building mobile devices on their own; their platforms delegated most tablet hardware engineering out to companies that had previously not been successful in creating new product categories.

In 2010, Google had just barely launched Android phones to commercial success with its first major carrier promotion on Verizon. Its Android Marketplace was a garbage bin of hobbyist experiments and shovelware with no curation. It had never previously maintained a consumer OS or app development platform, nor built a successful device business on its own.

But even more importantly, Google had never been allowed to taste failure. Fawning members of the media allowed it to throw out half-finished software as "beta" and looked the other way when it acquired companies that it took nowhere, or launched a new service and then pulled the plug after a year or two. Google had unchecked income from its birth and was protected from criticism like the rich 12-year-old company it was.

By 2010, Microsoft hadn't established a successful mobile apps platform despite years of trying. It had also failed to figure out any way of materially moving beyond the PC, despite many years of trying to launch handhelds, slates, watches, smart displays, music players, and various other concepts that never took off. Its only apparent hardware success had been Xbox, a product it could sell unprofitably and then use to earn back revenues by taxing its software developers' expensive game releases. That wasn't going to work with tablets.

Microsoft was Apple's corporate age, but rather than having a similar set of experiences, the company had achieved very little on its own. It was launched into profitability on a lucrative licensing deal for DOS, which it rode through the 1980s. Its greatest accomplishment in the 1990s was taking credit for the desktop computing model it copied from Apple. It then leveraged its DOS licensees to spread Windows at very little personal risk, and relied on silicon advances from Intel to make up for little real OS innovation of its own, amassing total market control by incrementally copying or buying up competitors the way Facebook does today.

What Microsoft did uniquely get right with DOS PCs, Windows, and Xbox was its strident efforts to support the third-party software developers on its platforms with good coding tools and the basic APIs they needed, not a bunch of grand APIs invented to usher in a Singularity. In the 1990s, Apple was the rich teenage company with bold idealism and plenty of money, and just getting its first taste of consequences.

How these platform companies approached competition with iPad reflected their corporate age and experience. Apple was duplicating what had worked for it before, while learning from its mistakes. Google would waltz in with the arrogant bravado of rich but inexperienced teen and fail spectacularly. Microsoft had a mid-life crisis where it forgot what had made it successful while trying to pretend to be the creative designer it never was, cranking out rewarmed copies of its past work that left it looking inauthentic and unqualified in mobile devices.

Tablets had never found a job to do before

When Jobs articulated Apple's vision for what would make a tablet device successful it was not what people were expecting. To virtually everyone, the natural progression of mobile devices needed to move smartphones closer to being a conventional PC, or alternatively, to scale the PC down towards handheld mobility. Most Apple fans specifically wanted to see a thin tablet-sized Mac with a touch screen.

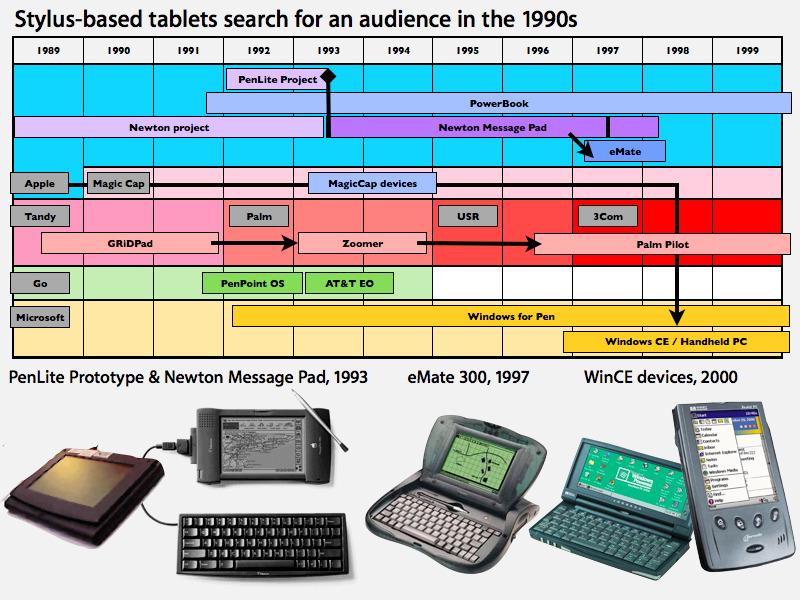

These concepts were not new. Back in the late 80s, Apple had experimented with a PenLite tablet Mac that was effectively just a screen with a pen. That design was far too expensive to build, forcing Apple to scale its mobile ideas down into a notepad it could sell for less than $2000. Newton was still too expensive, finally giving way to the $300 Palm Pilot that was more successful despite being far simpler. Almost magically, across many attempts at tablets, it turned out that the more complexity was stripped away, the more valuable and useful a tablet device became.

Still missing, however, was the clear idea of what, exactly, a simple tablet should be able to do. Various companies were playing with the idea of a tablet being little more than a web browser, such as Nokia's Linux-based Internet Tablet. Others were effectively a small TV. The most successful tablet-like product had been Sony Playstation Portable, released a couple of years before the iPhone and relying on physical media to deliver its games. Despite the backing of Sony and the killer app of video games, it still took two years to reach sales of 10M units, and that was at a $250 price.

Microsoft had spent decades trying to deliver Pen Computing and then Handheld PCs and then Tablet PCs, regularly making a new attempt every few years to deliver another version of the full complexity of a Windows PC paired with various mobile drawbacks that resulted in something worse— and usually more expensive— than a conventional laptop. At its pinnacle of trying, Microsoft actually announced that its latest attempt at the mobile PC involved "no compromises," as if they'd forgotten they were engineers altogether and were now just preaching a Windows gospel to excite their technology base into an emotional frenzy without any difficult, rational choices involved.

Jobs had never found a tablet to do before

Between Apple, NeXT, and Pixar, Jobs had a connection to an incredible range of advanced technologies throughout his life, but he never seemed to intersect with consumer tablets. He had missed the era of "Knowledge Navigator," Magic Cap, and Newton at Apple in the late 80s; at NeXT he hadn't ever publicly developed a tablet; and he didn't seem too interested in Tablet PC. One of his first axes to swing after returning to Apple in 2007 hit the Newton and eMate. Apple had already spun the products off into a subsidiary that was functioning independently. Jobs pulled it back into Apple and then shut it down.

That helped launch the provocative media narrative that claimed Jobs hated tablets because of a petty grudge, perhaps as much as he supposedly hated video games and TV. So when rumors began to swirl that Apple was working on a new tablet, there was pent-up excitement that something great was coming. But for some reason, it was widely imagined that Jobs was going to do something exactly like all the tablet projects he'd previously never had anything to do with and that had all gone nowhere.

Instead of repeating the same approach and expecting a different result, in 2010 Jobs held up what looked like a "big iPod touch." It sure didn't look much like any previous tablet concept.

The small iPod touch: iPhone apps without the phone

Alongside iPhone, Apple was selling iPod touch, a nearly identical-sized device that was missing phone features but ran the same apps. It could almost be considered a tablet, but it was really a Trojan horse. Its primary function was to show people who used a basic feature phone what a great mobile operating environment they could have right on their phone if they switched to an iPhone. Jobs referred to the $299 iPod touch as "training wheels for iPhone."

If iPod touch had been larger than the iPhone, it wouldn't serve this purpose as well. As a thin iPhone placeholder, it converted over legions of Nokia feature phone users. It even caught the attention of Nokia executives before iPhone did, because it clearly showed that the credible threat that Apple posed wasn't its phone technology but rather came in the form of its simple mobile platform for powerful native apps. This was clearly going to destroy Nokia's Internet Tablet business and then siphon off its phone handset customers, all by virtue of its iTunes-simple apps teaching the installed base of iPod users how to use an iPhone.

In fact, by 2010 the only success occurring outside of iOS was Google's identical app platform for Android, which had shifted from being a simple Java button phone to being a direct copy of Apple's new iPhone apps platform from the very first moment that Google saw what Apple had been working on. Google failed to similarly clone Apple's iPad however.

iPad, a phone, and a Mac...are you getting it? These are three separate devices!

Apple could have just quietly started selling the iPad in its retail stores to see who would buy it. Instead, Jobs called the media to an event and outlined exactly why a tablet needed to be iPhone-level simple rather than Macintosh-level sophisticated. It would be the opposite of an iPod touch, selling itself as a new, differentiated product rather than acting as an entry-level catalyst to attract new iPhone buyers.

At the time, for many, it was a surprise— and then disappointment— that Apple was defining iPad as a simple apps platform like iPhone rather than the lighter, thinner Macintosh that virtually everyone was expecting. But the best way a tablet could offer a real advantage over a PC, Jobs explained, would come from being effortlessly simple. That would be appreciated by consumers so much that they'd pay for that in preference to a complicated PC experience slimmed down a bit. There was no barrier to "switch," they could just pick up an iPad and instantly use it, casually, without finding a teenager to set it up for them.

Jobs demonstrated how effortlessly easy the iPad was to start using, to figure out, and to navigate by touch. That meant no handwriting recognition and no pen-oriented computer interface, no having to configure tons of settings, no sets of configurable ribbons of toolbars to learn, and no exposure to the low-level technical details of the OS. Jobs didn't apologize for not having a mouse. Instead, he stated in an official press release, "iPad is our most advanced technology in a magical and revolutionary device at an unbelievable price."

A few months later, Jobs detailed another detail about the iPad: no support for Adobe Flash. This would ensure it didn't inherit the worst things about PCs, while also supporting the idea that iPad needed custom, tablet-optimized apps not just the ability to "sort of" use apps created for a different platform.

Google's PC people thought people wanted PCs

When Jobs described iPad as a "Post PC" device, critics scoffed that it was really "just a big iPod touch," to imply that a larger device should be more sophisticated and complex. The idea was that nobody would want Apple's super simple tablet for long, because everyone wanted a full PC in a handheld device, with pretty much everything but an optical drive and that might even come in hand sometimes.

After copying the iPhone, Google wanted to prove that it wasn't just copying Apple's ideas and could come up with good product strategies on its own. It ultimately made a series of decisions that set Android's approach to tablets in direct conflict with Apple's, each with terrible consequences.

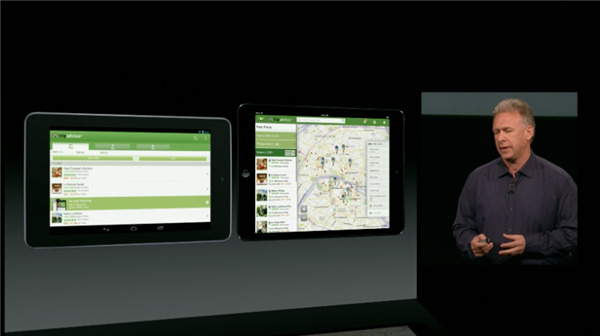

Google's first official response to iPad, a year late, was Android 3.0 Honeycomb, a release that debuted larger, widescreen tablet devices with more complexity and sophistication than Apple's simple iPad Home Screen with its grid of mobile apps. It appeared just ahead of iPad 2, Apple's more powerful but still effortlessly simple tablet running more, unique new tablet-optimized apps like GarageBand and iMovie.

Google's Honeycomb tablets featured more memory, higher resolution screens, and a new high-tech user interface called "holographic" that could play stacks of overlapping videos, with menus and widgets and a real file system. Android tablets were also more expensive. They were stretching up into the category of almost being a PC.

And that was the problem because when they inched up to the definition of a "real" PC in features, they couldn't quite measure up. Super fancy tablets still couldn't run regular PC software titles. And even if those titles were ported over natively, they'd still run slower than expected because tablets have to either pick a more efficient mobile-optimized chip that's much slower than a PC, or an almost as fast baby desktop chip that is going to destroy battery life, making it not very mobile for long.

While Honeycomb tablets were Google's first reaction to iPad, the company's original stab at the ultra-mobile PC market was even less imaginative. Chrome OS intended to replace the PC netbook with a Linux clamshell that could only run a web browser hosting web apps. Despite the simplicity, Google couldn't get Chromebooks to market until two years later, where they were now competing for attention with Honeycomb tablets as well as iPad. Google was doing twice the work of launching new ideas, but getting nothing for it because its ideas were so unimaginative and poorly implemented.

Android Honeycomb tablets and Chromebooks were both just an almost-PC experience. Even as CNET and the gadget blogs all gushed over how cool the Honeycomb slates like the "Xoom" were, there was a distinct lack of interest from the public. All of those models flopped right out of the gate.

Simple was correct

Apple's iPad wasn't trying to compete with Macs or convert Mac users over to iPad. It was exploring different use cases, and trying to appeal to a new audience of people who didn't want to manage a PC. iPad was aimed to be useful in places where a conventional PC is too much. That required delivering simplicity and new tablet-optimized apps that would not be directly compared to a PC.

The industry largely imagined that Apple should immediately start pushing iPad upward into its own existing Mac territory, rather than exploiting entirely new opportunities. This was ignorant because the desktop PC market was growing saturated. Over the next four years, Mac sales hovered between 16-18M units per year while iPad rocketed up into the orbit of 70M units. All these years later, Apple's Mac sales to people who wanted the full PC experience have only grown incrementally above 18M, but iPad sales exploded and then settled down into a sold new business with over twice the units and roughly the same revenues as its Mac business.

HP, Lenovo, Dell, and other PC makers didn't create a separate new tablet business that was as large as their PC sales. They watched as PC sales stopped growing, as their Windows and Android tablets lingered at low levels of interest, and as iPad ate into their PC sales while inventing new Post-PC markets around them.

A big part of why: iPad was designed to be simple enough to hand to a child, or to operate while intoxicated. That's what made it different, and better at some things, and therefore worth paying perhaps even a slight premium for. Jobs was right: people who wanted a PC should still buy a PC, but what people found valuable in a tablet was its simpler, more relaxed experience with games, or artwork, or browsing news, or showing off data to clients on a dead-simple device.

Stretched out phone apps are not tablet optimized

Just as big Honeycomb tablets were inching too close to being a PC to avoid comparison, Google's subsequent Nexus 7, Samsung's Galaxy Tab 7, and similar form factors like the Blackberry Playbook were getting too close to a phone to seem independently valuable. Those tablets were more like a big phone that couldn't work as a phone. They were literally a "big iPod touch," but they were arriving too late to convert any feature phone users.

At the end of 2010, Jobs answered an analyst question discussing all the new tablets entering the market, saying there were really "only a handful of credible entrants," but that "they use 7 inch screens," which he said "isn't sufficient to create great tablet apps."

Jobs stated "we think the 7 inch tablets will be dead on arrival, and manufacturers will realize they're too small and abandon them next year. They'll then increase the size, abandoning the customers and developers who bought into the smaller format."

Burned by the searing lack of interest it had received for its Android 3.0 Honeycomb tablets in 2011, and then burned again by the continued interest in Apple's fancier but still ultra-simple, Flash-free, premium Retina Display iPad 3 that could run more new native tablet apps than any Android tablet, Google defied Jobs' warnings again as its changed its direction. It backed away from expensive Honeycomb tablets and led its Android licensees on a new race to the bottom in the summer of 2012 with a 7-inch tablet that was sized to watch movies and web videos and run stretched smartphone apps and games.

Google's Tegra 3-powered Nexus 7 tablet made various sacrifices to reach an incredibly low target price of $199, resulting in a severely flawed product with serious software defects that weren't addressed until a year after the product shipped. After two long years of trying to sell versions of the 7-inch Nexus 7, Google again shifted gears to build Nexus 9, a device nearly identical to Apple's iPad— just as Jobs had predicted.

A major reason for Android tablet failure was that Google wasn't working to deliver a tablet-optimized app experience. As Android phones grew larger, the value of small tablets began to evaporate. But larger tablets running Android were still only able to display mostly stretched-out phone apps.

iPad mini wasn't a 7 inch phone

At the end of 2012, Apple burned Google one more time by shipping its own smaller iPad mini, once again to incredible success. However, rather than being a 7-inch tweener-sized panel, iPad mini delivered a scaled-down experience of the standard iPad, running the exact same tablet-optimized apps.

Unable to sell many full-sized tablets, Samsung began offering a larger Note phablet at the end of 2011. That new hybrid product clouded the boundary between phone apps and tablet apps, further discouraging any new tablet-optimized apps, while also inching close to being an "almost PC" by involving a stylus and creating a more complex interface.

When Apple later launched its own larger phones starting in 2014, demand for smaller iPads also began to dramatically scale back. But Apple continued to sell full-sized iPads and eventually could expand its product line to deliver iPad Pro models capable of running even more sophisticated, tablet-optimized apps within the same simple environment.

Jobs' anticipation of what would be successful in tablets ended up being presciently correct. Having a clear, confident, strategic vision allowed Apple to make long term plans, which included developing custom silicon optimized specifically to competently deliver that vision.

In particular, Apple could build iPad mini with the previous year's A5 chips and have a fully differentiated set of tablets to offer, scaling from a lower-priced small tablet with a regular screen to its best A6X-powered full-sized Retina Display iPad 4.

Apple's apps vs. the web

When Jobs launched the first iPhone he said the solution for third party software titles was going to be web apps. Developers pushed back hard. Not having access to the new iPhone's "Cocoa touch" native app APIs would mean their apps couldn't be nearly as good as the ones Apple was building.

Apple pretty clearly already had an App Store in development. The company was already selling mini-games for iPod, using certificate-signing to prevent malware tampering and software piracy. Jobs admitted Apple was working on an iPhone App Store that fall and unveiled its plans in detail the next spring. It quickly became abundantly clear that simple, native apps were a critically important part of the iPhone's success.

This makes it particularly dumb that just a few years later, the development community was again reversing things to claim Apple was now against web apps— including the entire Adobe Flash platform— in iOS and directing people to the App Store as the best way to distribute software as part of a nefarious act that was bad for everyone else.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

39 Comments

It's amazing that nearly a decade later and no one has been able to catch up. While it's not my preferred choice for a personal computer (I'm mostly on my MBP), it's certainly one of the most impressive.

Does Elizabeth Warren understand and know this history? She wants to go after Apple on the App Store and other tech companies. Apple almost went bankrupt in the mid- to late 1990s. Politicians that go after risk taking entrepreneurs who have become wealthy after almost losing everything, should be ejected from the political system. Did Elizabeth Warren ever start her own company? Does she viscerally understand what it takes to be an entrepreneur?

At the time I preferred the iPad instead of firing up my desktop or laptop. Because the iPad was 'instant-on'. But with todays laptops with SSD instead of a slow HDD I don't use the iPad anymore. A MacBook is so much easier because I don't have to hold it up. That could be a reason for the declining or should I say plateauing in iPad sales.

One of DED's favorite forms of storytelling is rewriting history to make Apple and Jobs seem to have thought of everything, but let's remember that we don't write articles about flops. You never see DED defending the genius of Ping, the iTunes social network, or the Apple HiFi. Still, there are lots of things in this article that qualify as spin, or that are just plain false. 1) When the iPad came out, people were stunned that it was just a scaled up phone that couldn't make phone calls, and not a more capable device. They were correct about its early limitations. 2) The product name almost sunk the launch, with people comparing it to feminine hygiene products. 3) The predicted dominance of the eBook and magazine industry never came to pass. 4) Jobs totally missed the importance of the App Store and 3rd party apps, which came later, and really had much to do with the success of the device. 5) Job's insistence that a stylus and keyboard were unnecessary have since been reversed, so which is it? Is Apple on the wrong track today, or did Jobs get it wrong in the beginning? 6) The iPad push into the K12 classroom as a textbook replacement is over. Schools are replacing aging iPads with Chromebooks that cost less, are more rugged, easier to manage, and simply do more. 7) The one big thing Apple got right was to make the iPad the best tablet money can buy, and to keep making incremental improvements. Staying above the low-end competition is what Apple always does, but it paid off because the low end Android and Amazon tablets are clunky, sluggish, and non-intuitive in comparison.